|

WHITE

HOUSE COOK BOOK.

*

* *

CARVING.

CARVING is one

important acquisition in the routine of daily living, and all should

try to

attain a knowledge or ability to do it well, and withal gracefully.

When carving use

a chair slightly higher than the ordinary size, as it gives a better

purchase

on the meat, and appears more graceful than when standing, as is often

quite

necessary when carving a turkey, or a very large joint. More depends on

skill

than strength. The platter should be placed opposite, and sufficiently

near to

give perfect command of the article to be carved, the knife of medium

size,

sharp with a keen edge. Commence by cutting the slices thin, laying

them

carefully to one side of the platter, then afterwards placing the

desired

amount on each guest's plate, to be served in turn by the servant.

In carving fish,

care should be taken to help it in perfect flakes; for if these are

broken the

beauty of the fish is lost. The carver should acquaint himself with the

choicest parts and morsels; and to give each guest an equal share of

those

tidbits should be his maxim. Steel knives and forks should on no

account be

used in helping fish, as these are liable to impart a very disagreeable

flavor.

A fish-trowel of silver or plated silver is the proper article to use.

Gravies should

be sent to the table very hot, and in helping one to gravy or melted

butter,

place it on a vacant side of the plate, not pour it over their meat,

fish or

fowl, that they may use only as much as they like.

When serving

fowls, or meats, accompanied with stuffing, the guests should be asked

if they

would have a portion, as it is not every one to whom the flavor of

stuffing is

agreeable; in filling their plates, avoid heaping one thing upon

another, as it

makes a bad appearance.

A word about the

care of carving knives: a fine steel knife should not come in contact

with

intense heat, because it destroys its temper, and therefore impairs its

cutting

qualities. Table carving knives should not be used in the kitchen,

either

around the stove, or for cutting bread, meats, vegetables, etc.; a fine

whetstone should be kept for sharpening, and the knife cleaned

carefully to

avoid dulling its edge, all of which is quite essential to successful

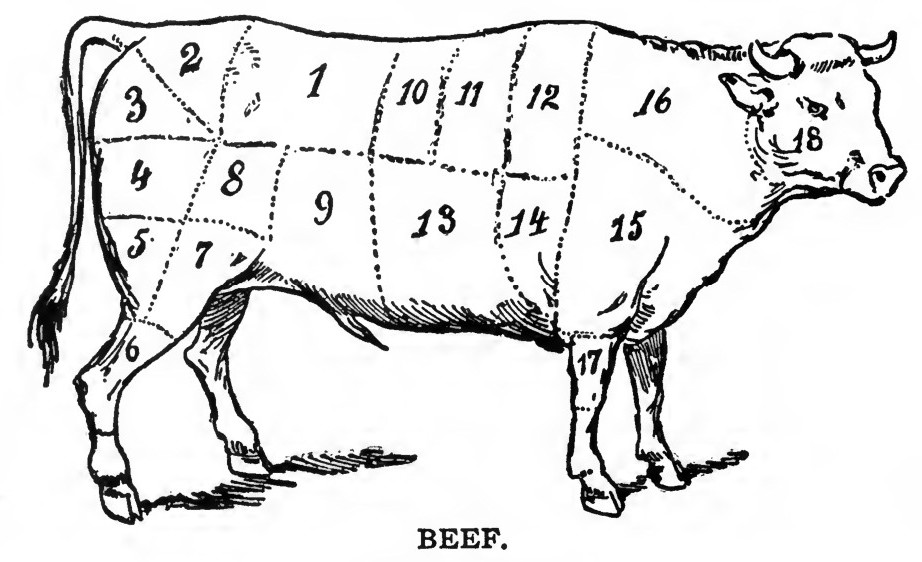

carving. BEEF

HIND-QUARTER.

No.

1. Used for choice roasts, the porter-house and sirloin steaks.

No.

2. Rump, used for steaks, stews and corned beef.

No.

3. Aitch-bone, used for boiling-pieces, stews and pot roasts.

No.

4. Buttock or round, used for steaks, pot roasts, beef à la

mode; also a

prime boiling-piece.

No.

5. Mouse-round, used for boiling and stewing.

No.

6. Shin or leg, used for soups, hashes, etc.

No.

7. Thick flank, cut with under fat, is a prime boiling-piece, good for

stews

and corned beef, pressed beef.

No.

8. Veiny piece, used for corned beef, dried beef.

No.

9. Thin flank, used for corned beef and boiling-pieces.

FORE-QUARTER.

No.

10. Five ribs called the fore-rib. This is considered the primest piece

for

roasting; also makes the finest steaks.

No.

