|

1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

|

1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

WORKERS, QUEENS, AND DRONES

THE interior of a wasp's-nest is a very marvel

for neatness and order. It is kept perfectly clean, and probably the wasps

ventilate it through the hole in the bottom which in some nests forms the only

entrance, as bees ventilate the hive by fanning with their wings near the

opening.

THE interior of a wasp's-nest is a very marvel

for neatness and order. It is kept perfectly clean, and probably the wasps

ventilate it through the hole in the bottom which in some nests forms the only

entrance, as bees ventilate the hive by fanning with their wings near the

opening.

Certainly, captive wasps fan, just as captive bees do, and it is reasonable to suppose that this action is applied as a remedy for bad air.

The wasps, like the bees, have sentinels to watch at the entrance, and when a nest is disturbed these are the first to fly out and investigate the cause of the disturbance.

At their alarm the inmates of the nest rush forth, an angry swarm, ready to sting anything or anybody within reach.

Hornets have been known to work by moonlight, and captive wasps are unable to compose themselves to sleep if there is a light near them.

The workers do all the work of the hive, and live on friendly terms with one another and with the world in general, unless some one from the outside world alarms them and causes them to fear harm to their nest.

Wasps do not steal from one another as bees so often do, and different swarms do not fight, though once in a while there will arise bad blood between two members of a nest; then there will be a fierce combat very likely resulting in the death of one.

Generally, however, the wasps are friendly with one another, and when a worker flies home with her stomach full of honey she is willing to regurgitate the delicacy for the benefit of her relatives. She stands and puts forth a glistening drop from her mouth while two or three hungry sisters eagerly lap it up. Although the wasp's-nest has such a modest beginning it often attains quite lordly dimensions toward the end of the season, and contains many thousands of inhabitants.

For several weeks only workers are developed. Then into some of the larger cells, which, we have seen, are built later, unfertilised eggs are laid, the queen having the power to fertilise the eggs or not, as she pleases. From these unfertilised eggs drones are developed. Sometimes the drone combs are quite distinct from the worker combs, the cells in those being larger than the worker cells; and again, drone eggs are laid in the larger cells of the worker combs.

The drone is the male wasp. He is usually larger

than a worker, is more brightly coloured, has long, drooping antennae, and he

has no sting.

The drone is the male wasp. He is usually larger

than a worker, is more brightly coloured, has long, drooping antennae, and he

has no sting.

He is rather sluggish as compared with the workers, and likes to put his head down into an empty cell and stay there with only his tail visible - probably taking a nap.

Sometimes, however, he bestirs himself and helps to feed the larvae, going from cell to cell and popping food into each wide-open mouth.

At least, yellow-jacket drones have been seen to do this in captivity.

It is said the drone also keeps the vespiary clean, clearing away all rubbish and carrying out dead bodies.

The workers are undeveloped females that hatch from fertilised eggs. Usually they have not the power to lay eggs, though if the queen disappears some of the better developed of the workers sometimes lay eggs. These are never fertilised; and consequently produce nothing but drones.

Soon after the drone eggs are laid, the workers build yet larger cells than any yet constructed, and in each of these a fertilised egg is put. When it hatches, the careful nurses supply it with abundant food.

In its larger cell, with room to develop and plenty of nutriment, the insect becomes a perfect female, or queen.

The queen cells are not only larger than the others, but are also taller, the cap being built down farther below the edge of the cell.

The queen combs are very pretty with their snowy, rounded domes.

Often they are the last made, and therefore are the lowest combs in the nest. Frequently the lowest comb will be wholly devoted to queen cells, though sometimes they are found encircling other combs.

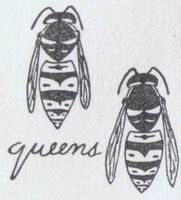

In time the queens emerge large and handsome.

They are bright in colour, and are marked differently from the other members of the nest. They are considerably larger than the drones, and can be recognised at a glance.

On sunny days they fly abroad, where they mate

with the drone. Each queen at that time receives a quantity of fertilising

material, which she stores in a receptacle that exists for that purpose, and

this material she uses at will to fertilise her eggs. The queens mate but once,

the supply they receive lasting as long as they live. Queens and drones spin

their own cocoons just as the workers do. Indeed, the development of the queens

and drones from egg to pupa, and from pupa to perfect insect or imago, is

essentially the same as the development of the workers.

