CHAPTER III

ACROSS YUNNAN

My

departure was set for the 8th of April, and by

half-past four of that morning the coolies, marshalled by the hong man, were at

the door; but it was after nine before we were really under way. It is always a

triumphant moment when one's caravan actually starts; there have been so many

times when starting at all seemed doubtful. Mine looked quite imposing as it

moved off, headed by Mr. Stevenson on his sturdy pony, I following in my chair,

while servants and coolies straggled on behind, but, as usual, something was

missing. This time it was one of the two soldiers detailed by the Foreign

Office to accompany me the first stages of my journey. We were told he would

join us farther on. Fortunately Mr. Stevenson was up to the wiles of the

native, and he at once scented the favourite device for two to take the

travelling allowance, and then, by some amicable arrangement, for only one to

go. So messengers were sent in haste to look up the recreant, who finally

joined us with cheerful face at the West Gate, which we reached by a rough path

outside the north wall.

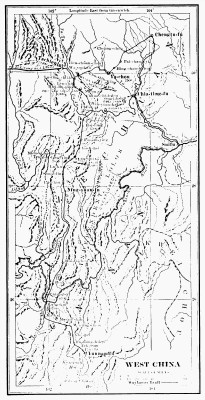

WEST CHINA

Here I bade Mr. Stevenson good-bye, and turned my

face away from the city. Once more I was on the "open

road." Above me shone the bright sun of Yunnan, before me lay the long

trail leading into the unknown. Seven hundred miles of wild mountainous

country, six weeks of steady travelling lay between me and Chengtu, the great

western capital. The road I planned to follow would lead nearly due north at first,

traversing the famous Chien-ch'ang valley after crossing the Yangtse. But at

Fulin on the Ta Tu I intended to make a dιtour to the west as far as Tachienlu,

that I might see a little of the Tibetans even though I could not enter Tibet.

I did not fear trouble of any sort in spite of a last letter of warning

received at Hong Kong from our Peking Legation, but there was just enough of a

touch of adventure to the trip to make the roughnesses of the way endurable.

Days would pass before I could again talk with my own kind, but I was not

afraid of being lonely. "The scene was savage, but the scene was

new," and the hours would be filled full with the constantly changing

interests of the road, and as I looked at my men I felt already the comradeship

that would come with long days of effort and hardship passed together. These

men of the East Turk, Indian, Chinese, Mongol are much of a muchness, it

seems to me; pay them fairly, treat them considerately, laugh instead of storm

at the inevitable mishaps of the way, and generally they will give you

faithful, willing service. It is only when they have been spoiled by

overpayment, or by bullying of a sort they do not

understand, that the foreigner finds them exacting and untrustworthy. And the

Chinese is an eminently reasonable man. He does not expect reward without work,

and he works easily and cheerfully. But as yet he was to me an unknown

quantity, and I looked over my group of coolies with some interest and a little

uncertainty. They were mostly strong, sound-looking men; two or three were

middle-aged, the rest young. No one looked unequal to the work, and no one

proved so. All wore the inevitable blue cotton of the Chinese, varying with

wear and patching from blue-black to bluish-white, and the fashion of the dress

was always the same; short, full trousers, square-cut, topped by a belted shirt

with long sleeves falling over the hands or rolled up to the elbow according to

the weather. About their heads they generally twisted a strip of cotton, save

when blazing sun or pouring rain called for the protection of their wide straw

hats covered with oiled cotton. Generally they wore the queue tucked into the

girdle to keep it out of the way, but occasionally it was put to use, as, for

example, if a man's hat was not at hand to ward off the glare of the sun, he

would deftly arrange a thatch of leaves over his eyes, binding it firm with his

long braid of black hair. On their feet they wore the inevitable straw sandal

of these parts. Comfortable for those who know how to wear them, cheap even

though not durable (they cost only four cents

Mexican the pair), and a great safeguard against slipping, they seemed as

satisfactory footwear as the ordinary shoes of the better-class Chinese seemed

unsatisfactory. Throughout the East it is only the barefooted peasant or the

sandalled mountaineer who does not seem encumbered by his feet. The felt shoe

of the Chinese gentleman and the flapping, heelless slipper of the Indian are

alike uncomfortable and hampering. Nor have Asiatics learned as yet to wear

proper European shoes, or to wear them properly, for they stub along in badly

cut, ill-fitting things too short for their feet. Why does not the shoemaker of

the West, if he wishes to secure an Eastern market, study the foot of the

native, and make him shoes suited to his need?