11. Four ribs, called the middle ribs, used for roasting.

No.

12. Chuck ribs, used for second quality of roasts and steaks.

No.

13. Brisket, used for corned beef, stews, soups and spiced beef.

No.

14. Shoulder-piece, used for stews, soups, pot-roasts, mince-meat and

hashes.

Nos.

15, 16. Neck, clod or sticking-piece used for stocks, gravies, soups,

mince-pie

meat, hashes, bologna sausages, etc.

No.

17. Shin or shank, used mostly for soups and stewing.

No.

18. Cheek.

The following is

a classification of the qualities of meat, according to the several

joints of

beef, when cut up.

First Class. — Includes the sirloin with

the kidney suet (1), the rump steak piece (2), the fore-rib (11).

Second Class. — The buttock or round (4)

, the thick flank (7), the middle ribs (11).

Third Class. — The aitch-bone (3), the

mouse-round (5), the thin flank (8, 9), the chuck (12), the

shoulder-piece

(14), the brisket (13).

Fourth Class. — The clod, neck and

sticking-piece (15, 16).

Fifth Class. — Shin or shank (17).

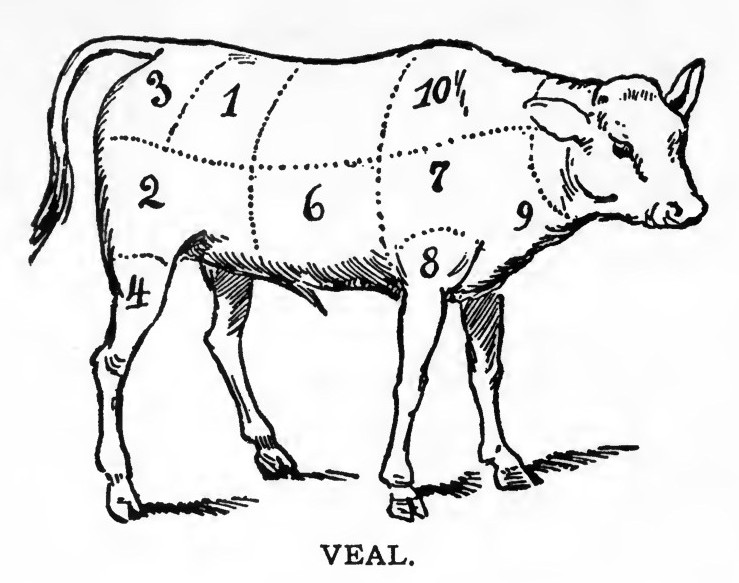

VEAL. HIND-QUARTER.

No.

1. Loin, the choicest cuts used for roasts and chops.

No.

2. Fillet, used for roasts and cutlets.

No.

3. Loin, chump-end used for roasts and chops.

No.

4. The hind-knuckle or hock, used for stews, pot-pies, meat-pies.

FORE-QUARTER.

No.

5. Neck, best end used for roasts, stews and chops.

No.

6. Breast, best end used for roasting, stews and chops.

No.

7. Blade-bone, used for pot-roasts and baked dishes.

No.

8. Fore-knuckle, used for soups and stews.

No.

9. Breast, brisket-end used for baking, stews and pot-pies.

No.

10. Neck, scrag-end used for stews, broth, meat-pies, etc.

In cutting up

veal, generally, the hind-quarter is divided into loin and leg, and the

fore-quarter into breast, neck and shoulder.

The Several

Parts of a Moderately-sized, Well-fed Calf, about eight weeks old, are nearly

of the

following weights: Loin and chump, 18 lbs.; fillet, 12 1/2 lbs.;

hind-knuckle,

5 1/2 lbs.; shoulder, 11 lbs.; neck, 11 lbs.; breast, 9 lbs., and

fore-knuckle,

5 lbs.; making a total of 144 lbs. weight.

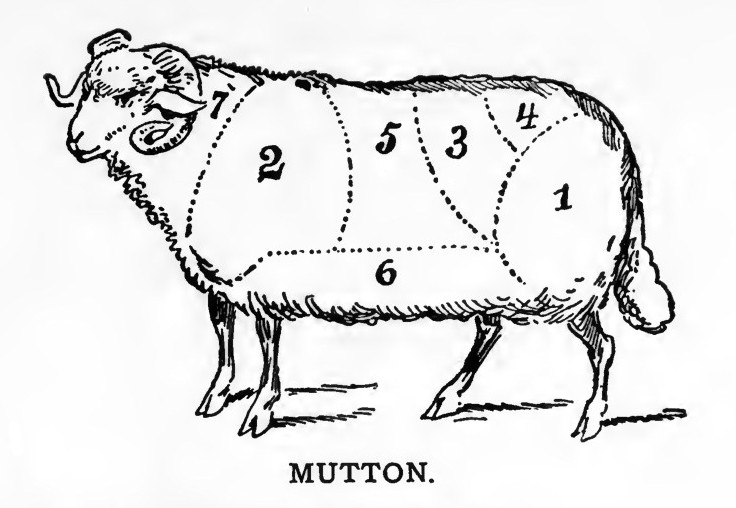

No.

