V

ALONG THE SKY-LINE TRAIL

IN the midst of the Green Mountains a new

trail had

been born. Such news is ever an irresistible lure to one with the

tramping

habit. With him there is always "something lost behind the ranges."

The oldest trail, indeed, is a promising field of exploration till he

has

experienced it. No matter how many may have preceded him, the mysteries

of the

unknown are yet before him — lost and waiting for him —

he simply has to go. But here was a

brand-new trail, its last blaze but lately made, and one leading

through a

forest region in large part unscarred by axe or fire.

It seemed a far cry, though, to the Green

Mountains

for a man with only a week-end to spare — to

steal might be a more truthful expression —

until, in the light of the

night-train

schedules, even that two-hundred-miles off region appeared as but

around the

corner.

The sleeper train is the ever-ready

accomplice of

the man in such a frame of mind. His desk is closed at night, and,

presto !

breakfast is ready at "the jumping-off-place. "

Then, too, it is less trying to the nerves

of the

sensitive man, who perhaps does not feel that he looks his prettiest in

his

trail garb, when he can crawl, unobserved, into his berth, and can as

easily

escape the public gaze in the early morning. Truth to tell, though, the

tribe

of the tramper has so increased that the woodsiest apparel scarce

attracts a

glance, except one of envy, to-day. We "fell for it," and,

breakfasting in Burlington, caught an. early train south that

connected with

the branch line for Bristol, whither the telephone's summons had

insured the

presence of a helpful "flivver "to cover the eight miles of valley to

the journey's real beginning.

With more time at our disposal the choice

would

undoubtedly have been to spend a night in Lincoln village, about

halfway between

Bristol railroad station and the trail, or at the Davis farm only a

mile and a half

from the "jumping-off place," where trampers mostly stay.

There still remained a full hour of

morning when

packs were hoisted at the foot of the break-neck road up the

Lincoln-Warren

Pass, where, at the height of land, at a point proclaimed by a

Geological

Survey bench-mark to be 2424 feet above the sea, the Green Mountain

Club's Long

Trail arrows bade us turn our faces northward up Mount Abraham.

Before us lay a trail on which we might

follow, if so

we wished, for three whole days without contact with civilization, yet

with

livable cabins and lean-tos handily located along the way, affording

shelter

against everything except the insinuating and boot-consuming porcupine.

Should

foul weather or other mischance so will it, escape to the western

valley farms

was easy by three side trails, with one farm so conveniently situated

within a

mile of the- main course as to afford most comfortable quarters for the

night.

With three or four days more to spare, the

trail

leads on, to and across Mount Mansfield, and over the Sterling Range, a

mere

reversal of that midsummer trip "Over Vermont's Highest Spots." For

us it was to be a three days' joy ride, with shoulders burdened with

nothing

but the barest necessaries. As dear old "Nessmuk" once put it:

"We do not go to the green woods to rough it; we go to smooth it."

Nothing takes the joy out of life along the trail more completely than

a

weighty pack slung upon unaccustomed shoulders. If a wool-wadding

sleeping-bag,

with its paraffined balloon-silk cover, weighing six pounds, will keep

you

reasonably warm, and that without turning in all standing, why tote

more? If

the night is chilly, you presumably have a sweater and dry socks to

don. If

still you think that you ought to shiver, it is a safe bet that it is

because

of the vagrant zephyrs stealing in around your neck, and that this can

be

easily cured by chinking the crevices there with a flannel shirt.

We started with an axe, but I left it in

the train.

It was the other fellow's, anyway. I am afraid he missed it, although I

didn't.

For grub-stakes our list was meager in variety, but bountiful as to

quantity.

John Muir was wont to take to the mountains for weeks at a time with

nothing

but a bag of dry bread, sugar, and tea. Bread, too, was our reliance,

but

garnished liberally with two of Vermont's choicest products, good

butter and

soft maple sugar. All mountains have their genii, 't is said, but be

they gods

or demons that flourish at those altitudes, no Vermonter need fear

their anger

while lasts the secret of the ambrosial Green Mountain sandwich. Bacon

there

was also in our stores, likewise cocoa and sugar cubes, but the only

kitchen

outfit consisted of our belt cups and pocket-knives. Pork broils

appetizingly

on a forked stick, and a slice of bread held conveniently at hand the

while

conserves the drippings.

It was such a gypsy jaunt as makes old

boys young.

Never did skies smile more graciously upon a wayfarer. "Daylong the

diamond weather, the high, unaltered blue," kept with us on our favored

way. Credit it to the good weather if you will, the fact remains that,

although

the partners were here for the first time met (a rash experiment

according to

all woods lore), no human frailty intervened to mar one single hour.

Nobody

spoiled the cooking; nobody snored (so far as known); not even the

owner of the

axe complained at its loss, a fact in itself that is fraught with

significance

to every woodsman. A pet axe may not be carelessly treated by

strangers or by

friends with impunity, nor alluded to other than in terms of

respectful

consideration.

