| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2021 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

AUTUMN

FLOWERS

How stout

and strong and full of well-being they are — the autumn flowers of our English

gardens! Hollyhocks, Tritomas, Sunflowers, Phloxes, among many others, and

lastly, Michaelmas Daisies. The flowers of the early year are lowly things,

though none the less lovable; Primroses, Double Daisies, Anemones, small

Irises, and all the beautiful host of small Squill and Snow-Glory and little

early Daffodils, Then come the taller Daffodils and Wallflowers, Tulips, and

the old garden Peonies and the lovely Tree Peonies. Then the true early summer

flowers. If

you notice, as the seasons progress, the average of the flowering plants

advances in stature. By June this average has risen again, with the Sea Hollies

and Flag Irises, the Chinese Peonies and the earlier Roses. And now there are

some quite tall things. Mulleins seven and eight feet high, some of them from

last year's seed, but the greater number from the seed-shedding of the year

before; the great white-leaved Mullein (Verboscum olympicum), taking four years

to come to flowering strength. But what a flower it is, when it is at last

thrown up! What a glorious candelabrum of branching bloom! Perhaps there is no

other hardy plant whose bulk of bloom on a single stem fills so large a space.

And what a grand effect it has when it is rightly planted; when its great

sulphur spire shows, half or wholly shaded, against the dusk of a wood edge or

in some sheltered bay, where garden is insensibly melting into woodland. This

is the place for these grand plants (for their flowers flag in hot sunshine),

in company with white Foxglove and the tall yellow Evening Primrose, another

tender bloom that is shy of sunlight. Four o'clock of a June morning is the

time to see these fine things at their best, when the birds are waking up, and

but for them the world is still, and the Cluster-Roses are opening their buds.

No one can know the whole beauty of a Cluster-Rose who has not seen it when the

summer day is quite young; when the buds of such a rose as the Garland have

just burst open and the sun has not yet bleached their wonderful tints of

shell-pink and tenderest shell-yellow into their only a little less beautiful

colouring of full midday. By

July there are still more of our tall garden flowers; the stately Delphiniums,

seven, eight, and nine feet high; tall white Lilies; the tall yellow

Meadow-Rues, Hollyhocks, and Sweet Peas in plenty. By

August we are in autumn; and it is the month of the tall Phloxes. There are

some who dislike the sweet, faint and yet strong scent of these flowers; to me

it is one of the delights of the flower year. No

garden flower has been more improved of late years; a whole new range of

excellent and brilliant colouring has been developed. I can remember when the

only Phloxes were a white and a poor Lilac; the individual flowers were small

and starry and set rather widely apart. They were straggly-looking things,

though always with the welcome sweet scent. Nowadays we all know the beauty of

these fine flowers; the large size of the massive heads and of the individual

blooms; the pure whites, the good Lilacs and Pinks, and that most desirable

range of salmon-rose colourings, of which one of the first that made a lively

stir in the world of horticulture was the one called Lothair. In its own colouring

of tender salmon-rose it is still one of the best. Careful seed-saving among

the brighter flowers of this colouring led to the tints tending towards

scarlet, among which Etna was a distinct advance, to be followed, a year or two

later, by the all-conquering Coquelicot. Some florists have also pushed this

docile flower into a range of colouring which is highly distasteful to the

trained colour-eye of the educated amateur; a series of rank purples and

virulent magentas; but these can be avoided. What is now most wanted, and seems

to be coming, is a range of tender, rather light Pinks, that shall have no

trace of the rank quality that seems so unwilling to leave the Phloxes of this

colouring. Garden

Phloxes were originally hybrids of two or three North American species; for

garden purposes they are divided into two groups, the earlier, blooming in

July, much shorter in stature and more bushy, being known as the suffruticosa

group, the later, taller kinds being classed as the decussata. They are a little

shy of direct sunlight, though they can bear it in strong soils where the roots

are always cool. They like plenty of food and moisture; in poor, dry, sandy

soils they fail absolutely, and even if watered and carefully watched, look

miserable objects. But

where Phloxes do well, and this is in most good garden ground, they are the

glory of the August flower-border. In

the teaching and practice of good gardening the fact can never be too

persistently urged nor too trustfully accepted, that the best effects are accomplished

by the simplest means. The garden artist or artist gardener is for ever

searching for these simple pictures; generally the happy combination of some

two kinds of flowers that bloom at the same time, and that make either kindly harmonies

or becoming contrasts. In

trying to work out beautiful garden effects, besides those purposely arranged,

it sometimes happens that some little accident — such as the dropping of a

seed, that has grown and bloomed where it was not sown — may suggest some

delightful combination unexpected and unthought of. At another time some small

spot of colour may be observed that will give the idea of the use of this

colour in some larger treatment. It is

just this self-education that is needed for the higher and more thoughtful

gardening, whose outcome is the simply conceived and beautiful pictures,

whether they are pictures painted with the brush on paper or canvas, or with

living plants in the open ground. In both cases it needs alike the training of

the eye to observe, of the brain to note, and of the hand to work out the

interpretation.

