| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2015 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER XIII ACROSS THE DESERT OF GOBI Toward

the end of the third day from Kalgan we were

following a blind trail among low, grass-covered hills, all about us beautiful

pastureland dotted over with herds of horses and cattle. A sharp turn in the

road revealed a group of yurts like many that we had passed, but two khaki

tents a little at one side showed the European, and in a few minutes I found

myself among the new friends that so speedily become old friends in the corners

of the world. Here I was to make the real start for my journey

across the desert, and by good luck it turned out that one member of the little

settlement, a man wise in ways Mongolian, was leaving the next morning for a

trip into the heart of Mongolia, and if I went on at once we could journey

together for the two or three days that our ways coincided. There was nothing

to detain me, fortunately, and by noon the next day I was again on the road. I looked with some complacency at my compact but

wholly adequate little caravan. My luggage, including a capacious Chinese

cotton tent, was scientifically stowed away in a small Russian baggage cart, a strong, rough, two-wheeled affair drawn by two

ponies, and driven by the Mongol who was to guide me to Urga. My boy bestrode

rather gingerly a strong, wiry little Mongol pony, of the "buckskin"

sort, gay with Western saddle and red cloth. Wang bravely said he would do his

best to ride the pony when I did not care to use him, but he added pathetically

that he had never before mounted anything save a donkey. As for me, I sat

proudly in an American buggy, a "truly" one, brought from the United

States to Tientsin and then overland to Kalgan. It was destined for a Mongol

prince in Urga, and I was given the honour of taking it across the desert.

There are various ways of crossing Mongolia, in the saddle, by pony, or camel

cart; one and all are tiring; the desert takes its toll of the body and the spirit.

But here was a new way, and if comfort in Gobi is obtainable it is in an

American buggy; and with a pony for change, no wonder I faced the desert

without dismay. The combined caravans looked very imposing as we

moved off. All told, we were one Swede, one American, one Chinese, seven

Mongols, one Irishman (Jack), and twelve horses. Three of the Mongols were

lamas, the rest were laymen, or "black men," so called from their

unshorn black hair worn in a queue. They were all dressed much alike, although

one of the lamas had clothes of the proper red

colour, and all rode their sturdy ponies well, mounted on high-peaked saddles. After the first day we fell into our regular course,

an early start at six o'clock or so, long halt at noon, when tents were set up,

and all rested while the horses grazed, and then on again until the sun went

down below the horizon. During the hotter hours I took my ease in the buggy,

but in the early morning, and at the end of the day I rode. The Mongols were

gay young fellows, taking a kindly interest in my doings. One, the wag of the

party, was bent on learning to count in English, and each time he came by me he

chanted his lesson over, adding number after number until he reached twenty.

The last few miles before getting into camp was the time for a good race. Then,

riding up with thumbs held high in greeting, they would cry to me

"San?" ("All right?") and answering back "San!" I

touch my horse and we are off. Oh, the joy of those gallops with the horsemen

of the desert! For the moment you are mad. Your nomad ancestors we all have

them awake in you, and it is touch and go but you turn your back forever on

duties and dining, on all the bonds and frills that we have entangled ourselves

in and then you remember, and go sadly to bed. The weather was delightful; whatever there might be

in store for me, the present was perfect. A glorious dawn, no severe heat but

for a short time in the middle of the day, which cooled off rapidly in the late

afternoon, the short twilight ending in cold, starlit nights. The wonder of

those Mongolian nights! My tent was always pitched a little apart from the

confusion of the camp, and lying wrapped in rugs in my narrow camp-bed before

the doors open to the night wind, I fell asleep in the silence of the limitless

space of the desert, and woke only as the stars were fading in the sky.  JACK AND HIS LAMA FRIEND  MY CARAVAN ACROSS MONGOLIA At first we were still in the grassland; the rolling country was covered with a thick mat of grass dotted with

bright flowers, and yurts and men and herds abounded. Happenings along the road

were few. The dogs always rushed out from the yurts to greet us. They looked

big and savage, and at first, mindful of warnings, I kept close guard over

Jack; but he heeded them as little as he had the Chinese curs, and hardly deigned

