| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2015 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER VI TACHIENLU Tachienlu

is surely sui generis; there can be no other

town quite like it. Situated eight thousand four hundred feet above the sea, it

seems to lie at the bottom of a well, the surrounding snow-capped mountains

towering perhaps fifteen thousand feet in the air above the little town which,

small as it is, has hardly room to stand, while outside the wall there is

scarcely a foot of level ground. It is wedged into the angle where three

valleys come together, the Tar and the Chen rivers meeting just below the town

to form the Tarchendo, and our first view of the place as we turned the cliff

corner that here bars the gorge, was very striking, grey walls and curly roofs

standing out sharply from the flanking hillsides. Within the walls of Tachienlu, China and Tibet meet.

As we made our way through the long, dirty main street, here running parallel

with the Tar which comes tumbling down from the snow-fields of the Tibetan

range, I was struck at once by the varied aspect of the people. The dense crowd

that surged through the streets, some on horseback and some on foot, was more

Tibetan than Chinese, but the faces that peered out from the shops were

unmistakably of the Middle Kingdom. Groups of

fierce-looking fellows, clad in skins and felt, strode boldly along, their dark

faces bearing indelible marks of the hard, wild life of the Great Plateau. Many

of them carried weapons of some sort, for the Chinese have scorned to disarm

them. Among them walked impassively the blue-gowned men of the ruling race,

fairer, smaller, feebler, and yet undoubtedly master. It was the triumph of the

organizing mind over the brute force of the lower animal. Almost one man in

five was a red-robed lama, no cleaner in dress nor more intelligent in face

than the rest, and above the din of the crowd and the rush of the river rose

incessantly weird chanting and the long-drawn wail of horns from the temples

scattered about the town. Lamaism has Tachienlu in its grip, and I could have

fancied myself back in Himis lamassery, thousands of miles away on the western

frontier of Tibet. It was an extraordinarily picturesque scene, full of life

and sound and colour. Marco Polo described the territory lying west of

Ya-chou as "Thibeth," and a century ago the Chinese frontier stopped

at Tachienlu, but to-day Batang, a hundred and twenty-five miles to the west as

the crow flies, is the western limit of Szechuan. In actual fact, however,

direct administration by the Chinese stops at the Ta Tu, on the right bank of

the river the people being governed by their tribal chiefs. Tachienlu is in the

principality of the King of Chala, whose palace is one of the two or three

noteworthy buildings in the place, and the Tibetan population of some seven

hundred families, not counting the lamas, is directly under his authority. But

there is a power behind the throne, and the town is really governed by the

Chinese officials, for it is the key to the country to the west, and the

Imperial Government has long been awake to the importance of controlling the

great trade and military road to Lhasa. What the effect of the Revolution will

be upon the relations of China and Tibet remains to be seen. Already Chao Erh

Feng, the man who as Warden of the Marches had made Chinese rule more of a

reality in Lhasa than ever before, has fallen a victim to Manchu weakness;

hated by Chinese and Tibetan alike, he met his death at the hands of a rebellious

soldiery in January, 1912.  A VIEW OF TACHIENLU  TIBETANS Between Tachienlu and Lhasa

lie many hundred miles of barren, windswept plateaus

and perilous mountain passes. There are, I believe, at least ten of these

passes higher than Mont Blanc. Connection between the two places is over one of

the most difficult mountain roads in the world, yet it was by this route that

the Chinese finally conquered Tibet in the eighteenth century, and to-day most

of the trade goes the same way. Those who deny the Chinese all soldierly

qualities must have forgotten their achievements against the Tibetans, let

alone the still more extraordinary military feat of

their victory over the Gurkhas of Nepal, when a force of seventy thousand men

of the Middle Kingdom crossed the whole width of the most inaccessible country

in the world, and, fighting at a distance of two thousand miles from their

base, defeated the crack warriors of the East. The China Inland Mission has a station at Tachienlu,

