|

Wallpaper Images |

Nekrassoff |

Web Text-ures© |

Guide to |

Our Cats' |

|---|

|

Wallpaper Images |

Nekrassoff |

Web Text-ures© |

Guide to |

Our Cats' |

|---|

THE MODERN STEERAGE

BY

The World Today - June 1904.

OW fares it

with the steerage passenger to-day? Does he suffer from overcrowding, lack

of fresh air, food, water, and reasonably healthy surroundings? It was to

find an answer to such questions that I shipped as an ordinary steerage

passenger on the largest liner afloat, the “Cedric,” 21,-000 tons, newly built

and presumably modern in every way; and this is what I found. It is a story

of conditions on the largest of the new ships. What might happen on one of the

little old ones still in the service is, perhaps, another question. Now it is

not so easy a matter as one might think to ship as a third-class passenger. At

the ticket office you have to give an account of yourself, tell who you are,

whence you come, whither you intend to go, your age, whether married or

single, your occupation, whether an anarchist or not; and in accordance with

your answers you are pretty carefully scrutinized and sized up by the

emigration authorities. Then there are the doctors to pass, in itself no

slight ordeal, for the physician of the emigration board inspects you and

passes you over to the ship’s doctor. If either sees signs of ill-health you

are sent to an inner room and held for a further, far more rigid, examination;

and unless this shows you sound and whole the bars are down against you. You

may have bought your ticket in Poland or Norway or southern Italy, and

traveled far already to the dock. That does not matter. Clean and whole in

body, mind and record you must be or the ship sails without you. Of course

this rigor works hardship in many cases. Never a ship leaves the Liverpool

landing stage but the unfit, held back by the inexorable arm of the law, see

it depart through blinding tears of disappointment and misery. Back to the

home land these must go to suffer as they may. The new world will have none of

them.

OW fares it

with the steerage passenger to-day? Does he suffer from overcrowding, lack

of fresh air, food, water, and reasonably healthy surroundings? It was to

find an answer to such questions that I shipped as an ordinary steerage

passenger on the largest liner afloat, the “Cedric,” 21,-000 tons, newly built

and presumably modern in every way; and this is what I found. It is a story

of conditions on the largest of the new ships. What might happen on one of the

little old ones still in the service is, perhaps, another question. Now it is

not so easy a matter as one might think to ship as a third-class passenger. At

the ticket office you have to give an account of yourself, tell who you are,

whence you come, whither you intend to go, your age, whether married or

single, your occupation, whether an anarchist or not; and in accordance with

your answers you are pretty carefully scrutinized and sized up by the

emigration authorities. Then there are the doctors to pass, in itself no

slight ordeal, for the physician of the emigration board inspects you and

passes you over to the ship’s doctor. If either sees signs of ill-health you

are sent to an inner room and held for a further, far more rigid, examination;

and unless this shows you sound and whole the bars are down against you. You

may have bought your ticket in Poland or Norway or southern Italy, and

traveled far already to the dock. That does not matter. Clean and whole in

body, mind and record you must be or the ship sails without you. Of course

this rigor works hardship in many cases. Never a ship leaves the Liverpool

landing stage but the unfit, held back by the inexorable arm of the law, see

it depart through blinding tears of disappointment and misery. Back to the

home land these must go to suffer as they may. The new world will have none of

them.