For my own part it was not altogether

because of the

newness of this particular bit of trail that the trip especially

appealed. From

time to time tidings had come from this section of the Green

Mountains, the

Lincoln and the Bread Loaf groups, telling of the charm of their

unbroken

forest mantle, and of the public-spirited idealism of the man who was

their

owner. The late Colonel Joseph Batten was a son of Vermont who saw

values in

his native mountains and their forests other than those that could be

calculated in thousands of feet board measure. More than fifty years

ago his

vision showed him a day when fine timber would be scarce. Even then he

began

buying mountain lots along the main range, until people thought him

daft and in

need of restraint. In later years, as timber rose in value, his

one-time

critics began to think him shrewd. Little they suspected, though, that

these

purchases, that at the time of his death, 1915, had extended for

approximately

thirty miles along the mountains, and aggregated thirty thousand acres

or

more, were not of a speculative sort.

He bought what he wanted when it offered,

but he

never sold. Now and again he parted with a little of the timber, when

it did

not interfere with his plans, but never to be butchered. Until his will

was

read it is doubtful if any one other than his lawyer knew what were his

plans

for these great forest holdings. After his death it developed that

those plans

were entirely in the interest of his heirs, and that, as a bachelor, he

had

elected that all who dwell or tarry within Vermont should be his heirs

in this.

As one of his executors has said, it was scenery, not timber, that he

had been

so persistently acquiring in all those years. For what reason? Let the

language of his will explain.

"Being impressed with the evils attending

the

extensive destruction of the original forests of our country, and being

mindful

of the benefits that will accrue to, and the pleasures that will be

enjoyed by,

the citizens of the State of Vermont, and the visitors within her

borders, from

the preservation of a considerable tract of mountain forest in its

virgin and

primeval state," he bequeathed this property to the officers of

Middlebury College, his alma mater, as trustees for the college and the

public.

A few years before his death all his lands on Couching Lion Mountain

were given

to the State of Vermont for public enjoyment and profit as a State

Forest.

Taken as a whole, there can be no doubt

but that the

Batten forest is the largest and handsomest remaining tract of primeval

timber

in this section of the country, and future generations will surely

praise the

name of him whose foresight and unselfishness saved for Vermont this

splendid

relic of that feature which gave to the State its name. Thus, in one

way or

another, through such benefactions as that of Colonel Bartell, through

the

establishment of public forests by the State, and through the

trail-building

activities of the Green Mountain Club, Vermont is acting on the

suggestion

once made by Lord Bryce in an address at Burlington. He there urged

that effort

should be made "to spare the woods whenever they are an element of

beauty, . . . to keep open the mountains, and allow no one to debar

pedestrians from climbing to their tops and wandering along their

slopes."

As an earnest of their desire to follow

that counsel

the people of Vermont formed their Green Mountain Club, to plan and

build three

hundred miles or more of footway throughout the length of their verdant

hills.

Year by year the trails lengthen out and improve in quality, and this

bit is

in truth a tramper's joy. Not only does it find every high spot where

broad

views abound, and that without incurring unnecessary steepness for mere

climbing's sake, but it hunts out every intervening charming dell and

glade and

ravine, every picturesque cliff, every refreshing spring, that could

possibly

be brought within the line of march without undue departure from the

course.

Except for a mile or two at the northern end, a bit that probably will

eventually be relocated to follow along the face of the southeastern

cliffs of

Couching Lion, there is not a monotonous inch in the whole

twenty-seven miles

from the Lincoln-Warren Pass to the Duxbury valley.

Trail signs of the Green

Mountain Club

In its construction also

the trail is as near

perfection as a mountain tramper has any right to expect. Not that it

is a

graded path, that horror of the pedestrian. Its excellence lies in the

wide

swamping of the brush and encroaching limbs, full six feet in the

clear, in the

painstaking grubbing-out of toe-tripping roots, and in the liberality

of the

directing signs and blazes. For one who enjoys the mild excitement of

uncertainty that goes with picking a way along a dimly spotted old

woods trail,

the frequent blazes on this route, with their three coats of white

paint, until

they literally blaze even in the night, might seem an affront to his

woodcraft.

If the beauty of the trail does not compensate for this, and serve to

prompt

the veteran's tolerance for that feature, he can find plenty of scope

for his

Indian instincts elsewhere. This trail was designed to open that

mountain

picture-gallery to every one, old and young, and especially to the

tenderfoot,

to conduct him through its mazes with certainty and safety. For any

one who

has ever followed the trail of the Bennington Section of the Green

Mountain

Club south from Mount Equinox toward the Massachusetts boundary by the

light of

its coral-red disc markers, the impulse is strong to think of this one

as the

white pearl trail.

For this model in mountain trails the

Green Mountain

Club, and the tramping fraternity generally, are indebted to the

idealism and

unremitting enthusiasm of the President of the Club's New York Section,

Professor Will S. Monroe, of Montclair, New Jersey.

In the course of his wanderings in many

lands he had

seen mountains galore, and had traveled the length of long miles of

trail. In

the Green Mountains he perceived great possibilities, provided that the

original inspiration for a sky-line route could be realized.