a glance as he trotted gaily along by the horses who had captured his Irish

heart. Once we stopped to buy a pony, and secured a fine "calico"

one, unusually large and strong. Again a chance offered to get a sheep, not

always possible even though thousands are grazing on the prairie, for a Mongol

will sell only when he has some immediate use for money. The trade once made,

it took only a short time to do the rest, to kill, to cut up, to boil in a

big pot brought for the purpose, to eat. Two hundred miles from Kalgan we passed the telegraph station of Pongkiong manned by two Chinese. It

is nothing but a little wooden building with a bit of a garden. The Chinese has

his garden as surely as the Englishman, only he spends his energy in growing

things to eat. At long intervals, two hundred miles, these stations are found

all the way to Urga and always in the charge of Chinese, serviceable, alien,

homesick. It must be a dreary life set down in the desert without neighbours or

visitors save the roving Mongol whom the Chinese look down on with lofty

contempt. Indeed, they have no use for him save as a bird to be plucked, and

plucked the poor nomad is, even to his last feather. It is not the Chinese

Government but the Chinese people that oppress the Mongol, making him ready to

seek relief anywhere. Playing upon his two great weaknesses, lack of thrift and

love of drink, the wandering trader plies the Mongol with whiskey, and then,

taking advantage of his befuddled wits, gets him to take a lot of useless

things at cut-throat prices but no bother about paying, that can be settled

any time. Only when pay-day comes the debts, grown like a rolling snowball,

must be met, and so horses and cattle, the few pitiful heirlooms, are swallowed

up, and the Mongol finds himself afoot and out of doors, another enemy of

Chinese rule. Whenever we halted near yurts, the women turned out

to see me, invading my tent, handling my things. They

seemed to hold silk in high esteem. My silk blouses were much admired, and when

they investigated far enough to discover that I wore silk "knickers,"

their wonder knew no bounds. In turn they were always keen to show their

treasures, especially of course their headdresses, which were sometimes very

beautiful, costing fifty, one hundred, or two hundred taels. A wife comes high in Mongolia, and divorce must be

paid for. A man's parents buy him a wife, paying for her a good sum of money

which is spent in purchasing her headgear. If a husband is dissatisfied with

his bargain he may send his wife home, but she takes her dowry with her. I am

told the woman's lot is very hard, and that I can readily believe: it generally

is among poor and backward peoples; but she did not appear to me the

downtrodden slave she is often described. On the contrary, she appeared as much

a man as her husband, smoking, riding astride, managing the camel trains with a

dexterity equal to his. Her household cares cannot be very burdensome, no

garden to tend, no housecleaning, simple cooking and sewing; but by contrast

with the man she is hard-working. Vanity is nowise extinct in the feminine

Mongol, and, let all commercial travellers take note, I was frequently asked

for soap, and nothing seemed to give so much pleasure as when I doled out a

small piece. Perhaps in time even the Mongol will

look clean. Asiatics as a rule know little about soap; they clean their clothes

by pounding, and themselves by rubbing; but sometimes they put an exaggerated

value upon it. A Kashmir woman, seeing herself in a mirror side by side with

the fair face of an English friend of mine, sighed, "If I had such good

soap as yours I too would be white." But there is a good deal to be said against washing,

at least one's face, when crossing Gobi. The dry, scorching winds burn and

blister the skin, and washing makes things worse, and besides you are sometimes

short of water; so for a fortnight my face was washed by the rains of heaven

(if at all), and my hair certainly looked as though it were combed by the wind,

for between the rough riding and the stiff breezes that sweep over the plateau,

it was impossible to keep tidy. But, thanks to Wang, I could always maintain a

certain air of respectability in putting on each morning freshly polished

shoes. Of wild life I saw little; occasionally we passed a

few antelope, and twice we spied wolves not far off. These Mongolian wolves are

big and savage, often attacking the herds, and one alone will pull down a good

horse or steer. The people wage more or less unsuccessful war upon them and at

times they organize a sort of battue. Men, armed with lassoes, are stationed at

strategic points, while others, routing the wolves from their lair, drive them

within reach. Sand grouse were plentiful, half

running, half flying before us as we advanced, and when we were well in the

desert we saw eagles in large numbers, and farther north the marmots abounded,

in appearance and ways much like prairie dogs. At first there were herds on every side. I was struck

