| Web

and Book design, |

Click

Here to return to |

|

CHAPTER II

THE

LIFE OF A BEAVER COLONY

IN the foregoing pages, the work done by the beaver has been described with more or less thoroughness. It has perhaps proved dull reading, but seemed necessary in order that the habits of the animal should be more fully understood, and his tasks more completely appreciated. We shall now see something of the life of these busy creatures, and the best way will be to follow them through several consecutive years, seeing how they live, and plan, and work together. We will imagine that it is spring, the dreary, monotonous winter has passed. The sun is warming the earth and awakening the plant world to life and activity, the rich mosses of the northern woods are becoming more green and beautiful, and the flowers are unfolding their petals to brighten the country and tempt the drowsy insects from their long sleep. Everywhere the creamy white flowers of the bunchberry are strewn like snow over the woodland ground. Everything is awake and happy. The beaver who have no young are leaving their dark lodges, and seeking summer quarters, for before them lies a season of ease and happiness and good living.

Let us choose an imaginary beaver, a young male, and follow him on what presumably would be his life. He is two years old and he has his way to make in the beaver world. No longer may he remain beneath the parental roof, for that is taxed to the limit of its capacity, and as his brothers and sisters have had to go off into the wilds to shift for themselves, so also must he. Two summers ago he was a mere kitten, dependent on his parents, too small to work, and without much knowledge. But the time has not been wasted. He has seen what work is required by those who would thrive, and he has helped in all the various labours. He has seen how dams should be built, trees felled, lodges made and repaired. He has, in fact, served his apprenticeship, and is now but little below full size, while his strength is equal to any demands that may be made upon it. But he is alone, and therefore incomplete. A helpmate is necessary if he would live up to the traditions of the race and found a colony, so he starts off from the pond which for two years has been his home, his playground and the scene of his labour. At first it is lonely work exploring new country, following one stream after another. One day he comes to a pond held captive by a large dam and he enters it, and swims toward a lodge which is on a small island. There is no one at home, or sign of any of his kind about. In vain he examines the shores for indications. The builders of the dam are gone, and the wood pile near the house tells the sad story. It has scarcely been touched since with infinite labour the little colonists had collected it for their winter food; the winter they would never know, for the steel trap had come to those peaceful woods, and had accomplished its deadly work. Silently each night by the side of the dam had it closed its relentless jaws on the beaver that had come to repair the unexplained break in the well-built structure. Each night saw the colony dwindle in numbers, until of the nine, old and young, but one remained, too frightened to venture out by day or by night, for fear of meeting the fate of the other members of the family whose death she had several times witnessed. She had been powerless to assist. She had seen her father and mother, her brothers and sisters suddenly clutched by the foot and dragged under water. She had dived down to see what it meant, and had seen them struggling at the bottom, trying in vain to break free from the iron thing and the heavy chain which had slid down the inclined pole. A few frantic efforts and the end came. No more bubbles rose to the surface, all was quiet again and there was one less beaver in the world. Not understanding the constant repetition of the tragedy, she was simply seized with fear, and she kept away from the place which seemed to be the cause of so much misery. Even when she saw, by the lowering of the water in the burrow entrances, that the pond was going down, she still stayed at home, going out only under water to the wood pile and quickly returning to the lodge with a small twig for her meal. So she continued to live throughout the winter, escaping immediately the ice melted, and making her way among the patches of snow through the woods, but always following the course of the stream on which the pond had been made. She travelled slowly, sleeping during the day in holes in the banks. On her way she left signs here and there on conspicuous points of land. Small pieces of mud patted down and scented slightly with castoreum. Who shall explain her reason for doing this? Presumably it was meant as a means of communication with any other of her kind. If so it served its purpose, for the young male on finding the pond unoccupied, felt instinctively that there must be good reason for keeping clear of such an ill-omened place, and he slowly proceeded on his journey along the stream. For several days he continued on his leisurely way. At first there was no reason to hurry, but finally he came to one of the scented mud pats and became intensely interested. From it he learned that he was not alone. What more information he gathered from the inconspicuous pile of mud no one knows. But he too collected a small lump of mud and deposited it on the one he had found. Things looked different now. No longer did he dawdle along. He even threw caution to the winds and travelled by day, frequently finding fresher and fresher mud pats, until at last he overtook the maker of them. They met at night and beyond rubbing noses there was no formal introduction. They were both lonely and what more natural than that they should join forces to start out in life and travel together? The sealing of the life compact, which is seldom if ever broken by the beavers, was done without fuss or ceremony and was witnessed only by the moonlit trees. The next question was where they should go? Not back to the deserted pond, for even though it would have meant a great saving of work, the fact that it was known to men made it a dangerous place to live. Far better would it be to find some quiet stream which was free from all taint of their persistent enemy. The whole of Northern Canada lay before them, but they were slow travellers, their short legs prevented long marches. They dared not go far by land, it would be too dangerous, as they had no means of defence, and could not escape by running away from even the slowest of their enemies. In the water alone had they any chance of safety. There they were in their element, and nothing could touch them save the “fire stick” which belched forth its tiny, deadly missiles, and killed at such great distances. And so they followed the stream until it brought them to a large lake. For some weeks they stayed there, roaming about as the fancy seized them. The place offered great attractions to the house-hunting couple, and they were half inclined to settle there. They even went so far as to commence building a lodge on a small wooded point which jutted out into the water. The two outlets to the lake they saw could be easily dammed if necessary, so everything, including an unlimited supply of wood, suggested the advisability of making this their home. But one evening just as they had come out of a burrow near the foundations of their lodge, they were startled by a strange sound, human voices laughing and talking. Soon two queer objects came around the point of land, and the beavers saw two canoes; the graceful lines of the dark green canvas-covered craft did not appeal to them. What could they be? No such animals had they seen in all their travels, and so they lay immovable on the surface of the quiet water, and watched the canoes as they glided along. Closer and closer they came, when suddenly the air was tainted with the fearsome scent of man, that which above all things was most to be dreaded. Instinctively both of the silent watchers raised their tails and struck the water with a resounding smack which scattered the water high in the air, so that the countless drops reflecting the glorious colours of the setting sun resembled a golden shower. The beavers vanished beneath the disturbed water and sought safety in the dense tangle of brush with which the shore was lined, while the people in the canoe so suddenly startled by the noisy alarm signal stopped, surprised to hear from the guides that the terrific sound was made by beaver.