It was James P. Taylor, of Burlington,

Vermont, who

first proposed making the great mountain range of the State available

as a

recreation field for walkers throughout its length, a thought that at

once

appealed to the fancy of many of his fellow citizens, and that led to

the

organization of the Green Mountain Club in 1910. The plan likewise met

with the

approval of the State Forest Service, because of its economic

importance in the

scheme of fire patrol and protection, and, in cooperation with the

Club, the

cutting of the way was almost immediately undertaken by the forest

officers.

Unfortunately, however, the necessities of the forest patrol did not

fully

harmonize with the ideals of the tramper. A route across the ridges was

too

meandering and laborious to meet the foresters' needs, and the trail

that they ran

on easy grades along the slopes was far too tame and unspectacular for

those

whose quest was scenery.

It was in the midst of this disappointing

discovery

in 1916 that Professor Monroe offered his services for the building of

this

trail south from the southern base of Couching Lion by a route that

should be

the next thing to an aerial line. His labors began that very summer at

Montclair Glen, and season after season, with unabated zeal, his

vacations

were devoted to this work. It was a toilsome task and beset with many

bitter

discouragements. Camping in the mountains for weeks at a time, with

all that

that involves in the way of packing in supplies and the daily cooking

and camp

chores, in addition to the actual work of construction through weather

foul and

fair, and often under the torment of ravenous swarms of flies, calls

for a

degree of courage and persistency of an uncommon sort.

Professor Monroe's reward must be in the

knowledge

that by the autumn of 1918, after the equivalent of five months of

arduous work

distributed through the three years, he and his assistants, the latter

mostly

inexperienced volunteers, had to their credit almost forty-two miles

of as

perfect trail as could be built for the purpose. In recognition of

this

service the Green Mountain Club has officially designated his route as

the

Monroe Sky-Line Trail. It was in the exploration of the northern half

of that

stretch of trail that we spent these three October days.

Some years ago Colonel Battell cut a

buckboard road

up the west slope of Mount Abraham to an elevation within five hundred

feet of

the summit, and there built a commodious cabin of logs. That was in the

summer

of 1899. A trail ran thence three quarters of a mile to the top, and

three and

a half miles farther along the ridge to Mount Ellen, the highest point

of the

Lincoln group, with a spur trail down the western side from that

summit for

half a mile, where another lodge was built in 1903 at the edge of the

big

timber. Although these cabins have been sadly abused by unappreciative

humans

and by hungry porcupines, they are still reasonably sound and tight.

Elsewhere

along the trail, comfortable lean-tos have more lately been built, some

by the

Club, others through the generosity of Miss Emily Proctor, a member of

a distinguished

Vermont family. One of these camps is located in Birch Glen, a charming

ravine

a trifle more than seven miles north of Mount Ellen, and another close

under

the outstretched granite paws of the Couching Lion in Montclair Glen.

The Long Trail reaches Mount Abraham

cabin, not by

the Batten road, though that, too, is still usable by pedestrians, but

by a

route of its own over a southerly spur, an easy two hours' stroll.

Another

half-hour from the cabin puts one on the open summit at 4060 feet above

the

sea.

In the neighboring valley folks refer to

this summit

as "Potato Hill," and this notwithstanding that it was the citizens

of the town of Lincoln, at its western foot, who, back in '60, gave it

the name

of "Abraham "in recognition of the great emancipator, for whom the

town went solid in that memorable year. Mount Ellen, the highest point

of the

group, one hundred feet above Abraham's dome, was named by Colonel

Batten

himself. Subsequently, when the Coast and Geodetic Survey had

determined the

fact of Mount Ellen's greater stature, the Colonel's ideas of the human

fitness

of things is said to have rebelled at having a woman bigger than the

heroic

Lincoln, and, for his purposes, at least, he transposed the names of

Abraham

and Ellen. Until the work of the Geological Survey produces a completed

map of

the region, all names are unofficial, and those that have been accepted

or

applied by the Green Mountain Club will be as authoritative as any. As

to the

name "Potato Hill," that will soon be merely local history, inasmuch

as "Abraham" seems to have the call.

