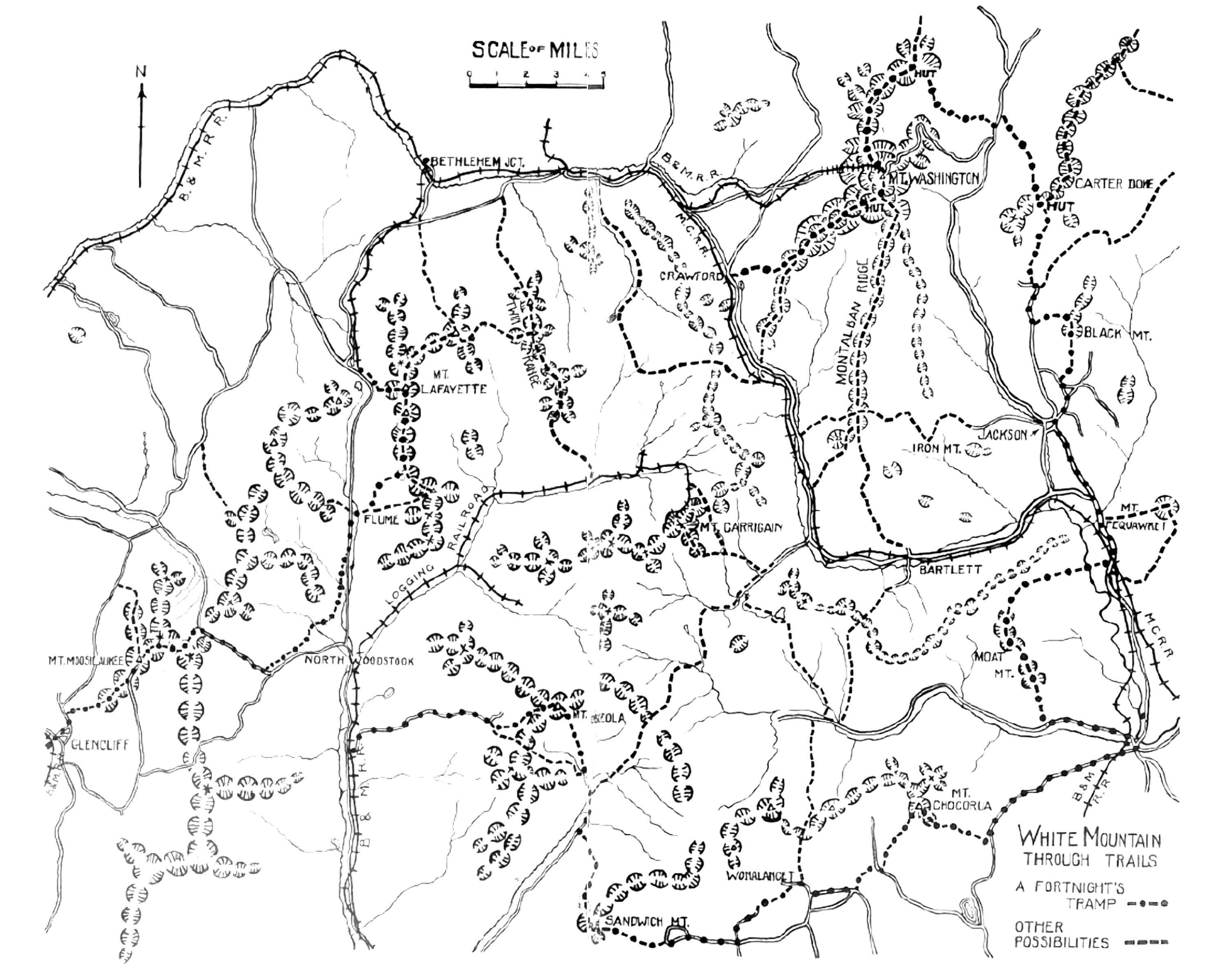

| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2019 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Vacation Tramps in New England Highlands Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