1. Leg, used for roasts and for boiling.

No.

2. Shoulder, used for baked dishes and roasts.

No.

3. Loin, best end used for roasts, chops.

No.

4. Loin, chump-end used for roasts and chops.

No.

5. Back, or rib chops, used for French chops, rib chops, either

for

frying or broiling; also used for choice stews.

No.

6. Breast, used for roast, baked dishes, stews, chops.

No.

7. Neck or scrag-end, used for cutlets, stews and meat-pies.

NOTE. — A saddle

of muton or double loin is two loins cut off before the carcass is

split open

down the back. French chops are a small rib chop, the end of the bone

trimmed

off and the meat and fat cut away from the thin end, leaving the round

piece of

meat attached to the larger end, which leaves the small rib-bone bare.

Very

tender and sweet.

Mutton is prime

when cut from a carcass which has been fed out of doors, and allowed to

run

upon the hillside; they are best when about three years old. The fat

will then

be abundant, white and hard, the flesh juicy and firm, and of a clear

red

color.

For mutton

roasts, choose the shoulder, the saddle, or the loin or haunch. The leg

should

be boiled. Almost any part will do for broth.

Lamb born in the

middle of the winter, reared under shelter, and fed in a great measure

upon

milk, then killed in the spring, is considered a great delicacy, though

lamb is

good at a year old. Like all young animals, lamb ought to be thoroughly

cooked,

or it is most unwholesome.

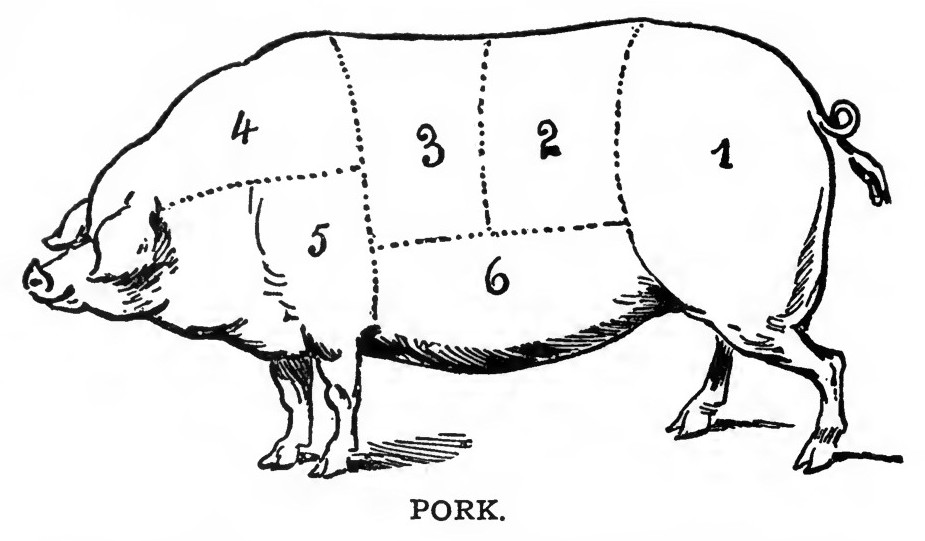

PORK

No.

1. Leg, used for smoked hams, roasts and corned pork.

No.

2. Hind-loin, used for roasts, chops and baked dishes.

No.

3. Fore-loin or ribs, used for roasts, baked dishes or chops.

No.

4. Spare-rib, used for roasts, chops, stews.

No.

5. Shoulder, used for smoked shoulder, roasts and corned pork.

No.

6. Brisket and flank, used for pickling in salt and smoked bacon.

The cheek is

used for pickling in salt, also the shank or shin. The feet are usually

used

for souse and jelly.

For family use

the leg is the most economical, that is when fresh, and the loin the

richest.

The best pork is from carcasses weighing from fifty to about one

hundred and

twenty-five pounds. Pork is a, white and close meat, and it is almost

impossible to over-roast or cook it too much; when underdone it is

exceedingly

unwholesome.