by the number of white and grey ponies, and was told that horses are bred

chiefly for the market in China, and this is the Chinese preference. Cattle and

sheep are numbered by thousands, but I believe these fine pasture lands could

maintain many more. Occasionally we saw camels turned loose for the summer

grazing; they are all of the two-humped Bactrian sort, and can endure the most

intense winter cold, but the heat of the summer tells upon them severely, and

when used in the hot season, it is generally only at night. From time to time we passed long baggage trains, a

hundred or more two-wheeled carts, each drawn by a bullock attached to the tail

of the wagon in front. They move at snail's pace, perhaps two miles an hour,

and take maybe eight weeks to make the trip across the desert. Once we met the

Russian parcels-post, a huge heavily laden cart drawn by a camel and guarded by

Cossacks mounted on camels, their uniforms and smart white visored caps looking

very comical on the top of their shambling steeds. Most of the caravans were in

charge of Chinese, and they thronged about us if a

chance offered to inspect the strange trap; especially the light spider wheels

aroused their interest. They tried to lift them, measured the rim with thumb

and finger, investigated the springs, their alert curiosity showing an

intelligence that I missed in the Mongols, to whom we were just a sort of

travelling circus, honours being easy between the buggy, and Jack and me. We were now in the Gobi. The rich green of the

grassland had given way to a sparse vegetation of scrub and tufts of coarse

grass and weeds, and the poor horses were hard put to get enough, even though

they grazed all night. The country, which was more broken and seamed with

gullies and rivers of sand, Sha Ho, had taken on a hard, sunbaked, repellent

look, brightened only by splendid crimson and blue thistles. The wells were

farther apart, and sometimes they were dry, and there were anxious hours when

we were not sure of water for ourselves, still less for the horses. One well

near a salt lake was rather brackish. This lake is a landmark in the entire

region round; it seems to be slowly shrinking, and many caravans camp here to

collect the salt, which is taken south. The weather, too, had changed; the days

were hotter and dryer, but the nights were cool and refreshing always. For eleven days we saw no houses but the two

telegraph stations, save once early in the morning when

we came without warning upon a lamassery that seemed to start up out of the

ground; the open desert hides as well as reveals. It was a group of

flat-roofed, whitewashed buildings, one larger than the rest, all wrapped in

silence. There was no sign of life as we passed except a red lama who made a

bright spot against the white wall, and a camel tethered in a corner, and it

looked very solitary and desolate, set down in the middle of the great, empty,

dun-coloured plain. I had now separated from my travelling companions,

cheering the friendly Mongols with some of my bountiful supply of cigarettes.

As they rode off they gave me the Mongol greeting, "Peace go with

you." I should have been glad to have kept on the red lama to Urga, for he

had been very helpful in looking after my wants, and had befriended poor Jack,

who was quite done up for a while by the hot desert sands; but I let him go

well pleased with a little bottle of boracic acid solution for his sore eyes.

The Mongols, like so many Eastern peoples, suffer much from inflammation of the

eyes, the result of dirt, and even more of the acrid argol smoke filling the

yurts so that often I was compelled to take flight. I expect the stern old

Jesuit would say of them as he did of the Red Indian, "They pass their

lives in smoke, eternity in flames." For about eight days we were crossing the desert, one day much like another. Sometimes the track was all up

and down: we topped a swell of ground only to see before us another exactly

like it. Then for many miles together the land was as flat and as smooth as a

billiard table, no rocks, no roll; and we chased a never-ending line of

telegraph poles over a never-ending waste of sand. Another day we were

traversing from dawn till sundown an evil-looking land strewn with boulders and

ribs of rock, bleak, desolate, forbidding. Nowhere were there signs of life, nothing growing,

