| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2009 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

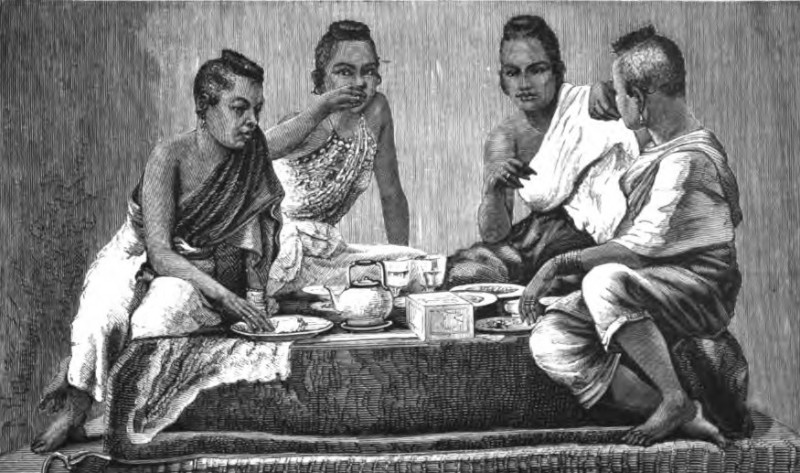

CHAPTER XIX.

THE PRINCESS SUNARTHA VISMITA AN hour after dark I again sought the good and tender-hearted Thieng, who not only hurried me off, telling me in a voice of great exultation that the physician's report had in a great measure ameliorated the rigorous confinement to which the royal prisoner had hitherto been subjected, but bravely sent two of her women to tell the Amazons to show me the apartment to which the sick princess had been removed. The small apartment into which I was ushered was dimly lighted by a wick burning in an earthen vessel. The only window was thrown wide open. Immediately beneath it, on a pair of wooden trucks which supported a narrow plank, covered with a flowered mat and satin pillow, lay the wasted form of the Princess Sunartha Vismita. Her dress was that of a Laotian lady of high rank. It consisted of a scarlet silk skirt falling in firm folds to her feet, a black, flowered silk vest, and a long veil or scarf of Indian gauze thrown across her shoulders; some rings of great value and beauty and a heavy gold chain were her only ornaments. Her hair was combed smoothly back, bound in a massive knot behind, and confined by a perfect tiara of diamond-headed pins. She was not beautiful; but when you looked at her you never thought of her features, for the defiant and heroic pride that flashed from her large, dark, melancholy eyes fixed your attention. It was a face never to be forgotten. At her feet were two other truckle-beds; on these were seated the two young Laotian women who shared her captivity, and who looked very wan and sad.  LADIES OF THE ROYAL HAREM AT DINNER Advancing unannounced close to this mournful group, I sat down near them, while the dark, depressing influence of the place stole upon my spirits and filled me with the same dismal gloom. The princess, who had been gazing at the little bit of sky, of which she could only get a glimpse through the iron ban of the open window, turned upon me the same quiet, self-absorbed look, manifesting neither surprise nor displeasure at seeing me enter her apartment It was a look that spoke of utter hopelessness of ever being extricated from that forlorn place, and a quiet conviction that she was very ill, perhaps dying, yet without a trace of fear or anxiety. The air was heavy and difficult to breathe, and for a moment or two I was silent, confounded by the unexpected bravery and fortitude evinced by the prisoner. But, quickly recovering my self-possession, I inquired about her health. "I am well," said the lady, with a proud and indifferent manner. "Pray, why have you come here?" With a sense of infinite relief I told her that my visit was a private one to herself. "Is that the truth?" she inquired, looking rather at her women for some confirmation than at me for a reply. "It is indeed,"] answered, unhesitatingly; "I have come to you as one woman would come to another who is in trouble." "But how may that he?" she rejoined, haughtily. "You must know, madam, that all women are not alike; some are horn princesses, and some are born slaves." She pronounced these words very slowly , and in the court language of the Siamese. "Yes, we are not all alike, dear lady," I replied, gently; "I have not come here out of mere idle curiosity, but because I could not refuse your foster-sister May-Peâh's request to do you a service." "What did you say?" cried the lady, joyfully rising, and drawing me towards her, putting her arms ever so lovingly round my neck, and laying her burning cheek against mine. "Did you say May-Peâh, May-Peâh?" Without another word, for I could not speak, I was so much moved, I drew out of my pocket the mysterious letter, and put it into her hands. I wish I could see again such a look of surprise and joy as that which illuminated her proud face. So rapid was the change from despair to gladness, that she seemed for the moment supremely beautiful. Her lips trembled, and tears filled her eyes, as with a nervous movement she tore open the velvet covering and leaned towards the earthen lamp to read her precious letter. I could not doubt that she had a tender heart, for there was a beautiful flush on her wan face, which was every now and then faintly perceptible in the nickering lamplight. A smile half of triumph and half of sadness curved her fine lip as she finished the letter and turned to communicate its contents to her eager companions in a language unknown to me. After this the three women talked together long and anxiously, the two attendants urging their mistress to do something to which apparently she would not consent, for at last she threw the letter away angrily, and covered her face with her hands, as if unable to resist their arguments. The elder of the women quietly took up the letter and read it several times aloud to her companion. She then opened a betel-box and drew out of it an inkhorn, a small reed, and long roll of yellow paper, on which she began a lengthy and labored epistle, now and then rubbing out the words she had written with her finger, and commencing afresh with renewed vigor. When the letter was finished, I never in my life saw a more unsightly, blotted affair than it was, and I fell to wondering if any mortal on earth would have skill and ingenuity enough to decipher its meaning. But she folded it carefully, and put it into a lovely blue silk cover which she took from that self-same box, — which might have been Aladdin's wonderful lamp turned inside out, for aught I knew to the contrary, — and, stitching up the bag or cover, she sewed on the outside a bit of paper addressed in the same mysterious and unknown letters, which bore a strong resemblance to the Birmese characters turned upside down, and were altogether as weird and hieroglyphic as the ancient characters found in the Pahlavi and Deri manuscript. When all her labors were completed, she handed it to me with a hopeful smile on her face. Meanwhile the princess, who seemed to have been plunged in a very profound and serious meditation, turned and addressed me with an air of mystery and doubt: "Did May-Peâh promise you any money?" On being answered in the negative, "Do you want any money?" she again inquired. "No, thank you," I replied. "Only tell me to whom I am to carry this letter, for I cannot read the address, and I'll endeavor to serve you to the best of my ability." When I had done speaking she seemed surprised and pleased, for she again put her arms round about my neck, and embraced me twice or thrice in the most affectionate manner, entreating me to believe that she would always be my grateful friend, and that she would always bless me in her thoughts, and enjoining me to deliver, the letter into no other hands but those of May-Peâh, or her brother, the Prince O'Dong Karmatha, who was concealed for the present, as she said, in the house of the Governor of Pak Lat. I returned her warm embraces, and went home somewhat happier; but I seemed to hear throughout the rest of the night the creaking of the huge prison door which had turned so reluctantly on its rusty hinges. |