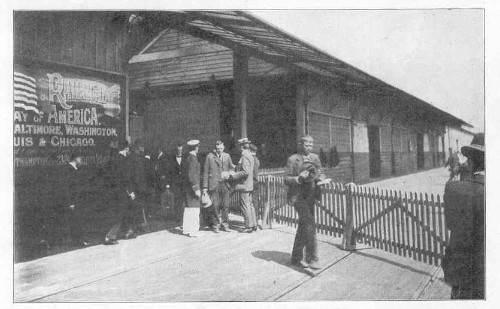

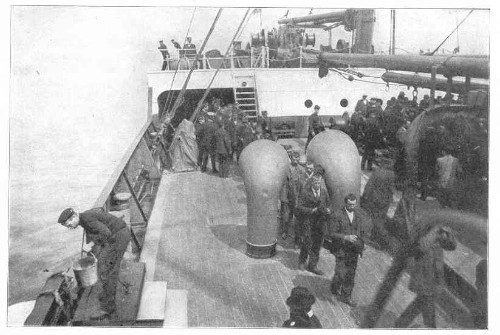

There were about fourteen hundred of us, all told, who were hustled aboard the tender in the early morning. We went up the narrow gangway in a tumultuous stream. There was jostling and laughter and the jargon of strange tongues. The bulk of the crowd were Scandinavians, lean, yellow-haired giants from the fjords of Norway or the villages about the northern shore of the Baltic. There were also Belgians and Dutch, Bohemians and Poles, a hundred or so of English and quite a few Italians, all gathered from many fishing grounds by the nets of the steamship agents, to be finally impounded on the “Cedric.” On boarding the tender we gave up a coupon, on the steamer’s deck the balance of a big poster, printed in red and black. Immediately there was a rude classification and separation managed by energetic and vociferous steerage stewards, the single men being sent forward, so far as possible, the single women aft, while families were located amidships.

|

That is the end of the introduction to the vessel. After that you go below for the first time and, if you are shrewd, you soon see that there is variety in the quarters assigned to the third class. The single men found themselves steered to large rooms forward, two or three decks down, where there were very many gas-pipe bunks in tiers, each containing a mattress and two big blankets. Under these bunks they stored their hand-bags and took possession, one each until a hundred or more were thus accommodated in a room. These rooms are kept clean during the trip by the heroic efforts of the sixty steerage stewards, who swept and washed and disinfected by day and by night. Streams of fresh air swept down into them continually from the deck ventilators, and, in spite of their dense population, the sanitary conditions were good.

But there were better accommodations than these. Amidships and aft were many steerage staterooms, containing two to eight berths, largely taken up by families and groups of the single women. Each of these contained a seat hinged to the wall, a little mirror, an electric light, but they were otherwise without furniture, except for bedding in the bunks similar to that in the large rooms. They were as scrupulously clean and neat as white paint and soap and water could make them. The stewards in charge of these rooms saw that they were kept neat, and like the first-class stewards were remarkably accommodating. I was in luck enough to get one of these rooms with only two berths, and, as it fortunately came about, I had it all to myself. I had a good mattress, sheets and a pillow. The expense of all this, including some little extra attentions for which I paid a very moderate fee, was very little and I began to perceive that a wise man may travel third-class and not suffer, provided he has a few extra dollars in his pocket.

|

Many, particularly from among the Scandinavians, though they were steered to the larger rooms, were not long in finding out that there were more desirable ones and they came down amidships to occupy such as they could get. When ordered out they took refuge in a seeming stolidity and lack of knowledge of English that nothing could move. A few thus retained the better berths, eluding the stewards who had to haul them out by main strength. The stewards I found to be tactful and discriminating in this matter. Many of the English emigrants were people of considerable refinement and a good sort. Some were Canadians returning from the Boer war. These, their English fellow countrymen, the stewards, seemed to favor in matters of personal attention. Blood will tell, even in the hurly burly of settling 1,400 emigrants aboard an ocean liner. Much of this arranging and settling took place while the “Cedric” swung in mid-stream on the morning of the sailing day, the details lasting several days longer, especially in the matter of ousting the stolid Scandinavian freebooters from their pirated vantage. All was finally settled, generously and tactfully, and without bludgeoning or bluster.

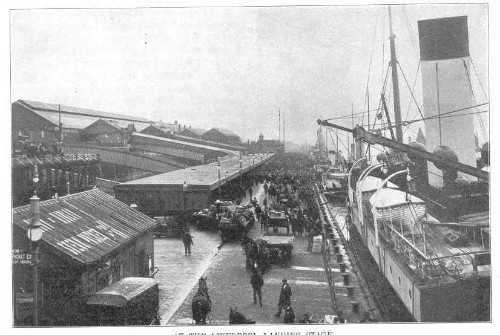

At noon the boat swung alongside the landing stage. Everybody rushed upon deck to see the first-class passengers arrive, to bid good-by to friends if one had any, and to see the last of the city in any case. The great floating stage is a thousand feet long and it was black with people. It must needs be buoyant for it holds up the sorrow of the world. The silent, swift river that flows beneath runs salt to the sea from the parting tears that are shed on it. The steamer’s open deck was solid with a writhing mass of humanity. Laughter and jeers were the portion of many, wet cheeks and the wringing of hands that of others, while others still stood silent in the dumb desolation that is most pathetic of all. Only the English, Welsh and Irish who shipped at Liverpool had friends on the stage. Ole and Hans, Pietro and Ivan, had said good-by in the home land, days before. To them the scene was hut one of curious interest.