but to my disappointment the two missionaries were away at the time of my

visit, and although their Chinese helpers made me welcome, providing a place

for me in one of the buildings of the mission compound, I felt it a real loss

not to talk with men who would have had so much of interest to tell. Moreover,

I had been looking forward to meeting my own kind once more after two weeks of

Chinese society. Fortunately another traveller turned up in Tachienlu about the

time I did, an English officer of the Indian army, returning to duty by a

roundabout route after two years' leave at home. As he too was installed in the

mission compound we soon discovered each other, and I had the pleasure of some

interesting talk, and of really dining again. Eating alone in a smelly Chinese

inn cannot by any stretch be called dining. I found that Captain Bailey had

gone with the Younghusband expedition to Lhasa, and was now on his way to

Batang with the hope of being able to cross Tibet from the Chinese side. We had

an enjoyable evening comparing experiences. I was impressed, as often before, by the comfort a man manages to secure for

himself when travelling. If absolutely necessary, he will get down to the bare

bones of living, but ordinarily the woman, if she has made up her mind to rough

it, is far more indifferent to soft lying and high living, especially the

latter, than the man. One thing I had, however, that Captain Bailey lacked, a

dog, and I think he rather envied me my four-footed companion. I know I

begrudged him his further adventure into the wilds beyond Tachienlu. Months

later I learned that although he did not reach Lhasa as he had hoped to do, his

explorations in the little-known region between Assam and Tibet and China had

won him much fame and the Gill Medal awarded by the Royal Geographical Society. Thanks to Captain Bailey I suffered no inconvenience

from the absence of the missionaries on whom I had relied for help in getting a

cheque cashed, as he kindly introduced me to the postmaster, to whom he had

brought a letter from the English post-commissioner at Chengtu, and this

official most courteously gave me all the money I needed for the next stage of

my journey. The Imperial Post-Office was in 1911 still under the same

management as the customs service, and was marked by the same efficiency. All

over China it had spread a network of post-routes, and by this time, unless the

Revolution has upset things, as it probably has, there should be a regular mail service between Tachienlu and Batang and

Lhasa. To be sure, the arrangements at Tachienlu were rather primitive, but the

surprising thing was that there should be any post-office at all. When I went

for my letters the morning after I arrived, I was shown a large heap of stuff

on the floor of the little office, and the interpreter and I spent a good

half-hour disentangling my things from the dusty pile, most of which was

apparently for members of the large French mission in Tachienlu. I was sorry

not to have a chance to meet representatives of the mission, which has been

established for a long time, and works, I believe, among both Tibetans and Chinese,

the Protestants confining themselves to the Chinese community. Nor was I more

successful in learning about the Protestant work, owing to the absence of the

missionaries on a journey to Batang. But I was greatly impressed by the truly

beautiful face and dignified bearing of a native pastor who called upon me at

my lodgings. Fine, serene, pure of countenance, he might have posed for a

Buddha or a Chinese St. John. In my limited experience of the Chinese, the men

who stand out from their fellows for beauty of expression and attractiveness of

manner are two or three Christians of the better class. Naturally fine-featured

and of dignified presence, the touch of the Christian faith seems to have

transformed the supercilious impassiveness of their class

into a serenity full of charm. It is a pity that it is not more often so, but

the zeal of the West mars as well as mends, and in imparting Western beliefs

and Western learning carelessly and needlessly destroys Eastern ideals of

conduct and manner, often more reasonable and more attractive than our own. The

complacent cocksureness of the Occidental attitude toward Oriental ways and

standards has little to rest on. We have reviled the people of the East in the

past for their unwillingness to admit that there was anything we could teach

them, and they are amending their ways, but we have shown and show still a

stupidity quite equal to theirs in our refusal to learn of them. Take, for

example, the small matter of manners, if it be a small matter. More than one teacher