|

III

A SUMMER SAUNTERING FOR the professional hobo New Hampshire is

a most

inhospitable region. For the hiker it is a paradise. There was a time

when

hotel clerks in fashionable mountain resorts looked with haughty

disdain upon

the man whose only baggage was a pack-bag. For a considerable period,

too, even

the farmer-folk looked askance at the man with dusty boots, for the

tramp

terror had been stamped deeply upon the New Hampshire countryside by

repeated

professional hobo outrages. It required drastic special legislation to

rid the

State of this pestilential vagrant, and although that legal prohibition

still

stands in force, it is clear that the people are now able to

discriminate

between tramps and trampers, until farmers and hotel-men alike as

readily open

their doors to-day to the latter, as they vigorously slam them against

the

former. The advent of the automobile drove the

bicycle off

the roads, but to the gentle art of tramping it is destined to be a

stimulation. No car can ever encroach upon the mountain trails, which

will always

remain sacred to the hiker, while out on the open road, the auto is his

friend,

helping him cover monotonous stretches of hot highway, and providing,

through

the increasing patronage of its devotees, new moderate-priced hotels

that cater

to the transient. As for trails, they increase in number

yearly. Old

Abel Crawford and his son, those pioneer hotel-men of the mountains,

recognized

that trails were as essential as frying-pans to their business, for

people went

to the mountains to go into the mountains in those days. There were no

such

counter-attractions as golf and tennis tournaments, or motor trips on

valley

roads. But he who went into the mountains a hundred years ago (and it

is

considerably more than a century since the first hotel was built where

now

stands Fabyans)1 had to pick his own way and rough it. In

recent

years the mountaineering clubs have opened mile after mile of trail,

even to

the remotest ravines and summits, and latterly the hotels, noticing

that there

are still those who go to the mountains for their own sake, have

followed the

example of the Crawford family and have built pretty paths for the

ramblers

and good trails for the walkers who may chance to be guests beneath

their

roofs. There are times when two is a company and

three a

crowd, but that does not necessarily apply to a jaunt of this nature.

A third

man has his good points, and for the sake of even numbers and general

good-fellowship a fourth also may be considered. But Thoreau's precept

as to

companions may well be kept in mind. The charting of the course in advance is

important,

and one of the most enjoyable features of the trip. Let the controlling

factors

be that there shall be a minimum amount of railroading and motoring

involved,

that the days' marches shall not be fatiguingly long, that a good bed

shall be

available every night, and that, without recourse to high-priced

caravansaries,

also that the cream of the scenery be included in measures of standard

size.

This requires careful study and consideration of the best maps and

guide-books

of the region to be covered, and the timetables of the railroads (for

the

White Mountains this means the running schedules of the White Mountain

and

Portland Divisions of the Boston & Maine, of the White Mountain

Division of

the Maine Central, and of the Grand Trunk), and the summer resort lists

issued

by those same roads as well, these latter to furnish hints as to

stopping-places along the way. Four of us, who knew that we could travel

together on

the Thoreau principle for two weeks, thus planned out what we

considered the de

luxe tramp of the White Mountains. Our time limit was the traditional

two

weeks' vacation. Our daily mileage was to be governed by what we could

do in

comfort. There was to be no attempt at big stunts or record times. The

impetuosity of youth had long since ceased to dwell with any of the

four. We

knew that blistered feet had no place in the good time we planned. One

mile an

hour uphill was to be our gait, with three times that at a steady swing

on level

going. Due allowance was made for occasional hold-ups on rainy days,

and rights

were reserved to change our course at will should the inclination

prompt it.

It all worked out to a charm. In two weeks, in the midst of an

abnormally heavy

rainfall, but one day was lost from that cause. Only twice were we

caught and

thoroughly soaked (even waterproofs are not invulnerable at all times),

and on

both of these occasions this was due chiefly to our own carelessness.

