| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2021 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

HARDWICK Hardwick

Hall in Derbyshire, one of the great houses of England, is, with others of its

approximate contemporaries of the later half of the sixteenth century, such as

Longleat, Wollaton, and Montacute, an example of what was at the time of its erection

an entirely new aspect of the possibilities of domestic architecture. The

country had settled down into a peaceful state. A house was no longer a castle

needing external defence. Hitherto the homes of England had been either

fortresses, or had needed the protection of moats and walls. They had been

poorly lighted; only the walls looking to an inner court, or to a small walled

garden could have fair-sized openings. No spacious windows could look abroad

upon open country, field or woodland. But by this time such restriction was a

thing of the past, and we see in these great houses, and in Hardwick

especially, immense window spaces in the outer walls. The architects of the

time, John Thorpe, the Smithsons and others, ran riot with their great windows,

as if revelling in their exemption from the older bonds. The new freedom was so

tempting that they knew not how to restrain themselves, and it was only later,

when it was found that the amount of lighting was overmuch for convenience,

that the relation of degree of light to internal comfort came to be better

understood and more reasonably adjusted. The

famous Countess of Shrewsbury (Bess of Hardwick), to whose initiative this

great house owes its origin, set an imperishable memorial of her imperious

arrogance upon the balustrading that crowns the square tower-like projections

at the angles and ends of the building, where the stone is wrought into lace-like fretwork of

arabesque, whereof the chief features are her coronet and the initials of her

name. A

spacious forecourt occupies the ground upon the western — the main entrance

front. It stretches the whole length of the house, and projects as much forward;

its outer sides being inclosed with a wall that bears in constant succession an

ornament of a fleur-de-lys with tall pyramidal top, a detail imported direct

from Italy, from the Renaissance gardens of earlier date. Such an ornament

occurs at the Villa d'Este at Tivoli, crowning a retaining wall. The entrance

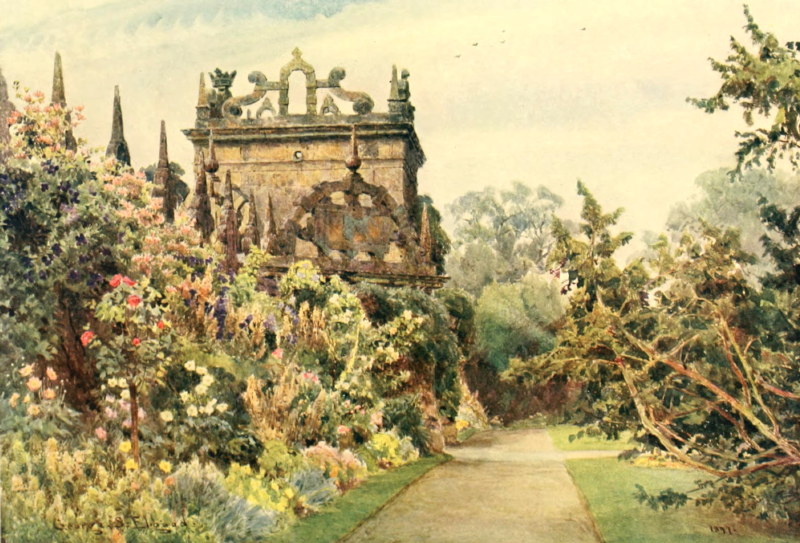

to the inclosed forecourt is by a handsome stone gateway. This gateway forms

the background of the picture, which shows one of the well-planted flower

borders that abound at Hardwick, and that strike that lightsome and cheerful

note of human care and delight that is so welcome in this place whose scale is rather

too large, and somewhat coldly forbidding, in relation to the more ordinary

aspects of daily comfort. Indeed

— for all the good planting — the long wall-backed flower border facing south,

whose wall is in part of its length that or the house itself, looks as if, in

relation to the great building towering above it — its occupants were still too

small, although they include flowering plants seven to nine feet high, such as

Gyneriums and the larger herbaceous Spiraeas. A well-directed effort has

evidently been made to have the planting on a scale with the lordly building,

but the items want to be larger still and the grouping yet bolder, to overcome

the dwarfing effect of the towering structure. In such a place the Magnolias,

both evergreen and deciduous, would have a fine effect, though possibly they

would hardly thrive in the midland climate. Within

the forecourt, along the wall parallel to the house and furthest from it, this need

is not so apparent. In the subject of the picture, the Honeysuckle, the

magnificently grown purple Clematis upon the wall, the Mulleins, Bocconia and

Japan Anemones, are in due proportion; the Tufted Pansies and Mignonette

bringing their taller brethren happily down to the grassy verge. Approaching

the pathway from the right, stretch

THE FORECOURT: HARDWICK From the picture in the possession of Mr. Aston Webb some

of the long loose growths of one of the two large Cedars that are such

prominent objects in the forecourt garden. The

main open spaces of this garden repeat in flower beds on grass the big E.S. of

the self-asserting founder. It is not pretty gardening nor particularly

dignified. No doubt it is only a modern acquiescence in the dominating

tradition of the place. Even making allowance for, and retaining this

sentiment, a better design might have been made, embodying these already

too-often-repeated letters. Moreover, the servile copying of the lettering in

its stone form only serves to illustrate the futility of reproducing a form of

ornament designed for one material in another of totally different nature. There

is some excellent gardening in a long flower-border outside the forecourt wall.

Here the size of the house is no longer oppressive, and it comes into proper

scale a little way beyond the point where the broad green ways, bounded by

noble hedges of ancient yews, swing into a wide circle as they cross, and show

the bold niches cut in the rich green foliage where leaden statues are so

effectively placed. By

the kindness of the owner, the Duke of Devonshire, Hardwick Hall, illustrating

as it does a distinct form of architectural expression with much of historical

interest, is open to the public. |