VII

kut,

discovering that the boy was not close behind him, turned back to

search for him. He had gone but a short distance in return when he

was brought to a sudden and startled halt by sight of a strange

figure moving through the trees toward him. It was the boy, yet could

it be? In his hand was a long spear, down his back hung an oblong

shield such as the black warriors who had attacked them had worn, and

upon ankle and arm were bands of iron and brass, while a loin cloth

was twisted about the youth's middle. A knife was thrust through its

folds. kut,

discovering that the boy was not close behind him, turned back to

search for him. He had gone but a short distance in return when he

was brought to a sudden and startled halt by sight of a strange

figure moving through the trees toward him. It was the boy, yet could

it be? In his hand was a long spear, down his back hung an oblong

shield such as the black warriors who had attacked them had worn, and

upon ankle and arm were bands of iron and brass, while a loin cloth

was twisted about the youth's middle. A knife was thrust through its

folds.

When

the boy saw the ape he hastened forward to exhibit his trophies.

Proudly he called attention to each of his newly won possessions.

Boastfully he recounted the details of his exploit.

"With

my bare hands and my teeth I killed him," he said. "I would

have made friends with them but they chose to be my enemies. And now

that I have a spear I shall show Numa, too, what it means to have me

for a foe. Only the white men and the great apes, Akut, are our

friends. Them we shall seek, all others must we avoid or kill. This

have I learned of the jungle."

They

made a detour about the hostile village, and resumed their journey

toward the coast. The boy took much pride in his new weapons and

ornaments. He practiced continually with the spear, throwing it at

some object ahead hour by hour as they traveled their loitering way,

until he gained a proficiency such as only youthful muscles may

attain to speedily. All the while his training went on under the

guidance of Akut. No longer was there a single jungle spoor but was

an open book to the keen eyes of the lad, and those other indefinite

spoor that elude the senses of civilized man and are only partially

appreciable to his savage cousin came to be familiar friends of the

eager boy. He could differentiate the innumerable species of the

herbivora by scent, and he could tell, too, whether an animal was

approaching or departing merely by the waxing or waning strength of

its effluvium. Nor did he need the evidence of his eyes to tell him

whether there were two lions or four up wind, — a hundred yards

away or half a mile.

Much

of this had Akut taught him, but far more was instinctive knowledge —

a species of strange intuition inherited from his father. He had come

to love the jungle life. The constant battle of wits and senses

against the many deadly foes that lurked by day and by night along

the pathway of the wary and the unwary appealed to the spirit of

adventure which breathes strong in the heart of every red-blooded son

of primordial Adam. Yet, though he loved it, he had not let his

selfish desires outweigh the sense of duty that had brought him to a

realization of the moral wrong which lay beneath the adventurous

escapade that had brought him to Africa. His love of father and

mother was strong within him, too strong to permit unalloyed

happiness which was undoubtedly causing them days of sorrow. And so

he held tight to his determination to find a port upon the coast

where he might communicate with them and receive funds for his return

to London. There he felt sure that he could now persuade his parents

to let him spend at least a portion of his time upon those African

estates which from little careless remarks dropped at home he knew

his father possessed. That would be something, better at least than a

lifetime of the cramped and cloying restrictions of civilization. Much

of this had Akut taught him, but far more was instinctive knowledge —

a species of strange intuition inherited from his father. He had come

to love the jungle life. The constant battle of wits and senses

against the many deadly foes that lurked by day and by night along

the pathway of the wary and the unwary appealed to the spirit of

adventure which breathes strong in the heart of every red-blooded son

of primordial Adam. Yet, though he loved it, he had not let his

selfish desires outweigh the sense of duty that had brought him to a

realization of the moral wrong which lay beneath the adventurous

escapade that had brought him to Africa. His love of father and

mother was strong within him, too strong to permit unalloyed

happiness which was undoubtedly causing them days of sorrow. And so

he held tight to his determination to find a port upon the coast

where he might communicate with them and receive funds for his return

to London. There he felt sure that he could now persuade his parents

to let him spend at least a portion of his time upon those African

estates which from little careless remarks dropped at home he knew

his father possessed. That would be something, better at least than a

lifetime of the cramped and cloying restrictions of civilization.

And

so he was rather contented than otherwise as he made his way in the

direction of the coast, for while he enjoyed the liberty and the

savage pleasures of the wild his conscience was at the same time

clear, for he knew that he was doing all that lay in his power to

return to his parents. He rather looked forward, too, to meeting

white men again — creatures of his own kind — for there had been

many occasions upon which he had longed for other companionship than

that of the old ape. The affair with the blacks still rankled in his

heart. He had approached them in such innocent good fellowship and

with such childlike assurance of a hospitable welcome that the

reception which had been accorded him had proved a shock to his

boyish ideals. He no longer looked upon the black man as his brother;

but rather as only another of the innumerable foes of the

bloodthirsty jungle — a beast of prey which walked upon two feet

instead of four.

