| Web

and Book

design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2021 (Return

to Web

Text-ures)

|

(HOME)

|

|

BROCKENHURST

The English

gardens in which Mr. Elgood delights to paint are for the most part those that

have come to us through the influence of the Italian Renaissance; those that in

common speech we call gardens of formal design. The remote forefathers of these

gardens of Italy, now so well known to travellers, were the old

pleasure-grounds of Rome and the neighbouring districts, built and planted some

sixteen hundred years ago. Though

many relics of domestic architecture remain to remind us that Britain was once

a Roman colony, and though it is reasonable to suppose that the conquerors

brought their ways of gardening with them as well as their ways of building,

yet nothing remains in England of any Roman gardening of any importance, and we

may well conclude that our gardens of formal design came to us from Italy,

inspired by those of the Renaissance, though often modified by French

influence. Very

little gardening, such as we now know it, was done in England earlier than the

sixteenth century. Before that, the houses of the better class were places of

defence; castles, closely encompassed with wall or moat; the little cultivation

within their narrow bounds being only for food — none for the pleasure of

garden beauty. But

when the country settled down into a peaceful state, and men could dwell in

safety, the great houses that arose were no longer fortresses, but beautiful

homes both within and without, inclosing large garden spaces, walled with brick

or stone only for defence from wild animals, and divided or encompassed with

living hedges of yew or holly or hornbeam, to break wild winds and to gather on

their sunny sides the lifegiving rays that flowers love. So

grew into life and shape some of the great gardens that still remain; in the

best of them, the old Italian traditions modified by gradual and insensible

evolution into what has become an English style. For it is significant to

observe that in some cases, where a classical model has been too rigidly

followed, or its principles too closely adhered to, that the result is a thing

that remains exotic — that will not assimilate with the natural conditions of

our climate and landscape. What is right and fitting in Italy is not

necessarily right in England. The general principles may be imported, and may

grow into something absolutely right, but they cannot be compelled or coerced

into fitness, any more than we can take the myrtles and lentisks of the

Mediterranean region and expect them to grow on our middle-England hill-sides.

This is so much the case, with what one may call the temperament of a region

and climate, that even within the small geographical area of our islands, the comparative

suitability of the more distinctly Italian style may be clearly perceived, for

on our southern coasts it is much more possible than in the much colder and

bleaker midlands. Thus

we find that one of the best of the rather nearly Italian gardens is at

Brockenhurst in the New Forest, not far from the warm waters of the Solent. The

garden, in its present state, was laid out by the late Mr. John Morant, one of

a long line of the same name owning this forest property. He had absorbed the

spirit of the pure Italian gardens, and his fine taste knew how to bring it

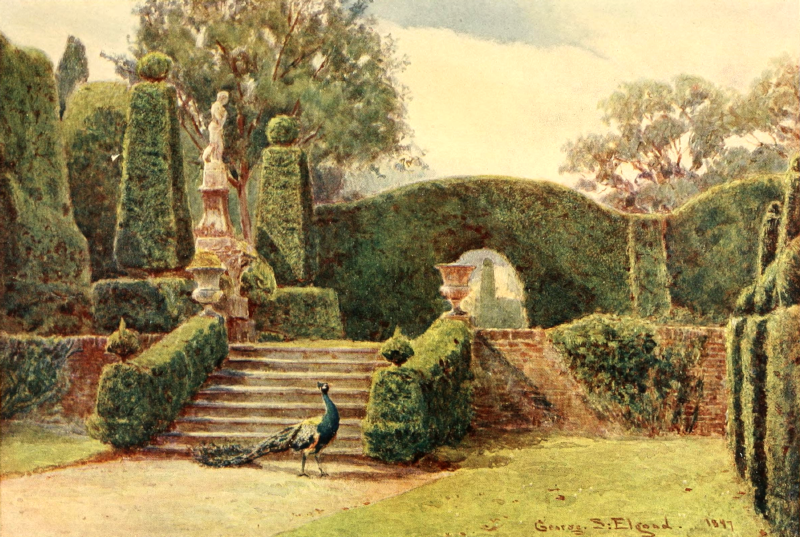

forth again, and place it with a sure hand on English soil. It is

none the less beautiful because it is a garden almost without flowers, so

important and satisfying are its permanent forms of living green walls, with

their own proper enrichment of ball and spire, bracket and buttress, and so

fine is the design of the actual masonry and sculpture. The

large rectangular pool, known as the Canal, bordered with a bold kerb, has at

its upper end a double stair-way; the retaining wall at the head of the basin

is cunningly wrought into buttress and niche. Every niche has it s appropriate

sculpture and each

buttress-pier its urn-like finial. On the upper level is a circular fountain

bordered by the same kerb in lesser proportion, with stone vases on its

circumference. The broad walk on both levels is bounded by close walls of

living greenery; on the upper level swinging round in a half circle, in which are

