| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2021 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

PENSHURST

The

gardens that adorn the ancient home of the Sidneys are, as to the actual

planting of what we see to-day, with repairs to the house and some necessary

additions to fit it for modern needs, the work of the late Lord de L'Isle with

the architect George Devey, begun about fifty years ago. It was a time when

there was not much good work done in gardening, but both were men of fine taste

and ability, and the reparation and alteration needed for the house, and the

new planting and partly new designing of the garden could not have been in

better hands. The

aspect and sentiment of the garden, now that it has grown into shape — its

lines closely following, as far as it went, the old design — are in perfect accordance

with the whole feeling of the place, so that there seems to be no break in

continuity from the time of the original planting some centuries ago. Such as

it is to-day, such one feels sure it was in the old days — in parts line for

line and path for path, but throughout, just such a garden as to general form,

aspect, and above all, sentiment, as it must have been in the days of old. For

when it was first planted the conditions that would have to be considered were

always the same; requirement of shelter from prevailing winds; questions

relating to various portions, as to whether it would be desirable to welcome

the sunlight for the flowers' delight, or to shut it out for human enjoyment of

summer coolness — all such grounds of motive were, just as now, deliberated by the

men of old days, whose decisions, actuated by sympathy with both house and

ground, would bring forth a result whose character would be the same, whether

thought out and planned to-day or four centuries ago.  "GLOIRE DE DlJON," PENSHURST From the picture in the possession of Sir Reginald Hanson So it

is that we find the old work at Penshurst confirmed and renewed, and new work

added of a like kind, such as will make use of the wider modern range of garden

plants, while it retains the dignity and grandeur of the fine old place. The

house stands on a wide space of grass terrace commanding the garden. On a lower

level is a large quadrangular parterre, with cross paths. In each of its square

angles is a sunk garden with a five-foot-wide verge of turf and a bordering

stone kerb forming a step. The beds within, filled with good hardy plants, have

bold box edgings eighteen inches high and a foot thick, that not only set off

the bright masses of flowers within, but have in themselves an air of solidity

and importance that befits the large scale of the place. They represent in

their own position and on their lesser scale somewhat of the same character as

the massive yew hedges, twelve feet high and six feet through, that do their

own work in other parts of the garden. These

grand yew hedges and solid box borders have responded well to good planting and

tending, for the late Lord de L'Isle knew his work and did it thoroughly. Not

only was the ground well prepared, but for several years after planting the

young trees were provided with a surface dressing that prevented evaporation

and provided nutriment. This was carefully attended to, not only in the case of

the yews but of the box edgings also. The cross-walks

of the parterre do not meet in the middle, but sweep round a circular fountain

basin, in the centre of which stands a statue of what may be a young Hercules,

brought from Italy by Lord de L'Isle. The slender grace of the figure might at

first suggest a youthful Bacchus, but the identity in such a statue is easily

established by looking for one or other of the characteristic attributes of

Hercules; these usually are the lion's skin, the upright-growing hair on the

forehead, the poplar wreath or the battered, flattened ears. But the statue

stands too far from the walk to be exactly identified. That

the nearer portions of the garden are on the same lines as the older planting

is shown by an engraving in Harris's "Kent," where the parterre is, now

as then, bounded by terraces on two of its sides, the house side and that of

the adjoining churchyard, to which access is gained by a beautiful gabled

gateway of brick and stone, the work of Tudor times. The

old churchyard has its own beauty, while the church and a fine group of elms

are seen from the garden above the wall, and take their own beneficent place in

the garden landscape. The

rectangular fountain, which, with its surrounding yew hedges, and the grass

walks also inclosed by thick yew hedges, divides the two portions of the

kitchen garden, are also parts of the old design, added to by the late owner.

The yew hedges beyond the fountain pool have been set back to allow width

enough for a handsome flower-border on either side. Water Lilies grow in the

pool and the flower-borders display their beauties beyond, while the fruit

trees of the kitchen garden show above the thick green hedges as flowering

masses in spring, and in later summer, as the taller perennials of the border

rise to their full height, as a thin copse of fruit and leafage. The turf walk

and flower-border swing outward to suit the greater width of another

fountain-basin at the end. This has straight sides running the way of the main

path, and a segmental front. Instead of the usual rising kerb, there are two

shallow stone steps, the upper one even with the grass, the lower half way between

that and the water-level. Except that it is less of a protection than something

of the parapet kind, this is a most desirable means of near access to the water;