Our order of march through Yunnan varied little from

day to day. We all had breakfast before starting at about seven, and we all had

much the same thing, tea and rice, but mine came from the coast; the coolies

bought theirs by the way. At intervals during the forenoon we stopped at one of

the many tea-houses along the road to give the men a chance to rest and smoke

and drink tea. Sometimes I stayed in my chair by the roadside; more often I

escaped from the noise and dirt of the village to some spot outside, among the

rice- and bean-fields, where the pony could gather a few scant mouthfuls of

grass while I sat hard-by on a turf balk and enjoyed the quiet and clean air.

Of course I was often found out and followed by the village-folk, but their

curiosity was not very offensive. Generally they squatted down in a semi-circle

about me, settling themselves deliberately to gaze their fill. If they came too

near I laughed and waved them back, and they always complied good-naturedly.

The little children were often really quite charming under the dirt, but until

they had learned to wash their faces and wipe their noses I must confess I

liked them best at a distance.

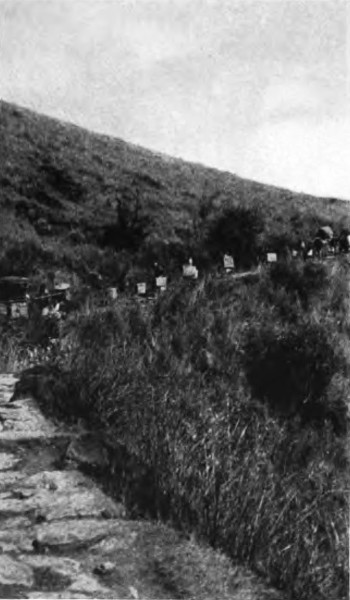

MY CARAVAN

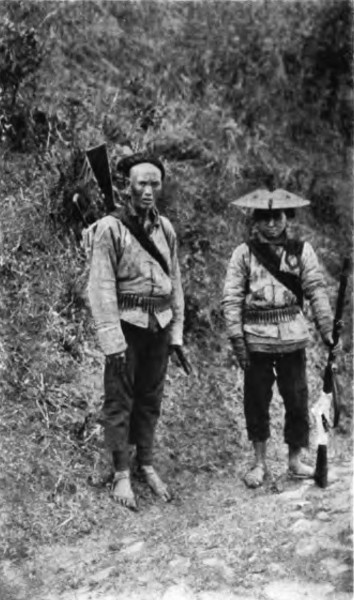

THE MILITARY ESCORT

ON A YUNNAN ROAD

At noon we stopped at a handy inn or tea-house for tiffin and a long rest. I was ordinarily served at

the back of the big eating-room open to the street in as dignified seclusion as

my cook could achieve. Rice again, with perhaps stewed fowl or tinned beef, and

a dessert of jam and biscuit, usually formed my luncheon, and dinner was like

unto it, save that occasionally we succeeded in securing some onions or

potatoes. The setting-forth of my table with clean cloth and changes of plates

was of never-failing interest to the crowds that darkened the front of the eating-house,

and excitement reached a climax when the coolie, whom my cook had installed as

helper, there is no Chinese too poor to lack some one to do his bidding,

served Jack his midday meal of rice in his own dish. Then men stood on tiptoe

and children climbed on each other's shoulders to see a dog fed like the

Chinese equivalent of Christian. They never seemed

to begrudge him his food; on the contrary, they often smiled approvingly. We

were thousands of miles away from the famine-stricken regions of eastern China,

and through much of the country where I journeyed I saw almost no beggars or

hungry-looking folk. In the afternoon we stopped as before at short intervals

at some roadside tea-house, for the coolies generally expect to rest every

hour.

Our day's stage usually ended in a good-sized town. I

should have preferred it otherwise, for there is more quiet and freedom in the

villages. But my coolies would have it so; they liked the stir and better fare

of the towns, and the regular stages are arranged accordingly. Our entrance was

noisy and imposing. My coming seemed always expected, for as by magic the

narrow streets filled with staring crowds. Through them the soldiers fought a

way for my chair, borne at smart pace by the coolies all shouting at the top of

their voices. I tried to cultivate the superior impassiveness of the Chinese

official, but generally the delighted shrieks of the children at the sight of

Jack at my feet, and his gay yelps in response, "upset the apple

cart." There was a rush to see the "foreign dog." I gripped him

tighter and only breathed freely when with a sharp turn to right or left my

chair was lifted high over a threshold and borne through the inn door into the

courtyard, the crowd in no wise baffled swarming at our heels, sometimes not even stopping at the entrance to the inner

court, sacred (more or less) to the so-called mandarin rooms, the best rooms of

the place. I could not but sympathize with the innkeeper, the order of his

establishment thus upset, but he took it in good part; perhaps the turmoil had

its value in making known to the whole world that the wandering foreigner had

bestowed her patronage upon his house. I am sure he had some reward in the many

cups of tea drunk while the crowd lingered on the chance of another sight of

the unusual visitor. Anyway we were always made welcome, and no objections were

offered when my men took possession of the place in very unceremonious fashion,

as it seemed to me, filling the court with their din, blocking the ways with

the chairs and baskets, seeking the best room for me, and then testing the door

and putting things to rights after a fashion, while the owner looked on in

helpless wonder.