But

if the blacks were his enemies there were those in the world who were

not. There were those who always would welcome him with open arms;

who would accept him as a friend and brother, and with whom he might

find sanctuary from every enemy. Yes, there were always white men.

Somewhere along the coast or even in the depths of the jungle itself

there were white men. To them he would be a welcome visitor. They

would befriend him. And there were also the great apes — the

friends of his father and of Akut. How glad they would be to receive

the son of Tarzan of the Apes! He hoped that he could come upon them

before he found a trading post upon the coast. He wanted to be able

to tell his father that he had known his old friends of the jungle,

that he had hunted with them, that he had joined with them in their

savage life, and their fierce, primeval ceremonies — the strange

ceremonies of which Akut had tried to tell him. It cheered him

immensely to dwell upon these happy meetings. Often he rehearsed the

long speech which he would make to the apes, in which he would tell

them of the life of their former king since he had left them.

At

other times he would play at meeting with white men. Then he would

enjoy their consternation at sight of a naked white boy trapped in

the war togs of a black warrior and roaming the jungle with only a

great ape as his companion.

And

so the days passed, and with the traveling and the hunting and the

climbing the boy's muscles developed and his agility increased until

even phlegmatic Akut marvelled at the prowess of his pupil. And the

boy, realizing his great strength and revelling in it, became

careless. He strode through the jungle, his proud head erect, defying

danger. Where Akut took to the trees at the first scent of Numa, the

lad laughed in the face of the king of beasts and walked boldly past

him. Good fortune was with him for a long time. The lions he met were

well-fed, perhaps, or the very boldness of the strange creature which

invaded their domain so filled them with surprise that thoughts of

attack were banished from their minds as they stood, round-eyed,

watching his approach and his departure. Whatever the cause, however,

the fact remains that on many occasions the boy passed within a few

paces of some great lion without arousing more than a warning growl.

But

no two lions are necessarily alike in character or temper. They

differ as greatly as do individuals of the human family. Because ten

lions act similarly under similar conditions one cannot say that the

eleventh lion will do likewise — the chances are that he will not.

The lion is a creature of high nervous development. He thinks,

therefore he reasons. Having a nervous system and brains he is the

possessor of temperament, which is affected variously by extraneous

causes. One day the boy met the eleventh lion. The former was walking

across a small plain upon which grew little clumps of bushes. Akut

was a few yards to the left of the lad who was the first to discover

the presence of Numa.

"Run,

Akut," called the boy, laughing. "Numa lies hid in the

bushes to my right. Take to the trees. Akut! I, the son of Tarzan,

will protect you," and the boy, laughing, kept straight along

his way which led close beside the brush in which Numa lay concealed.

The

ape shouted to him to come away, but the lad only flourished his

spear and executed an improvised war dance to show his contempt for

the king of beasts. Closer and closer to the dread destroyer he came,

until, with a sudden, angry growl, the lion rose from his bed not ten

paces from the youth. A huge fellow he was, this lord of the jungle

and the desert. A shaggy mane clothed his shoulders. Cruel fangs

armed his great jaws. His yellow-green eyes blazed with hatred and

challenge.

The

boy, with his pitifully inadequate spear ready in his hand, realized

quickly that this lion was different from the others he had met; but

he had gone too far now to retreat. The nearest tree lay several

yards to his left — the lion could be upon him before he had

covered half the distance, and that the beast intended to charge none

could doubt who looked upon him now. Beyond the lion was a thorn tree

— only a few feet beyond him. It was the nearest sanctuary but Numa

stood between it and his prey.

The

feel of the long spear shaft in his hand and the sight of the tree

beyond the lion gave the lad an idea — a preposterous idea — a

ridiculous, forlorn hope of an idea; but there was no time now to

weigh chances — there was but a single chance, and that was the

thorn tree. If the lion charged it would be too late — the lad must

charge first, and to the astonishment of Akut and none the less of

Numa, the boy leaped swiftly toward the beast. Just for a second was

the lion motionless with surprise and in that second Jack Clayton put

to the crucial test an accomplishment which he had practiced at

school.

Straight

for the savage brute he ran, his spear held butt foremost across his

body. Akut shrieked in terror and amazement. The lion stood with

wide, round eyes awaiting the attack, ready to rear upon his hind

feet and receive this rash creature with blows that could crush the

skull of a buffalo.