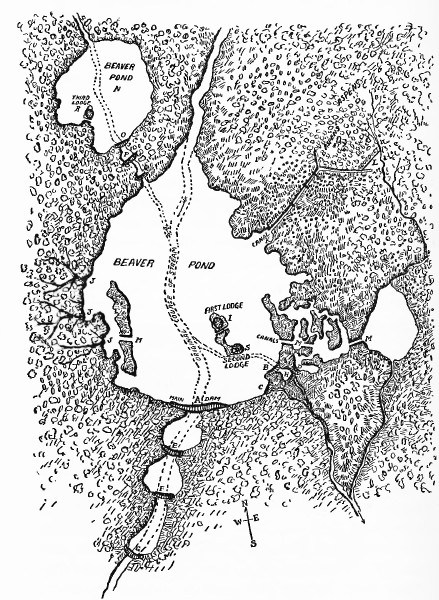

The party decided to camp near the place on chance of seeing something of the animals about which they had frequently heard so many remarkable stories. The guides, both of them being trappers, made notes for future use. Yes, they would come back in the proper season and get a few beaver skins from that lake. But the beavers thought differently. Their one idea now was to escape as rapidly as possible from a place which had proved to be known to man, and that night, while the camp fires crackled in front of the tents, and the sparks drifted lazily upward through the dark treetops to be lost among the countless stars, the beaver left their shelter, and under the cover of the kindly starlight made their way to the further end of the lake, where the outlet stream ran down through the woods. Along this rocky waterway they travelled, no word spoken, yet each filled with the one idea of putting as great a distance as possible between themselves and the human beings. For a mile or two they followed this stream without finding anything but rocks and steep banks. Occasionally they stopped to nibble some particularly enticing twig, or to listen cautiously for the possible approach of an enemy, but the woods were wrapped in the stillness of night and almost the only sounds were the murmuring of the brook as it glided among the moss-covered stone, purring as it went, and far away the hollow who-who-who-whoo of the owl. Once they got the tell-tale scent of a silent-footed lynx, so they hid in the water for over an hour, till the air was cleared of the invisible warning. Very early in the morning, when the sky was changing from the mysterious colour of night to the rosy hue which precedes the coming day, the beaver came to a little valley through which the stream flowed in a leisurely way. A tangle of alders marked a bog on one side and indicated the presence of a spring. On either side of the valley the sloping hills were well wooded with birches, poplars and maples, interspersed with spruces and pines. A little further along the stream divided into two branches, each finding its way from a different valley. The place attracted the beaver, but it was too near day for them to risk a careful and thorough investigation, so after making a hasty breakfast of roots and bark they sought the seclusion of an over-hanging bank where they could sleep comfortably and yet be near enough to the water to escape immediately if danger threatened. The day passed slowly and no sooner had the setting sun thrown the shadows of the tree-covered hill across the grassy valley, than the beavers came out to examine the surroundings, and see whether conditions were favourable for making a home. Apparently, everything was to their satisfaction. There were excellent sites for the two dams which would be necessary. Food was abundant, and from the appearance of the stream, they could count on an ample supply of water. They did not know that many years ago a small colony of beavers had lived there for several years, until a trapper had discovered their home and caught them all. That accounted for the grassy flat and for the division of the stream. In the many years which had passed since that tragedy the trees had grown again. As it was too early in the year to attempt much work the prospective house-builders contented themselves with making a deep burrow in the bank, with the two entrances well under water. There they lived for several weeks, when the stream began to dwindle in size as the hot weather dried up many of the smaller tributaries. Then it was advisable to commence work on the dams, and with this object in view they cut a number of alders and laid them lengthways with the banks and across the shallow stream. More and more were added, with clumps of sod and mud worked in on the upper side, so that the flow of water was retarded. At the end of a week, a small pond began to form. This grew larger as the dams were made more solid. At first the large one was not more than twenty-five feet in length, but the engineers decided that if they wanted a pond of sufficient size the length must be extended, and so they built on to the structures until they were nearly doubled in size, and the pond increased correspondingly. With the deepening of the water, the beaver found their burrows were no longer dry, so they decided that it was time to commence building a lodge. Summer was now at its height, and autumn would be upon them soon after the next moon. So even though it was full early, they chose the site for the new house. The place decided on was a small alder-covered knoll which the rising water had surrounded and made into an island. It was close to a spring, which was of great advantage. The earth being fairly soft a burrow was easily made. It started under water and ended in the centre of the islet. All roots were cut off and the tunnel made quite smooth, with a diameter of about thirteen inches. Very few of the growing alders were cut, as for the present they would be of service in supporting the building. Later they could be cut if necessary. These were busy nights for the little builders. Sticks of various sizes had to be cut and hauled up on the knoll; some of the wood they collected from among the dead branches which had been floated by the rising water, others they cut and from these they often eat the bark. This reduced the amount of work necessary, as the cuttings thus served two purposes. No big trees were cut at this time, that would come later. Among the network of sticks they placed great quantities of fibrous mud and sod, which was torn from the bottom of the stream close to their island. That again served a two-fold purpose; it made a deep place close to the house in which the winter food could be stored well below ice, and was the best of building material. The mud packed well among the woodwork, and the roots held it together and helped to prevent cracking. All this work was done with their hands, the clumps of sod being carried in their arms against the chin, and forced into position with the hands and nose. They did not follow the storybook method of patting it down with their tails. Very little mud was used in the centre of the lodge, as that was the ventilating flue.

