|

Web and Book design, |

Click Here to return to |

|

Web and Book design, |

Click Here to return to |

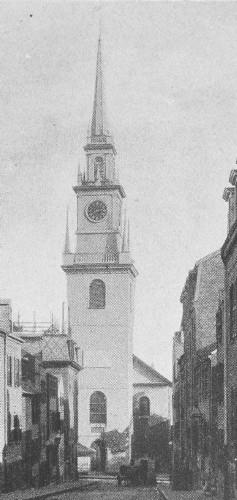

THE MESSAGE OF THE LANTERNS

THERE are many points of view from which this tale of Paul Revere may be told,

but to the generality of people the interest of the poem, and of the historical

event itself, will always centre around Christ Church, on Salem Street, in the

North End of Boston the church where the lanterns were hung out on the night

before the battles of Lexington and Concord. At nearly every hour of the day

some one may be seen in the now unfrequented street looking up at the edifice's

lofty spire with an expression full of reverence and satisfaction. There upon

solid masonry of the tower front, one reads upon a tablet:

THE SIGNAL LANTERNS OF

PAUL REVERE

DISPLAYED IN THE STEEPLE

OF THIS CHURCH, APRIL

18, 1775,

WARNED THE COUNTRY OF

THE MARCH OF THE

BRITISH TROOPS TO LEXINGTON

AND CONCORD.

CHRIST CHURCH, BOSTON, MASS.

PAUL REVERE HOUSE, BOSTON, MASS.

If the pilgrim wishes to get into the very spirit of old Christ Church and its

historical associations, he can even climb the tower

|

" By the wooden stairs, with stealthy tread,

To the belfry chamber overhead,

And startle the pigeons from their perch On the sombre rafters, that round him make

Masses and moving shapes of shade " |

to look down as

Captain John Pulling did that eventful night on

|

"The graves on the hill,

Lonely and spectral and sombre and still." |

The first time I

ever climbed the tower I confess that I was seized with an overpowering sense of

the weirdness and mystery of those same spectral graves, seen thus from above.

It was dark and gloomy going up the stairs, and if John Pulling had thought of

the prospect, rather than of his errand, I venture to say he must have been

frightened. for all his bravery, in that gloomy tower at midnight.

But, of course, his

mind was intent on the work he had to do, and on the signals which would tell

how the British were to proceed on their march to seize the rebel stores at

Concord. The signals agreed upon were two lanterns if the troops went by way of

water, one if they were to go by land. In Longfellow's story we learn that

Pulling

|

"Through alley and street,

Wanders and watches with eager ears,

Till in the silence around him he hears

The muster of men at the barrack door,

The sound of arms and the tramp of feet,

And the measured tread of the grenadiers,

Marching down to their boats on the shore." |

It had been decided

that the journey should be made by sea!

The Province of

Massachusetts, it must be understood, was at this time on the eve of open

revolt. It had formed an army, commissioned its officers, and promulgated orders

as if there were no

such person as

George III. It was collecting stores in anticipation of the moment when its army

should take the field. It had, moreover, given General Gage whom the king had

sent to Boston to put down the rebellion there to understand

that the first movement made by the royal

troops into the country would be considered as an act of hostility, and treated

as such. Gage had up to this time hesitated to act. At length his resolution to

strike a crippling blow, and, if possible, to do it without bloodshed, was

taken. Spies had informed him that the patriots' depot of ammunition was at

Concord, and he had determined to send a secret expedition to destroy those

stores. Meanwhile, however, the patriots were in great doubt as to the time when

the definite movement was to be made.

Fully appreciating the importance of secrecy, General Gage quietly got ready

eight hundred picked troops, which be meant to convey under cover of night

across the west Bay, and to land on the Cambridge side, thus baffling the

vigilance of the townspeople, and at the same time considerably

shortening the distance his troops would have to march. So much pains was taken

to keep the actual destination of these troops a profound secret, that even the

officer who was selected for the command only received an order notifying him to

hold himself in readiness.

"The guards in the town were doubled," writes Mr. Drake, "and in order to

intercept any couriers who might slip through them, at the proper moment mounted

patrols were sent out on the roads leading to Concord. Having done what he could

to prevent intelligence from reaching the country, and to keep the town quiet,

the British general gave his orders for the embarkation; and at between ten and

eleven of the night of April 18, the troops destined for this service were taken

across the bay in boats to the Cambridge side of the river. At this hour, Gage's

pickets were

guarding the deserted roads leading into the country, and up to this moment no

patriot courier had gone out."

Pulling with his

signals and Paul Revere an his swift horse were able, however, to baffle

successfully the plans of the British general. The redcoats had scarcely gotten

into their boats, when Dawes and Paul Revere started by different roads to warn

Hancock and Adams, and the people of the country-side, that the regulars were

out. Revere rode by way of Charlestown, and Dawes by the great highroad over the

Neck. Revere had hardly got clear of Charlestown when he discovered that he had

ridden headlong into the middle of the British patrol! Being the better mounted,

however, he soon distanced his pursuers, and entered Medford, shouting like mad,

"Up and arm! Up and arm! The regulars are out! The regulars are out!"

