| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2008 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

XV

WITNEY AND MINSTER LOVEL ALTHOUGH, as the crow flies, but ten miles distant from Oxford — that city which, "steeped in sentiment as she lies, spreading her gardens to the moonlight, and whispering from her towers the last enchantments of the Middle Age," attracts unnumbered thousands within her gates every year — few indeed are the visitors from the outside world who disturb the repose of Witney. Yet for historic interest and placid pastoral scenery few districts in the county can hope to compete with this little town and its surroundings. Excitement

must not be sought here, nor any "sights" save such as

yield their spell only to the reflective eye. Over church, and

marketplace, and the ancient houses which line the spacious main

street of the town, seems to brood the peace of a far-off age. Life

is not altogether idle here, for human hands are yet active plying an

industry of remote antiquity; but that pursuit of the practical is

powerless to disturb the all-pervading calm. Man and nature seem

attuned to the solemnity of the silent church spire uplifted to the

unresponsive heavens, or to the murmurless flowing of the river

Windrush as it wends its noiseless way to the Isis and the sea. Here, "but

careless Quiet lies

Wrapt in eternal silence far from enemies."

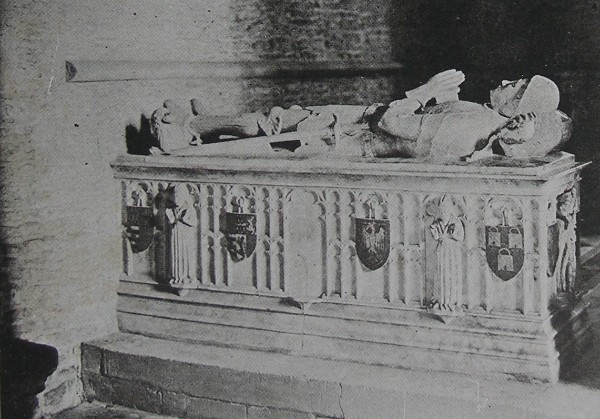

For untold centuries life has changed but little at Witney. "Could we for a moment raise the veil," writes a careful county historian, "we should probably find that the county life of 400 A. D. in Oxfordshire was not very dissimilar to that of to-day." The advent of the power of Rome and its departure, the raids of Jutes and Engles and Saxons, and even the coming of the Normans had only peaceful issues in this retired neighbourhood. Had Witney been a considerable city there would have been another story to tell; for the Saxons, hating city life and all that belonged to it, had then wrecked their vengeance on the place. But its rural peace could not fail to recommend the little settlement to those lovers of village life. That it found favour in their eyes seems proved by the Saxon name of the town, which enshrines as in a fossil the record that this was Witan-eye, or the "Parliament Isle." MINSTER LOVEL FROM THE MEADOWS An old proverb declares that Witney is famous for the four B's — Beauty, Bread, Beer and Blankets. Perhaps that accounts for its self-contained history. The community which possesses a liberal supply of those commodities can afford to be independent of the outside world. To affirm that to-day the town maintains its supremacy in all the four B's might be a hazardous undertaking, but there can be no danger in declaring that so far as blankets are concerned its proud position is unassailed. Notwithstanding the competition of modern times, and the notable improvements which have been made in manufacturing processes, Witney blankets are still famous throughout the world as the finest of their kind. Nor is that a surprising fact. Considering that the natives of this town have been engaged in the occupation for unnumbered centuries, that generation has handed down to generation ever ripening experience, it would have been strange indeed if the craft had not here attained its greatest perfection. Two explanations are offered for the location of the blanket-weaving industry at Witney. One of these has to be placed to the credit of the river Windrush, which flows so peacefully through the town. According to an ancient authority, the superiority of Witney blankets is due to the waters of the river being rich in nitrous, "peculiar abstersive qualities." Whether chemical analysis confirms that theory is not on record. In fact a curious enquirer asserts that if "you ask any of the Witney manufacturers if this be really the reason the manufacture has remained there so long, you will not be successful in getting a straightforward answer to a straightforward question — merely an amused look, with which you will have to be content." But why destroy all our pleasant illusions? If it could be proved that the Wind-rush is not responsible for Witney blankets doubts would begin to arise whether the Trent is really responsible for the virtues of Burton ale. Even, however, though the Windrush be robbed of its glory, there is another stubborn fact to be met. Without doubt Witney is situated in the heart of a great wool-growing district. It stands in close contact with the Cotswold country, which has always been famous for its luscious pasturage and its rare breed of sheep. WITNEY BLANKET HALL Whatever the original cause, the natives of Witney have been blanket-weavers for untold generations. The exact date of the founding of the industry has been lost beyond recovery, but there are countless proofs that by the middle of the seventeenth century it was in a flourishing condition. William J. Monk, in his contribution to the "Memorials of Old Oxfordshire," writes: "Henry III, when a boy staying at Witney Palace with Peter de Roches, had some of his wardrobe replenished here, as an entry in the Close Rolls shows, and it would be easy to prove that other sovereigns visited it upon many occasions, and it may be for the same purpose. Here came James II in the midst of his troubles, and perhaps the inhabitants endeavoured to solace him in his woes; at any rate, they do not appear to have been unmindful of the respect which was due to him as the sovereign of these realms, since they presented him with 'a pair of blankets with golden fringe.' In later days came George III with his little German spouse, and they, too, were given a pair of specially made blankets." But, though prosperous, the blanket-weavers of Witney were not without their troubles. During the reign of Charles I some court favourite appears to have obtained a Patent, otherwise a tax, on the Witney blankets, and pressed his advantage so closely as to have made necessary an appeal to the House of Lords for redress. Half a century after that extortion had been removed, the weavers found their craft endangered by interlopers and "frauds and abuses" introduced in "the deceitful working up of blankets." Those old weavers held a high opinion of their craft; it was, to their thinking, an "art and mystery," the latter word perhaps conveying their appreciation of the occult "abstersive" properties of the Windrush. Any way, they grew anxious to protect their industry, and, after the manner of early eighteenth century political economy, they arrived at the conclusion that a close corporation would serve their purpose best. Hence