On sunny days they fly abroad, where they mate

with the drone. Each queen at that time receives a quantity of fertilising

material, which she stores in a receptacle that exists for that purpose, and

this material she uses at will to fertilise her eggs. The queens mate but once,

the supply they receive lasting as long as they live. Queens and drones spin

their own cocoons just as the workers do. Indeed, the development of the queens

and drones from egg to pupa, and from pupa to perfect insect or imago, is

essentially the same as the development of the workers.

Several sizes of wasps may always be found in the same nest. Not only are the queens larger than the drones, and the drones larger than the workers, but queens, drones, and workers differ in size among themselves.

Some queens will be very large and beautiful, others will be much smaller. Drones differ in size even more than queens, some being large and well-developed, others being scarcely larger than workers.

Sometimes tiny little workers are seen in a nest, not more than half as large as the largest of their kind.

Very likely the food given causes this difference in size. Some larvae occupy larger cells and better positions in the combs than others, and probably receive more attention from the nurses.

The larvae that get the most food develop into the largest and finest wasps. Although the wasps' nests are so wonderfully constructed, they are not fitted to serve as winter habitations.

It is not necessary that they should be so used, for the history of a wasp colony is very different from that of a swarm of bees.

The worker bees remain alive through the winter, and the same hive is densely populated year after year.

Not so with the wasps. At the approach of cold weather they desert their nests. No more combs are built, and even the eggs and larvae already in the cells are abandoned.

Winter is coming, and with the first severe cold all drones and workers must perish.

Meantime, all thought of work and of home forgotten, the wasps fly about, often in large numbers, visiting the fall flowers, eating the ripe fruit, getting into houses, making nuisances of themselves, and having a good time generally.

The French naturalist Réaumur says that the wasps not only abandon their larvae at approach of cold weather, but that they drag them out and ruthlessly kill them.

This does not seem to be true of American wasps. They are content to leave their helpless young to the mercy of the frost, which is perhaps less merciful than the apparently cruel massacre of Réaumur’s wasps.

The young queens having power to resist the cold, crawl into some cranny, where they lie apparently lifeless, with their legs and wings folded about them, and await the coming of spring. Even in this state they can sting, as more than one luckless experimenter has learned to his cost.

Some people are afraid to take a wasp's nest into the house in the fall of the year, believing it to be full of dormant wasps that only need the genial warmth of the house to come to life and rush forth intent on making it lively for their entertainers. But this is not the case. The fall nest can be safely handled, as it is empty of living wasps.

Very soon the interior of a nest abandoned by the great mass of inhabitants becomes unfit for the habitation of the hibernating queens.

It becomes damp and mouldy inside, and is taken possession of by all sorts of vermin. Moreover, the fierce winter blasts blow these delicate fabrics to pieces, so that it is usually impossible to find a last year's wasp-nest, no matter how plentiful the nests may have been.

On rare occasions a nest in a very sheltered dry spot may escape destruction, and it is possible that queens may occasionally winter in these nests, though such an occurrence is a rare exception, if it ever happens.

Although it is within comparatively recent times that the habits of the social wasps have been scientifically studied, yet the ancients were not unobservant of these interesting insects.

Indeed, Aristotle, in his “History of Animals,” has given a very admirable account of the nests and the habits of the wasps. He describes their hexagonal cells, which he compared to those of bees, adding that they are not formed of wax, but of a web-like membrane, made of the bark of trees. He also describes the young in the cells, and tells us that in his time the wasps were so harmful to the bees that the bee fanciers caught them in pans in which they had placed pieces of meat. When many had collected in the pan it was covered and set on the fire.

Wasps are still fond of bees and when able will catch them and carry them as food to their nests. They are very fond of honey, so no wonder the honey-laden bee should be a tempting morsel, combining as it does both honey and juicy insect food.

Aristotle accurately describes the queen wasps and the workers. He also gives a clear and accurate account of nest-making, the rearing of workers first, and later of the mother wasps, and he describes the abandonment of the nest at the approach of winter, telling us that only the mothers survive to start the nest anew next year.

Indeed, he gives so good and so accurate an account of the whole history of the wasps, that modern writers have added but little new information.