Longfellow has best described the awakening of the country-side:

|

"A hurry of hoofs in the village street,

A shape in the moonlight, a bulk in the dark,

And beneath, from the pebbles, in passing, a spark

Struck out by a steed flying fearless and fleet;

That was all! And yet, through the gloom and the light,

The fate of a nation was riding that night;

And the spark struck out by that steed, in its flight,

Kindled the land into flame with its heat." |

The

Porter house in Medford, at which Revere stopped long enough to rouse the

captain of the Guards, and warn him of the approach of the regulars, is now no

longer standing, but the Clark place, in Lexington, where the proscribed fellow

patriots, Hancock and Adams, were lodging that night, is still in a good state

of preservation.

The room occupied by "King" Hancock

and "Citizen" Adams is the one on the lower floor, at the left of the entrance.

Hancock was at this time visiting this particular house because "Dorothy Q," his

fiancιe, was just then a guest of the place, and martial pride, coupled,

perhaps, with the feeling that he must show himself in the presence of his

lady-love a soldier worthy of her favour, inclined him to show fight when he

heard from Revere that the regulars were expected. His widow related, in after

years, that it was with great difficulty that she and the colonel's aunt kept

him from facing the British on the day following the midnight ride. While the

bell in the green was sounding the alarm, Hancock was cleaning his sword and his

fusee, and putting his accoutrements in order. He is said to have been a trifle

of a dandy in his military garb, and his points, sword-knot, and lace, were

always of the newest fashion. Perhaps it was

the desire to show himself in all his war-paint that made him resist so long the

importunities of the ladies, and the urgency of other friends! The astute Adams,

it is recounted, was a little annoyed at his friend's obstinacy, and, clapping

him on the shoulder, exclaimed, as he looked significantly at the weapons, "That

is not our business; we belong to the cabinet."1

It was Adams who threw light on the whole situation. Half an hour after Revere

reached the house, the other express arrived, and the two rebel leaders, being

now fully convinced that it was Concord which was the threatened point, hurried

the messengers on to the next town, after allowing them barely time to swallow a

few mouthfuls

of food. Adams did not believe that Gage would send an army merely to take two

men prisoners. To him, the true object of the expedition was very clear. Revere,

Dawes, and young Doctor Prescott, of Concord, who had joined them, had got over

half the distance to the next town, when, at a sudden turning, they came upon

the second redcoat patrol. Prescott leaped his horse over the roadside wall, and

so escaped across the fields to Concord. Revere and Dawes, at the point of the

pistol, gave themselves up. Their business on the road at that hour was demanded

by the officer, who was told in return to listen. Then, through the still

morning air, the distant booming of the alarm bell's peal on peal was borne to

their ears.

It was the British

who were now uneasy. Ordering the prisoners to follow them, the troop rode off

at a gallop toward Lexington, and when they

were at the edge of the village, Revere was told to dismount, and was left to

shift for himself. He then ran as fast as his legs could carry him across the

pastures back to the Clark parsonage, to report his misadventure, while the

patrol galloped off toward Boston to announce theirs. But by this time, the

Minute Men of Lexington had rallied to oppose the march of the troops. Thanks to

the intrepidity of Paul Revere, the North End coppersmith, the redcoats, instead

of surprising the rebels in their beds, found them marshalled on Lexington

Green, and at Concord Bridge, in front, flank, and rear, armed and ready to

dispute their march to the bitter end.

|

"You

know the rest. In the books you

have read

How the British regulars fired and fled

How the farmers gave them ball for ball,

From behind each fence and farmyard wall,

Chasing the redcoats down the lane,

Then crossing the fields to emerge again

Under the trees at the turn of the road,

And only pausing to fire and load.

"So through the night rode Paul Revere;

And so through the night went his cry of alarm

To every Middlesex village and farm

A cry of defiance and not of fear,

A voice in the darkness, a knock at the door,

And a word that shall echo for evermore!

For, borne on the night wind of the past,

Through all our history, to the last,

The people will waken and listen to hear

The hurrying hoof beats of that steed,

And the midnight message of Paul Revere." 2 |

NOTE.

Mr. W. B. Clarke, of Boston, has called the writer's attention to a pamphlet

entitled:

"PAUL

REVERE'S SIGNAL.

The True Story of the Signal Lanterns in Christ Church, Boston. By the Rev.

John Lee Watson, D. D. New York, 1880."

which seems to offer convincing proof that Captain Pulling, Paul Revere's

intimate from boyhood, and not sexton Robert Newman, as is generally believed,

was the "friend" mentioned in Revere's journal, and performed the patriotic

office of hanging the lanterns.

1

Drake's "

Historic Fields and Mansions Of Middlesex."

Little, Brown & Co., publishers.

2

"Paul Revere's Ride:" Longfellow's Poems. Houghton, Mifflin & Co., publishers.