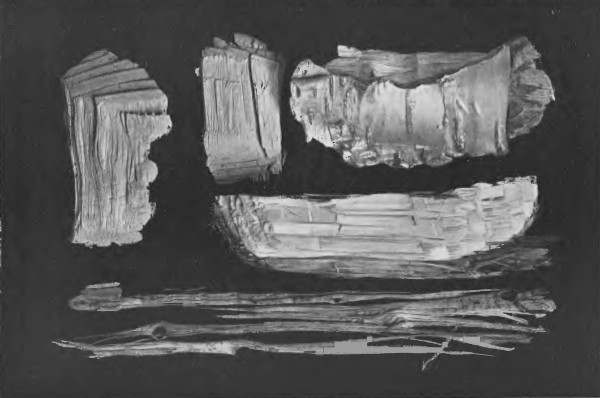

The woodwork was laid apparently in a very haphazard way, but always with the idea of making a rounded dome of tangled material which could not easily be torn apart. With surprising speed this grew, and within two weeks it had reached a height of over three feet and a maximum circumference at the base of about twenty feet. The inside in the meantime had been cut out over the land entrance of the tunnel, leaving a domed cavity twenty-three inches high and four feet across. Even in its rough condition, the lodge was quite suitable for a summer home, but as a precautionary measure, a second tunnel was made to enable the inmates to escape rapidly in case of emergency, and they never could tell at what moment an otter might make his way in. They are unwelcome visitors and are so quick and strong that the beavers, notwithstanding their powerful teeth, are usually unable to cope with them. In water they are the only four-footed enemy that beavers dread. On land everything is different, for apparently the land is not their natural habitat. Toward the end of August, the beavers were very comfortably settled, their pond was fully two hundred yards long and seventy or eighty wide. The supply of water brought down by the brook was sufficient for their needs, and they were engaged in cutting passages through the partly submerged grassy tussocks for the purpose of reaching the wooded shores with greater ease. Everything promised well when a prolonged spell of rain caused them great anxiety. The stream increased its volume until it was a raging torrent which swept all before it, clearing the banks of any debris that had been deposited by the spring floods. The dams, whose crests were many inches under the water, were threatened with complete destruction. Something must be done, and done soon, and the beavers did the only thing possible under the conditions. They tore open a great gap in the larger structure. It was a dangerous task, for the pressure of the water was terrific. However, by working carefully they succeeded in liberating an immense volume of water and so saved the dams. These were again repaired as soon as the flood subsided, when the entire work was not only strengthened but increased to a still greater height. so that it was nearly five feet at the highest point. This necessitated a still further increase in length, with corresponding increase in the size and depth of the pond. Fortunately their lodge had not been seriously injured by the unexpected rise of water. The floor, it is true, had been submerged, which was quite natural, as it had been only four inches above the normal water level. One thing leads to another, and the additional work on the dam meant that the floor of the lodge must also be raised, so they cut away part of the ceiling and used the material thus obtained for the flooring. This in turn meant putting still more material on the outside of the house, as the thickness of the walls needed to be not less than three feet and the roofing a foot and a half, without the final coating of mud. September with its cool clear days was in its last quarter by the time the young couple had everything in order. The white frosts at night warned them of the approaching cold season for which full preparation must be made if they expected to live in comfort. Most important of all the tasks was the food supply. So they made a tour of investigation among the trees to see that they were in proper condition for being stored. Several small birches were examined and partly cut in order that they should dry thoroughly before being felled. They dry better and more rapidly while standing, so after the beaver had girdled them they went off to a small aspen grove and commenced serious harvesting. The trees were nearly a hundred yards from the edge of the pond on the further side of a piece of boggy thicket. So before any wood could be brought to the water a roadway had to be made. Part of this was really a canal which was cut straight through the swamp and from which all obstructions were carefully removed. When finished it was about three feet in width and a little over a foot deep. On shore the path was rather wider, and led directly from the end of the canal, to the centre of the grove where it forked so that three different paths gave access to the field of operations. This accomplished, the beaver began felling the trees. As each one dropped, and it took but an hour or so to bring down a tree six to eight inches in diameter, all the branches were neatly cut off close to the trunk; these were carried down the road to the canal, the smaller ones being held, butt foremost, with the teeth, while the beaver either walked on all fours or only on his hind legs with the tail used as a balance. Some branches which were extra large were dragged along as the animal walked backwards until he reached the canal. From that point the work of transporting the wood became easier and he swam, leading the floating load with his teeth. In this way he proceeded through the canal then across the pond to the lodge near which they had decided to place the wood-pile. Sometimes, instead of immediately diving arid taking the cutting to the bottom they would leave it floating close to the lodge, perhaps with the idea of allowing it to become water-soaked, so that it could the more easily be taken down. The journeys were quickly made, and little or no time lost, except when occasionally, on the return trip, they would stop and take a short feed.

The trunks of the aspens were cut into convenient lengths varying from two to eight or ten feet, according to the thickness. The shorter pieces were rolled or pushed down the path, the longer ones pulled, sometimes both animals working together if the log happened to be unduly heavy, using not only their hands and chests, but also their hips. The entire operations proceeded smoothly and with perfect system and in absolute silence. Nothing was wasted and everything was as tidy and orderly as possible. Interruptions occurred at times when suspicious scents tainted the air and caused them to suspect the proximity of a foe. They would then scuttle off quietly to the water and stay there so long as there was any cause for alarm. Sometimes they dared not approach the aspens for an entire night, owing to the presence of wolves, foxes, or other predatory creatures who consider beaver meat quite a luxury. On these occasions they did not avail themselves of the excuse to stop all work, for there was plenty to be done. The dam could always take a little more mud on the facing or more brush and logs on the lower side, and the building of secondary or supporting dams had to be considered. Who could tell but that the main structures might at any moment give way under the pressure of water, or the still greater pressure of broken ice, that enemy to all dams in the northern countries, whether built by man or beaver? Strong indeed must be the structure that will withstand its onslaught, when borne by the spring floods it hurls itself at every obstacle. Well-built bridges are smashed like matchwood, great trees are uprooted, banks are torn down, and ponderous boulders are swept before it, as creaking and groaning it grinds and forces its impetuous way in the company of the raging streams. The beaver, knowing the possibility of such an onslaught against their dams, whether by experience, instinct or reason, finally decided to erect smaller dams below the main structures. Owing to the narrowing of the gully it was only necessary that these dams should be very short, one near the larger outlet being twenty-five feet long the other fifteen, but as the ground sloped suddenly they had to be fairly high in proportion to their length. The work was carried on regularly and without difficulty, as there was very little water passing down the stream and building material was everywhere abundant. Autumn stole upon the beavers while they were engaged on their many tasks. The days shortened, so that the increasing length of the nights gave them more working hours. The nights, too, were much colder, and the trees took on their wonderful clothing of scarlets and yellows. Those persons who have lived all their lives in the sombre east can have no idea of the glories of the western colouring. No pigment is richer or more brilliant than the leaves of these northern trees. The intense yellows of the birches and aspens, the scarlets, crimsons and oranges of the maples, and the endless array of purples and reds of the shrubs combine to make these woods a feast for the eye, beautiful beyond all power of description. It is the signal of the fall of the year, the advance guard of the long season of rest, silence and hardship, when the inhabitants of the wilds are hard pressed for food and the weakling and the improvident succumb under the great test of fitness. The survival of the fittest is the inexorable, pitiless law of nature which demands of her offspring perfection in power and resource. Those who are unable to battle against the frightful odds fall out of the ranks and are quickly forgotten by the survivors, the winners in the great race. With the falling of the leaves the maples and birches which had been girdled or marked by the beaver a week or two earlier became ready for cutting, so the busy animals attacked them with their customary vigour and determination. It was not like felling the soft aspens, through whose tender wood their teeth bit with but slight opposition. These hard trees demanded far greater effort, but the keen-edged teeth tore out the great chips, and each night saw the fall of at least one silvery birch or grey-coated maple, and the pile of winter wood grew larger and larger till it covered an area of full eighteen feet in diameter and five feet in depth. It was hard work, but it did not daunt the provident creatures, who knew well enough that on the fruits of their autumn labour must they depend for nearly half a year, so the harvest was gathered without murmur or complaint. Colder and still colder were the nights, and by the end of October ice formed around the margin of the pond and wherever the water was sheltered; quite often after dragging the cut branches down over the carpet of crimson and gold leaves with which the ground was covered the beavers had to break a way through sharp-edged ice, and it warned them that it was time they should attend to the outside plastering of the house. This was a simple enough job, but still it must be properly done. Not too much mud should be put on at one time, but layer after layer, pressed in firmly among the woodwork. As each coating contracted under the influence of the frost another coat was applied, so that gradually the lodge assumed the appearance of a great mud heap, which, as it froze, became stronger on the outside and warmer in the cosy interior. At odd times during this season they collected bedding material. A little grass was cut and carried in, but grass gets wet and soggy and is not really a serviceable substance. Finely-shredded wood is better. So they cut down a cedar, which is the best of all trees for the purpose, and taking it piece by piece into the lodge tore it into fine shreds and made a deep bed, which was sanitary as well as comfortable. Of course certain parasites would make their home in it and cause the beaver great annoyance, but that could not be avoided. All they could do would be to use the curious split second toe-nail of their hind feet as a comb with which to make their daily toilet and dislodge the intruders.