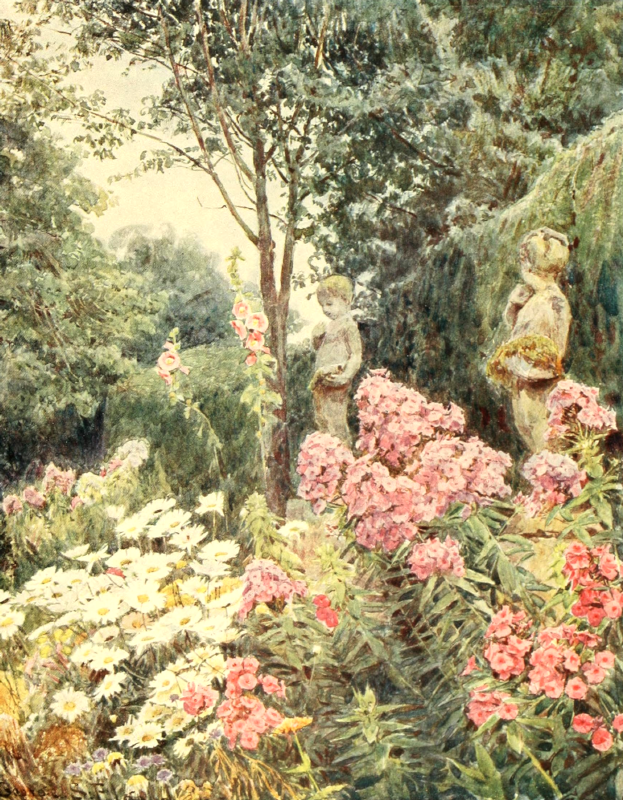

PHLOX AND DAISY From the picture in the possession of Lady Mount-Stephen The

garden artist — by which is to be understood the true lover

of good flowers, who has taken the trouble to learn their ways and wants and moods,

and to know it all so surely that he can plant with the assured belief that the

plants he sets will do as he intends, just as the painter can compel and

command the colours on his palette — plants with an unerring hand and awaits

the sure result. When

one says "the simplest means," it does not always mean the easiest.

Many people begin their gardening by thinking that the making and maintaining

of a handsome and well-filled flower-border is quite an easy matter. In fact,

it is one of the most difficult problems in the whole range of horticultural

practice — wild gardening perhaps excepted. To achieve anything beyond the

ordinary commonplace mixture, that is without plan or forethought, and that

glares with the usual faults of bad colour-combinations and yawning, empty

gaps, needs years of observation and a considerable knowledge of plants and

their ways as individuals. For

border plants to be at their best must receive special consideration as to

their many and different wants. We have to remember that they are gathered

together in our gardens from all the temperate regions of the world, and from

every kind of soil and situation. From the sub-arctic regions of Siberia to the

very edges of the Sahara; from the cool and ever-moist flanks of the Alps to

the sun-dried coasts of the Mediterranean; from the Cape, from the great

mountain ranges of India; from the cool and temperate Northern States of

America — the home of the species from which our garden Phloxes are derived; from

the sultry slopes of Chili and Peru, where the Alströmerias thrust their roots

deep down into the earth searching for the precious moisture. So it

is that as our garden flowers come to us from many climes and many soils, we

have to bear in mind the nature of their places of origin the better to be

prepared to give them suitable treatment. We have to know, for instance, which

are the few plants that will endure drought and a poor, hot soil; for the

greater number abhor it; and yet such places occur in some gardens and have to

be provided with what is suitable. Then we have to know which are those that

will only come to their best in a rich loam, and that the Phloxes are among

these, and the Roses; and which are the plants and shrubs that must have Ume,

or at least must have it if they are to do their very best. Such are the

Clematises and many of the lovely little alpines; while to some other plants,

many of the alpines that grow on the granite, and nearly all the Rhododendrons,

lime is absolute poison; for, entering the system and being drawn up into the circulation, it clogs and bursts their tiny

veins; the leaves turn yellow, the plant dies, or only survives in a miserably

crippled state. An

experienced gardener, if he were blindfolded, and his eyes uncovered in an

unknown garden whose growths left no soil visible, could tell its nature by

merely seeing the plants and observing their relative well-being, just as,

passing by rail or road through an unfamiliar district, he would know by the

identity and growth of the wild plants and trees what was the nature of the

soil beneath them. The

picture, then, showing autumn Phloxes grandly grown, tells of good gardening

and of a strong, rich loamy soil. This is also proved by the height of the

Daisies [Chrysanthemum maximum). But the lesson the picture so pleasantly

teaches is above all to know the merit of one simple thing well done. Two

charming little stone figures of amorini

stand up on their plinths among the flowers; the boy figure holds a bird's

nest, his girl companion a shell. They are of a pattern not unfrequent in English

gardens, and delightfully in sympathy with our truest home flowers. The quiet

background of evergreen hedge admirably suits both figures and flowers. It is

all quite simple — just exactly right. Daisies — always the children's flowers,

and, with them, another of wide-eyed innocence, of dainty scent, of tender

colouring. Quite simple and just right; but then — it is in the artist's own

garden. |