nothing moving. For days together we saw no yurts, and more than one day passed

without our meeting any one. Once there appeared suddenly on the white track

before us a solitary figure, looking very pitiful in the great plain. When it

came near it fell on its face in the sand at our feet, begging for food. It was

a Chinese returning home from Urga, walking all the seven hundred miles across

the desert to Kalgan. We helped him as best we could, but he was not the only

one. An old red lama, mounted on a camel and bound for

Urga, kept near us for two or three days, sleeping at night with my men by the

cart, and sometimes taking shelter under my tent at noon, where he sat quietly

by the hour smoking my cigarettes. He was a nice old fellow with pleasant ways,

nearly choking himself in efforts to make me understand how wonderful I was, travelling all alone, and what splendid sights I

should behold in Urga. And so time passed; tiring, monotonous days,

refreshing, glorious nights, and then toward the end of a long, weary afternoon

I saw for a moment, faintly outlined in the blank northern horizon, a cloud? a

mountain? a rock? I hardly dared trust my eyes, and I looked again and again.

Yes, it was a mountain, a mountain of rocks just as I was told it would loom up

in front of me for a moment, and then disappear; and it disappeared, and I rejoiced,

for at its base the desert ended; beyond lay a land of grass and streams. We camped that evening just off the trail in a little

grassy hollow. In the night rain fell, tapping gently on my tent wall, and for

hours there mingled with the sound of the falling rain the dull clang of bells,

as a long bullock train crawled along in the dark on its way to Urga. The next day rose cloudless as before. My landmark

could no longer be seen, but I knew it was not far off, "a great rock in a

weary land," and already the air was fresher and the country seemed to

have put on a tinge of green. In the afternoon a little cavalcade of wild,

picturesque-looking men dashed down upon us in true Mongol style, trailing the

lasso poles as they galloped. With a gay greeting they turned their horses

about, and kept pace with us while they satisfied their curiosity. This was my first sight of the northern Mongol, who

differs little from his brother of the south, save that he is less touched by

Chinese influence. In dress he is more picturesque, and the tall, peaked hat

generally worn recalled old-time pictures of the invading Mongol hordes. The great mountain had again come in sight, crouching

like a huge beast of prey along the boulder-strewn plain. But where was the

famous lamassery that lay at its foot? Threading our way through a wilderness

of rock, heaped up in sharp confusion, we came out on a little ridge, and there

before us lay Tuerin, not a house but a village, built in and out among the

rocks. It was an extraordinary sight to stumble upon, here on the edge of the

uninhabited desert. A little apart from the rest were four large temples

crowned with gilt balls and fluttering banners, and leading off from them were

neat rows of small white plastered cottages with red timbers, the homes of the

two thousand lamas who live here. The whole thing had the look of a seaside

camp-meeting resort. A few herds of ponies were grazing near by, but there was

no tilled land, and these hundreds of lamas are supported in idleness by contributions

extorted from the priest-ridden people. A group of them, rather

repulsive-looking men, came out to meet us, or else to keep us off. As it was

growing late, and we had not yet reached our camping-place, I did not linger

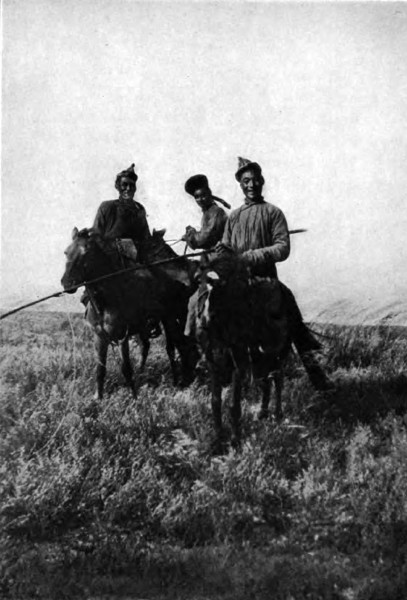

long.  HORSEMEN OF THE DESERT, NORTH MONGOLIA We camped that night in the shadow of the mountain. The ground was carpeted with artemisia, which when

crushed gave out a pungent odour almost overpowering. Before turning in we

received a visit from a Chinese trader who gave us a friendly warning to look

out for horse-thieves; he had lost a pony two nights back. Here, then, were the

brigands at last! For the next three nights we kept sharp watch, camping far

off the road and bringing the ponies in around my tent before we went to sleep.