As the home was nearing completion the beavers took in a pair of muskrats as uninvited tenants — for, curiously enough, muskrats nearly always make a winter home in the lodge, not living actually in the main room, I believe, but making a small nest for themselves in the wall, the entrance to which is either through an off-shoot of the regular burrows or else one made entirely by themselves. Apparently they do not interfere in any way with the rightful owners of the lodge, unless possibly they steal some of the smaller twigs from the wood-pile, for they too depend to some extent on bark for nourishment, though grass and roots form the greater part of their diet. Some writers maintain that the muskrat, or musquash, is an enemy of the beaver, who kill them whenever the opportunity occurs. This may be the case in some parts of the country, but I have never seen the slightest evidence of it. On the contrary, I have watched the muskrats going in and out of the lodges and working about the wood-pile while one or more beaver were there, and they paid not the least attention to their little cousins. So also when the beavers fell a tree into the water the muskrats will keep them close company while they are at work. I have seen the little fellows cut off small twigs from a birch tree from which two beavers were busily engaged in stripping bark and branches and carry it away to some hiding place unknown to me. Whether or not the muskrat does much damage to the dams is not apparent. They have their regular crossings over the tops of the dams, but I have never found any sign of damage which could be directly attributed to them. This, however, can scarcely be said to prove them innocent, because the experience of other observers does not altogether agree with mine. The mere fact that the beaver allow the muskrat to live unmolested in their lodges should at least be regarded as an indication of the seemingly friendly relations of the two. In both Newfoundland and Canada I have almost invariably noticed on approaching a lodge very quietly that at the vibration caused by my walking a muskrat will be seen slipping out from the lodge under water, a few bubbles rising to the surface as he swims near the bottom. At first I used to believe they were young beaver, but that idea was soon dissipated by the little fellows coming up close to where I lay concealed, when I could identify them without any doubt. By the middle of November the lodge in which our pair of beaver lived was completely finished. It was smooth and tidy, with scarcely any sticks showing, nothing but mud, and roots, and a small amount of grass and sod used as an outside plastering. About this time the pond froze over completely except above the spring to which allusion has already been made. Only on very cold nights was there sometimes a thin layer of ice over this part, but even this usually melted during the day time. As winter settled down on the country, the beaver were seldom seen out of doors. Occasionally on a particularly warm sunny evening, one would come out through the spring hole and take a look over the house. But there was no work to be done, so the beaver resigned themselves to the long season of rest and inactivity, welcome, perhaps, after their two months or more of really arduous labour. One day was much like another. Having nothing better to do, they slept most of the time, coming out only for an occasional swim in the ice-covered pond or to get some twigs from the wood pile. These they would cut off in convenient lengths, take into the house and eat the bark. This done, the peeled stick would be carried out and left floating beneath the ice, useless except for building material the following summer and autumn, when repairs to lodge and dams would be needed. Nothing of particular importance occurred during the winter months. The pond, like so many others, lay hidden beneath two feet of sparkling ice over which was spread another two feet or more of concealing snow. Only a slight white mound showed where the beavers’ lodge stood, and from the top of this mound a scarcely perceptible film of vapour rose to show the place was occupied. The inmates knew nothing of what was happening in the great white world. Blizzards might rage, spreading terror among the unhoused dwellers of the woods. Tall, straight trees succumbed before its unseen power, and crashing to the hidden earth unheard in the roaring of the wind were soon buried beneath the wind-driven snow, torn and splintered stumps alone standing as gravestones to mark where they had lived proudly for so many years. The still cold i nights when the thermometer might drop to thirty or forty degrees below zero, so that trees, chilled to the core, would burst with a sharp report which awakened the echoes of the dark mysterious forests. The clear white sun might shine with bright but heatless glare which revealed the sparkling crystals of the frozen snow but gave scant comfort to any living creature. Or the pale moon might rise and creeping slowly across the sky watch the great E game of life and death, where the hunter and the hunted strive to outdo each other in alertness, when tragedies were registered by the red seal of blood where the victims fell. Nothing of all this was known to the beaver who, housed so comfortably by their own foresight and industry, lived in complete peace, fearing nothing but man and otter during this season so dreaded by the homeless. Who shall say whether they even knew of the many visits paid to their lodge by wolverines, lynx, fishers and wolves? These hunger-driven creatures could smell the hidden beaver as the scent rose from the house, and their tell-tale footprints on the fresh-fallen snow showed how often they approached the house as though in hope of finding some unexpected way of getting into it. Well they knew that their visits were fruitless, for not even the powerful wolf could dig his way through the icebound, tangled walls. Perhaps the beaver could hear or smell their foolish visitors; if so they must have experienced unbounded satisfaction in the knowledge of their self-made security, which was the result of so much hard work and skill. Winter at last began to give way to the lengthening hours of sunshine. The weather ceased to be so piercingly cold, and the throbbing shafts of light from the aurora borealis no longer brightened the sky at night. The snow became soft and slushy, and the ice broke away from the banks of lakes and rivers. As the streams, fed by all this melting material, grew with alarming speed, the stillness of the forest was broken by countless tons of moving ice which bounded along in the seething water, now piling up in great walls as some obstacle barred its path, then breaking loose and tearing all before it. The upper end of the beavers’ pond was a mass of broken ice brought down by the stream. For some time it could not break its way through the solid sheet which covered the pond. Gradually the unceasing flow of water forced a passage through the dam where the ice again piled up as though impatient of the delay. During these days, the beaver frequently came out for an airing, often going into the woods in search of some fresh food. It was a dangerous undertaking, for their enemies were thin, hungry, and keenly alert, and the slightest prospect of beaver meat gave stimulus to their cunning. Several times during those first visits to the woods did the beavers escape by an all too-narrow margin, reaching the water only just in time to miss the white fangs of their quick-footed enemies. By the end of March all trace of the winter’s snow had vanished except in the darkest glades where the sun did not penetrate. Gradually, the first signs of spring became visible. Small green shoots appeared among the dead leaves and mosses, the buds on the trees began to swell and give promise of foliage, and by the middle of April the woods were tinged with the tenderest green of the new leaves. This was the most important period of the beavers’ life. Already the female was becoming restless, making and remaking the bed of shredded wood and grass. She did not appear to care for the society of her mate, who kept away from her during much of the time. Finally he left the lodge, and sought a temporary home in a bank burrow, and it was but a few days later that in the lodge could be heard the faint whining cry of a newly arrived family of three. Three small, furry imitations of their parents, about twelve inches long and rather greyer in colour than they would be later; their ears were very dark and their eyes were open from the first day,1 and their teeth good miniatures of those with which their parents had done so much useful work. Occasionally the young father came into the lodge, but he seldom stayed long, evidently he considered it wise to let the mother have the place to herself and young. For two weeks she kept them in the dark, warm house, nursing and watching over them with the true solicitude which is so wonderful and so exquisitely unselfish in what we term the lower forms of life. Willingly would she have sacrificed her own life if occasion demanded. No danger would have been considered too great if her offspring were in peril, but fortunately they were safe and she only had to nurse and caress them while they got their strength. In less than three weeks, they made their bow to the great outdoor world, swimming about without effort or fear, in evident enjoyment of the bright sunlight that was such a contrast to their dark home. A short swim sufficed for the first day, and one by one, of their own accord, they dived (without having to be taught as our fanciful writers would make us believe) and returned to their lodge to dry off and sleep after these first exertions. The day and weeks that followed were filled with the joy of living. Spring flowers blossomed and passed to give way to later ones, the birds returned from their winter journeys in the balmy south, and filled the green-clad forests with their varied songs. It was their season of courtship and nest-building, all following the laws of their kind with a precision that no man can understand. At a certain time the home of each particular species would be completed, nor did they vary more than a few days from one year to another. What almanacs did they consult that they should be so exact? Yet had they not arrived, each species at its own exact time, all arrayed in their brightest dress, whether of yellow, blue or scarlet, or the more sombre hues, to stay in the northern land for a definite period and for a definite purpose? The young beavers played about to the music of the woodland birds, yet no one dare say that they paid the slightest attention even to that most exquisite of songsters, the hermit thrush, whose rich, full notes sound like the call of some happy, peaceful soul that has passed away to the land of shadow and mystery. Amid such surroundings was it ordained that they should live, knowing few cares or troubles, spending the hours in happiness, innocent as yet of the fear of man. They were a playful trio, frolicking about in the water like kittens on land, playing among the fluffy, windblown willow seeds that raced across the water like tufts of eider-down, or later among the broad leaves of the spatter-dock and the water-lily, filling the snowy petals of the flowers with sparkling drops as they splashed the water with their diminutive tails. They played hide and seek, like children, pushed each other off the half-submerged logs exactly as boys would do, all the time gaining the strength and agility which play is destined to give. When the sun was shining they would often sit on the banks of the pond and after making a careful toilet indulge in the luxury of a sun bath, sleeping, yet ever watchful. No one could say at what moment during the day a silent-winged hawk might swoop down on them, for they were small, and tender enough to tempt the appetite of those that feed on flesh. When a hawk is seen, even though it appears as a speck in the heavens, the little furry creatures will scramble into the water and either resume their play or go into the lodge for greater safety, usually giving a little, child-like cry of alarm, and on entering the lodge they hold an animated but very subdued conversation like the muffled whining of very young babies. While still quite small the beaver took to solid food, nibbling the bark from thin, tender twigs, so that the process of weaning was very gradual. During the summer months they spent much of their time outdoors, frequently without their parents; at the slightest suspicion of danger, they would slap the water with their tails in quaint imitation of their parents. The sound they produced was faint, but still loud enough to arouse the mother, who usually came out to see what threatened her little family and make them seek shelter either in the lodge, a burrow, or more frequently among the thick grass which lined the pond. When they were about two months old they took up their quarters for a time in a large burrow which had been made for the purpose, the lodge being left, probably for the annual spring cleaning, which simply means the destroying of the insect parasites (platypsyllus castoris), with which the bedding becomes more or less infested, but which is believed to be dependent on the living creature for its own existence. Only too quickly the summer passed. The lowering skies and cooler nights foretold the coming of autumn. But the warm, bright weather had served its great purpose. The birds had given to the world a new population to take the place of those that had died or been killed. In the warm days, the young had grown and thrived on the vast insect life which abounds in those northern woods. The trees had flowered and fruited, that new seeds might be sown and young trees grown to fill the ranks of the old and fallen. Smaller plants had gladdened the woods with their minute spots of colour and furnished fruits and seeds to feed many creatures during the coming winter. The wild meadows were filled with new grasses to feed the deer and others that were dependent on such simple diet, and everything had gone along in its wonderful, orderly way, arranging supply and demand with supernatural accuracy, leaving the annual balance-sheet audited by the unseen power that takes charge of all our accounts, whether it be the tiny and apparently insignificant chickadee whose duty it is to protect the forests against the ravages of certain insects or man whose responsibilities are so far-reaching.