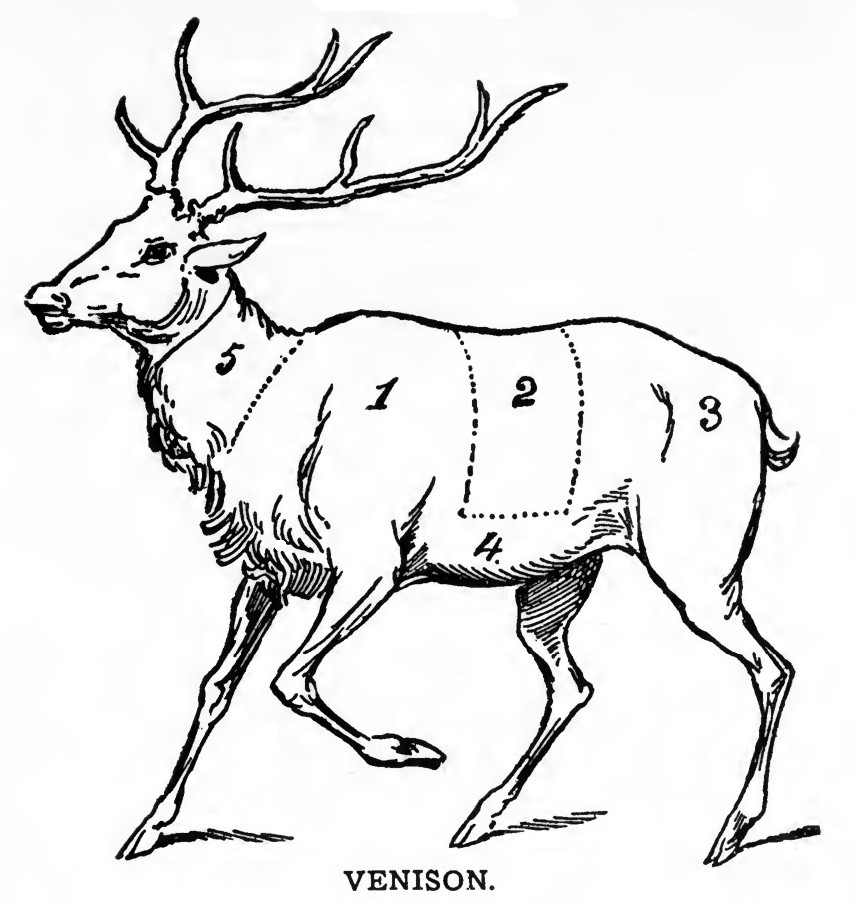

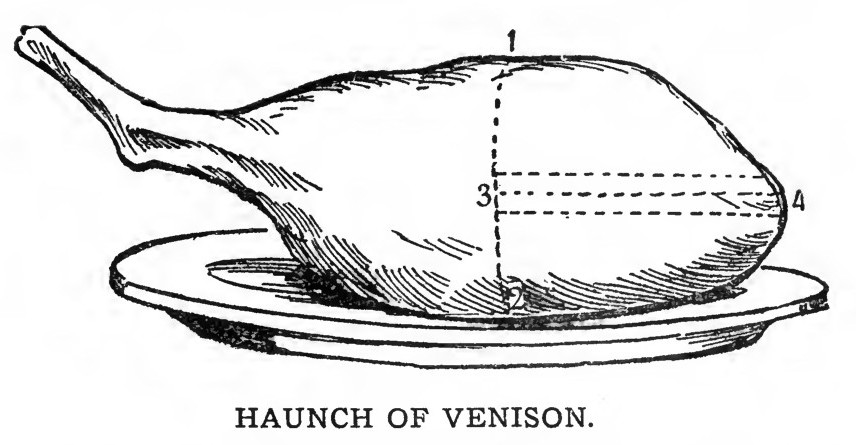

VENISON

No.

1. Shoulder, used for roasting; it may be boned and stuffed, then afterwards

baked or roasted.

No.

2. Fore-loin, used for roasts and steaks.

No.

3. Haunch or loin, used for roasts, steaks, stews. The ribs cut close

may be

used for soups. Good for pickling and making into smoked venison.

No.

4. Breast, used for baking dishes, stewing.

No.

5. Scrag or neck, used for soups.

The choice of

venison should be judged by the fat, which, when the venison is young,

should

be thick, clear and close, and the meat a very dark red, The flesh of a

female

deer about four years old, is the sweetest and best of venison.

Buck venison,

which is in season from June to the end of September, is finer than doe

venison, which is in season from October to December. Neither should be

dressed

at any other time of year, and no meat requires so much care as venison

in

killing, preserving and dressing.