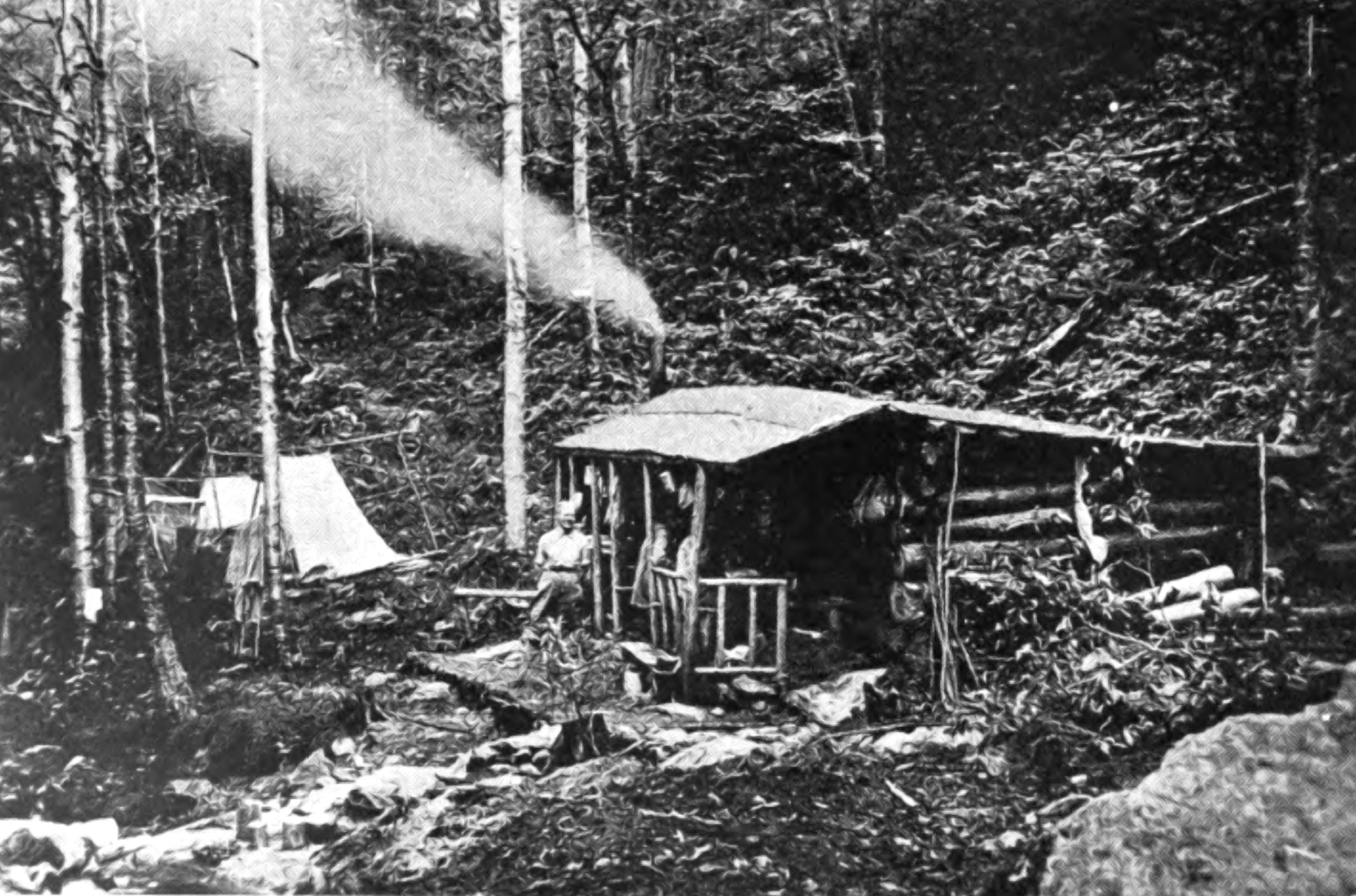

A camp on the Long Trail

Looking north from Mount Abraham's summit,

Mount

Ellen looms up across a deep and heavily forested bay, with a bit of

Stark

Mountain behind, the lesser intervening high points of the connecting

ridge, over

all of which the Long Trail runs, being Little Abraham, 3860 feet;

Lincoln

Peak, 3980 feet; Mount Boyce, 3880 feet; Batten Peak, 4060 feet; and

then Mount

Ellen, 4160 feet. Southerly the eye follows across the group dominated

by Bread

Loaf Mountain to Mount Carmel and Killington Peak, the latter nearly

forty

miles air-line away. East and west the range of vision reaches, on the

one

hand, to the White Mountains, and on the other into the Great Punch

Bowl vale,

wherein lie the farms of Lincoln, and through the nick in its western

wall to

the gleaming expanse of Lake Champlain and the close ranks of the

Adirondacks

with Mount Marcy and Whiteface bulking high above the rest. Close at

hand on

the eastern side one looks down into the valley of the Mad River, its

cultivated lands nipping into the wooded slopes on either side, a

peacefully

pastoral bit sharply contrasting with the rugged surrounding heights.

Nothing but the realization that four good

mountain

miles lay ahead to camp at Mount Ellen lodge could serve to hurry one

from that

outlook. But the view follows one along the trail; the frequent vistas

from the

ridge, now east, now west, with impressive plunging glimpses into deep

valleys, and the broader outlooks from some of the minor summits, fully

compensate for the regrets with which Abraham is left behind. Mount

Ellen

itself, being wooded at the top, commands no wide horizon, but that

defect

will one day be easily remedied by the construction of a timber tower

that

will clear the tree-tops.

Forewarned that no handy spring had yet

been located

near Mount Ellen lodge, canteens were filled at the copious and

constant

spring just north of Mount Abraham, where, about 1878 or 1880, R. D.

Cutts, of

the Coast and Geodetic Survey, had his camp. This spring needs to be

remembered

by all who pass that way, as it is the last drinking-place in a three

hours'

walk. As one of the avenues of retreat from the ridge to the

settlements lies

through the ravine below the Mount Ellen lodge (via a rough, abandoned

logging

road), this cabin will doubtless serve a valuable purpose in that

connection,

despite the want of a reliable water-supply nearer than half a mile

downhill.