in America has confessed the value of the object lesson in good breeding given

by the chance student from the East, but how few Westerners in China show any

desire to pattern after the dignified, courteous bearing of the Chinese

gentleman. I have met bad manners in the Flowery Kingdom, but not among the

natives. It had been a long, hard pull from Ning-yόan-fu; two

weeks' continuous travelling is a tax upon every one, but at no place had we

found comfortable quarters for the whole of the party, and as the men preferred

to push on, I was not inclined to object. But usually a seventh-day rest is

very acceptable to them; so we were all glad for a

little breathing-space in Tachienlu. The servants and coolies spent the first

day in a general tidying-up, getting a shave, face and head, and having their

queues washed and combed and replaited. Some also made themselves fine in new

clothes, but others were content to wash the old. As none of them, with the

exception of the fu t'ou, had ever been in Tachienlu before, they were as keen

to see the sights as I was, and in my rambles about the town the next two or

three days, I was greeted at every turn by my coolies, enjoying to the full

their hard-earned holiday. There was less to see of interest in Tachienlu than I

had expected. The shops are filled mainly with ordinary Chinese wares, and my

efforts to find some Tibetan curios were fruitless, those shown to me being of

little value. I imagine it is a matter of chance if one secures anything really

worth while. At any rate, neither the quaint teapots nor the hand

praying-wheels that I was seeking were forthcoming. Nor could I find any decent

leopard skins, which a short time ago formed an important article of commerce,

so plentiful were they. But at least I had the fun of bartering with the

people, whom I found much the most interesting thing in Tachienlu, and thanks

to the indifference or the politeness of the Tibetan I was able to wander about

freely without being dogged by a throng of men and boys. Chinese soldiers were much in evidence, for this is naturally an important

military post as well as the forwarding depot for the troops stationed along

the great western trade route to Batang and Lhasa. The Chinese population under

their protection, numbering some four hundred families, mostly traders, looked

sleek and prosperous. Evidently they made a good living off the country, unlike

the Tibetans who were generally dirty and ragged and poor in appearance. I must

confess that I was disappointed at the latter. In spite of their hardy,

muscular aspect and bold bearing, I did not find them attractive as do most

travellers. They lacked the grotesque jollity of the Ladakhis of Western Tibet,

their cousins in creed and race, and I met nothing of the manly friendliness

which marked the people of Mongolia whom I had to do with later. Never have I

seen men of more vicious expression than some I met in my strolls about

Tachienlu, and I could well believe the stories told of the ferocity shown by

the lamas along the frontier. Very likely the people are better than their

priests, but if so, their looks belie them. There is rarely a man or a people

so low as to lack a defender, and it is a pleasing side to the white man's

rule in the East, that if he be half a man he is likely to stand up for the

weak folk he governs. It may be due to pride of ownership, or it may be the

result of a knowledge born of intimate acquaintance, but whatever the cause, no

race is quite without champions in the white man's

congress. Captain Bailey who had had long experience of the Tibetans in

administrative work on the northeastern borderland of India, was no exception,

and he defended them vigorously. I had no knowledge to set against his, but

when he declared that they were a clean people it seemed to me he was

stretching a point, for I should have thought their dirt was as undeniable as

it was excusable in the burning sun or biting cold of their high plateaus. Practically all the traffic between China and its

great western dependency passes through Tachienlu, and the little town is full

of bustle and stir. From Tibet are brought skins and wool and gold and musk, to

be exchanged here for tobacco and cloth and miscellaneous articles, but tea, of

course, forms the great article of trade, the quantity sent from Tachienlu

annually amounting to more than twelve million pounds. Conspicuous in the town

are the great warehouses where the tea is stored, awaiting sale, and there are

numerous Tibetan establishments where it is repacked for the animal carriage

which here replaces the carrier coolies from the east. Among the Chinese the

trade is mostly in the hands of a few great merchants who deal with the women

representatives of the Tibetan priesthood who practically monopolize the sale

in their country, deriving a large income from the high prices they charge the

poor people to whom tea is a necessity of life. When I grew weary of the confusion and dirt of the