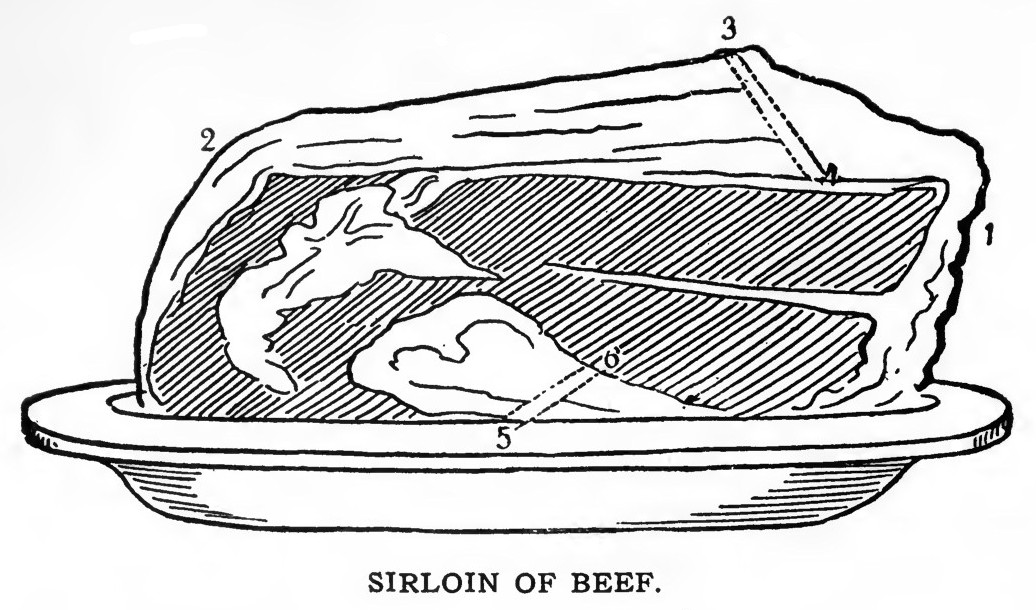

SIRLOIN OF BEEF

THIS choice

roasting-piece should be cut with one good firm stroke from end to end

of the

joint, at the upper part, in thin, long, even slices in the direction

of the

line from 1 to 2, cutting across the grain, serving each guest with

some of the

fat with the lean; this may be done by cutting a small, thin slice from

underneath the bone from 5 to 6, through the tenderloin.

Another way of

carving this piece, and which will be of great assistance in doing it

well, is

to insert the knife just above the bone at the bottom, and run sharply

along,

dividing the meat from the bone at the bottom and end, thus leaving it

perfectly flat; then carve in long, thin slices the usual way. When the

bone

has been removed and the sirloin rolled before it is cooked, it is laid

upon

the platter on one end, and an even, thin slice is carved across the

grain of

the upper surface.

Roast ribs

should be carved in thin, even slices from the thick end towards the

thin in

the same manner as the sirloin; this can be more easily and cleanly

done if the

carving knife is first run along between the meat and the end and

rib-bones,

thus leaving it free from bone to be cut into slices.

Tongue. — To carve this it should

be cut crosswise, the middle being the best; cut in very thin slices,

thereby

improving its delicacy, making it more tempting; as is the case of all

well-carved meats. The root of the tongue is usually left on the

platter.