In the villages one stepped directly from the road

into a large living-room, kitchen, and dining-room in one, and out of this

opened the places for sleeping. The inns in the towns are built more or less

after one and the same pattern. Entrance is through a large restaurant open to

the street, and filled with tables occupied at all hours save early dawn with

men sipping and smoking. From the restaurant one passes into a stone-paved

court surrounded usually by low, one-story

buildings, although occasionally there is a second story opening into a

gallery. Here are kitchens and sleeping-rooms, while store-rooms and stables

are tucked in anywhere. In the largest inns there is often an inner court into

which open the better rooms.

While the cook bustled about to get hot water, and

the head coolie saw to the setting-up of my bed, I generally went with the

"ma-fu," or horse boy, to see that the pony was properly cared for.

Usually he was handy, sometimes tethered by my door, often just under my room,

once overhead. Meanwhile the coolies were freshening themselves up a bit after

the day's work. Sitting about the court they rinsed chest and head and legs

with the unfailing supply of hot water which is the one luxury of a Chinese

inn. I can speak authoritatively on the cleanliness of the Chinese coolie, for

I had the chance daily to see my men scrub themselves. Their cotton clothing

loosely cut was well ventilated, even though infrequently cleansed, and there

hung about them nothing of the odour of the great unwashed of the Western

world. I wish one could say as much for the inns, but alas, they were

foul-smelling, one and all, and occasionally the room offered me was so filthy

that I refused to occupy it, and went on the war-path for myself, followed by a

crowd of perplexed servants and coolies. Almost always I found a loft or a

stable-yard that had at least the advantage of plenty of fresh air, and without demur my innkeeper made me free of it, although I expect

it cut him to the heart to have his best room so flouted.

Generally I went to bed soon after dinner; there was

nothing else to do, for the dim lantern light made reading difficult, and

anyway my books were few. But while the nights were none too long for me, the

Chinese, like most Asiatics, make little distinction between day and night.

They sleep if there is nothing else to do, they wake when work or pleasure

calls, and it was long after midnight when the inn settled itself to rest, and

by four o'clock it was again awake, and before seven we were once more on the

road.

In Yunnan, or "South of the Clouds," as the

word signifies, you are in a land of sunshine, of wild grandeur and beauty, of

unfailing interest. Its one hundred and fifty-five thousand square miles are

pretty much on end; no matter which way you cross the country you are always

going up or going down, and the contrasts of vegetation and lack of it are just

as emphatic; barren snow-topped mountains overhang tiny valleys, veritable gems

of tropical beauty; you pass with one step from a waste of rock and sand to a

garden-like oasis of soft green and rippling waters. Yunnan's chequered history

is revealed in the varied peoples that inhabit the deep valleys and narrow

river banks. Nominally annexed to the empire by Kublai Khan, the Mongol, in the

thirteenth century, ever since the Chinese people

have been at work peacefully and irresistibly making the conquest real, and now

they are found all over the province, as a matter of course occupying the best

places. But they have not exterminated the aborigines, nor have they

assimilated them to any degree. To-day the tribes constitute more than one half

the population, and an ethnological map of Yunnan is a wonderful patchwork, for

side by side and yet quite distinct, you find scattered about settlements of

Chinese, Shans, Lolos, Miaos, Losus, and just what some of these are is still

an unsolved riddle. To add to the confusion there is a division of religions

hardly known elsewhere, for out of the population of twelve millions it is

estimated that three or four millions are Mohammedans. To be sure, they seem

much like the others, and generally all get on together very well, for Moslem

pride of religion does not find much response with the practical Chinese, and

the Buddhist is as tolerant here as elsewhere. But the Mohammedan rebellion of

half a century ago has left terrible memories; then add to that the ill-feeling

between the Chinese and the tribesmen, and the general discontent at the

prohibition of poppy-growing, and it is plain that Yunnan offers a fine field

for long-continued civil disorder with all the possibility of foreign

interference.