And only

once did the weather force a radical change in the day's programme. The itinerary of the trip, in the main

devoid of

flourishes as to its scenic charms, may be sketched in briefest form

for the

benefit of him who would follow on. Glencliff, at the height of land between

the

Pemigewasset and Connecticut waters, was our jumping-off place. Three

trains a

day from Boston stop there, and quarters for the night are available in

the

little village by inquiring of the station-master. Arrivals by the two

earlier

trains will have no cause to tarry here except on account of weather,

and the

Dartmouth (College) Outing Club's trail to Moosilaukee summit is easily

found

by inquiry at the station. It is a beautiful trail, well watered,

steady, and

easy of grade, and Moosilaukee is well worth a climb, for the view it

commands

is extensive. For those who ascend in the afternoon the little summit

hotel

offers shelter and substantial fare, but if the ascent is made in the

morning,

four hours and a half being amply sufficient for the slowest walker to

cover

the five miles, the descent into Kinsman Notch can be made during any

three

hours before sunset. We felt that the full day that we devoted to the

mountain

was anything but wasted, the morning spent in a leisurely ascent, the

afternoon

in roaming about the moor-like summit tableland, followed by a

refreshingly

restful night in that clear upper air.  The trail down the eastern slopes of Moosilaukee Within a scant half-mile of where the

trail down the

eastern slopes of Moosilaukee emerges upon the State highway in Kinsman

Notch,

we found the tidy log cabin of the Society for the Protection of New

Hampshire

Forests, where the custodian made us welcome with food of a filling

sort, and

bunks fragrant with newly pulled balsam tips. Kinsman Notch, until the

building of the State road in 1915, was an almost unknown region. The

Beaver

Meadows and the underground passages of Lost River, now protected

within the

three-hundred-acre reservation of the Forestry Society, are among the

notable

attractions of the mountains. It is singular that this gorge, now

deservedly

famous as the third great natural wonder of the Franconia section of

the

mountains, should have remained undiscovered until 1895, within seven

miles of

a long-established summer resort. The profile of the Old Man of the

Mountain

on the Cannon Mountain cliffs, overlooking the Franconia Notch, has

been known

far and wide for many years. So, too, the Flume, at the southern end of

the

same great notch, has been one of the notable spectacles of the

mountains ever

since mountain touring began. And yet the Lost River lay hidden in the

forest

until a local guide stumbled upon it by chance only twenty-odd years

ago. In

the estimation of one of its earliest explorers, the late Frank O.

Carpenter,

of Boston, it "far surpasses the Flume in its surprises, its massive

rock

architecture," and is "unique in its dark, gloomy caverns."

Though but three or four hundred feet wide, this cleft in the mountain

extends

from a third to half a mile, the stream corkscrewing its way through

the dark

passages from forty to seventy-five feet below the crest of the canyon

walls.

One of the first to make the passage of these Stygian caves found that

three

hours of continuous exertion had been required for the trip. To-day,

thanks to

the bridges and ladders placed by the Forestry Society, the

difficulties and

dangers have vanished, and a single hour suffices for the easy passage

through.

Just what caused this tumbled mass of

rock, which

now, as a spectacle, attracts thousands of sight-seers every year, has

somewhat

perplexed those geologists who have seen it. In the opinion of Robert

W.

Sayles, of the Department of Geology at Harvard University, who has

studied the

caverns, this river became lost perhaps twenty-five thousand years

ago, when,

toward the close of the glacial period, an earthquake shook the cliffs

above

and tumbled down the great blocks that now fill the gorge, burying the

stream

from sight. The great pot-holes in the stream-bed, which are among the

curiosities of the present day, he has pronounced to be the largest

known

anywhere in this country, and he thinks that they must have been

caused,

perhaps just prior to the earthquake, by a torrent of water that poured

through

the notch from the melting glacier that filled the great valley to the

westward. Of this he feels certain, although admitting that the

earthquake

theory requires further study for complete substantiation. The next attraction along the route is the