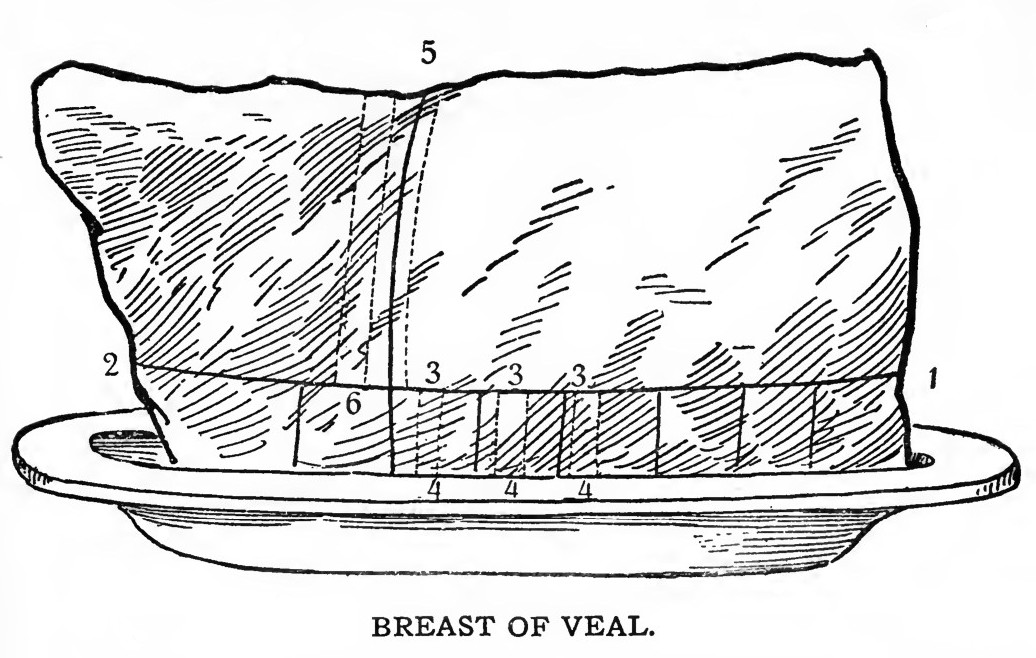

BREAST OF VEAL

THIS piece is

quite similar to a fore-quarter of lamb after the shoulder has been

taken off.

A breast of veal consists of two parts, the rib-bones and the gristly

brisket.

These parts may be separated by sharply passing the carving knife in

the

direction of the line from 1 to 2; and when they are entirely divided,

the

rib-bones should be carved in the direction of the line from 5 to 6,

and the

brisket can be helped by cutting slices from 3 to 4.

The carver

should ask the guests whether they have a preference for the brisket or

ribs;

and if there be a sweetbread served with the dish, as is frequently

with this

roast of veal, each person should receive a piece.

Though veal and

lamb contain less nutrition than beef and mutton, in proportion to

their

weight, they are often preferred to these latter meats on account of

their

delicacy of texture and flavor. A whole breast of veal weighs from nine

to

twelve pounds.

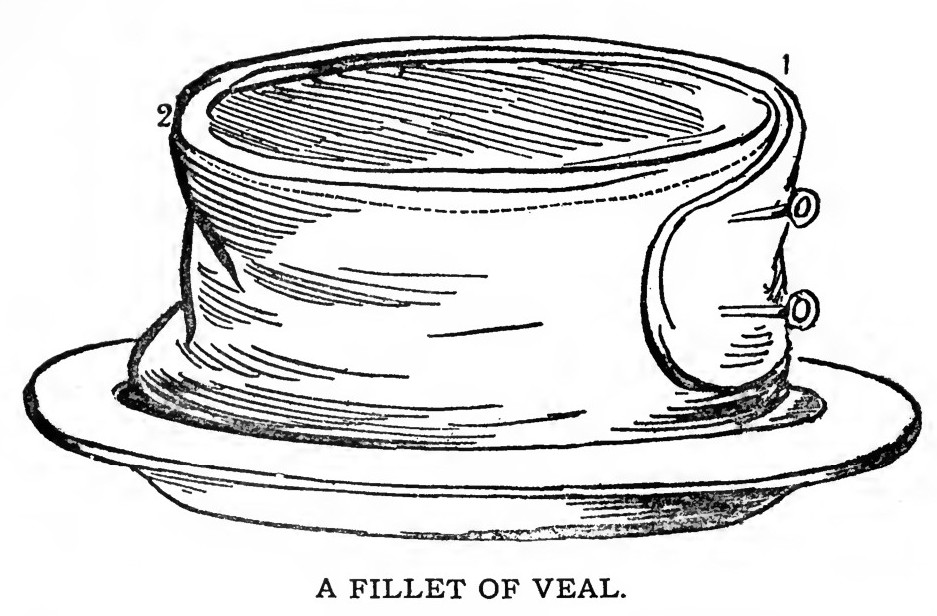

FILLET OF VEAL

A FILLET of veal

is one of the prime roasts of veal; it is taken from the leg above the

knuckle;

a piece weighing from ten to twelve pounds is a good size and requires

about

four hours for roasting. Before roasting, it is dressed with a force

meat or

stuffing placed in the cavity from where the bone was taken out and the

flap

tightly secured together with skewers; many bind it together with tape.

To carve it, cut

in even thin slices off from the whole of the upper part or top, in the

same

manner as from a rolled roast of beef, as in the direction of the figs.

1 and

2; this gives the person served some of the dressing with each slice of

meat.

Veal is very

unwholesome unless it is cooked thoroughly, and when roasted should be

of a

rich brown color. Bacon, fried pork, sausage balls, with greens, are

among the

accompaniments of roasted veal, also a cut lemon.

