| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2019 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Vacation Tramps in New England Highlands Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

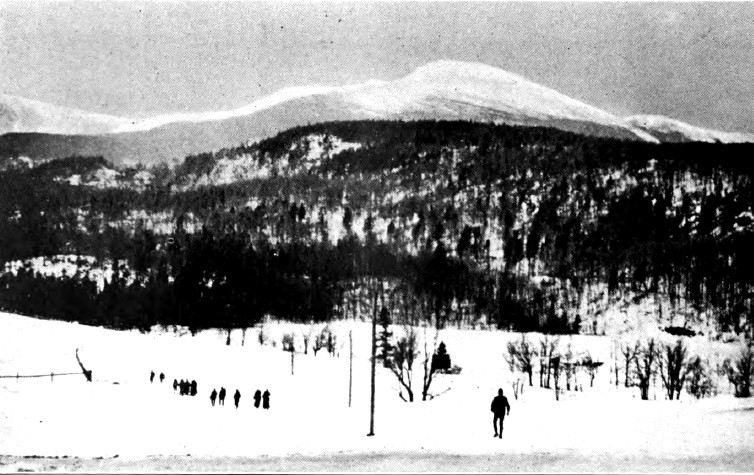

| VII MIDWINTER ON THE ROOF OF NEW ENGLAND IT was ten below zero and half-past six on

a February

morning. Not a breath of breeze stirred. In the Glen it was broad

daylight,

though not yet sunrise. The atmosphere was sparkling clear, and the

Great

Range, that formed the western wall of the little mountain valley,

stood

sharply white against a sky of intensest blue. On the summits of

Washington,

Adams, and Madison a pink blush stole across the snow. Sunrise had come

to the

upper world. A dozen men and women emerged from the

little inn,

buckled on their snowshoes, shouldered their pack-bags, and by twos and

threes

clattered across the hard-packed door-yard snow toward the big

mountain. The

call of the summit was not to be denied on such a morning. Could they

make it?

Easily enough — provided.

Legs and hearts and lungs could be

relied on in that party. For four days they had been tried out in minor

climbs.

Equipment adapted to the conditions of the place and season was not

lacking to

insure a safe success. Only a change in the weather could spoil the

day. Would

the weather hold? Would the wind rise later in the day? These were the

questions uppermost in their minds during the next two hours as they

plugged

stolidly up the first four miles of the old carriage road to the

Half-Way House

at timber-line. It was a picturesque bunch of humanity,

each member

clad as his or her whimsy led. It is well that it is stated that both

men and

women were in the party, for at a trifling distance, and out of earshot

of

their voices, this might not have been apparent to an onlooker.

Clothes, 't is

said, do not make the man, but on a winter mountaineering trip they

certainly

make the woman — shall

it be said — almost

like the man. On that same morning

Bostonians at home were muffling in furs to repel a cold that did not

push the

mercury down to the zero mark. In that. clear, crisp mountain air

scarce an ear

was covered, and mittened hands were likewise the exception. Once

across the

open flat and grinding upward in the sheltering timber, jackets and

sweaters

were opened one by one, then gradually peeled and consigned to the

packs. Even

at zero and below it can be a perspiry performance after the sun has

risen

above the Carter Range on such a windless morning. Trudge, trudge, trudge, trudge. It would

be a

monotonous and wearying chore, digging up those even grades, were it

not for

the little incidents of the way. Squirrels and rabbits, partridges and

foxes,

wild-cats even, have been that way before you and have left a record of

their

haste or leisure in the snow. The cheerful chickadees also are on hand,

and,

confident of your good-will, pause from their busy search for food long

enough

to throw you a contented "thee." Rounding a shoulder a break in the forest

opens a

vista upward toward the summit, and with that glimpse the spell is on

you more

firmly than ever. Your legs reach out more eagerly. The sight lifts

several

pounds from off your back. Soon the timber begins to shorten. There is

more

spruce and balsam and mountain ash, and less maple. You do not need an

aneroid

to tell you that you are getting up. Suddenly your head comes out into

the

open. The trees sink down to mere shrubs. A broad view north into the

valley of

the Androscoggin is spread out, and looking ahead along the road there

looms

the black bulk of the old toll-house at the four-mile turn. Timber-line

has

been reached. Of the forty-seven hundred feet of rise to make from Glen

to

summit, twenty-four hundred are behind.  Mount Washington in Winter The mere thought of climbing Mount