the appeal of the Witney weavers to Queen Anne for Letters Patent

giving them the power of incorporation, an appeal which reached a

successful conclusion in 1710. This adroit move had an architectural

result which is still in evidence in the town. Needing a building in

which to exercise their powers, the incorporated weavers erected the

Blanket Hall, a structure which, though no longer devoted to its

original use, yet bears mute testimony to an early experiment in

protection. High up on the front of the building, beneath the clock,

the arms of the company are still in evidence, which include three

leopards' heads, each having a shuttle in its mouth. The motto of the

corporation was: "Weave truth with trust," a sentiment

which a local poet, penning an "Ode to Peace" in 1748,

devoted to the muse in the following lines: "Industry

to Temp'rance marry,

That we may WEAVE TRUTH WITH TRUST; Hence let none our fleeces carry, But be to their country just."

No sooner had the weavers of Witney received authority from the crown than they promptly proceeded to use it. One of the earliest entries in the records of the meetings held in the Blanket Hall tells how a member was fined five shillings for giving his daughter work at one of his looms while at the same time refusing employment to a journeyman who had demanded it; and a year or two later another member was mulct in ten pounds for presuming to take a second apprentice into his employment. One of these entries would seem to suggest that the Witney weavers were not of a martial disposition. In 1745, the date of the first Jacobite rising, the corporation was required by the government to supply thirty men for service against the rebels. A meeting was hurriedly called in the Blanket Hall to debate on the order, and careful consideration of the royal mandate revealed the fact that one guinea in "ready money" would be regarded as an acceptable substitute for each man. The Witney weavers sent thirty guineas! THE BUTTER CROSS AT WITNEY Another Witney survival of the past is the picturesque Butter Cross, standing in the marketplace. This structure owes its existence to William Blake, a native of the adjacent village of Coggs, who caused it to be erected in 1683. At that time, and for many generations, it was probably used as a kind of pro bono publico stall for the venders of butter on market-days, but now it seems to be the recognized loafing-place of the town. It seems to be more than likely that the Butter Cross was erected for utilitarian ends on a site which had previously played its part in the religious life of Witney. Prior to the Commonwealth, most of the towns of England had their market-cross, consisting generally of a statue of the Virgin and the infant Christ, and it is quite feasible that Witney was no exception to the rule. When this was swept away by the austere Puritans, what was more likely than that its place should be occupied by a structure which would offer no chance to offend their irritable religious susceptibilities? Less than three miles from Witney are two centres of interest which no visitor to the town should overlook. One of these is the derelict colony of Charterville, disfiguring the pleasant Oxfordshire landscape with another of those monuments to folly which socialistic experiments have scattered over the land. It had its origin in the Chartist movement of sixty years ago, and was one of the five estates purchased by Feargus O'Connor. This particular estate, comprising some three hundred acres, was split up into plots of two, three and four acres, on each of which a small three-roomed cottage was built. As soon as any subscriber to the general fund had paid in a total of five pounds, he was eligible to take part in the ballot, and if he drew a prize he entered at once on the possession of his cottage and land. And every care was taken to give him a fair start on his rural career. The land was ploughed ready for sowing, and a sum varying from twenty to thirty pounds placed in the hands of each settler. But the scheme was a dismal failure. At Charterville the dumpy little cottages, set down just so in the midst of their plots, may still be seen; and conspicuous among them is the large building which was to serve as school and general meeting-house for the colonists. The schoolhouse is a barn and tenement; the cottages have become the homes of agricultural labourers. Many of the first owners remained but a week or two; the charms of rural life quickly palled, and they returned to their towns with the balance of their capital plus the goodly sum realized for the scrip which gave them legal right to cottage and land. For such, no doubt, the scheme was not a failure, but in the mass it was overtaken with that fate which appears to be the inevitable lot of all