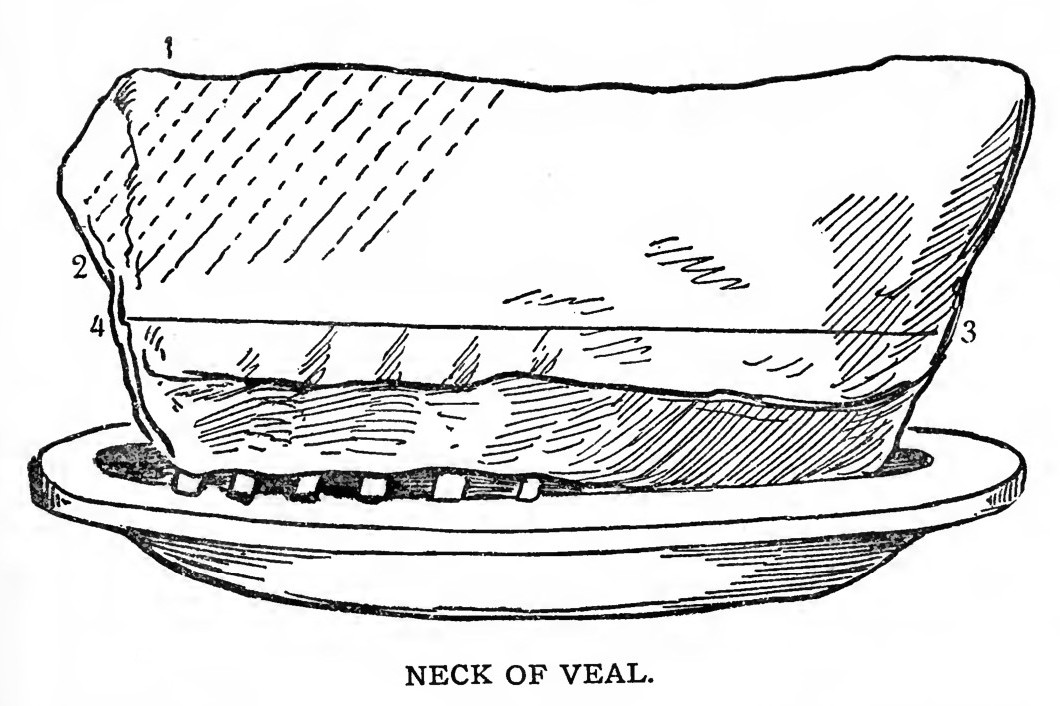

NECK OF VEAL

THE best end of

a neck of veal makes a very good roasting-piece; it, however, is

composed of

bone and ribs that make it quite difficult to carve, unless it is done

properly. To attempt to carve each chop and serve it, you would not

only place

too large a piece upon the plate of the person you intend to serve, but

you

would waste much time, and should the vertebras have not been removed

by the

butcher, you would be compelled to exercise such a degree of strength

that

would make one's appearance very ungraceful, and possibly, too,

throwing gravy

over your neighbor sitting next to you. The correct way to carve this

roast is to

cut diagonally from fig. 1 to 2, and help in slices of moderate

thickness; then

it may be cut from 3 to 4, in order to separate the small bones; divide

and

serve them, having first inquired if they are desired.

This joint is

usually sent to the table accompanied by bacon, ham, tongue, or pickled

pork,

on a separate dish and with a cut lemon on a plate. There are also a

number of

sauces that are suitable with this roast.