The early hours of our first day's march led us along

the great western trade route, and we met scores of

people hurrying towards the capital, mostly coolies carrying on their backs, or

slung from a bamboo pole across their shoulders, great loads of wood, charcoal,

fowls, rice, vegetables. Every one was afoot or astride a pony, for there was

nothing on wheels, not even a barrow. The crowd lacked the variety in colour

and cut of dress of a Hindu gathering; all had black hair and all wore blue

clothes, and one realized at once how much China loses in not having a

picturesque and significant head covering like the Indian turban. But the faces

showed more diversity both in hue and in feature than I had looked for. In

America we come in contact chiefly with Chinese of one class, and usually from

the one province of Kwangtung. But the men of Yunnan and Szechuan are of a

different type, larger, sturdier, of better carriage. It takes experience

commonly to mark differences in face and expression among men of an alien race,

and to the Asiatic all Europeans look much alike, but already I was discerning

variety in the faces I met along the trail, and they did not seem as unfamiliar

to me as I had expected. I was constantly surprised by resemblances to types

and individuals at home. One of my chair coolies, for example, a young,

smooth-faced fellow, bore a disconcerting likeness to one of my former

students. But fair or dark, fine-featured or foul, all greeted me in a friendly

way, generally stopping after I had passed to ask my coolies

more about me. My four-bearer chair testified to my standing, and my men,

Eastern fashion, glorified themselves in glorifying me. I was a

"scholar," a "learned lady," but what I had come for was

not so clear. A missionary I certainly was not. Anyway, as a mere woman I was

not likely to do harm.

The road after crossing the plain entered the hills,

winding up and down, but always paved with cobbles and flags laid with infinite

pains generations ago, and now illustrating the Chinese saying of "good

for ten years, bad for ten thousand." It was so hopelessly out of repair

that men and ponies alike had to pick their way with caution. Long flights of

irregular and broken stone stairs led up and down the hillsides over which my

freshly shod pony slipped and floundered awkwardly, and I always breathed a

sigh of relief when a stretch of hard red earth gave a little respite. It was

neither courage nor pride that kept me in the saddle, but the knowledge that

much of the way would be worse rather than better, and I would wisely face it

at the outset. If it got too nerve-racking I could always betake myself to my

chair and, trusting in the eight sturdy legs of my bearers, abandon myself to

enjoying the sights along the way.

Our first day's halt for tiffin was at the small hamlet

of P'u chi. The eating-house was small and crowded, and my cook set my table

perforce in the midst of the peering, pointing

throng. I was the target of scores of black eyes, and I felt that every

movement was discussed, every mouthful counted. As a first experience it was a

little embarrassing, but the people seemed good-humoured and very ready to fall

into place or move out of the way in obedience to my gestures when I tried to

take some pictures, not too successfully. Here for a moment I was again in

touch with my own world, as a runner, most thoughtfully sent by Mr. Stevenson

with the morning's letters, overtook me. According to arrangement he had been

paid beforehand, but not knowing that I knew that, he clamoured for more. The

crowd pressed closer to listen to the discussion, and grinned with a rather

malicious satisfaction when the man was forced to confess that he had already

received what they knew was a generous tip. Chinese business instinct kept them

impartial, even between one of their own people and a foreigner.

That night we stopped, after a stage of some sixty

li, about nineteen miles, at Erh-tsun, a small, uninteresting village. The inn

was very poor, and I would have consoled myself by thinking that it was well to

get used to the worst at once, only I was not sure that it was the worst. My

room, off the public gathering place, had but one window looking directly on

the street. From the moment of my arrival the opening was filled with the faces

of a staring, curious crowd, pushing each other,

stretching their necks to get a better view. My servants put up an oiled cotton

sheet, but it was promptly drawn aside, so there was nothing for me to do but

wash, eat, and go to bed in public, like a royal personage of former times.

It was a beautiful spring morning when we started the

next day. We were now among the mountains, and much of our way led along barren

hillsides, but the air was intoxicating, and the views across the ridges were

charming. At times we dropped into a small valley, each having its little group

of houses nestling among feathery bamboos and surrounded by tiny green fields.

Dogs barked, children ran after us, men and women stopped for a moment to smile

a greeting and exchange a word with our coolies. As a rule, the people looked comfortable

and well fed, but here and there we passed a group of ruined, abandoned hovels.

The explanation varied. Sometimes the ruin dated back more than a generation to

the terrible days of the Mohammedan rebellion. In other cases the trouble was

more recent. The irrigating system had broken down, or water was scant, or more

frequently the cutting-off of the opium crop had driven the people from their

homes. But in general there was little tillable land that was unoccupied. In

fact, the painstaking effort to utilize every bit of soil was tragic to

American eyes, accustomed to long stretches of countryside awaiting the plough.