At the rail a dozen Welshmen stood singing a folk-song of their own land in a doleful minor. They seemed to feel sad, for, as they sang, the tears stood on their cheeks. On the stage their friends shouted farewells and encouragement to them with laughter that broke in sobs. During the hours that the ship loomed above the stage they sang, and the minor wail cropped out at intervals for days after the ship was at sea. The gangplank was taken in, the tugs drew alongside, so far below that you could look down into their stacks, the great whistle roared in a prolonged farewell, and we were off. A shout went up from deck and dock, and through it all thrilled a thin cry of anguish. A little freckle-faced Irish lass was struggling at the rail. “Aw, me mither, me mither!” she wailed, and reached her hands in longing toward the stage where in the jostling crowd a stout old lady had fainted in grief at losing her colleen. An older woman slipped her arm about the little lass and comforted her as best she might, while the faces of all within sight of the group grew sad in sympathy.

|

But such scenes are few. To the bulk of the crowd the departure was but one more scene in a great picnic. Once the ship had started excitement buoyed them up and made them hilarious. They chatted, one with another, in many tongues, joked and skylarked, and moved ever restlessly about. New acquaintances were easily made, and, as the ship moved in stately fashion down the Mersey, all was bustle and animation. About this time I went below to stand guard over my stateroom. The average European emigrant is neither alert nor particularly resourceful, but he is cheeky and persistent — so, at least I found him on the “Cedric” — and though my friend, the steward, would no doubt have driven out intruders in the end, I felt it wiser to prevent invasion. The room could be barred with a hook on the inside, but there was neither lock nor key. When you went out you left it open to whoever might come.

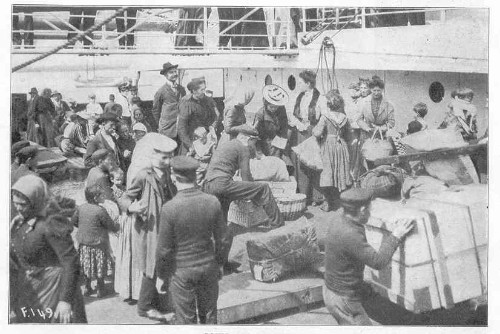

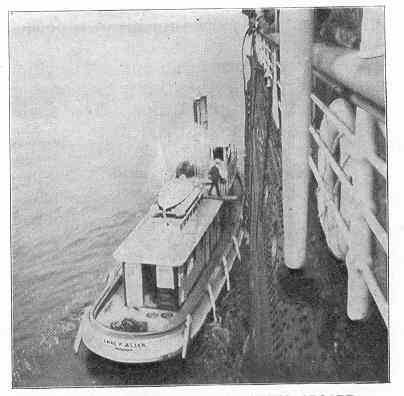

This was a Friday, the White Star sailing day from Liverpool. Saturday morning we were at anchor in Queenstown harbor and received another instalment of emigrants, several hundred Irish. Whatever may have been their sorrows of parting I do not know, but certainly no more hilarious crowd ever boarded an ocean liner. The two little tenders were black with people, and when they climbed the slender gangway from the top of the tender to the deck of the “Cedric” the leaven of liveliness began to work in the whole stolid 1,400 already there. Every lad seemed to have his lass, and the courting was fast and furious, and from the start, undismayed by the surrounding crowd.

|

With the tenders came the bumboat women, drawing alongside in nondescript small craft. For these there was neither rope ladder nor gangway, but that in no wise deterred them from clambering the sheer forty feet of the ship’s side. A rope was thrown up and grasped by willing hands among the emigrants already aboard. Then a stout square-bui1t woman would make the lower end of this fast about her waist and give the word to haul. There was great laughter and heaving among those on time deck end of the rope, as, with her feet against the side, leaping like a grasshopper, she shot up to the rai1 and was hauled over. The basket came next, laden with shawls, towels, lace, fruit and knick-knacks. The steerage people crowded around and bought what they wished. Then the woman and basket took another flight over a rail to the first-class quarters to continue her trading. By the time the emigrants were all aboard and the anchor was up the wares were sold out, and the woman and basket went down the rope into the boat as they came up. Every day in the year sees a liner in Queenstown harbor, sometimes more than one, so that the business done in this way must be excellent.