Washington in

winter is a horror to some. Indeed, it is not a jaunt to be undertaken

in any

careless spirit, or without a good knowledge of the mountain and its

moods, or

with anything short of good equipment. But it is not a fool's errand,

although

it is well to be careful in whom you confide your fondness for such

excursions

lest your sanity be questioned. Yet not a winter has passed these

twenty-five

years or more that has not seen more than one party on the summit of

New

England's highest mountain. Latterly it has become the Mecca of the

Dartmouth

(College) Outing Club boys for their annual winter trip, and some

members of

the Appalachian Mountain Club, and people from the near-by towns of

Gorham and

Berlin as well, make the ascent nearly every year. Clearly the crazy

ones are

on the increase. And there would be more yet if such days as that which

favored

the party from the Glen could be guaranteed. Winter ascents have been made on several

occasions

under conditions far from ideal, but no one who has ever experienced

the summit

in bad winter weather would willingly repeat it. Nothing is more

completely

calculated to take the joy out of life, judging from the tales of

those who

have lived through one of Mount Washington's angry winter fits. So far

all have

lived through, though there were some narrow escapes among the United

States

Signal Service men in the days when the Government maintained an

observation

station on the summit. Not a few, even in recent years, have been

unexpectedly

caught on the top by an on-rushing storm, and marooned there for a

night or

two, not an experience to be craved by any means. Although shelter may be obtained by

forcing an

entrance to one of the buildings, fuel is not abundant at two thousand

feet

above timber-line, food is likely to be scanty, and bedding wholly

wanting. To

be forced to spend a night there under such conditions as the Signal

Service

men experienced on one or two occasions would hardly be salubrious.

Fifty-nine

below zero was the coldest that they encountered, and once, even with a

red-hot

stove in a snugly sealed room, water froze a few feet from the fire.

Nor does

any one care to take rash chances in a place where the wind has been

known to

blow at a pace of one hundred and eighty miles an hour or more. Four of

us,

well-equipped men, are ready to testify that it is-.sufficiently rough

to be

caught there in a frost cloud when the temperature is as mild as twenty

degrees

above zero, and in a wind against which it is possible to stand and

walk. Suffice it to say that Mount Washington's

summit

weather in winter is most untrustworthy, and he who treats it casually

is but

foolhardy. Conditions in the neighboring valleys, or on the minor

mountains

roundabout, are no indication of those on top. All may be serene and

smiling

below, and yet a fearful battle of the elements be raging up above.

Timber-line

is the limit of safety. Before venturing beyond that the climber needs

to take

account of his stock of prudence, and the inexperienced one who

ventures farther

unguided will deserve what he gets.  Tuckerman Ravine and the walls of Of the three usual winter routes to the

summit

probably that by the carriage road is the one most used, largely

because it is

the one most accessible, with a hotel at its lower end, and a sled-road

open to

it throughout the winter from Gorham on the north. Figured from base to

summit

it is, indeed, the longest route, and the one most exposed as well,

with its

four miles of ramblings above the tree-line. Its miles do not count

for

fatigue, however, for the continuous panorama of the neighboring snowy

peaks

and black ravines make this anything but a tedious tramp. There can be

no denying

that it is a perilous route in winter, and the climber needs to assign

to one

eye at least the constant duty of watching the weather, which has a way

of

changing its mind for the worse without much muttered warning. To

escape to the

timber, once the ascent of Chandler Ridge has been undertaken, is no

easy

matter. Most old hands quit the carriage road half

a mile or

so above the Half-Way House to cut straight up the steep slopes along

the

telephone line. There are two advantages in this. It shortens the

distance by

about a mile by the elimination of a long detour which the road is

forced to

make for grade, a stretch that is always badly drifted, and sometimes

dangerously iced. It also affords a shorter avenue of escape into the

Gulf on

the west by Chandler Brook or the Six Husbands' Trail in case of need.