The young beaver family had thrived and grown, and were ready to assist their parents to the best of their small ability, and even if their help was of little account they could at least learn, by watching, how the various tasks were accomplished. Not intentionally did the parents undertake their education. That only happens in story-books in which the authors try to humanise the animals and make them follow our own further advanced and complicated methods which change as our lives become more and more complex. The animals have a very marked inherited instinct to follow in the footsteps of their predecessors which causes them to do things naturally. We think that we teach a child to walk, but if we made no effort to do so the child would naturally walk because of the inherited tendency to do that which has been done by ages of ancestors. As the beavers swam, dived and fed without being taught, so also did they cut wood with their teeth without having to be shown how to do it. By observing the work of their parents they undoubtedly acquired a greater knowledge of how things could be done with the least effort and best results. Whether they knew why trees were cut, branches stored, lodges and dams built before they had experienced the rigours of winter, we cannot say, for we do not even know definitely how animals impart knowledge and exchange ideas. By the time that occasional spots of scarlet pointed out the earliest of the maples, and the migrating birds had started southward, the beavers began seriously to repair the dams; fresh material was added, and the height and length slightly increased, the lodge also needed material, as the heavy rains had washed away much of the earthwork. The branches which had been peeled during the winter for food were now utilised in the various repair works. Even the inside of the lodge required attention as it was rather small for the increased family, so a little excavating was done until it was large enough to accommodate the five occupants. Another entrance was also made in case of emergencies. Tree cutting began as on the previous year as the colouring of the trees was passing its prime. But now they needed a much larger supply of winter food as there were more than twice as many mouths to feed and none of the supply gathered a year ago was now fit for food. Some of it was dragged on to the house and dam, but most was left to anchor the fresh cuttings, and to form an arched way to the newly made tunnel. While all these tasks were being accomplished, the young beaver followed their parents, sometimes biting down very small shrubs and carrying twigs to the food pile. They even brought up little clumps of mud and put them on the lodge and dam. From one task to another they went like restless children, always busy doing something or nothing. They had almost completely given up coming out during the day time, and seldom appeared until an hour before the sun had vanished behind the trees. Toward the middle of November, the first flakes of fluffy snow drifted slowly and aimlessly down on the frozen earth. It was the advance guard of the storms which would soon follow. Very gradually the white mantle spread, and the soft browns, greys and greens of the land were hidden and the beavers snuggled down in their cosy warm beds, contented and confident that winter with all its hardships had no terror for them. Their house answered their every purpose, while outside, enclosed securely beneath the ever thickening ice, was their harvest of wood: maple and birch and ash and poplar, and many other kinds, forming altogether a diet sufficiently varied to satisfy the most fastidious of beavers. Here in their well-planned home we may leave them for the long winter, during which time they grow fat and live a lazy life. With the coming of spring, the father beaver was once more requested to leave his home for a new family was expected. He took up his quarters in the burrow where they had all lived during part of the summer. On coming into the lodge one day toward the end of April, he was welcomed by the tiny whimpering of four newly-arrived kittens, exact duplicates of those that had come just a year before. The founding of the new colony seemed well assured now that instead of two there would be nine to do the various works. Of course it meant an increased drain on the food resources of the neighbourhood, which was none too abundant in the immediate vicinity of the pond. During the weeks following the arrival of the new family, the father beaver spent much time wandering about as though making plans for the future. Perhaps he realised that the food trees were becoming somewhat scarcer near the water, and that harvesting for the coming autumn would involve a lot of very hard work. This would seem to have been his course of reasoning, though there is no proof, and perhaps the extended wanderings were simply the result of restlessness after long months of inactivity. Within a distance of several hundred yards all around the pond his journeys took him and little escaped his keen eye. Among other things he noted to the eastward of where the short canal had been cut that there was a small knoll on which there was a dense growth of aspens whose silvery leaves trembled incessantly in the slightest breeze; a very promising supply of food it was, but unfortunately it would mean a long, difficult portage of nearly two hundred yards, all over rough ground. He stored this information away in his brain, but did not avail himself of it for many weeks, during which time he made frequent trips, chiefly down the main stream, stopping here and there to place a small mud pie signal so that other strolling beaver would know he had been there. Sometimes he was accompanied by one or more of his year-old children, but Mrs. Beaver stayed at home to look after her young ones, who were thriving as all healthy wild creatures do. During the late afternoons she would lie on the surface of the water and watch the youngsters playing. It was scarcely safe to leave them entirely alone as they often became so engrossed in their games that they would have fallen easy victims to any enemy. One day she left them for a few minutes, going under water in search of some dainty morsel of food. As she rose to the surface her quick eye caught sight of a goshawk flying low toward her young who were sunning themselves on the bank, utterly oblivious to the impending danger. Quick as a flash she gave a slight cry and struck the water with her large heavy tail. Instantly the four baby beavers made a rush for the water. The warning was too late, however, for the goshawk, like a flash of lightning, swooped down and caught one of the wretched creatures, not stopping in its powerful flight, but carrying its prey into the woods where it was lost to view. Like most of the tragedies of the wilds, it had happened quickly, and with scarcely any disturbance. The mother beaver took her three remaining young into the lodge, where she remained for a few minutes; then she came out quietly, and after making sure that all was safe, swam slowly to where the four kittens had been sunning themselves so peacefully only a short time before. On landing, she nosed about until her nostrils found the scent of her lost one and the hawk. She raised herself up, sitting on her hind legs with her small hands hanging by her side and gazed wistfully toward the woods which had swallowed the little kitten. A low cry escaped her lips, but no answer was returned. Again she repeated it without result, her nostrils quivering all the time as though trying to get the faintest hopeful scent. In her heart she well knew that she would never see the one she sought again, yet the hopefulness of despair compelled her to utter the mother’s call. It was all over, the lesson was learned, both by herself and her family, and she swam back, diving without noise, and disappeared in the lodge where three frightened and hungry kittens awaited her.