One night, indeed, the two men took turns in sitting up. Fortunately my Chinese

boy and the Mongol hit it off well, for the Mongol will not stand bullying, and

the Chinese is inclined to lord it over the natives. But Wang was a good soul,

anxious to save me bother, and ready to turn his hand to anything, putting up

tents, saddling ponies, collecting fuel, willing always to follow the Mongol's

lead save only in the matter of getting up in the morning. Then it was Wang

who got us started each day, lighting the fire before he fell upon Tchagan Hou

and pulled him out of his sheepskin; but once up, the Mongol took quiet and

efficient control. At Tuerin country and weather changed. There was now

abundance of grass, and the ponies could make up for the lean days past.

Thousands of cattle and sheep again gladdened our eyes, and the pony herds were a splendid sight; hundreds of beautiful

creatures, mostly chestnut or black, were grazing near the trail or galloping

free with flowing mane and tail. We had been warned that the rainy season was setting

in early, and for three days we met storm after storm, delaying us for hours,

sometimes keeping us in camp a day or more. We stopped for tiffin the first day

just in time to escape a drenching, and did not get away again until six

o'clock. As some Chinese pony traders had encamped alongside of us, and there

were two or three yurts not far away, I did not lack amusement. The Mongolian

women camped down in my tent as soon as it was up, making themselves much at

home. One was young and rather good-looking, and all wore the striking

headdress of North Mongolia. Like that of the south, it was of silver, set with

bright stones, but it was even more elaborate in design, and the arrangement of

the hair was most extraordinary. Parted from brow to nape of the neck, the two

portions were arranged in large plastered structures like ears on either side

of the head; these extended out almost to the width of the shoulder, and were

kept in place by bars of wood or silver, the two ends of hair being braided and

brought forward over the breast. This is the style of head-dressing adopted at

marriage and rarely meddled with afterwards. The dress, too, of these northern Mongol women was striking. Over their usual loose,

unbelted garment (the Mongol for "woman" means "unbelted

one") they wore short coats of blue cotton with red sleeves, and the tops

of these were so raised and stiffened that they almost raked the wearer's ears.

On their feet they had high leather boots just like their husbands', and if

they wore a hat it was of the same tall, peaked sort. The sight of a Mongol

woman astride a galloping pony was not a thing to be forgotten; ears of hair

flapping, high hat insecurely poised on top, silver ornaments and white teeth

flashing. It was nine o'clock before we camped that night, but

we did not get off the next day until afternoon because of the rain, and again

it was nine in the evening when we pitched our tent in a charming little dell

beautiful with great thistles, blue with the blue of heaven in the lantern

light. The next day I was getting a little desperate, and

against Tchagan Hou's advice I decided to try bullying the weather, and when

the rain came on again I refused to stop. As a result we were all soaked

through, and after getting nearly bogged, all hands of us in a quagmire, I gave

it up and we camped on the drenched ground, and there we stayed till the middle

of the next day spending most of our time trying to get dry. The argols were

too wet to burn, but we made a little blaze with the wood of my soda-water box. For two days we had tried in vain to buy a sheep,

and the men's provisions were running short. If it had not been for the

generous gift of the Kalgan Foreign Office, we should have fared badly, but

Mongols and Chinese alike seemed to be free from inconvenient prejudices, and

my men, whom I called in to share the tent with me, feasted off tins of corned

beef, bologna sausage, and smoked herring, washed down by bowls of Pacific

Coast canned peaches and plums; and then they smoked; that comfort was always

theirs, and if the fire burned at all, it smoked, too, and occasionally a

drenched traveller stopped in to be cheered with a handful of cigarettes. And

then all curled up in their sheepskins and slept away long hours, and I also

slept on my little camp-bed, and outside the rain fell steadily. But at last a morning broke clear and brilliant; the