At the close of the troubles that devastated the

province during the third quarter of the nineteenth century it is said that the

population of Yunnan had fallen to about a million, but now, owing in part to

the great natural increase of the Chinese, and in part to immigration chiefly

from overpopulated Szechuan and Kwei-chou, it is estimated at twelve million.

At any rate, those who know the country well declare there is little vacant

land fit for agriculture, that the province has about as many inhabitants as it

can support, and can afford no relief to the overcrowded eastern districts.

This is a thing to keep in mind when Japan urges her need of Manchuria for her

teeming millions.

We stopped for tiffin at Fu-ming-hsien, a

prosperous-looking town of some eight hundred families. As usual, I lunched in

public, the crowd pressing close about my table in spite of the efforts of a

real, khaki-clad policeman; but it was a jolly, friendly crowd, its interest

easily diverted from me to the dog. Here we changed soldiers, for this was a

hsien town, or district centre. Those who had come with me from Yunnan-fu were

dismissed with a tip amounting to about three cents gold a day each. They

seemed perfectly satisfied. It was the regulation amount; had I given more they

would have clamoured for something additional. That afternoon we stopped for a

long rest at a tiny, lonely inn, perched most picturesquely on a spur of the

mountain. I sat in my chair while the coolies drank

tea inside, and a number of children gathered about me, ready to run if I

seemed dangerous. Finally one, taking his courage in both hands, presented me

with the local substitute for candy, raw peas in the pod, which I nibbled and

found refreshing. In turn I doled out some biscuits, to the children's great

delight, while fathers and mothers looked on approvingly. The way to the heart

of the Chinese is not far to seek. They dote on children, and children the

world over are much alike. More than once I have solved an awkward situation by

ignoring the inhospitable or unwilling elders and devoting myself to the little

ones, always at hand. Please the children and you have won the parents.

We stopped that night at Chκ-pei, a small town lying

at an elevation of about six thousand feet. My room, the best the inn afforded,

was dirty, but large and airy. On one side a table was arranged for the

ancestral family worship, and I delayed turning in at night to give the people

a chance to burn a few joss sticks, which they did in a very matter-of-fact

fashion, nowise disturbed at my washing-things, which Liu, the cook, had set

out among the gods.

Our path the next day led high on the mountain-side

and along a beautiful ridge. We stopped for an early rest at a little walled

village, Jee-ka ("Cock's street"), perched picturesquely on the top

of the hill. Later we saw a storm advancing across the mountains, and before we could reach cover the clouds broke over our

heads, drenching the poor coolies to the skin, but they took it in good part,

laughing as they scuttled along the trail. The rain kept on for some hours, and

the road was alternately a brook or a sea of slippery red mud; the pony, with

the cook on his back, rolled over, but fortunately neither was hurt; coolies

slid and floundered, and the chair-men went down, greatly to their confusion,

for it is deemed inexcusable for a chair-carrier to fall. Toward the end of the

day it cleared and the bright sun soon dried the ways, and we raced into

Wu-ting-chou in fine shape, the coolies picking their way deftly along the

narrow earth balks that form the highway to this rather important town. Our

entrance was of the usual character, a cross between a triumphal procession and

a circus show, people rushing to see the sight, children calling, dogs

barking, my men shouting as they pushed their way through the throng, while I

sat the observed of all, trying to carry off my embarrassment with a benevolent

smile. I am told that the interest of a Chinese crowd usually centres on the

foreigners' shoes, but in my case, when the gaze got down to my feet, Jack was

mostly there to divert attention.

Rain came on again in the night and kept us in

Wu-ting-chou over the next day. The Chinese, with their extraordinary

adaptability, can stand extremes of heat and cold

remarkably well. Hence they are good colonizers, able to work in Manchuria and

Singapore, Canada and Panama. But rain they dislike, and a smart shower is a

good excuse for stopping. Fortunately for all, the inn was unusually decent.

Steps led from the street into an outer court, behind which was a much larger

second court, surrounded on all sides by two-story buildings. My room on the

upper floor had beautiful views over the town, more attractive at close range

than most Chinese towns. The temples and yamen buildings were exceptionally

fine, while the houses, of sun-dried brick of the colour of the red soil of

Yunnan, had a comfortable look, their tip-tilted tiled roofs showing

picturesquely among the trees.