Fortunately no other misfortune marred the happiness of the little colony during the summer. The weeks were spent in play and enjoyment and in investigating the surrounding country. Shortly before the approach of autumn the plans which had probably been formed many weeks earlier took form. The aspen grove must be reached and it was decided that the old canal should be extended from the part which had been started the previous year to where the trees grew. Excavating a suitable trench was not easy work, but the two old beavers, with the assistance of their three well-grown children, undertook the task. The canal started at the lake. It was about two and a half feet wide and fifteen inches deep. Some of the mud was taken out and carried into the pond, but most was piled up on the sides. It ran in a direct line toward the aspens, but after it had extended about seventy yards, the rising land made it necessary to dig down to a depth of two feet or more in order to have sufficient water. Evidently they could not continue in this way, as it would mean making a trench over four feet deep before the desired end could be reached, so the intelligent animals constructed a small dam and continued the ditch at a higher level. Two more such dams were found necessary, each raising the water to the proper level. On reaching the foot of the knoll on which the aspens grew, the canal was divided into two wings, but in these there was a lack of water which made them almost useless except during wet weather. The father beaver remembered having seen a tiny stream which flowed not far from the end of the longer wing, and, taking advantage of this, he cut a narrow ditch only a few inches wide and diverted some of the water from the streamlet to the canal, so that it had sufficient for its purpose. It was a clever piece of work and showed well how highly developed is the engineering skill of the beaver. The weeks passed with alarming rapidity while this great task was being accomplished, and though the animals worked literally tooth and nail, they had to bestir themselves in order that everything might be in order before winter set in. A considerable amount of work was necessary on the dams, not only in repairing the original structures, but in extending them once more so that the size of the pond could be slightly increased. Then also the lodge needed material enlargement in order that the eight beavers might be able to live comfortably. It was altogether an extremely busy autumn and all hands worked with a will, apparently without any supervision, each doing what he or she considered most necessary. By the time the leaves began to fall and carpet the earth with their varied and brilliant colours, but little harvesting had been done. Perhaps they knew that aspens are easily cut and that far more material could be gathered in a given space of time than if large tough-wooded birches and maples were to furnish the supply. However that may be, the cutting of the aspens did not begin in earnest until November. Then, as though suddenly realising the lateness of the season, a vigorous attack was made on them. Over a dozen were felled in a single night. Each one was quickly stripped of its branches and cut into convenient lengths and in this way carried down piece by piece to the canal and through it floated down to the pond and then to the wood pile. In going down the canal, each piece of wood was lifted over the dams, which soon showed much sign of hard wear, so that constant repairs were necessary. The year and a half old beavers did nearly as much work as their parents, and for nights there was an almost constant procession coming and going between the lodge and the head of the canal. With astonishing rapidity the store grew, and it would have been difficult to estimate the number of cords of wood it contained. Even during the freezing nights, when ice formed on the still waters, the beaver continued their harvesting, frequently having to break the ice which formed along the canal. Finally, one evening, they came out of the lodge to find their canal useless. Over half an inch of clear, “black” ice had formed over its entire length and they could not break it. So the aspen grove, or what was left of it, was abandoned, the smooth, gleaming white stumps bearing silent testimony to the remarkable activity of the beaver. The season of work was practically at an end. Here and there they managed to find a tree within their reach, but only where the streams ran into the pond and so kept the ice from forming could they bring any supplies. Around the lodge and wood-pile the ice was solid, except the region of the spring where but little formed, so that whatever branches were brought had to be transported for a considerable distance under water. When they finally rested from their labours the store was ample for their needs, even though winter should last beyond its usual time.