rain was really over. The ponies looked full and fit after the good rest, and

if all went well we should be in Urga before nightfall. We were off at sunrise,

and soon we entered a beautiful valley flanked on either hand by respectable

hills, their upper slopes clothed with real forests of pine. These were the

first trees I had seen, except three dwarfed elms in Gobi, since I left behind

the poplars and willows of China. Yurts, herds, men were everywhere. Two

Chinese that we met on the road stopped to warn us that the river that flowed below

Urga was very high and rising fast, hundreds of

carts were waiting until the water went down, and they doubted if we could get

across. This was not encouraging, but we pushed on. It was plain that we were

nearing the capital, for the scene grew more and more lively. At first I

thought it must be a holiday; but, no, it was just the ordinary day's work, but

all so picturesque, so full of ιlan and colour, that it was more like a

play than real life. Now a drove of beautiful horses dashed across the

road, the herdsmen in full cry after them. Then we passed a train of camels,

guided by two women mounted on little ponies. They had tied their babies to the

camels' packs, and seemed to have no difficulty in managing their wayward

beasts. Here a flock of sheep grazed peacefully in the deep green meadows

beside the trail, undisturbed by a group of Mongols galloping townwards, lasso

poles in hand, as though charging. Two women in the charge of a yellow lama

trotted sedately along, their quaint headdresses flapping as they rode. Then we

overtook three camels led by one man on a pony and prodded along by another,

actually cantering, I felt I must hasten, too, but unhurried, undisturbed,

scarcely making room for an official and his gay retinue galloping towards the

capital, a bullock caravan from Kalgan in charge of half a dozen blue-coated

Celestials moved sedately along, slow, persistent, sure

to gain the goal in good time, that was China all over. And then the valley opened into a wide plain seamed

by many rivers, and there before us, on the high right bank of the Tola and

facing Bogda Ola, the Holy Mountain, lay Urga the Sacred, second to Lhasa only

in the Buddhist world. But we were not there yet; between us and our goal

flowed the rivers that criss-cross the valley, and the long lines of carts and

horses and camels and bullocks crowded on the banks bore out the tale of the

Chinese. We push on to the first ford; the river, brimming full, whirls along

at a great rate, but a few carts are venturing in, and we venture too. Tchagan

leads the way, I follow in the buggy, while the boy on the pony brings up the

rear, Jack swimming joyously close by. The first time is great fun, and so is

the second, but the third is rather serious, for the river gets deeper and the current

swifter each time. The water is now almost up to the floor of the buggy, and

the horse can hardly keep his footing. I try to hold him to the ford, cheering

him on at the top of my voice, but the current carries us far down before we

can make the opposite bank. Four times we crossed, and then we reached a ford

that seemed unfordable. Crowds are waiting, but no one crosses. Now and then

some one tries it, only to turn back, and an overturned cart and a drowned horse show the danger. But we decide to risk it, hiring

two Mongols, a lama and a "black man," to guide our horses. One, on

his own mount, takes the big cart horse by the head; the other, riding my pony,

leads the buggy horse. Wang comes in with me and holds Jack. The crowds watch

eagerly as we start out; the water splashes our feet. First one horse, then

another, floundering badly, almost goes down, the buggy whirls round and comes

within an ace of upsetting, the little dog's excited yaps sound above the

uproar. Then one mighty lurch and we are up the bank. Four times more we repeat

the performance, and at last we find ourselves with only a strip of meadow

between us and Mai-ma-chin, the Chinese settlement where we plan to put up.

Clattering along the stockaded lane we stop before great wooden gates that open

to Tchagan's call, and we are invited in by the Mongol trader who, warned of

our coming, stands ready to bid us welcome. |