For those who pack their shelter with

them, no finer

tenting-ground could be desired than that beside the spring at Glen

Ellen, the

saddle between the Lincoln and Stark Mountains, less than two miles

north of

Mount Ellen's summit. From the Lincoln-Warren Pass to this point,

eight and a

half miles, would be a comfortable day's tramp even with full camp

outfit,

allowing ample time for enjoying all the outlooks by the way. From this

camp-site in the glen is yet another route to the western valley, a

trail leading

down through the forest for half a mile to the junction with a good

wood road

which passes through the Hallock farm, not far from South Starksboro,

where

night quarters may be had.

The Stark Mountains, though not so high as

the

Lincoln, ranging up to 3675 feet, are no less beautiful in their dress

of magnificent

old forest, and the outlooks are frequent and interesting. From the

southern

end of the main summit the trail emerges upon a shoulder, the Champlain

Outlook, commanding an unobstructed prospect of fully one hundred and

fifty

degrees, from Whiteface in the Adirondacks on the west, to Couching

Lion, the

Chin of Mount Mansfield, and Jay Peak on the Canada border at the

north, and

to Mount Washington in the east.

Another hour, or a little more, of winding

among the

trees and moss-draped ledges, steadily dropping down a northern spur

the while,

and the top of Stark Wall is reached, the longest and steepest pitch of

the

entire trail. On the whole, the grades, which are far from difficult

anywhere,

are easiest when this walk is taken from the south, as in our case.

There is no

denying that Stark Wall is steep, and to one toting a goodly pack up

that hill

on a warm summer day it would as certainly seem long. Going north, one

rattles

down the pitches at a rapid pace, and comes to rest in a narrow

east-and-west

pass through which, once on a time, a highway ran. The old road

location may be

followed westward into Starksboro to-day.

Baby Stark and Molly Stark summits, each

about

twenty-eight hundred feet in elevation, have yet to be crossed before

Birch

Glen camp is reached at the edge of the settlement, the usual

stopping-place

for the night. During those last few miles the first traces of the

lumberman

seen since the beginning are encountered, but the cuttings are old,

and are

crossed only for short intervals by the trail. For those who, like

ourselves,

are not in full camping panoply, but another mile to the valley's edge

brings

one to Beane farm, where wanderers on the trail are always welcomed,

even by

the dogs.

As the trail runs it is fourteen and a

half miles

from the pass just south of Mount Abraham to the Beane place, and

exactly a

like distance if the old Battell road is followed up the first summit.

Over

this distance two youngsters once established an unpremeditated

record, in the

accomplishment of which they must have experienced not a few surprises

closely

akin to thrills. It is doubtful, though, if they would care to repeat

it even

as a lark, but it will serve to indicate the clearness of the trail

when it is

known that these boys tramped all through a moonless night, and without

a

lantern or torch of any kind. Their plan had been to gather in a stock

of food

at the last house, but luck was against them here, for the family

larder happened

to be too low to help them with so much as a crust. Banking on a rumor

that the

Mount Abraham cabin had lately been vacated by the trail-building crew,

who

were supposed to have left some supplies behind them, the boys,

banishing

prudence, took a sporting chance.

Dusk was settling when the cabin was

reached, but the

last flickering gleams of daylight served to show that old Mother

Hubbard never

was more certainly up against a bare pantry. There was plenty of meat

about,

but it was on the claw, so to speak, in the form of live porcupines.

Men lost

in the woods and starving have saved their lives more than once before

now by

eating raw "porky," but our heroes were not starving, thank you. A

hurried account of stock produced one banana, the remains of a dim and

distant

lunch, plus one broken match. Should they go back? Not for them. They

had come

from Massachusetts to go over that trail. With the aid of the match

they

examined and memorized their map, a mere sketch, and started. All night

they

traveled by the beacon light of white-painted blazes, and at

breakfast-time

pulled in to the Beane farm, famished and tired, conditions that Mrs.

Beane,

with youngsters of her own, knew how to cope with. Even if they did not

see

much of the trail, or anything of the landscape, they had had a grand

adventure

and voted it "some trip."