In the early days emigrants found their own bedding and food, but this custom has long since passed away. Government regulations provide that the menu shall be varied and ample. Three meals a day are served and a supper of hot porridge may be had at bed time if it is desired. Moreover in the steerage quarters there is always a cask of ship’s biscuit — hardtack — open and a lunch on these with dried herring may be had at any hour of the day. For the Jews, whose religion forbids much of the ordinary fare, especial provision is made, and no man need go hungry at any time. A bell calls to meals, but this is rarely needed. Sea voyaging is good for the appetite and a crowd besieges the dining-room doors long before it is rung.

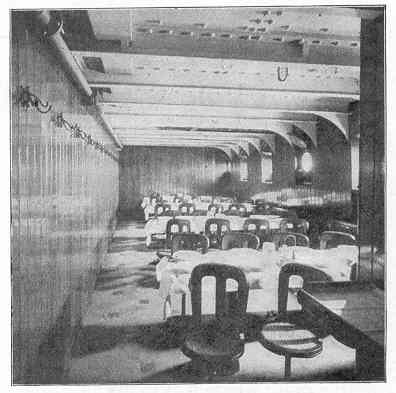

The dining-room to which I was assigned held a hundred or more, seated ten at a table in swinging chairs, much like those of the first-class saloon, though less sumptuous in polish and upholstering. The stewards tried to see that you had the same seat at each meal, but the task was a difficult one. Many of the emigrants were too stupid or too careless to heed this rule and you were apt to find your seat preempted by a seven-foot Scandinavian who was deaf to exhortation and who stolidly submitted to pushing or pulling without moving. If you appealed to the steward two could generally hoist him out, and he would move on, unresentful, to sit in the next vacant chair.

|

The tables had white cloths, and were set with breakable crockery, plates, mugs, four-tined forks, knives and spoons, with pepper and salt in castors, of the same quality you will find in the average restaurant ashore. Two stewards were assigned as waiters at each table and brought on and removed the food with celerity, good nature, and care to see that each man was served amply and as promptly as possible. There was little lingering at a meal, however, as a second sitting had to be provided for, and the motto “Step lively” seemed to prevail both with stewards and diners.

Supper came at six. It usually consisted of plenty of good bread and butter, sometimes fish, jam and marmalade and tea. For breakfast we had bread and butter, jam, Irish stew, or kippered herring and coffee. Our Sunday dinner the third day out consisted of soup, plenty of good roast beef and potatoes, peas, pudding and two oranges each. You were not limited to one helping nor did you have to order. The steward took it for granted that you wanted all that was coming to you and put the courses in front of you in quick succession. Most of the seventeen hundred took their oranges on deck and ate them there.

And right here let me say a word for the steerage steward. His wage is moderate, his tips few and small, and the mob of people he has to handle would drive a better and a wiser man to despair. Yet I have rarely seen him ill-natured or even really rough, though he often has to drive emigrants in a vociferous way in order to do anything with them. Many of these people take refuge in a seeming stupidity and ignorance that is really veiled laziness and obstinacy. You will think surely that your man knows no English till you find him in a place where it is to his advantage to use it. Then you are sometimes surprised to see him able to speak fluently. There were sixty steerage stewards on the “Cedric” who warned and cajoled, swept, scrubbed and disinfected continually, day and night. And the result was a surprising cleanliness in the face of what might seem heavy odds.

As I became better acquainted with my fellow voyagers I found that most of them were not stupid, ignorant, or unclean in their habits. The small contingent of a hundred or so English were especially notable for their superiority in education and refinement, averaging about as well as the people you will meet traveling first-class, or even second, for it has been shrewdly said that money travels first-class, brains second in the average of ocean steamship life. Very many of the Irish emigrants come well within this category too, though others from the poverty-stricken bogs of the west were ignorant of the most rudimentary elements of personal cleanliness and behavior. Yet even these certainly possessed youth and high spirits, good nature, warm affections and a concertina to every dozen or so. The deck spaces of the “Cedric” are so huge that even the 1,700 third-class passengers did not crowd them, and ample room was offered for dancing to the music of these concertinas, every one of which on a pleasant day was in pretty steady service. Young and old danced until tired.

|

For an hour or two in the forenoon, in the afternoon and again in the evening the bar is open to the third-class, and beer, light drinks and tobacco are sold to the emigrants, who patronize it freely. During the open hours there was always a crowd pushing before the little window and reaching for drinks over one another’s heads, but the bartender was judicious and discriminating, and no one was allowed to get too much.