To

attempt to retreat on the east and south through Huntington and

Tuckerman

Ravines might be possible under some conditions, but would only be

attempted

probably as a last extremity, as it is no mean alpine stunt to descend

the

steep walls, especially those of Huntington. Undoubtedly the safest approach to the top

is that

which was used by the Signal Service men, up the cog railway from the

west. It

is also the shortest, being only three miles from Base Station to

summit, and

sheltered by the trees for more than half the distance. There is no

need to

take chances on the weather on this route. If it is unsuitable on the

summit

the climber knows it the minute his head comes out of the trees, and he

has but

to duck and retrace. It is furthermore one of the recognized retreats

to

safety for those arriving on the summit by other routes, and caught

there by

sudden changes, since, whatever the quarter from which the wind may

blow, the

great cone of the mountain furnishes a fairly good lee in the shelter

of which

it is possible to beat around until the rails are reached. The out with

this

approach is the remoteness of the Base Station of the railroad from

habitations,

being between six and seven miles from Crawfords in one direction, and

from

Bretton Woods in the other, over unbroken roads. That taken into

consideration

makes this route longer than the carriage road by a mile or more, and

it is far

less interesting. The sporty climb is through Tuckerman

Ravine, and it

is also a safe one relatively speaking. No prettier snowshoe tramp is

to be had

in all the mountains than that up to the floor of the ravine, whether

the route

be from the Glen by the Raymond Path, or the steeper way, from Pinkham

Notch

via Crystal Cascade. Moreover, Tuckerman Ravine is itself one of the

great

sights of the mountains at any season, but particularly in winter when

its

floor is packed deep in drifted snow, and its head wall, rising steeply

for

eight hundred feet, gleams with crust and ice. Even though turned back

at this

point by undesirable weather above, as the writer has been repeatedly,

it is

certain that no one will feel that the day was spent in vain. To climb that Tuckerman wall to the Alpine

Garden at

the foot of the cone is work that attracts the alpinist. If it be icy,

then

ice-axe, creepers, and even the rope are essential. At other times the

snow may

be soft enough to admit of kicking toe-holds up the entire distance,

but one

needs to be careful even then, for a head-first coast, or a pin-wheel

roll,

down that forty-five-degree wall could result seriously. The roll was

once

accomplished without mishap, quite unintentionally, it may be remarked,

but the

gentleman never volunteered to show companions on subsequent trips how

it was

done. Above the wall comes the cone, affording a lee against the north

and west

winds in all but the most boisterous weather, a stiff push of half a

mile. There are two other approaches to the

summit of Mount

Washington that have at times been followed by adventurous winter

parties. One

is up from Crawfords by the historic Bridle-Path over the Southern

Peaks.

Probably this is the most dangerous of all. The other is from Randolph

by way

of the Northern Peaks, not quite so hazardous, because of the more

frequent

opportunities for retreat, but sufficiently bad to be approached with

the

utmost caution. By the carriage road the Half-Way House is

the head

of snowshoe navigation and the beginning of creeper travel. Here, too,

it is

well to resume some of the clothing that the warming tramp up through

the

timber made superfluous. The last of the protecting scrub vanishes

here, and a

few rods more takes one around the Horn, and out to the open

snow-fields of a

distinctly alpine world. In truth these are the "Christall Hills" as

an early explorer called them. Across the forested depths of the Great

Gulf

rise Madison, Adams, Jefferson, and Clay, the Great Northern Peaks,

brilliant

in their snowy caps, their spruce-draped flanks slashed down with

ice-filled

slides. Washington's head is hidden behind the crest of Chandler Ridge

which

mounts above one in steep terraces. Should there be wind it will be

encountered at the

Horn. That it does blow there at times is amply testified to by the

densely

packed snow and by its graceful surface sculpturings. This morning it

was still,

and not a wind cloud could be detected on any hand. The northern

valleys lay

veiled in such a soft gray haze as is often seen in summer and referred

to as

"heat." Along the length of the Carter and Baldface Ranges on the

east this deepened to a smoky, purplish tone. Through the cols on

either side

of Clay white frost clouds gently rolled, pushed up from the west, only

to

dissipate on the edge of the Gulf under the bright glare of the morning

sun. Steadily the creepers crunched up the

steep slope of

the ridge. Slowly but surely Nelson Crag was reached and skirted,

bringing to

view the summit, now close at hand. By luncheon-time we were there, and

it was

all done as easily and as comfortably as would be possible on the

finest summer

day. More so in fact, for surely no one had suffered from heat, nor

from the

other extreme for that matter. Sitting in the sun to munch our

luncheon, with

backs against the hotel wall, it was with difficulty that we credited

the thermometer's

reading of four above zero just around the corner in the shade. Mount Washington's summit was first