narrow streets I was glad to escape to the hillside above my lodgings. The

mission compound is small and confined, affording no room for a garden,

although fine masses of iris growing along the walls brightened up the severity

of the grey stone buildings; but a little climb behind the mission house

brought me to a peaceful nook whence I could get a glorious view over the town

and up and down the valley, here so narrow that it seemed possible to throw a

stone against the opposite hillside. The first fine morning after my arrival I made an

early start for the summer palace of the King of Chala, situated about eight miles

from Tachienlu in a beautiful, lonely valley among the mountains. This is the

favourite camping-place of Chengtu missionaries, who now and then brave the

eleven days' journey to and fro to exchange their hothouse climate for a brief

holiday in the glorious scenery and fine air of these health-giving uplands. We

were mounted, the interpreter and I, on ponies provided by the Yamen, one worse

than the other, and both unfit for the rough scramble. After traversing the

town, first on one side and then on the other of the river which we crossed by

a picturesque wooden bridge, roofed in but with open sides, we passed out at

the South Gate Tachienlu has no West Gate and found ourselves in a small suburb with a few meagre gardens. A mile farther

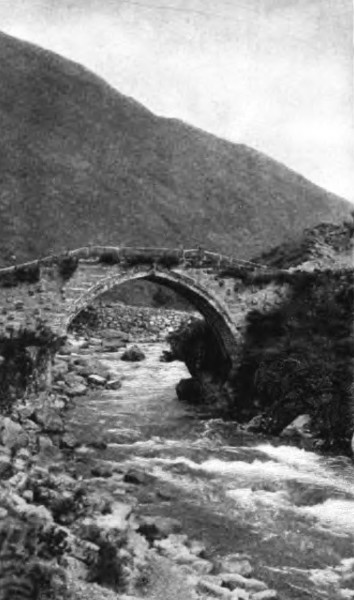

along we crossed the river again by a striking single arch bridge, known as the

"Gate of Tibet." We were now on the great trade route to Lhasa, but

between us and the mysterious city lay many days of weary travel. From time to time we met groups of Tibetans, men and

women, rough-looking and shy, with the shyness of a wild animal. Generally

after a moment's pause to reassure themselves, they answered my greeting in

jolly fashion, seeming quite ready to make friends. Occasionally the way was

blocked by trains of ox-like yaks, the burden-bearers of the snow-fields,

bringing their loads of skins and felt and musk and gold. Astride of one was a

nice old man who stuck out his tongue at me in polite Tibetan fashion.  LAMA AND DOG AT TACHIENLU  THE GATE OF TIBET After an hour's ride we left

the highway and turned into a beautiful green valley, following a very bad

trail deeper and deeper into the mountains, the soft meadows gay with flowers

forming a charming contrast to the snow-peaks that barred the upper end of the

valley. We came first to the New Palace, a large rambling building having no

more architectural pretensions than an ordinary Chinese inn. As the king's

brother, who makes his home there, was away, I saw nothing more of the place

than the great courtyard filled with mangy, half-starved dogs and unkempt men. Not far off is one of the great attractions of the

place, at least to the natives, a hot sulphur spring. To the disappointment

of my Tibetan guide I declined to visit it, preferring a leisurely cold lunch

on the bank of a rushing stream which was vigorously turning a large

prayer-wheel, a cylinder of wood inscribed many times over with the mystic

words of the Buddhist prayer, "Om mani padme hum," oftenest repeated

perhaps of all prayers. Each revolution of the wheel was equivalent to as many

repetitions of the words as there were inscribed on the wood. So night and day,

while the stream runs, prayers are going up for the king, and truly he needs

them, poor man, between the bullying of his Chinese overlords and the

machinations of turbulent lamas. Other indications of the Buddhist's

comfortable way of getting his prayers said for him are found all about

Tachienlu. From temple roof and wayside rock flags bearing the same legend wave

in the breeze, each flutter a prayer, and just outside the city we rode by a long

stone wall, much like those of New England, only its top was covered over with

inscribed stones. If you passed by, having the "mani" wall on your

right hand, each inscribed stone would pray for you; hence the trail always

forks to suit the coming and the going Buddhist, and I remember well the

insolent pride with which my Mohammedan servants always took the right hand when passing these walls in Ladakh. A mile farther up the valley we came to the Old