walk

across the ridge of the Franconia Range, but it is a half-day's tramp

thither

through the woods from Kinsman Notch to the hotel at the Flume. The

first three

miles is on the highway toward North Woodstock, which brings the

tramper to the

site of a burned logging mill. Here the bed of the old lumber railroad

leads

sharply to the left, and winds around through the woods six miles to

its

junction with the Franconia Notch highway, two miles below the Flume,

all of

which may be covered in a long forenoon. A lazier way would be to

continue on

the highway from the old mill for four miles to North Woodstock

village, with

a glimpse of the Agassiz Basins on the way, and catch the motor stage

up the

Franconia Notch on the morning or afternoon run. A pleasant afternoon

at Flume

need not drag, for the trail behind the hotel leads in an hour to the

top of

little Pemigewasset Mountain, a glorious viewpoint for the notch

ranges, and

back toward Moosilaukee. Or if upgrade walking is not attractive,

there is

the stroll to the Pool, and up the road to the great pot-hole known as

the

Basin.  One of the great pot-holes in Lost River’s Gorge It being a piping-hot morning when we

turned out at

Bethlehem Junction and cast our eyes toward Mount Washington, we

readily

decided to spare ourselves the unnecessary toil of clambering up the

Mount

Pleasant path, and bought our railroad tickets through to the Summit

Station

instead of to the Base. Doubtless many would prefer to railroad around

to

Crawfords, and ascend by the historic Bridle-Path to the Appalachian

Mountain

Club's hut at the Lakes of the Clouds, a glorious stroll of six miles,

more

than half of it above the timber with the world unrolled beneath.