ascended in

winter as long ago as 1858, when Ben Osgood, the old Glen House guide,

piloted

a deputy sheriff' up the carriage road for the purpose of making a

legal

attachment. Four years later three North Country men made the first

winter trip

in a sporting spirit, only to be imprisoned in the old Summit House for

two

days and nights by a violent storm. Their tale, coupled with that of

the

sheriff, who narrowly escaped from a frost cloud on his descent,

doubtless

served, for a time, to quiet any latent enthusiasm in others for such

an

excursion. And yet it is quite probable that men have more than once

since then

weathered equally bad conditions on the mountain without serious

distress. The modern garb of windproof outer

clothing over

light woolens, with face masks and hoods, makes it possible for a

healthy and

vigorous person to stand deeper frost and harder blows. This matter of

clothing and equipment has received careful study by the Appalachian

Mountain

Club's committees for many years, and much that is best in materials

and

patterns, be they in snowshoes and other appliances, or in raiment,

that are on

sale to-day, are the result of the experiments and severe testings of

the

Club's members. After the Weather Bureau's station on the

mountain

was established in 1870 the observers not infrequently entertained

winter

callers, and it was during this period that the first snow ascent by

women was

made, two daughters of Ethan Allen Crawford accompanying their brother

and

nephew up the cog railway. Thirty-two years later a Massachusetts woman

made

the top by the carriage road in February, escorted by a group of

stalwart

Appalachian men, and in recent years it has been no uncommon thing for

women to

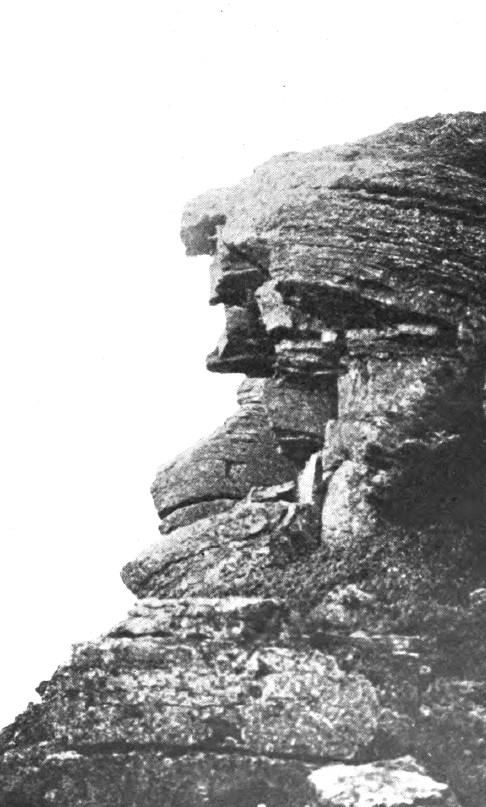

be in the climbing parties.  The Old Woman of Mount Madison Winter climbs to the summit have been made

from every

direction in the past twenty-five years, and there have been not a few

trying

experiences among those climbers, the details of which they have kept

much to

themselves. With the steadily increasing interest in winter sports,

and the

opening year by year of more and more hotels amid the mountains in

response to

this demand, it is altogether likely that the lure of the great white

cone will

reach hundreds where dozens have hitherto been tempted by it. Then will come the danger, that perhaps it

will be

the duty of the Government, in its capacity as proprietor of the

mountain, to

avert, by forbidding the ascent of the main summit during the winter

months

except under the pilotage of licensed guides. To any one who has ever

experienced those winter alpine scenes the fascination is perennially

irresistible. With steam-heated hotels, and with clothing adapted to

the

conditions, no privation or hardship is any longer involved, and every

beauty

and every thrill may be enjoyed, short of a climb to the top of the

big peak,

without incurring the smallest peril. |