Palace, a collection of hovels banked with piles of manure. Far more attractive

than the royal residence were some tents not far off, where a band of Tibetans,

retainers of the prince, were encamped. They came out to greet us in friendly

fashion, pointing out a blind trail up the valley where we could get better

views of the snow-peaks; but we had to turn back, sorry though I was to leave

the spot, parklike in its beauty of forest and meadow, a veritable oasis in a

wilderness of rock and ice. It was more like home than anything I had seen in

West China, for there were stretches of fine, grassy meadows where the royal

herds of cattle were grazing, and all at once I realized that it was weeks

since I had seen a field of grass or real cows. It is the great lack in this

country. Pigs abound, and fowls, but there is no place for cattle, and the

horses live on beans and corn, or more likely on leaves and twigs. Priest-ridden Tachienlu boasts many temples and

lamasseries, and the last day of my stay I paid a visit to one of the largest,

not far from the South Gate. It was a wide, rambling, wooden building standing

near a grove of unusually fine trees, a sort of alder. The approach was not

unattractive, flowers growing under the walls and about the entrance. Once

inside the portal, we found ourselves in a large courtyard paved

with stone and surrounded by two-story galleried buildings. Facing us was the

temple, scarcely more imposing in outward appearance than the others. On one

side a group of half-naked lamas were gathered about an older man who seemed to

be relating or expounding something, whether gossip or doctrine I could not

tell, but I should judge the former from their expressions. They paid little

attention to us, nor did others strolling about the yard, but the big dogs

roaming loose were not backward in their greeting, although to my surprise they

did not seem at all ferocious, and treated my imperturbable little dog with

distant respect. Earlier travellers recount unpleasant experiences, but perhaps

the lamas have learned better in late years, and fasten up their dangerous dogs

if visitors are expected. Afterwards I saw in another inner courtyard a large,

heavy-browed brute adorned with a bright red frill and securely chained. He

looked savage, and could have given a good account of himself in any fight. While I was waiting for permission to enter the

temple, I inspected the stuffed animals dogs, calves, leopards suspended on

the verandah. They were fast going to decay from dust and moth, but I was told

that they were reputed sacred. The temple, which we were forced to enter from a

side door, was large and high, hung with scrolls and banners and filled with

images, but it was so dark that I found it difficult

to discern much save a good-sized figure of Buddha, not badly done. At the invitation of an old lama, a friend of our

guide, I was invited to a large, disorderly dining- or living-hall on the upper

floor, where we were very courteously served with tea, Chinese fashion. The old

man had a rather nice face, and I tried to learn a little about the place, but

conversation through two Chinese intermediaries, one speaking imperfect English

and the other bad Tibetan, was not very satisfactory, and I soon gave up the

attempt. I did succeed, however, in making the lama understand my wish to hire

some one to cut for me a praying-stone, to which he replied that there were

plenty outside, why did I not take one of them? I had thought of that myself,

but feared to raise a storm about my ears. Now, acting on his advice, I made a

choice at my leisure and no one objected. Under the double restraint of an

unusually strong prince, backed by Chinese officials, the priests of Tachienlu

are less truculent than farther west, but at best Lamaism rests with a heavy

hand upon the Tibetans; it is greedy and repulsive in aspect and brutalizing in

its effects; wholly unlike the gentle, even though ignorant and superstitious,

Buddhism of China. |