XX

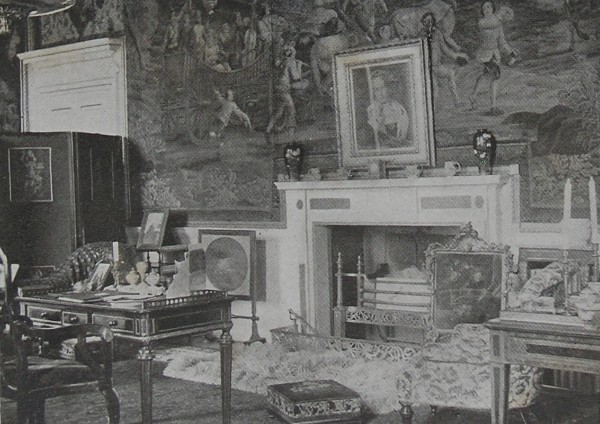

A HIGHLAND NOBLE'S HOME FIVE or six miles from the head of Loch Fyne a small bay indents the west side of the lake, and on a gently-sloping lawn in the centre of that bay stands Inverary Castle, the chief seat of the illustrious family of Argyll. It is a fitting home for the head of a great Highland clan. To the right rises the conical hill of Duniquaich, with its sombre watch-tower on the summit, recalling those lawless days the memory of which contributes not a little to the romance of the Scottish Highlands. On the left, nestling almost under the shadow of the castle, lies the royal town of Inverary, the latter-day reminder of a time when the followers of a great noble were safest within bow-shot of his fortress. The background is shut in by tree-clad hills, which sweep down to the right and left on either side of the river Aray. Bannockburn laid the foundations of the fortune of the Argyll family. Although the bards of this noble house claim for it an antiquity reaching back to the shadowy times of the fifth century, the earliest authentic charter connected with the family belongs to the year 1315. Among the adventurous Scots who sided with Robert the Bruce in his struggles for the Scottish crown was one Sir Neil Campbell, of Lochaw (the modern Loch Awe), and so lively a sense did the king entertain of the services thus rendered, culminating at Bannockburn, that he rewarded his follower with the hand of his own sister, the Lady Mary Bruce. It was to Sir Colin Campbell, eldest son of this union, that the charter mentioned above was granted, and it secured to the king's nephew the barony of Lochaw on condition that he provided, at his own charges and whenever required, a ship of forty oars for the royal service. It does not appear when the Argyll family took up their residence at Inverary; all that is certain is that it was long prior to 1474, for in that year King James III, "for the singular favour he bore to his trusty and well beloved cousin, Colin, Earl of Argyll," created the "Earl's village of Inverary" a free burgh or barony. Turner's etching of Inverary Castle is most remarkable for its intolerable deal of landscape to one half-penny worth of castle, and yet it is a characteristic transcript of the district, for no matter from what distant standpoint the upper reaches of Loch Fyne are viewed, the pointed turrets of the Duke of Argyll's home cannot fail to arrest the eye. But it is from the public grounds of the castle that the most picturesque views of the building can be obtained. Whether seen through glades of trees with the sunshine transforming its sombre stone into deceptive brightness, or blocking the end of one of the many avenues which stretch away into the park, or with a background of threatening thunder-clouds massed up Glen Aray, the castle asserts itself as the central point in these wide domains. If an uninterrupted view of the building is desired, it may be had either from the bridge over the Aray on the road to Dalmally, or from the private gardens of the castle. It is quadrangular in shape, with four round towers; comprises a sunk basement, two main floors, and an attic story; and is dominated in the centre by a square tower which rises some feet above the main building. When Dr. Johnson visited the castle in 1773, he told Boswell that the building was too low, and expressed a wish that it had been a story higher,— a criticism which has been met to a certain extent, for the dormer-window story is a later addition. It is to the third Duke of Argyll that the present structure is mainly due. Lord Archibald Campbell states that when this ancestor of his had planned a new abode, he, in 1745, ordered the old castle to be blown up, as no longer fit for habitation. A still earlier predecessor, according to a Highland legend, met a yet more singular fate. The lord of the castle in a far-off age, who was distinguished for his magnificent hospitality, when visited by some nobles from Ireland was specially anxious to entertain them in his superb field-equipage, which he was accustomed to use on a campaign. That he might have a reasonable excuse for this departure from usual hospitality, he caused his castle to be destroyed just before his guests arrived. The present building dates from 1744-61; but there was an interruption in the work for a considerable period during the unsettled times of 1745. The third Duke of Argyll is also credited with planning the grounds around the castle. THE ARMORY, INVERARY CASTLE Appropriate in its outward setting as the chief home of MacCailean Mor — the Gaelic name, meaning "Great Colin's son," by which the head of the Argyll clan is known in the Highlands — Inverary Castle also betrays by its interior that it is the abode of a Highland noble. The vestibule leads directly into the central tower. This handsome apartment, known as the armory, extends upward to the full height of the building and is flooded with light from gothic windows at the top. Mingling with innumerable family portraits and other works of art are arms and armour of infinite variety and absorbing historical interest. Here are old flint-lock muskets which dealt many a death wound at Culloden, claymores which have known the red stain of blood, battle-axes which have crashed through targe and helmet, and halberds which have survived from fierce war to grace the peaceful ceremonials of modern times. From either side of the armory a spacious staircase leads to the second floor, and on one of the landings hangs a full length portrait of Princess Louise, the present Duchess of Argyll, flanked by a charming cabinet which is surmounted by an exquisite harp. The house of Argyll, it is said, has ever been famed for its harpers. To the left of the main entrance is the apartment in which Dr. Johnson and Boswell were entertained, now used principally as a business and reception room. The three chief apartments of the castle extend the whole length of one side of the building, their windows commanding unrivalled views of mountain and glen. One corner is taken up with the private drawing-room of the duke and duchess. It is a dainty apartment, furnished in faultless taste, and hung with costly Flemish tapestry. This is not the only room so draped. More Flemish tapestry may be seen in the state bedroom, and this originally hung in the old castle. Again, the large dining-room is decorated with tapestry of the Flemish school, the colours being as vivid as when the cloth left the loom. Next to the private drawing-room, and opening off it, is the saloon, a spacious apartment richly decorated and containing many noble family portraits. The third room is the library; and here, at the small table on the left, it was the habit of the late duke to read prayers to his household. THE SALOON, INVERARY  THE DUCHESS' BOUDOIR, INVERARY Generously as the nobles of England have exerted themselves to do honour to and bestow hospitality upon such of America's sons and daughters who have visited the "Old Home," few of their number exceeded the late Duke of Argyll in the warmth of their friendship and the sincerity of their regard for their distinguished guests. The duke was a genuine lover of America and Americans. Although possessing a temperament which caused a fellow peer to describe him as having a "cross-bench mind," meaning that it was impossible to forecast which side he would take in a political crisis, he never assumed an attitude of hesitancy towards America and her children. "I think," he declared as the chief speaker at the memorable breakfast in London to Lloyd Garrison, "I think that we ought to feel, every one of us, that in going to America we are only going to a second home." And in perfect keeping with that sentiment was his confession to a correspondent: "It is the only disadvantage I know, attaching to warm and intimate friendships with cultivated Americans, that in a great majority of cases they are severed by distance before they can be lost by death. But I have enjoyed too many of these friendships not to be grateful for their memory." Throughout the Civil War the duke never faltered in supporting the side of the North. Hence the urgent appeals made that he would visit America. Henry Ward Beecher promised that he would "see that a Republican welcome can be more royal than any that is ever given to royalty;" and Whittier wrote: "Hast thou never thought of making a visit to the U. S. A.? Our people would welcome thee as their friend in the great struggle for Union and liberty, and in our literary and philosophical circles thou wouldst find appreciative and admiring friends." From