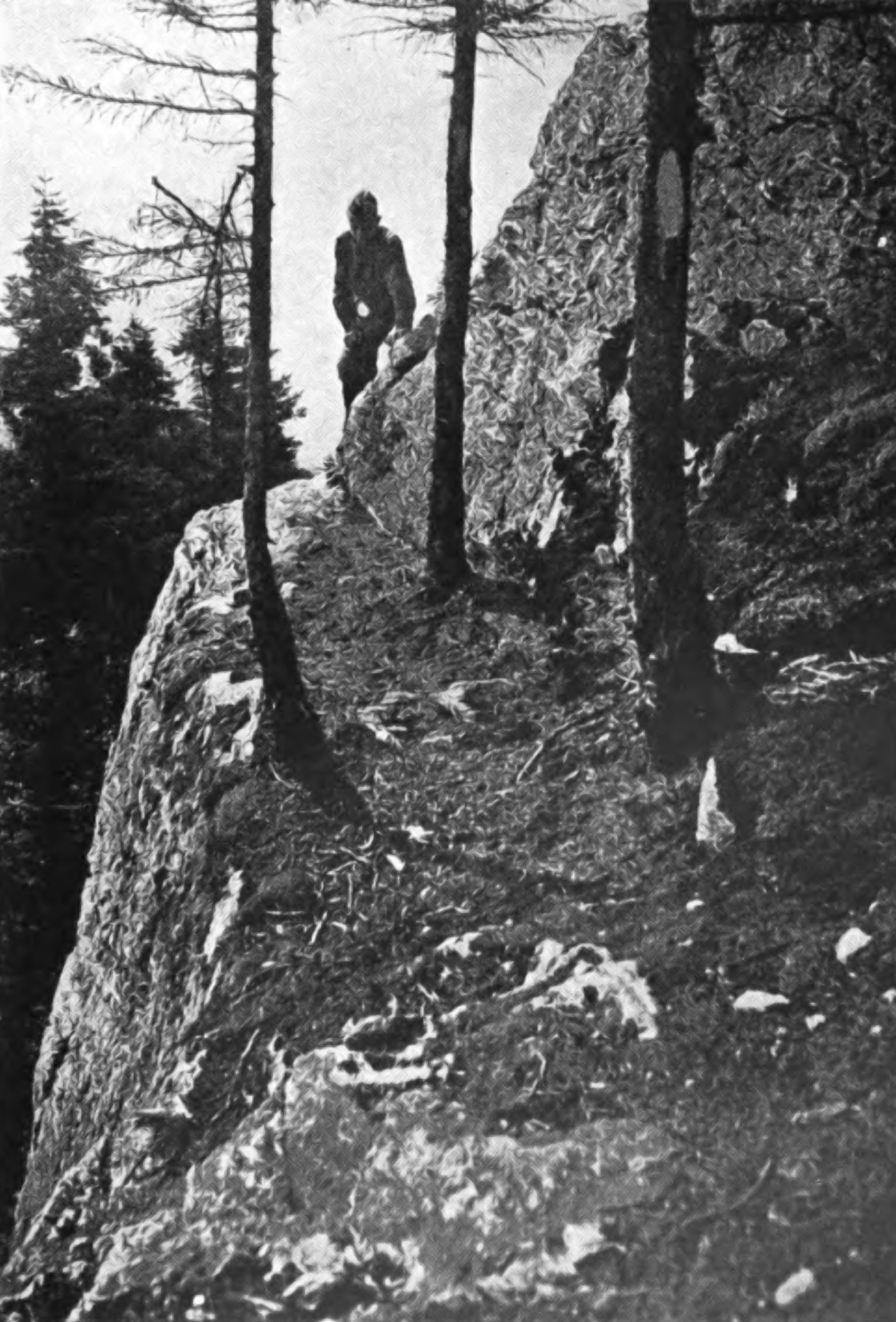

The ascent of the cone of

Burnt Rock Mountain

From Beane's to Burnt Rock Mountain, on

the trail

toward Couching Lion, it is a little less than five and a half miles of

easy

going through the woods. The ups and downs are only trifling, just

sufficient

to cross a few side ravines, though the rise is steady all the while.

Toward

the end of the first hour the Fayston-Huntington Pass is entered

through which

the official road map of the State shows a secondary highway as

running. The sojourner

on the trail will hunt here in vain for any sign of civilization beyond

the

benchmark of the Government survey (2217 feet), for that road was

abandoned to

the wild things more than sixty years ago, after the railroads came to

offer

easier outlets for the settlers in the Mad River valley to the east.

After skirting two intermediate wooded

summits along

the upper edge of a cut-over slope, across which the view to the New

Hampshire

mountains is unobstructed, the bare ledges of the cone of Burnt Rock

Mountain

come in sight, the trail ascending to its summit by a series of natural

stairways, galleries, and terraces. Three hours from the farm will

suffice to

put the tramper on this 3100-foot viewpoint. Just ahead Mount Ethan

Allen rises

with just the topmost rocks of Couching Lion appearing around the

spruce-covered shoulder. In another two hours and a half the series of

summits

of old Ethan's namesake will have been circled and passed, the Lion's

head will

loom up just beyond, his massive paws spread toward you, and Montclair

Glen be

reached, with its cabin latch-string hanging outward to every follower

of the

trail.

For those who find an added zest in the

experiences

of camping along the way, these cabins that the Club has built and

equipped are

an especial joy. They are likewise a boon to any who, through stress of

weather

or other mischance, may be in need of temporary shelter. It should be

an

unwritten law of the trail that in departing the guests should leave

behind no

trace of their occupancy in the shape of unextinguished fires, unwashed

utensils, or litter of any kind, and that a reasonable supply of dry

wood

should be provided in a sheltered place to cheer the next party,

which, for

aught one can tell, may arrive fatigued, after dark, or in the rain. A

good

woodsman needs no law to compel attention to such details. He knows

instinctively the etiquette of the forest road, and observes it

unfailingly.