I spent the rainy forenoon in writing and in leaning

over the gallery to watch the life going on below. After the first excitement

people went about their business undisturbed by my presence. At one side

cooking was carried on at a long, crescent-shaped range of some sort of cement,

and containing half a dozen openings for fires. Above each fire was a

bowl-shaped depression in the range, and into this was fitted a big iron pot.

The food of the country is generally boiled, and is often seasoned with a good

deal of care. Barring the lack of cleanliness, the chief objection to the

cooking of the peasant-folk is the failure to cook thoroughly. The Chinese are

content if the rice and vegetables are cooked

through; they do not insist, as we do, that they be cooked soft. In the smaller

inns my men prepared their food themselves, and some showed considerable skill.

One soldier in particular was past-master in making savoury stews much

appreciated by the others.

Wu-ting-chou being a place designated for the payment

of an instalment of wages, and also the time having come for pork money, my

coolies had a grand feast, after which they devoted themselves to gambling away

their hard-earned money in games of "fan t'an." As they played

entirely among themselves the result was that some staggered the following day

under heavy ropes of cash, while others were forced to sell their hats to pay

for their food. I could only hope that the next pay-day would mean a

readjustment of spoils.

In the afternoon it cleared, and I went out in my

chair, escorted by two policemen, to a charming grove outside the walls, where

I rested for a time in a quiet nook, enjoying the views over the valley and

thankful to get away from the din of the inn. Curling up, I went fast asleep,

to wake with an uncomfortable sense of being watched; and sure enough, peering

over the top of the bank where I was lying were two pairs of startled black

eyes. I laughed, and thereupon the owners of the eyes, who had stumbled upon me

as they came up the hill, seated themselves in front of me

and began to ply me with questions, to which I could only answer with another

laugh; so they relapsed into friendly silence, gingerly stroking Jack while

they kept a watchful eye on me. What does it matter if words are lacking, a

laugh is understood, and will often smooth a way where speech would bring

confusion. Once, years ago in Western Tibet, I crossed a high pass with just

one coolie, in advance of my caravan. Without warning we dropped down into a

little village above the Shyok. Most of the people had never before seen a

European. I could not talk with them nor they with my coolie, for he came

from the other side of the range, nor he with me. But I laughed, and every

one else laughed, and in five minutes I was sitting on the grass under the

walnut trees, offerings of flowers and mulberries on my lap, and while the

whole population sat around on stone walls and house roofs, the village head

man took off my shoes and rubbed my weary feet.

When I emerged from my retreat I found that a priest

from the neighbouring temple had come to beg a visit from me. It turned out to

be a Buddhist temple on the usual plan, noteworthy only for a rather good

figure of Buddha made of sun-dried clay and painted. The priest was inclined to

refuse a fee, saying he had done nothing, but he was keen to have me take some

pictures.

TEMPLE GATEWAY

TEMPLE CORNER

WU-TING-CHOU

The next three days our path led us across the mountains separating the Yangtse and Red River basins. We

were now off the main roads; villages and travellers were few. To my delight we

had left for a time the paved trails over which the pony scraped and slipped;

the hard dirt made a surer footing, and it was possible to let him out for a

trot now and then. The start and finish of the day were usually by winding

narrow paths carried along the strips of turf dividing the fields or over the

top of a stone wall. I learned to respect both the sure-footedness of the

Yunnan pony and the thrift of the Yunnan peasant who wasted no bit of tillable

land on roads. From time to time we crossed a stone bridge, rarely of more than

one arch, and that so pointed that the ponies on the road, which followed

closely the line of the arch, clambered up with difficulty only to slide

headlong on the other side. The bridges of these parts are very picturesque,

giving an added charm to the landscape, in glaring contrast to the hideous,

shed-like structures that disfigure many a beautiful stream of New England.

Our way led alternately over barren or pine-clad

hills, showing everywhere signs of charcoal burners, or through deep gorges, or

dipped down into tiny emerald valleys. At one point we descended an

interminable rock staircase guarded by soldiers top and bottom. Formerly this

was a haunt of robbers, but now the Government was making a vigorous effort to

insure the safety of traffic along this way. Our stay

that night was in a tiny hamlet, and a special guard was stationed at the door

of the inn to defend us against real or fancied danger from marauders.

It was still early in April, but even on these high

levels the flowers were in their glory, and each day revealed a new wonder.