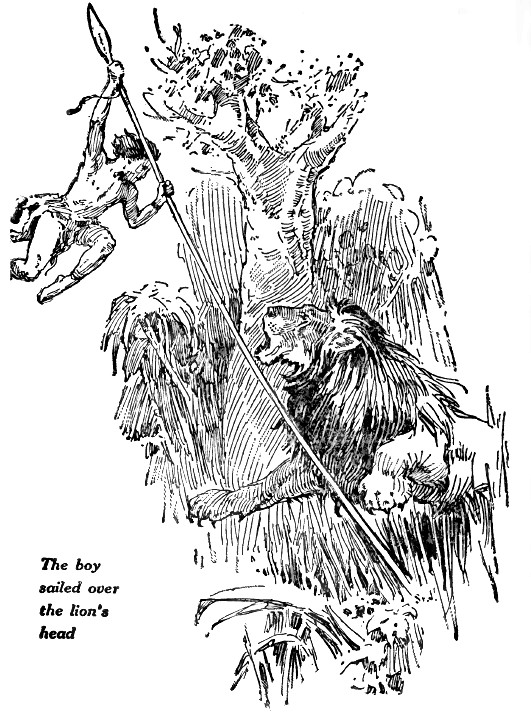

Just

in front of the lion the boy placed the butt of his spear upon the

ground, gave a mighty spring, and, before the bewildered beast could

guess the trick that had been played upon him, sailed over the lion's

head into the rending embrace of the thorn tree — safe but

lacerated.

Akut

had never before seen a pole-vault. Now he leaped up and down within

the safety of his own tree, screaming taunts and boasts at the

discomfited Numa, while the boy, torn and bleeding, sought some

position in his thorny retreat in which he might find the least

agony. He had saved his life; but at considerable cost in suffering.

It seemed to him that the lion would never leave, and it was a full

hour before the angry brute gave up his vigil and strode majestically

away across the plain. When he was at a safe distance the boy

extricated himself from the thorn tree; but not without inflicting

new wounds upon his already tortured flesh.

It

was many days before the outward evidence of the lesson he had

learned had left him; while the impression upon his mind was one that

was to remain with him for life. Never again did he uselessly tempt

fate.

He

took long chances often in his after life; but only when the taking

of chances might further the attainment of some cherished end —

and, always thereafter, he practiced pole-vaulting.

For

several days the boy and the ape lay up while the former recovered

from the painful wounds inflicted by the sharp thorns. The great

anthropoid licked the wounds of his human friend, nor, aside from

this, did they receive other treatment, but they soon healed, for

healthy flesh quickly replaces itself.

When

the lad felt fit again the two continued their journey toward the

coast, and once more the boy's mind was filled with pleasurable

anticipation.

And

at last the much dreamed of moment came. They were passing through a

tangled forest when the boy's sharp eyes discovered from the lower

branches through which he was traveling an old but well-marked spoor

— a spoor that set his heart to leaping — the spoor of man, of

white men, for among the prints of naked feet were the well defined

outlines of European made boots. The trail, which marked the passage

of a good-sized company, pointed north at right angles to the course

the boy and the ape were taking toward the coast.

Doubtless

these white men knew the nearest coast settlement. They might even be

headed for it now. At any rate it would be worth while overtaking

them if even only for the pleasure of meeting again creatures of his

own kind. The lad was all excitement; palpitant with eagerness to be

off in pursuit. Akut demurred. He wanted nothing of men. To him the

lad was a fellow ape, for he was the son of the king of apes. He

tried to dissuade the boy, telling him that soon they should come

upon a tribe of their own folk where some day when he was older the

boy should be king as his father had before him. But Jack was

obdurate. He insisted that he wanted to see white men again. He

wanted to send a message to his parents. Akut listened and as he

listened the intuition of the beast suggested the truth to him —

the boy was planning to return to his own kind.

The

thought filled the old ape with sorrow. He loved the boy as he had

loved the father, with the loyalty and faithfulness of a hound for

its master. In his ape brain and his ape heart he had nursed the hope

that he and the lad would never be separated. He saw all his fondly

cherished plans fading away, and yet he remained loyal to the lad and

to his wishes. Though disconsolate he gave in to the boy's

determination to pursue the safari of the white men, accompanying him

upon what he believed would be their last journey together.

The

spoor was but a couple of days old when the two discovered it, which

meant that the slow-moving caravan was but a few hours distant from

them whose trained and agile muscles could carry their bodies swiftly

through the branches above the tangled undergrowth which had impeded

the progress of the laden carriers of the white men.

The

boy was in the lead, excitement and anticipation carrying him ahead

of his companion to whom the attainment of their goal meant only

sorrow. And it was the boy who first saw the rear guard of the

caravan and the white men he had been so anxious to overtake.