cut arched niches. In each leafy niche is a bust of a Caesar in marble on a

tall term-shaped pedestal. Orange trees in tubs stand by the sides of the

Canal. This is the most ornate portion of the garden, but its whole extent is

designed with equal care. There is a wide bowling-green for quiet play; turf

walks within walls of living green; everywhere that feeling of repose and ease

of mind and satisfaction that comes of good balance and proportion. It shows

the classical sentiment thoroughly assimilated, and a judicious interpretation

of it brought forth in a form not only possible but eminently successful, as a

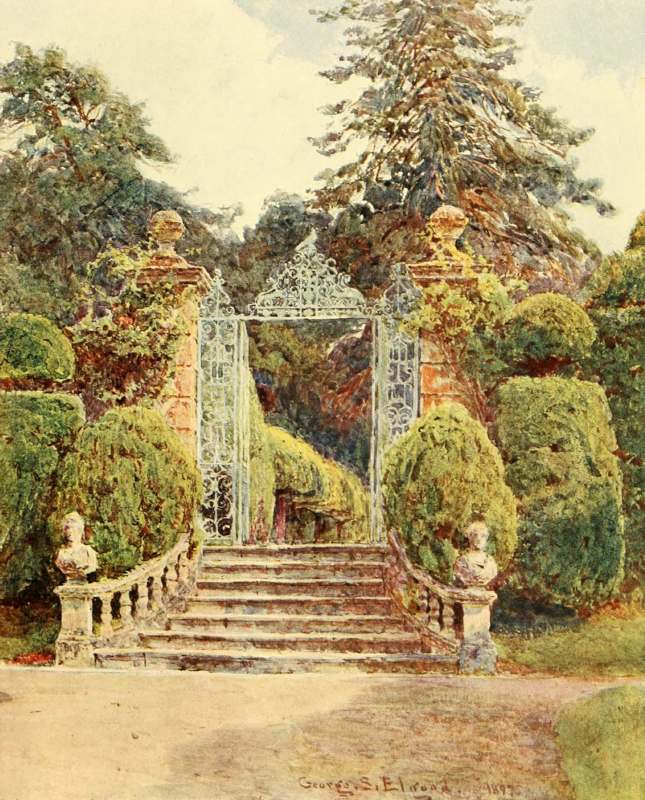

garden of Italy translated into the soil of one of our Southern Counties.  THE TERRACE, BROCKEN HURST From the picture in the possession of Mr. G. N. Stevens Whether

or not it is in itself the kind of gardening best suited for England may be

open to doubt, but at least it is the work of a man who knew what he wanted and

did it as well as it could possibly be done. Throughout it bears evidence of

the work of a master. There is no doubt, no ambiguity as to what is intended.

The strong will orders, the docile stone and vegetation obey. It is full-dress

gardening, stately, princely, full of dignity; gardening that has the courtly

sentiment. It seems to demand that the actual working of it should be kept out

of sight. Whereas in a homely garden it is pleasant to see people at work, and their

tools and implements ready to their hands, here there must be no visible

intrusion of wheelbarrow or shirt-sleeved labour. Possibly

the sentiment of a garden for state alone was the more gratifying to its owner

because of the near neighbourhood of miles upon miles of wild, free forest; land

of the same character being inclosed within the property; the tall trees

showing above the outer hedges and playing to the lightest airs of wind in an

almost strange contrast to the inflexible green boundaries of the ordered

garden. The

danger that awaits such a garden, now just coming to its early prime, is that

the careful hand should be relaxed. It is an heritage that carries with it much

responsibility; moreover, it would be ruined by the addition of any commonplace

gardening. Winter and summer it is nearly complete in itself; only in summer

flowers show as brilliant jewels in its marble vases and in its one restricted

parterre of box-edged beds. It is

a place whose design must always dominate the personal wishes, should they

desire other expression, of the succeeding owners. The borders of hardy and

half-hardy plants, that in nine gardens out of ten present the most obvious

ways of enjoying the beauty of flowers, are here out of place. In some rare

cases it might not be impossible to introduce some beautiful climbing plant or

plant of other habit, that would be in right harmony with the design, but it

should only be attempted by an artist who has such knowledge of, and sympathy

with, refined architecture as will be sure to guide him aright, and such a

consummate knowledge of plants as will at once present to his mind the identity

of the only possible plants that could so be used. Any mistaken choice or

introduction of unsuitable plants would grievously mar the design and would introduce

an element of jarring incongruity such as might easily be debased into

vulgarity. There

is no reason why such other gardening may not be rightly done even at

Brockenhurst, but it should not encroach upon or be mixed up with an Italian

design. Its place would be in quite another portion of the grounds. The

climate of North Lincolnshire is by no means one of the most favourable of our

islands, but the good gardener accepts the conditions of the place, faces the

obstacles, fights the difficulties, and conquers. Here

is a large walled garden, originally all kitchen garden; the length equal to

twice the breadth, divided in the middle to form two squares. It is further

subdivided in the usual manner with walks parallel to the walls, some ten feet

away from them, and other walks across and across each square. The paths are

box-edged and bordered on each side with fine groups of hardy flowers, such as

the Hollyhocks and other flowers in the picture.

From the picture in the possession of Miss Radcliffe |