welcome to the eye in all ways and allowing the water-surface to be seen from a

distance. It is pleasantly noticeable in this pool that the water-level rises

to the proper place. Nothing is more frequent or more unsightly than a deep pool

or basin with straight sides and only a little water in the bottom. If the

height of the water is necessarily fluctuating it is a good plan to build the

tank in a succession of such steps; they are pleasant to see both above and under

water, and in the case of an accident to a straying child, danger is reduced to

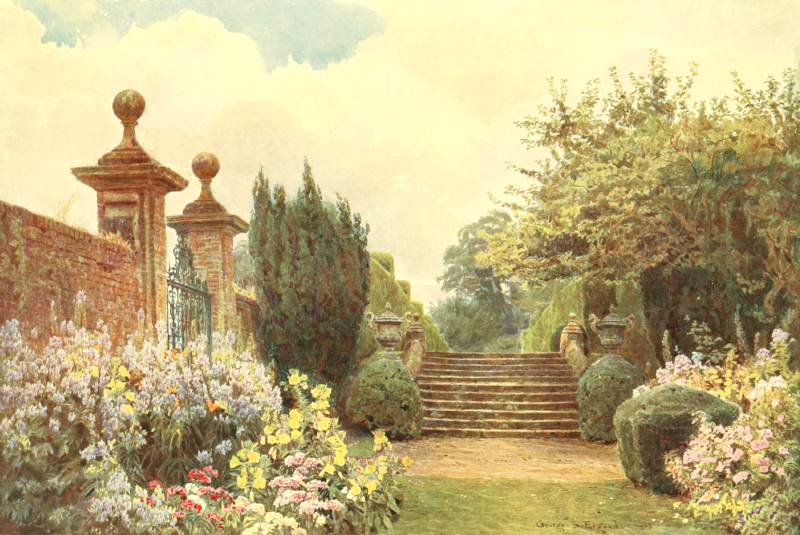

the smallest point.  THE TERRACE STEPS, PENSHURST From the picture in the possession of Mr. Frederick Greene The

picture shows one of the flights of steps from one level to another. To the

left two handsome gate-piers and a fine wrought-iron gate lead to a quiet green

meadow. Near by and just across it is the Medway, with wooded banks and groups

of fine trees. The old wall is beautiful from the meadow side; its coping

a garden of wild flowers. Above it is seen the clipped yew hedge with its

series of rising ornaments, rounded in the direction of the axis of the hedge,

but flat on its two faces. This is seen in the picture on the upper level,

above the steps to the left. Herbaceous

plants are grandly grown throughout this beautiful garden. Specially noticeable

are the fine taste and knowledge of garden effect with which they have been

used. There are not flowers everywhere, but between the flowery portions of the

garden are quiet green spaces that rest and refresh the eye, and that give both

eye and brain the best possible preparation for a further display and enjoyment

of their beauty. Such

an example the picture shows. On either side is a border with masses of

strong-growing hardy plants — pale Monkshood, Evening Primrose, Sweet-William,

Pink Mallow — then, above the steps, only the restful turf underfoot, and to

right and left the quiet walls of yew; at the end a group of great elms. At the

foot of the steps, passing away to the right, is another double flower-border,

passing again by a turn to the right into the quiet green walk leading to the

large fountain basin. Many

a good climbing Rose, with other rambling and clambering plants, find their

homes on the terraces. A Gloire de Dijon or one of its class — Madame Berard or

Bouquet d'Or, perhaps; either of these the equal of the other for such garden

use — rises from below the parapet of one of the flights of steps and comes

forward in happiest fellowship with a leaden vase of fine design; the dark

background of Irish Yew making the best possible ground for both Rose and urn. In

olden days these lead ornaments were commonly painted and gilt, but the revived

taste for all that is best in gardening rightly considers such treatment to be

a desecration of a surface which with age acquires a beautiful grey colouring

and a delightful quality of colour-texture. The painting of lead would seem to

be a relic of the many toy-like artifices in gardening that were prevalent in

Tudor times. All these are rejected in the best modern practice, though all the

old ways that made for true garden beauty and permanent growth and value have

been retained. A

clever way of utilising the stronger growing Clematises, including the large

purple Jackmanii, is here practised. They are swung garland-fashion between a

row of Apple-trees that borders one of the walks. Hops are used in the same

way. It was perhaps a remembrance of Italy, where Vines are trained to swing

between the Mulberries. The beautiful pale yellow Carnation, named Pride of Penshurst, was raised in this good garden, where everything tells of the truest sympathy with all that is best in English horticulture. Not the least among the soothing and satisfying influences of the pleasure-grounds of Penshurst, is the entire absence of the specimen conifer, that, with its wearisome repetition of single examples of young firs and pines, has brought such a displeasing element of restless confusion into so many pleasure-grounds. |