Stumbling

along the tangled trail of those ahead a dozen heavily laden blacks

who, from fatigue or sickness, had dropped behind were being prodded

by the black soldiers of the rear guard, kicked when they fell, and

then roughly jerked to their feet and hustled onward. On either side

walked a giant white man, heavy blonde beards almost obliterating

their countenances. The boy's lips formed a glad cry of salutation as

his eyes first discovered the whites — a cry that was never

uttered, for almost immediately he witnessed that which turned his

happiness to anger as he saw that both the white men were wielding

heavy whips brutally upon the naked backs of the poor devils

staggering along beneath loads that would have overtaxed the strength

and endurance of strong men at the beginning of a new day.

Every

now and then the rear guard and the white men cast apprehensive

glances rearward as though momentarily expecting the materialization

of some long expected danger from that quarter. The boy had paused

after his first sight of the caravan, and now was following slowly in

the wake of the sordid, brutal spectacle. Presently Akut came up with

him. To the beast there was less of horror in the sight than to the

lad, yet even the great ape growled beneath his breath at useless

torture being inflicted upon the helpless slaves. He looked at the

boy. Now that he had caught up with the creatures of his own kind,

why was it that he did not rush forward and greet them? He put the

question to his companion.

"They

are fiends," muttered the boy. "I would not travel with

such as they, for if I did I should set upon them and kill them the

first time they beat their people as they are beating them now; but,"

he added, after a moment's thought, "I can ask them the

whereabouts of the nearest port, and then, Akut, we can leave them."

The

ape made no reply, and the boy swung to the ground and started at a

brisk walk toward the safari. He was a hundred yards away, perhaps,

when one of the whites caught sight of him. The man gave a shout of

alarm, instantly levelling his rifle upon the boy and firing. The

bullet struck just in front of its mark, scattering turf and fallen

leaves against the lad's legs. A second later the other white and the

black soldiers of the rear guard were firing hysterically at the boy.

Jack

leaped behind a tree, unhit. Days of panic ridden flight through the

jungle had filled Carl Jenssen and Sven Malbihn with jangling nerves

and their native boys with unreasoning terror. Every new note from

behind sounded to their frightened ears the coming of The Sheik and

his bloodthirsty entourage. They were in a blue funk, and the sight

of the naked white warrior stepping silently out of the jungle

through which they had just passed had been sufficient shock to let

loose in action all the pent nerve energy of Malbihn, who had been

the first to see the strange apparition. And Malbihn's shout and shot

had set the others going.

When

their nervous energy had spent itself and they came to take stock of

what they had been fighting it developed that Malbihn alone had seen

anything clearly. Several of the blacks averred that they too had

obtained a good view of the creature but their descriptions of it

varied so greatly that Jenssen, who had seen nothing himself, was

inclined to be a trifle skeptical. One of the blacks insisted that

the thing had been eleven feet tall, with a man's body and the head

of an elephant. Another had seen three

immense Arabs with huge, black

beards; but when, after conquering their nervousness, the rear guard

advanced upon the enemy's position to investigate they found nothing,

for Akut and the boy had retreated out of range of the unfriendly

guns.

Jack

was disheartened and sad. He had not entirely recovered from the

depressing effect of the unfriendly reception he had received at the

hands of the blacks, and now he had found an even more hostile one

accorded him by men of his own color.

"The

lesser beasts flee from me in terror," he murmured, half to

himself, "the greater beasts are ready to tear me to pieces at

sight. Black men would kill me with their spears or arrows. And now

white men, men of my own kind, have fired upon me and driven me away.

Are all the creatures of the world my enemies? Has the son of Tarzan

no friend other than Akut?"

The

old ape drew closer to the boy.

"There

are the great apes," he said. "They only will be the

friends of Akut's friend. Only the great apes will welcome the son of

Tarzan. You have seen that men want nothing of you. Let us go now and

continue our search for the great apes — our people."

The

language of the great apes is a combination of monosyllabic

gutturals, amplified by gestures and signs. It may not be literally

translated into human speech; but as near as may be this is what Akut

said to the boy.

The

two proceeded in silence for some time after Akut had spoken. The boy

was immersed in deep thought — bitter thoughts in which hatred and

revenge predominated. Finally he spoke: "Very well, Akut,"

he said, "we will find our friends, the great apes."

The

anthropoid was overjoyed; but he gave no outward demonstration of his

pleasure. A low grunt was his only response, and a moment later he

had leaped nimbly upon a small and unwary rodent that had been

surprised at a fatal distance from its burrow. Tearing the unhappy

creature in two Akut handed the lion's share to the lad.

|