the year when he succeeded to the title the Duke of Argyll was ever

on the alert to offer the hospitality of Inverary Castle to

Americans, among the most notable of those received here as honoured

guests being Prescott, Harriet Beecher Stowe and Lowell. Himself a

man of letters of varied attainments, it can be easily imagined how

keenly the author of "The Reign of Law" would enjoy having

Lowell for his guest; and that Lowell did not fail of experiencing

equal pleasure must be obvious from the conclusion of the graceful

lines in which he recorded his "Planting a Tree at Inverary:" Who

does his duty is a question

Too complex to be solved by me, But he, I venture the suggestion, Does part of his that plants a tree. For after he is dead and buried, And epitaphed, and well forgot, Nay, even his shade by Charon ferried To — let us not inquire to what, His deed, its author long outliving, By Nature's mother-care increased, Shall stand, his verdant almoner, giving A kindly dole to man and beast. The wayfarer, at noon reposing, Shall bless its shadow ou the grass, Or sheep beneath it huddle, dozing Until the thundergust o'erpass. The owl, belated in his plundering, Shall here await the friendly night, Blinking whene'er he wakes, and wondering What fool it was invented light. Hither the busy birds shall flutter, With the light timber for their nests, And, pausing from their labor, utter The morning sunshine in their breasts. What though his memory shall have vanished, Since the good deed he did survives? It is not wholly to be banished Thus to be part of many lives. Grow, then, my foster-child, and strengthen, Bough over bough, a murmurous pile, And, as your stately stem shall lengthen, So may the statelier of Argyll!