During the evenings the dining-rooms became social halls in which reading, writing and games came into vogue. The best of the dining-rooms aft were devoted to the families and single women, and the best of the emigrants gathered there. One of them contained a piano and became the scene of several impromptu concerts, which, while managed without much ceremony, would vie in interest with those of the upper cabins. The young man, or the young woman who recites pathetic ballads with Delsartian gestures is not a patron of the first saloon alone. You find such elocutionists traveling third-class and equally eager to thrill their fellows, so that “Curfew Shall not Ring To-night,” “The Letter that Went to Papa,” “Hiawatha,” and “The Holy City” are not to be escaped by shipping third class.

The ship was so big and she moved with such majestic steadiness that there was very little seasickness, even at the start; and as the voyage progressed and the people were better acquainted, deck games became prevalent among the men, largely of the rough and primitive sort, that were carried out with vigor and unfailing good nature. Sometimes it was a sort of blind man’s buff or leap frog or puss in the corner; but all these gave way before the tug-of-war between nationalities. A group of English and Irish started this, their opponents being the Swedes and Norwegians. And just here the stolid Norwegian showed unexpected aptitude for team work. Twenty or thirty of these mountaineers, six feet tall, on one end of the rope, heaving in perfect unison, would haul the Englishmen along the deck again and again. Yet the English pluckily kept up the unequal contest. One suspects that the Norwegians had had training in just that work in their life among mountains and fjords. In the end Hans and Ole would get tired of pulling their opponents about and some of them would leave the rope. Thereupon the English, with a final effort and a great cheer, would rush things their way, conquering finally by sheer dogged pluck, as has been the way with Anglo-Saxons from time immemorial.

|

On the second or third day out came the ordeal of vaccination. Then indeed did the ship’s doctor earn his salary. The 1,700 emigrants passed in review before him with arms bared and each, unless the arm showed undisputed proof of previous vaccination, must be vaccinated in good earnest. The work is often divided into two days, the men being taken on the first, the women and children on the second. Among the latter there is oftentimes weeping and wailing — as indeed frequently among the men — not unaccompanied with the gnashing of teeth, though all must submit willy nilly. It is quick work for the individual and as a rule submitted to with smiling fortitude. Some ship’s doctors, wise in their generation, delay this duty till the voyage is several days old.

On a day during the voyage the tickets were taken up. We were brought together into a given portion of the deck and passed below in a line, one by one. If your ticket was simply for New York it was taken up. If you had booked through to some further destination you were given in exchange tickets for that place, by rail or boat. Then on a given day the purser had a lively session with the third class for the changing of money. Marks, francs, drachmas, lira, roubles and kroner, all in small sums, were exchanged at a good rate for Yankee dollars. The day was one full of vexations and hard labor for the purser, yet not unprofitable, for the sums exchanged in the aggregate are large and a little commission goes into his own pocket for his trouble.

The voyage drew to an end. The pilot came aboard and the thirty-ton anchor slid to the mud at quarantine. Here again we were crowded upon the deck to pass the quarantine doctors in a single line with bared heads. All these things must you do, whether an American citizen or not. But when the ship arrives at dock, you have but to give the authorities proof of your American citizenship and you pass free to the shores of your own country along with the first and second-class passengers. If you are not a citizen the further ceremonies and delays of Ellis Island, whither you are taken on a tender, await you. What happens to the emigrant there does not concern this article.

|

I have heard and read tales of poor food and insufficient water on emigrant ships, of desperate sanitary conditions. Such stories may have been true in the past. They certainly do not apply to the modern ships. In the third-class quarters on the “Cedric” there were numerous faucets with a chained dipper to each. Here at any hour of the day you could get all the good drinking water you wished. The lavatories were ample and as clean and well fitted as those of the average city hotel, supplied with all the appliances of modern plumbing and kept scrupulously neat by the vigilant and untiring stewards. There were washrooms with plenty of water and clean towels daily. You might, and most of the emigrants did, keep clean thereby with ease.

It is not the ship’s fault if you do not have reasonable comfort as a third-class passenger. Everything possible is done to help you out. Certainly a man in good health, who is alert and resourceful, may to-day cross the ocean in the steerage and have a comfortable time of it, finding more, perhaps, to interest and amuse him than he would if traveling first class. Among the 1,700 third class in the “Cedric” that trip there were at least one hundred who seemed amply able financially to travel in the other classes. That they preferred to go with the emigrants merely proves that as a result of competition in ocean travel the steerage has been steadily improved, and that its accommodations are to-day in many instances superior to many of those of first-class cabins of a score or more years ago.