Mountaineer

beds and fare are at the service of all comers at the hut, or real beds

may be

found at the hotel on the summit of Mount Washington, an hour's climb

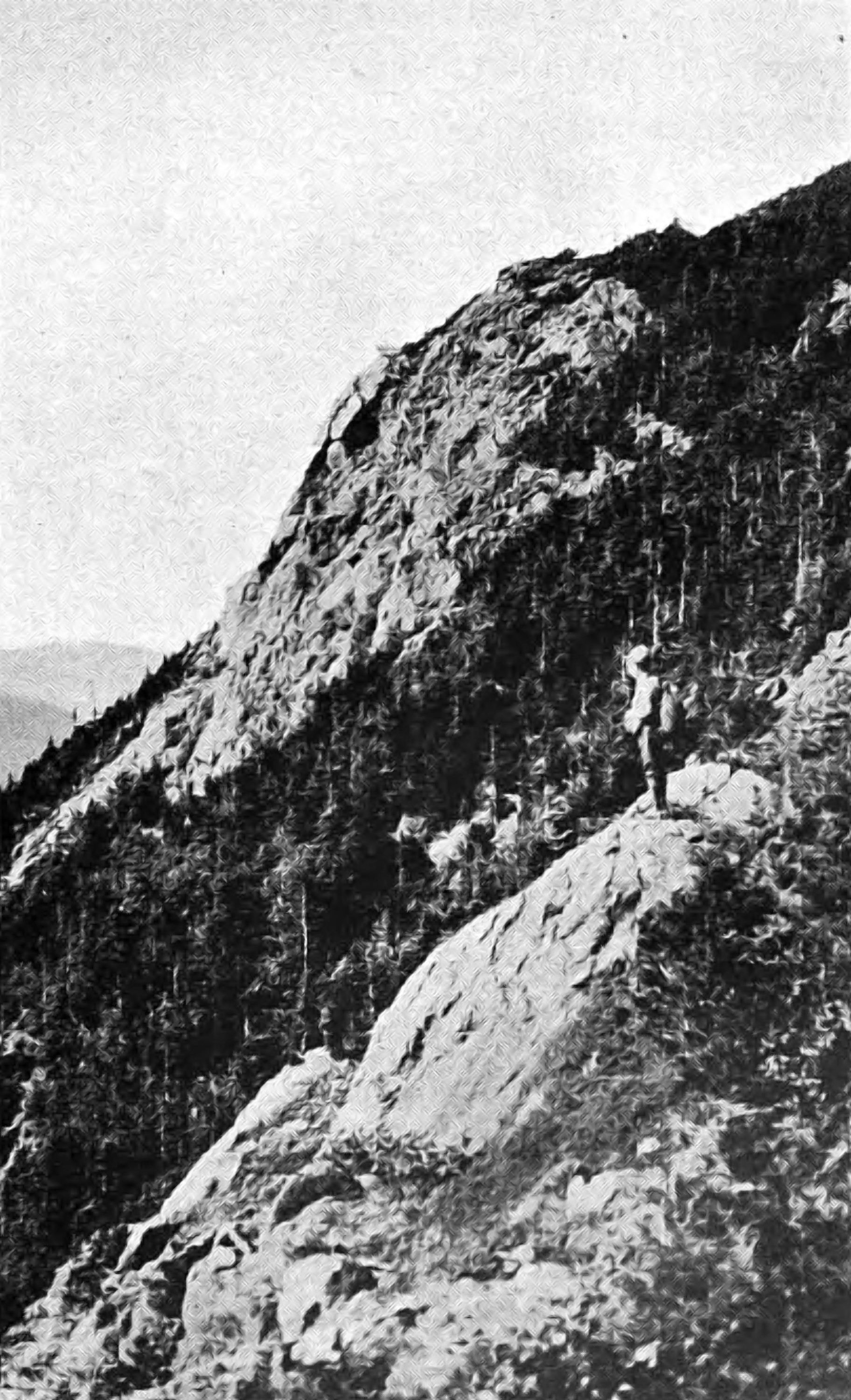

beyond. A more alpine approach to the Great Range

would be to

continue on the train to Willey House Station, and clamber up the

cliffs of

Mount Webster by one of the most interesting trails in all the

mountain

region. But it is long and it is steep, and from Webster's summit to

the Lakes

of the Clouds hut it is eight stony miles. Only the stoutest of legs

should

attempt it, and in nothing short of the finest of weather.  The cliffs of Mount Webster To cross the Franconia or the Presidential

Ranges in

a simple summer cloud may not be prudent for the inexperienced, as the

trails

are dim amid the rocks, and the cairns are readily missed. To attempt

to force

their passage in a cold and freezing rain, a condition that is

sometimes

experienced at those altitudes even in summer, is positively perilous,

and

lives have already been sacrificed to such foolhardiness. From the Madison huts to the Glen the map

will show a

choice of mutes, or if it is voted that this should be the climax the

railroad

is easily reached in less than four miles of downgrade on the opposite

hand. A

prime favorite Glenward is through the virgin forest of Madison Ravine

by

Parapet Brook and the Gulf. With us a leisurely week had already been

consumed, and the descent was made for a Sunday amid the semi-urban

joys of

Gorham, whither our spare clothes had preceded us by parcel post. To complete the circuit of the mountains