Neglect in such matters marks the delinquent as a greenhorn and a boor.

Montclair Glen camp-site is charming

despite the fact

that it lies on the edge of an old burn. A terrific fire, fed by the

fresh

slashings of a lumbering job, swept the eastern and southern slopes of

Couching Lion during the summer of 1903, and its devastating effects

are even

now apparent in the stark gray crags, and in the gaunt and ghostly

forest of

dead spruce, now bleached by weathering. Where soil enough remained to

furnish

lodgment for seeds, the inevitable cherry and birch jungle has sprung

up, Nature's

machinery for the rehabilitation of the forest. The State Forest

Service has

been endeavoring to hasten the process by the planting of thousands of

spruce

and cedar seedlings, and with great promise of success, so that one day

the

glen will be as bowery again as are the opposite virgin slopes of Ethan

Allen

Mountain. The camp is perched upon a little knoll, beside which flows a

lively

brook of purest Vermont vintage, and looks up at the black-capped Ethan

on the

one side and upon the steep, bare granite of Couching Lion on the

other, while

to the west, between the two mountains, is framed a wide vista that

reaches to

the Adirondacks.

From the camp to the summit of Couching

Lion, or to

Callahan's farm at its Duxbury base, it is just two and three quarters

miles,

two miles of the way to the summit being across the burn. In following

the Long

Trail en mute for Mount Mansfield, a fork in the logging road, a mile

or so

from the camp, leads to the left and into the Callahan Trail to the

top, where

throughout the summer the Waterbury men maintain their modest hut in

charge of

a keeper.

For us the furlough was up, and, having

telephoned

from Beane's in the morning to have a motor sent from Waterbury to meet

us at

the base, we slipped down the mountain and made connections with the

sleeper

train for home.