Tree-planting seems to have been the tax usually imposed on every notable visitor to Inverary. Harriet Beecher Stowe paid her tribute to the castle grounds, and so did Queen Victoria, and many other less exalted guests. A love for trees seems to have been a common trait of the Argyll family. More than a century and a quarter ago, when Boswell piloted Dr. Johnson through these well-wooded grounds, he, still smarting from the aspersions his companion had cast on the treeless character of Scotland, took a "particular pride" in pointing out the lusty timber of the demesne. Thanks, perhaps, to that unwearied industry in note-taking to which James Boswell owes his fame, the visitor to Inverary Castle will probably find his imagination more greatly filled with the figures of Dr. Johnson and his biographer than with those of royal and other guests of the house. It was on a Sunday afternoon in the autumn of 1773 that Boswell called at the castle to ascertain whether its ducal owner would like to extend his hospitality to the great lexicographer, whom he had left at the inn in the village. The lord of Inverary at this time was John, the fifth Duke of Argyll, who was satirized by the fribbles of his day because, instead of wasting his guineas on the gambler's-table, he devoted his wealth and his thought to the improvement of his estate and the welfare of his tenants. And the lady who bore the honoured name of the Duchess of Argyll at this period was none other than the beautiful Elizabeth Gunning. Unhappily, no matter how gladly the duchess agreed with her husband in his desire to honour Dr. Johnson, she had adequate reasons for not entertaining the same feelings towards Boswell. He had figured aggressively in a law-suit in which the duchess had been keenly interested, and that on the side adverse to her. Still, the traditions of Highland hospitality had to be observed, and the duchess, while assenting to an invitation to dinner for the following day being extended to Dr. Johnson and his companion, evidently anticipated that an opportunity would present itself for effectually snubbing Boswell. At the dinner-table the irrepressible Boswell made several attempts to placate the antagonism of his hostess. He offered to help her from a dish beside him, and, when that service was coldly declined, lifted his glass to her with the toast, "My Lady Duchess, I have the honour to drink your Grace's good health!" Afterwards, in the drawing-room, says a recent biographer of Elizabeth Gunning, the beautiful duchess, who still continued to ignore Mr. Boswell, called Dr. Johnson to drink his tea by her side, when, perhaps with the intuition of genius, there came to him a revelation which never failed to capture his great warm heart, and he perceived that this radiant lady was a good mother. For he knew that she had fought a brave fight for her little son; he could see that her wounds were still fresh and bleeding. She had asked him why he made his journey so late in the year. "Why, madame," he replied, "you know Mr. Boswell must attend the Court of Session, and it does not rise till the twelfth of August." In a moment the fair brow was clouded, and her voice grew stern. "I know nothing of Mr. Boswell," she answered sharply. Imperturbable,

even after cooler reflection, Boswell himself gave to the world the

history of his visit to Inverary Castle, and the episode was seized

upon by the pen of Peter Pindar for the following lampoon: As

at Argyll's grand house my hat I took,

To seek my alehouse, thus began the Duke: 'Pray, Mister Boswell, won't you have some tea?' To this I made my bow, and did agree — Then to the drawing-room we both retreated, Where Lady Betty Hamilton was seated Close by the Duchess, who, in deep discourse, Took no more notice of me than a horse. Next day, myself, and Dr. Johnson took Our hats to go and wait upon the Duke. Next to himself the Duke did Johnson place; But I, thank God, sat Second to his Grace. The place was due most surely to my merits And faith, I was in very pretty spirits; I plainly saw (my penetration such is) I was not yet in favour with the Duchess. Thought I, I am not disconcerted yet; Before we part, I'll give her Grace a sweat — Then looks of intrepidity I put on, And ask'd her, if she'd have a plate of mutton. This was a glorious deed, must be confess'd! I knew I was the Duke's and not her guest. Knowing — as I'm a man of tip-top breeding, That great folks drink no healths whilst they are feeding, I took my glass, and looking at her Grace, I stared her like a devil in her face; And in respectful terms, as was my duty, Said I, 'My Lady Duchess, I salute ye:' Most audible indeed was my salute, For which some folks will say I was a brute; But, faith, it dashed her, as I knew it would; But then I knew that I was flesh and blood.

FREW'S BRIDGE, INVERARY  INVERARY CASTLE A ramble through the grounds of Inverary Castle reveals them to be both spacious and well-kept, and they are nearly always generously open to the public. One of the principal roads leads towards Dalmally, and it passes over a bridge — Frew's Bridge — to which a legend with a dash of humour is attached. At his first attempt the builder of this bridge failed, and his structure collapsed — whereupon he ran away; but the duke of that time fetched him back and made him do his work over again — with happier results, as the present soundness of the structure bears witness. Close by, and within a few yards of the Aray, is the silver fir planted by Queen Victoria in 1875. There are many magnificent avenues in the park, notably one of limes which leads to Eas-a-chosain Glen — that glen of which Archibald, the ninth earl, declared that if heaven were half as beautiful he would be satisfied. |

Web and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio

1999-2008

(Return to Web Text-ures)