through the

east and south the obvious route from Gorham leads over the crest of

the

Carter-Moriah Range. From the outskirts of Gorham village the trail

leads

across the Huggermugger Bridge and up the slope of Mount Surprise, with

its

inspiring view of Mount Madison and Mount Washington, and continues on

over the

summit of Mount Moriah and down into the saddle of Imp Mountain, an

easy day's

ramble, but one that involves the necessity of camping at this point in

the

Appalachian Club's shelter. Another similar day, still following the

ridge

trail south over the Carters to the Dome, brings one at night into the

remote

fastnesses of the Carter Notch with its hospitable hut. Till comes that

happy

day, and come it will, when a hut is opened midway the Carter Range,

the easier

road to the notch along Nineteen-Mile Brook will doubtless be the

choice of

most. Crawford Notch, Franconia Notch, and

Pinkham Notch

are all well-known White Mountain localities, but, except to a

comparatively

small number, Carter Notch is scarcely more than a name. To the

tramping

fraternity it is known as a wild gorge between the Carter-Moriah and

Wildcat

Ranges, but as neither railroad nor wagon-road passes that way, no

others have

seen the beauties of its precipitous walls, or felt the charm of its

sparkling

twin tarns. To those whose strength of wind and limb have carried them

into this

wild spot it has a fascination that draws them again and again, not

only in

summer, but in the dead of winter as well. Now that this notch has

come into

possession of Uncle Sam as a part of the White Mountain National

Forest, it is

destined to be better known, for as time goes on the Government will

open up

such places with better trails, trails adapted to saddle animals as

well as to

pedestrians. For one descending Mount Madison through the Gulf, it is

an easy

afternoon's stroll from the Glen into the notch, where a day may be

most

enjoyably spent in exploring its caverns, in whipping the lakelets to

lure

their speckled trout, or in climbing to the summit of the overhanging

Dome for

its wide and much-repaying view. From Carter Notch a pleasant valley trail

leads to

the south five miles to the upper end of the Jackson valley, there

connecting

with a path to the summit of Black Mountain with its observatory,

which

commands one of the best views of the Great Range. If the trail along

the ridge

of Black is followed south from the tower toward Jackson village, a

most

interesting day can be completed within a total of some ten far from

difficult

miles. A night in one of the numerous hotels in

Jackson and

again the future road must be mapped out. It is a safe assumption that

the

first step thence will be toward Mount Pequawket's summit, most readily

reached

from the Jackson side by the Pitman Trail, some four miles down the

Thorn

Mountain road in Lower Bartlett. Descending from Pequawket to Intervale

for the

night the next most attractive possibility is to cross the interval and

the

Saco River to Diana's Baths for the ascent of North Moat Mountain,

spending

the day in the ramble along the ridge toward the south. If a telephone

message

has been sent ahead in the morning before setting out, for a helpful

automobile

to meet the rovers as they emerge on the Albany Interval road in the

late afternoon,

the day will end with a comfortable night at the hotel at the foot of

the Weetamoo

Trail to Mount Chocorua, the starting-point for yet another day. Chocorua sentinels the eastern end of the

southernmost rampart of the mountains, the Sandwich Range. No White

Mountain

trip could be complete for us that omitted the climb up Chocorua's

rocky crest,

with a night at the little house that snuggled for twenty-five years

beneath

the cone. Wrecked by the great gale of September, 1915, it was restored

in part

the following year only to be again swept away in that winter's storms.