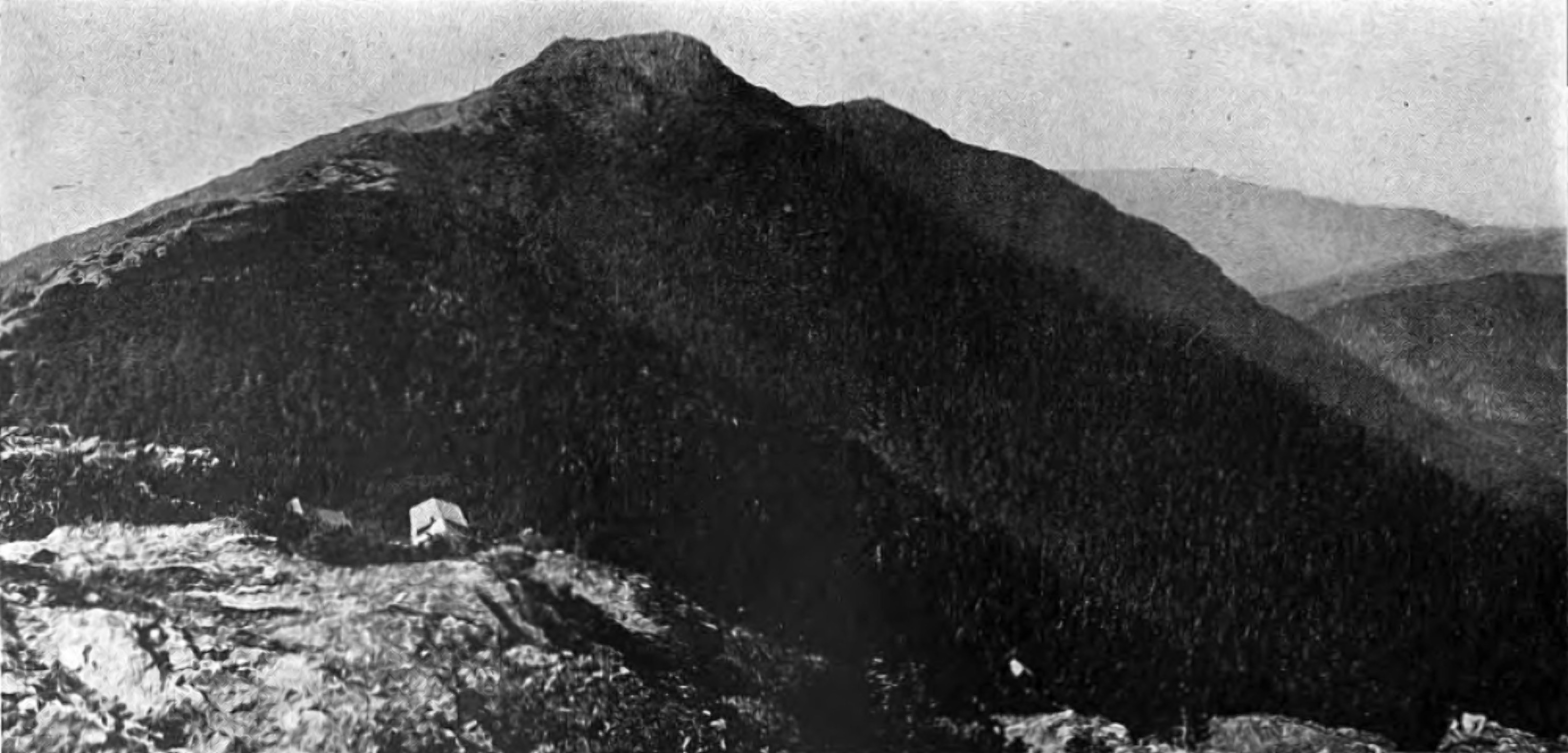

The Cone of Crouching Lion

over the forested spurs of

Ethan Allen Mountain

THREE DAYS IN THE OLD FOREST

First Day

MILES

HRS. MIN.

Bristol Station (Rutland R.R.)

by auto to Lincoln Pass

8.60

0 00

Lincoln Pass to Mount Abraham

To Lincoln Mountain summit

3.75

3 30

To Mount Ellen summit (cabin

54 mile more)

6.25

5 00

To Glen Ellen camp-site (side

trail west to South Starksboro

5 miles)

8.00 7 30

Second Day

Glen Ellen to Champlain Out

look

1.50

0

45

To Appalachian Pass (side trail

west to Starksboro road 3

miles)

4.00

2

15

To Birch Glen camp .

5.50

4

30

To Beane farm

6.50

5

00

Third Day

Beane farm to Burnt Rock

Mountain

5.40

3

00

To Mount Ethan Allen

7.50

5

00

To Montclair Glen camp

8.80

5

30

To Couching Lion summit (or to

Callahan's farm in 15% hours) 11.55

8

30

* The mileage and elapsed times are

cumulative for

each day, distance and time being figured from point last named in

previous

line. The times here given are sufficient for leisurely walking. The

second

day's walk may be done easily in five hours, but the scenery is worth

prolonging it to ten.

MAP: Monroe Sky-Line Trail, surveyed by

Herbert

Wheaton Congdon, and published by Green Mountain Club, Burlington, Vt.

AN ADDITION FOR GOOD MEASURE

The southerly half of Professor Monroe's

trail lies

over Bread Loaf Mountain and its satellite heights, and is twenty miles

in

length, from the Lincoln-Warren Pass to Middlebury Gap, through another

great

area of the Battell forest. With ten days to devote to a semi-camping

trip the

route might begin at Middlebury Gap and, taking the Long Trail there,

continue

over the Sky-Line to Couching Lion, Mount Mansfield, and out to Johnson

on the

north.

From the railroad at Middlebury an

automobile stage

runs thrice daily via Ripton Gorge to Bread Loaf Post-Office, somewhat

less

than three miles from the beginning of the trail in the depths of the

Gap, and

quarters for the night may be found at Noble's farm, or at the inn a

mile or

more beyond at the end of the stage line.

Three approaches to the ridge are

available from

this base, one from a point not far from Noble's farm and which

intersects the

Club trail close to the summit of Bread Loaf Mountain, one from near

the inn,

or the main trail which is farther east in the Gap. All these are shown

on the

Rochester topographic sheet of the United States Geological Survey,

edition of

1917.

Few would care to attempt the passage of

the entire

chain of peaks in the Bread Loaf group in a single day, for it is

nearly

twenty-two miles from the Gap to the Davis farm at the westerly end of

the

Lincoln-Warren Pass, and with many ups and downs. For that reason the

Club has

located one of its lodges beside a brook in an attractive glen just

north of

Bread Loaf summit, where all the comforts of a forest home, save food

and

blankets, await the wayfarer. The second night may be spent at the

Davis farm,

or in camp at the Battell lodge close under the summit of Mount

Abraham; the

third at Birch Glen lodge or at the Beane farm, within another mile;

the fourth

at Montclair Glen lodge, or at the huts on the summit of Couching

Lion three

miles beyond the Glen; the fifth in Bolton village; the sixth at Lake

Mansfield

Trout Club; the seventh on Mount Mansfield; the eighth at Barnes' Camp

in

Smuggler's Notch, or at the lodge on Morse Mountain; the ninth in

Johnson at

the northern end of the trail.

The length of the daily stages of such a

programme

would be as follows:

*MILES

Middlebury Gap to Emily Proctor

lodge

(Bread Loaf Mountain)

8.75

Thence to Lincoln-Warren Pass.

10.50

(To Davis', 12 miles; to

Battell lodge, 12.50 miles.)

Thence to Birch Glen.

13.50

“ “

Montclair Glen.

7.80

“ “

Couching Lion summit

2.75

“ “

Bolton village

4.50

“ “

Lake Mansfield

11.25

“ “

Mount Mansfield

6.25

“ “

Barnes' camp.

2.33

“ “

Morse Mountain camp

(estimated)

7.00

“ “

Johnson (estimated)

9.00

Total for eight or nine days

83.63

* One mile an hour is considered an

average leisurely

traveling time in such country for one with a moderate pack.

|