idealistic communities. Only a few minutes' walk distant is a picturesque nook which quickly obliterates all memory of the ugliness of Charterville. At the bottom of a gentle valley, embowered among trees, set in the emerald of deep-bladed grass and reduplicated in the clear waters of a placid stream, nestle the priory farm, the church, and the ruined manor-house of Minster Lovel. Once more the peace of the ancient world asserts its soothing influence, and the spirit becomes receptive to the legends of old romance. Eight centuries have come and gone since the Lovel family reared its first roof tree in this enchanting dell. So long ago as 1200 a lady of that race, Maud by name, founded a priory close by, whence the hamlet became known as Minster Lovel. It was dissolved in 1415, and fifteen years later William, Lord Lovel, had built the stately manor-house which is now crumbling to decay within a stone's throw of his tomb. Many a noble family in England shared in the disaster which overtook the last of the Plantagenets on the field of Bosworth, conspicuous among them being that Francis, Viscount Lovel who was lord of this dismantled mansion. He, it will be remembered, figures among the dramatis personæ of Shakespeare's "Richard III," but if he had taken no more prominent share in the adventures of that monarch than the dramatist credits him with his fate would hardly have been so tragic and mysterious as it proved. Shakespeare, however, did not know what is known to-day. Evidently he was unaware that Francis Lovel was the youthful companion of Richard, that he bore the civil sword of Justice at his coronation, that he was created Lord Chamberlain, and that he is inscribed on royal records as the King's "dearest friend." He was among the few loyal and devoted knights who galloped with Richard in his final and fatal desperate charge at Bosworth, and for two years thereafter he approved his unshaken devotion by heading little bands of heroic insurgents against Henry VII. For his reward he was placed high in the list of noble persons attainted for their adherence to Richard, and that document records that he was "slain at Stoke." But was Francis Lovel slain at Stoke? It is the impossibility of answering that question which gives the ruins of Minster Lovel their most romantic association. That at the battle of Stoke, in 1487, Francis Lovel fought with as much valour as though Richard himself were present, is attested by Francis Bacon in his "History of King Henry VII." But he adds that eventually Lord Lovel fled, "and swam over the Trent on horseback, but could not recover the other side, by reason of the steepness of the bank, and so was drowned in the river." Yet legend, and more than legend, will have it that Francis Lovel regained his stately home by the side of the Windrush. Bacon himself knew of another report, which left him not drowned in the waters of the Trent, "but that he lived long after in a cave or vault." The fuller story tells that when he reached Minster Lovel once more he shut himself up in a vaulted chamber, confided his secret to but one faithful servant, to whom he entrusted the key of his hiding-place and the duty of bringing him food from time to time. Well was the secret kept, and faithfully the duty discharged, till there came a day when death suddenly overtook the devoted retainer. And day followed day, and night succeeded night, and no food any more reached the lord of Minster Lovel. Generations later, in 1708, the Duke of Rutland was at Minster Lovel when some structural alterations were being made in the manor house. In the course of their excavations, the workmen laid bare a large underground vault, in which they found the skeleton of a man, reclining as though seated at a table, with book, paper, and pens before him. MINSTER LOVEL  LORD LOVEL'S TOMB With such a memory freshly renewed, the visitor can hardly fail to enter the nearby church in heightened mood. And in that peaceful little building, an exquisite example of the Perpendicular style of architecture, he will find a tomb of unusual beauty. This is not the resting-place, as is sometimes stated, of Francis Lovel, but of his ancestor, William, Lord Lovel. There is no inscription on the monument and the hand of time has so effaced the coats of arms that their heraldic secrets are as hidden as the fate of Francis Lovel; but for delicate workmanship, and for rich suggestion of the age of chivalry this alabaster memorial is a priceless survival. Far distant, and voiceless here, are the clamours of the modern world; with his sword for ever at rest, and hands folded in eternal supplication, this knightly figure shall know no reawakening to those intrigues of the court and those conflicts of battle which have left their shadows on the tottering walls of Minster Lovel. |