The months that followed were in no way different from those of the previous winter. But when spring came, instead of the father beaver leaving the lodge alone, he took with him his three older children, and lived with them in the summer burrow. The mother, who later gave birth to four kittens, lived in the lodge with the three survivors of the previous year. This season a change was decided upon. The family, now numbering twelve, would crowd the lodge beyond its capacity, so the three older ones were given to understand by their parents that they must seek homes for themselves. One went off alone to see the world, and as he never returned it is likely that he either found a mate who, like himself, was a wanderer, or else he joined another colony. Fortune was kind to his two sisters, who for the moment wished to remain in the vicinity of the parental pond. A small family which had its home a couple of miles further down the stream had met with disaster. Fire, that most terrible of all foes, had carved its deadly way around their pond, leaving a charred and blackened mass where all had been so green and alive. Their food supply gone, they had been forced to abandon the house which had sheltered them for two happy years. One road was as good as another, and it happened that they came along the stream on which our beaver lived. While journeying along, they came to some of the little mud-pat signals made by our beaver. What those silent signals told them no man knows, but they came on with renewed hope, and one day arrived at the pond we have been watching. There were four of them, an old pair and two young males, their children. Their presence was soon known to the resident colony, but there was not much in the way of introductions. Sufficient for them that they were accepted as friends, and allowed to remain for the present at least. As might naturally have been expected, the two young males decided to take unto themselves the two young females as wives, and one of these new pairs, delighting in their freedom and independence, went away to some new part of the country and began housekeeping according to their own ideas. They were mated for life and therefore it was only right that they should select some place which would allow the starting of a new colony, with ample room for expansion. Their decision was wise, for had they remained the pond would have been somewhat overcrowded, and that is quite contrary to the rules and regulations of beaverdom. Everything is regulated from the point of food supply, and so according to the resources of the neighbourhood must the growing of a colony be limited. The young pair that remained decided to build their lodge on the little island on which the original one was placed, but a dividing ditch was cut so that each lodge was on its own individual island. The older pair of visitors, not considering it wise to encroach too much on the hospitality of their new friends, made a pond for themselves by damming the smaller stream that flowed into the lake and which had originally joined the main stream. In their newly made pond they arranged to build a lodge on a point of land which they severed from the shore by cutting a broad channel. This seemed an almost unnecessary waste of labour if it was intended as a means of protection, for any animal large enough to be regarded as an enemy could easily jump across. It might, however, prevent tunnels being made from the land which would allow of access to the interior of the lodge. During the summer, the beavers wandered about the country and were seldom much at home, but towards the middle of August they returned for good, and slowly did what work was necessary in the way of building and repairing darns and lodges. The older pair of visitors kept pretty well to their own pond, building their dams and lodge without assistance from the rest of the colony, who had quite enough to do to attend to their own needs. When wood harvesting began, the two families in the larger pond made a single wood-pile which would serve them both. With eleven mouths to feed it was necessary that the store should be even larger than on the previous year. Most of the harvesting was obtained from the aspen grove at the head of the canal, and the number of trees cut was past all belief. The woods resembled the scene of serious logging operations as carried on by men. Paths were cut intersecting the whole knoll and everything was most orderly; each stump was a triumph in the art of wood-cutting, clean and smooth as though cut by an experienced lumberman. No waste was to be found anywhere. Every trunk whose bark was in proper condition was neatly divided into convenient-sized sections and removed to the wood-pile, not even a twig was left. Besides the aspens, the beaver occasionally undertook the more laborious task of cutting down large birches, the bark of which has a very different flavour. These birches, growing as they did among the older trees, often presented difficult problems. One large one in particular, which had a very heavy top of branches, was cut after many nights of hard work. Unfortunately it lodged in a neighbouring birch and would not fall. Another cutting was decided on and continued until the twenty-two inches (diameter) had been gnawed through. But even this did not accomplish its purpose, for, though the trunk shifted a few feet, the top remained entangled. The tree against which it rested in such an aggravating way was nearly as large as the one that had been cut, but even that did not daunt the little wood-cutters, who went to work with renewed determination to cut through its massive trunk. By the third night they had cut most of the way through, but the trunk, creaking with the great weight of the tree which leaned against it, filled the beaver with fear, for should it fall there was great danger of being caught beneath the mass of branches. So they left the task unfinished, perhaps hoping that the two trees would fall of their own accord. Fortune favoured them, when a few nights later a violent storm swept over the country, the roaring winds screeched through the forest, snapping off branches and uprooting many large trees. The winds lashed the water of the lake into a mass of foam, threatening even to tear the wood-pile away from its moorings. For two days and two nights the gale raged without a pause, and during that time the beavers kept in their lodges, for well they knew the dangers of falling timber. At last the storm passed, and the roaring of the wind and creaking of the trees gave place once more to the wonderful, overpowering stillness of the forest lands. Once more the pond reflected the beauties of the encircling woods. But a great change had taken place in the appearance of the country. Before the storm, the forest was a parti-coloured mass of dark green, golden yellow, orange and scarlet, a shimmering kaleidoscope of colour, but the ramping wind had stripped the branches of their gorgeous coverings, and left the woods a sombre symphony of greys and greens, while the ground was strewn with wind-blown wreaths of brilliant leaves.