Roses were abundant, white and scentless, or small, pink, and spicy, and the

ground was carpeted with yellow and blue flowers. From time to time we passed a

group of comfortable farm buildings, but much of the country had a desolate

look and the villages were nothing more than forlorn hamlets, and once we

stopped for the night in a solitary house far from any settlement. A week after

leaving Yunnan-fu we entered the valley of the Tso-ling Ho, a tributary of the

Great River, and a more fertile region. As I had been warned, the weather

changed here, and for the next twenty-four hours we sweltered in the steamy

heat of the Yangtse basin. From now on, there was no lack of water. On all

sides brooks large and small dashed down, swelling the Tso-ling almost to the

size of the main river itself. At one spot, sending the men on to the village,

I stopped on the river bank to bathe my tired feet, and was startled by the

passing of a stray fisherman, but he seemed in no wise surprised, and greeting

me courteously went on with his work. China shares with us the bad fame of

being unpleasantly inquisitive. Would the rural American, happening upon a Chinese woman, an alien apparition from her smoothly

plastered hair to her tiny bound feet, by the brookside in one of his home

fields, have shown the same restraint?

At five o'clock that same day we reached the ferry

across the Yangtse, too late to cross that night. I was hot and weary after a

long march, and the only place available in the village of Lung-kai was a

cramped, windowless hole opening into a small, filthy court, the best room of

the inn being occupied by a sick man. Through an open doorway I caught a

glimpse into a stable-yard well filled with pigs. On one side was a small,

open, shrine-like structure reached by a short flight of steps. In spite of the

shocked remonstrances of my men I insisted on taking possession of this; the

yard, though dirty, was dry, and at least I was sure of plenty of air. Fresh

straw was spread in the shrine and my bed set up on it; the pigs were given my

pony's stable, as I preferred his company to theirs; and I had an unusually

pleasant evening, spite of the fact that the roofs of the adjoining buildings

were crowded with onlookers, mostly children, until it grew too dark for them

to see anything.

We crossed the Yangtse the next day on a large

flat-bottomed boat into which we all crowded higgledy-piggledy, the men and

their loads, pony and chairs. The current was so swift that we were carried

some distance downstream before making a landing. At

this point, and indeed from Tibet to Suifu, the Yangtse is, I believe,

generally known as the Kinsha Kiang, or "River of Golden Sand." The

Chinese have no idea of the continuing identity of a river, and most of theirs

have different names at different parts of their course, but in this case there

is some reason for the failure to regard the upper and the lower Yangtse as one

and the same stream, for at Suifu, where the Min joins the Yangtse, it is much

the larger body of water throughout most of the year, and is generally held by

the natives to be the true source of the Great River. Moreover, above the

junction the Yangtse is not navigable, owing to the swift current and

obstructing rocks, while the Min serves as one of China's great waterways,

bearing the products of the famous Chengtu plain to the eastern markets.

After leaving the ferry we followed for some miles

the dry bed of a river whose name I could not learn. The scene was desolate and

barren in the extreme, nothing but rock and sand; and had it not been cloudy

the heat would have been very trying. But we were now among the Cloud

Mountains, where the bright days are so few that it is said the Szechuan dogs

bark when the sun comes out. After a short stop at a lonely inn near a trickle

of a brook we turned abruptly up the mountain-side, by a zigzag trail so steep

that even the interpreter was forced to walk. As I toiled wearily upward, I

looked back to find my dog riding comfortably in my

chair. Tired and hot, he had barked to be taken up. The coolies thought it a

fine joke, and when I whistled him down they at once put him back again,

explaining that it was hard work for short legs. At one of the worst bits of

the trail we met some finely dressed men on horseback, who stared in a superior

way at me on foot. The Chinese sees no reason for walking if he has a chair or

pony. What are the chair and the pony for? They must lack imagination, or how

can they ride down the awful staircases of a West China road, the pony plunging

from step to step under his heavy load? I doubt if they realize either the

pony's suffering or the rider's danger. I did both, and so I often walked.

After a climb of three thousand feet we came out on a wide open plateau,

beautifully cultivated, which we crossed to our night stopping-place,

Chiang-yi, nearly seven thousand feet above sea level.

We started the next morning in the rain, which kept

up pretty much all day. The country through which we now passed was rather bare

of cultivation and of inhabitants, but the wealth and variety of flowers and

shrubs more than made amends. Nowhere have I seen such numbers of flowering

shrubs as all through this region, a few known to me, but most of them quite

new. It was with much gratification that I learned at a later time of the

remarkable work done in connection with the Arnold Arboretum near Boston in seeking out and bringing to America

specimens of many of China's beautiful trees and plants. At the head of one

small valley we passed a charming temple half buried in oleanders and

surrounded by its own shimmering green rice-fields, and a little farther on we

came to a farmhouse enclosed in a rose hedge some twelve feet high and in full

bloom. There was no sign of life about, and it might have served as the refuge

of the Sleeping Princess, but a nearer inspection would probably have been

disillusioning.