Homely

it was in the Yankee sense, but in the hearty greetings of its veteran

landlord, David Knowles, and in the unpretending but generous quality

of its

entertainment, there was true homeliness. The pleasant memories of that

little

house among the rocks, that remain with thousands who have been its

guests,

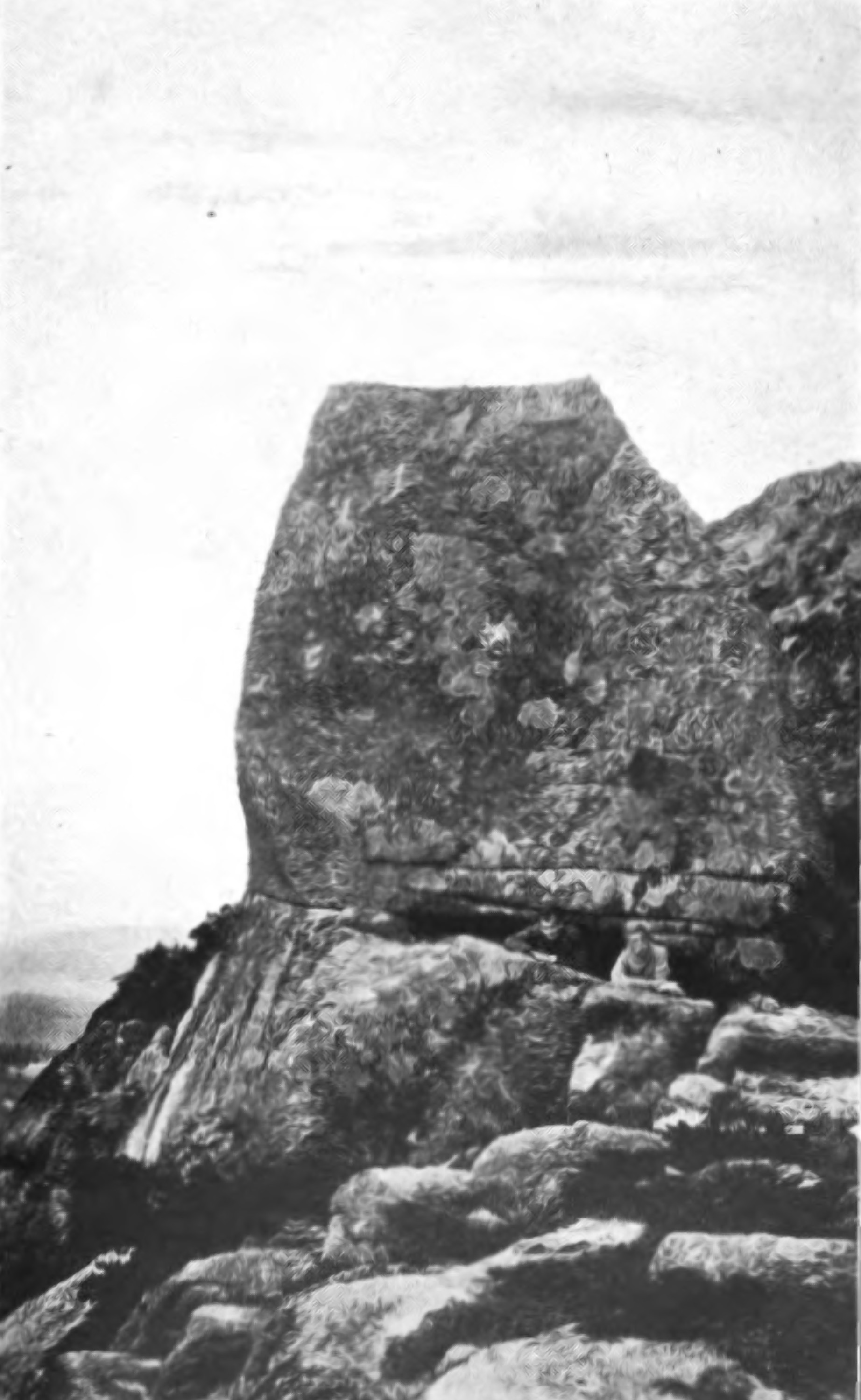

afford a firm foundation for its successor. Now that the only refuge that the

mountain affords

is the chilly cavern beneath the great Cow Rock, where Frank Bolles

once passed

a lonely vigil with the stars, few will know the glories of a night on

that

windy watch-tower, but will seek their shelter in the valley to the

south. A

long summer's day will be ample to cross the mountain, descending

through the

fine old forest along the Brook Trail, or by the Bee-Line route, with

its

recurring backward views of the cone above, to Paugus Mill and

Wonalancet

village. With two more full days Sandwich Mountain will be crossed, by

way of

Whiteface Interval and Jose's Bridge, into Waterville,- and Mount

Osceola

ascended for the final stretch down its western side to the railroad at

Woodstock, almost at the foot of Moosilaukee once more.  Chocorua’s Great Cow Rock

* The mileage and elapsed time are

cumulative for

each day, distance and time being figured from point last named in

previous

line. The times here given are sufficient for leisurely walking. MAPS: White Mountain National Forest, two

miles to

the inch, published by the U.S. Forest Service. Mailed on application

to Forest

Supervisor, Gorham, N.H. Eleven sectional trail maps of the White

Mountains,

drawn by Louis F. Cutter, and published by the Appalachian Mountain

Club,

Boston, Mass. 1

Eleazer Rosebrook, grandfather of Ethan Allen Crawford, opened his

house to

travelers in 1803. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||