When the beaver came out to see what damage had been done, they found that the lapping water had torn away the upper side of one of the lodges and carried off many large poles that had been laid on the roof. The dam, too, had suffered, and would need countless handfuls of mud to take the place of what had been washed away. A visit to the canal showed how that too had been damaged. Trees growing along its banks had been uprooted and the ditch was made impassable by the fallen branches and débris. True enough, they would find much material among the windfalls that could be utilised, but the work of clearing the canal was serious and occupied many nights. During this time they had been too busy to visit the lodged birch and its partly-cut neighbour. But at last one of the older beaver went ashore, probably with the idea of seeing what had happened, and he had the satisfaction of finding both the trees lying on the ground in a confused mass. Here indeed was a harvest which was worth considering, and forthwith he began cutting off a branch, which he immediately carried down the mossy bank to the water and across the pond to the wood-pile. One of the other beaver, seeing him come so heavily laden, surmised the truth and followed him back to the source of such richness, while she in turn was soon followed by several others. Before doing much cutting, however, they decided to make a better road, as there would be a very great number of loads to be carried. A direct course was therefore chosen from the fallen trees to the nearest water. In a couple of hours this was finished, for all worked together with but one end in view. No foreman directed their efforts, each individual seemed to know exactly what was needed, and each did what was necessary without the slightest instruction or advice, and therein is one of the great mysteries of beaver work. How is it they work in complete concert and harmony even when engaged in most difficult undertakings? No plans are drawn, no orders given so far as we know, and yet the work is carried on as smoothly as though done by a body of skilful artisans under the instruction of a trained foreman who in turn receives his orders from a competent engineer. The first thing to do after making the path was to cut off the outer branches which lay on the ground. This alone occupied two nights. Then, by climbing along the leaning trunks, all the larger branches were neatly bitten off so that the trunks; relieved of their support, came gradually to earth and were divided into lengths varying according to the diameter; nothing over eight inches through being carried away. But even the thickest parts of the trunk that had to be left were not wasted, for the beaver ate all the bark which was suitable for food. It was noticeable that the two old beavers in the upper pond took no part in cutting up these trees. Their colony was entirely separate, and they must do all their own cutting. In other words, poaching was not allowed. In about ten days, nothing remained of the two tall trees but the stumps, two lengths of partly peeled trunks and a mass of large and small chips that were beaten into the well-trampled ground, these and the scarred pathway to the water, and the greatly-augmented wood-pile. From that time up to the freezing of the pond the usual preparations for cold weather were carried on, so that when the pond froze and the country received its winter winding-sheet everything was in readiness. The lodges had been plastered, bedding gathered, the dams thoroughly overhauled, and the outdoor store-house a credit to the foresight of the little caterers. The winter passed without excitement. During January, a few days of unusually mild weather produced a great thaw, so that the ice, weighted down by the melting snow, broke away from the shores. The beavers took advantage of this, and came out to bask in the cold sunshine. Some climbed on the lodges, while others more adventurous in spirit went ashore, their broad, deep trails marking their short journeys to the woods. Besides this little holiday no other event broke the monotony of the long imprisonment. At last came the welcome death of winter, and the gradual arrival of spring which saw the colony increased by no less than twelve new arrivals. The founders of the colony boasted of a fine family of five new kittens. In the lodge next to them there were three, while the pair in the upper pond had four, and all these families were born within a period of two weeks. The colony might now be said to be in a flourishing condition, with a population of twenty-five, where less than five years before there had been but two. Unfortunately, such prosperity was not destined to continue, or we might have seen the colony double itself by the following spring. That would have meant the facing of new problems in the way of expansion, for even after allowing the departure of two or three pairs, which would certainly have occurred, the remaining forty or fifty would have made great inroads into the food supply. The old dams would have to be enlarged and new ones built so that a larger area might be flooded. The canals would have to be extended and in every way great changes would be bound to take place. During the month of July, when the whole country was throbbing with life and activity, when everything presented such a marked contrast to the four sombre months of winter, the unwelcome sound of man’s voice broke the peacefulness of the little pond in the woods. A fisherman, anxious to explore the stream in hopes of finding a good place for trout, had come down from the lake above. With him was an old guide who lived, as so many of them do, by guiding fishermen during the summer, and big game hunters in the autumn, while the winter, or at least the early part of it, is devoted to trapping, the other part being often spent in lumber camps. It was late in the afternoon when these two intruders arrived. The beavers, lulled into a dangerous security by the long period of absolute God-given peace, were playing about the pond, the young indulging in their games with all the joy of youth and inexperience. On one of the lodges lay the founders of the colony, basking in the warm yellow sun, when suddenly the sound of voices reached their ears, followed almost immediately by the tainted breeze. No second warning was necessary. Silently the two slid off the lodge, but no sooner had they reached the water than each struck it a resounding smack that sent up a shower of sun-kissed drops. The command to dive was imperative, and every beaver in that pond and the upper one vanished instantly, and without a sound, to meet later in several of the burrows which had been made along the shore. The fisherman was much interested in the scene; but he was after fish, not beaver, and he would far rather have seen the surface of the pond broken by rising trout. Had he but known it, that water contained many fine fish that had come down from the upper lake to enjoy the rich food in the beaver pond. The trapper saw the prospect from an entirely different point of view. Here was a thriving colony of beavers that represented perhaps a hundred and fifty or two hundred dollars to him. He walked round the pond, noted the size of the chips which indicated well-grown beavers, and, what was of great importance, no one had been before him. He would keep the news of the lucky find to himself, and as soon as the shooting season had passed, he would come armed with the deadly trap to destroy the colony that was engaged in a great, far-reaching work that he did not understand. Comparing the beaver and the man, we might well ask which was doing the greater good. The one bent only on destruction, while the other, though so insignificant, was devoting his entire energies to conserving, to doing that which, strangely enough, would be of greatest benefit to the race which was for ever seeking his extermination — surely an ironical fate, and one that seems lacking in the elements of justice.