We stopped that night at Ho-k'ou, a small place of

which I saw little, for the heavy rain that kept us there over a day held me a

prisoner in the inn. I had a small room over the pony's stable, and I spent the

forenoon writing to the tune of comfortable crunching of corn and beans. The

rest of the day I amused myself in entertaining the women of the inn with the

contents of my dressing-case, and when it grew cold in my open loft I joined

the circle round the good coal fire burning in a brazier in the public room.

Every one was friendly, and persistent, men and women alike, in urging me to

take whiffs from their long-stemmed tobacco pipes. All smoke, using sometimes

this long-stemmed, small-bowled pipe, and sometimes the water pipe, akin in

principle to the Indian hubble-bubble. In this part of Szechuan I saw few

smoking cigarettes, but thanks to the untiring efforts

of the British American Tobacco Company, they are fast becoming known, and my

men were vastly pleased when I doled some out at the end of a hard day.

From Ho-k'ou it was a two days' journey to

Hui-li-chou, the first large town on my trip. The scenery was charmingly

varied. At times the trail led along high ridges with beautiful glimpses down

into the valleys, or affording splendid views to right and left, to the

mysterious, forbidden Lololand to the east, and to the unsurveyed country

beyond the Yalung, west of us, or again it dropped to the banks of the streams,

leading us through attractive hamlets buried in palms and bamboo, pines and

cactus, while the surrounding hillsides were white or red with masses of

rhododendron just coming into flower. Entering one village I heard a sound as

of swarming bees raised to the one hundredth power. On inquiry it turned out to

be a school kept in a small temple. While the coolies were resting I sent my

card to the schoolmaster, and was promptly invited to pay a visit of

inspection. It proved to be a private school of some thirty boys and one girl,

the master's daughter. They were of all ages from six years upwards, and, I was

told, generally stayed from one to five years at school. Instruction was

limited to reading and writing, and two boys were called up to show what they

could do. To ignorant me they seemed to do very well, reading glibly down their pages of hieroglyphics.

At another stop I had a talk with the village

headman. He was elected for one year, he told me, by the people of the hamlet,

comprising about forty families. He confessed his inability to read or write,

but his face was intelligent and his bearing showed dignity and self-respect.

Petty disputes and breaches of the peace were settled by him according to

unwritten custom and his native shrewdness; and he was also responsible for the

collection of the land tax due from the village.

The people in this part of Szechuan seemed fairly

prosperous, but the prevalence of goitre was very unpleasant. The natives

account for it in various ways, the use of white salt or the drinking of

water made from melting snow.

On the 20th of April we reached Hui-li-chou. The

approach to the town or group of towns which make up this, the largest place in

southern Szechuan, was charming, through high hedges gay with pink and white

flowers. In the suburbs weaving or dyeing seemed to be going on in every house.

Sometimes whole streets were given over to the dyers, naked men at work above

huge vats filled with the inevitable blue of China. After crossing the half-dry

bed of a small river we found ourselves under the great wall of Hui-li proper.

Turning in at the South Gate we rapidly traversed the town to our night's

lodging-place near the North Gate, the crowds

becoming ever denser, people swarming out from the restaurants and side

streets, as the news spread of the arrival of a "yang-potsz" (foreign

woman). The interest was not surprising, as I was only the third or fourth

European woman to come this way, but it was my first experience alone in a

large town, and the pressing, staring crowd was rather dismaying; however, I

found comfortable companionship in the smiling face of a little lad running

beside my chair, his swift feet keeping pace with the carriers. I smiled back,

and when the heavy doors of our night's lodging-house closed behind us, I found

the small gamin was inside, too, self-installed errand boy. He proved quick

and alert beyond the common run of boys, East or West, and made himself very

useful, but save when out on errands he was always at my side, watching me with

dog-like interest, and kowtowing to the ground when I gave him a small reward.

The next morning he was on duty at dawn, and trotted beside my chair until we

were well on our way, when I sent him back. I should have been glad to have

borrowed or bought or stolen him.

Hui-li-chou, with a population of some forty

thousand, is in the middle of an important mining region, both zinc and copper

ore being found in the neighbouring hills in good quantity; but the bad roads

and government restrictions combine to keep down industry. In

spite of its being a trading centre the inns are notoriously bad, and we were

fortunate in finding rooms in a small mission chapel maintained by a handful of

native Christians. In the course of the evening some of them paid me a call.

They seemed intelligent and alert, and although in the past the town has had an

unpleasant reputation for hostility to missions, conditions at the present time

were declared to be satisfactory.

|