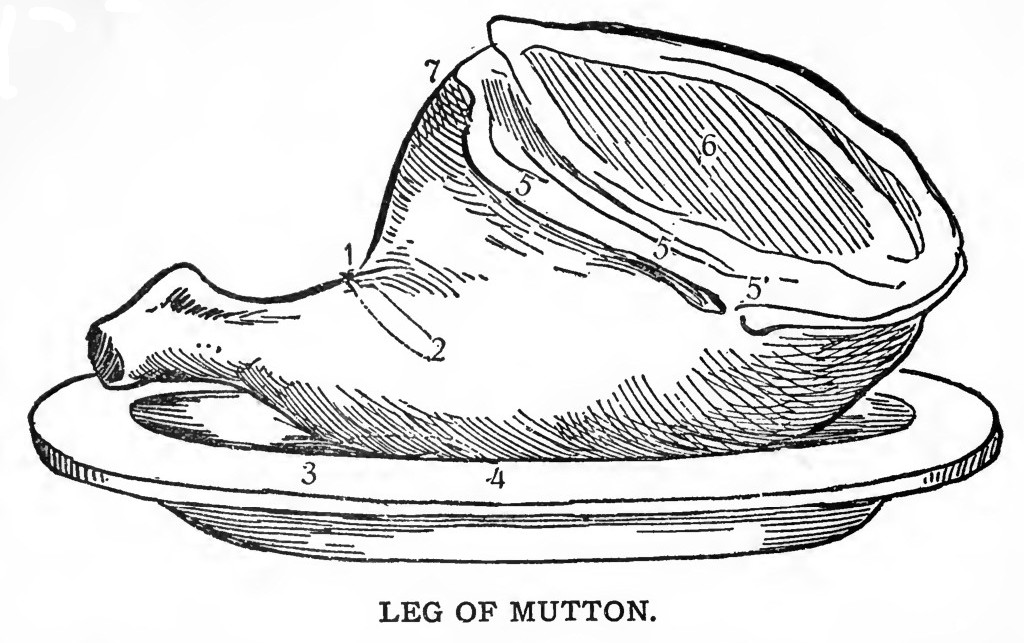

LEG OF MUTTON

THE best mutton,

and that from which most nourishment is obtained is that of sheep from

three to

six years old, and which have been fed on dry, sweet pastures; then

mutton is

in its prime, the flesh being firm, juicy, dark colored and full of the

richest

gravy. When mutton is two years old, the meat is flabby, pale and

savorless.

In carving a

roasted leg, the best slices are found by cutting quite down to the

bone, in

the direction from 1 to 2, and slices may be taken from either side.

Some very good

cuts are taken from the broad end from 5 to 6, and the fat on this

ridge is

very much liked by many. The cramp-bone is a delicacy, and is obtained

by

cutting down to the bone at 4, and running the knife under it in a

semicircular

direction to 3. The nearer the knuckle the drier the meat, but the

under side

contains the most finely grained meat, from which slices may be cut

lengthwise.

When sent to the table a frill of paper around the knuckle will improve

its

appearance.

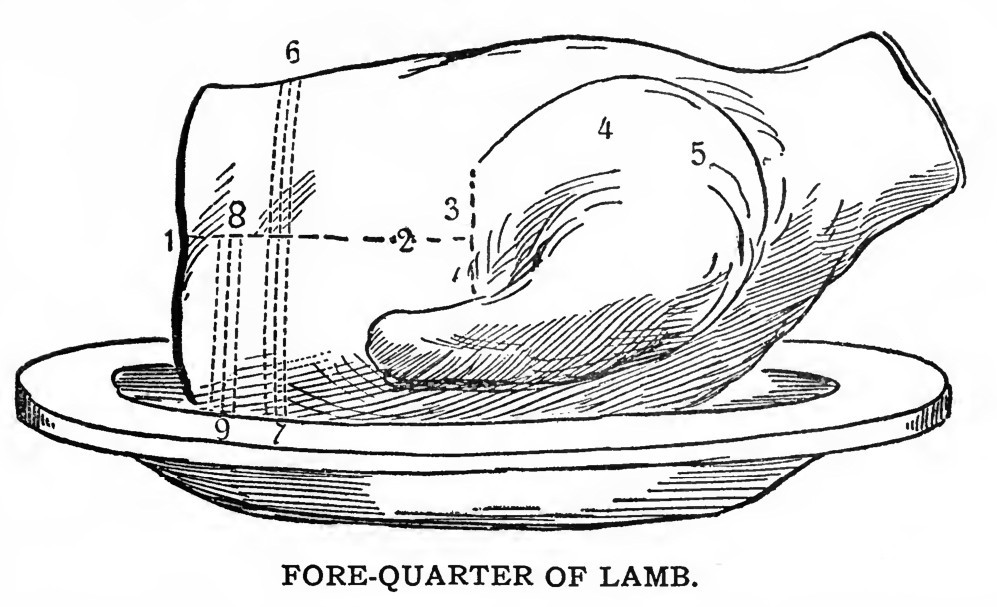

FOREQUARTER OF LAMB

THE first cut to

be made in carving a fore-quarter of lamb is to separate the shoulder

from the breast

and ribs; this is done by passing a sharp carving knife lightly around

the

dotted line as shown by the figs. 3, 4 and 5, so as to cut through the

skin,

and then, by raising with a little force the shoulder, into which the

fork

should be firmly fixed, it will easily separate with just a little more

cutting

with the knife; care should be taken not to cut away too much of the

meat from

the breast when dividing the shoulder from it, as that would mar its

appearance. The shoulder may be placed upon a separate dish for

convenience.

The next process is to divide the ribs from the brisket by cutting

through the

meat in the line from 1 to 2; then the ribs may be carved in the

direct-ion of

the line 6 to 7, and the brisket from 8 to 9. The carver should always

ascertain

whether the guest prefers ribs, brisket, or a piece of the shoulder.

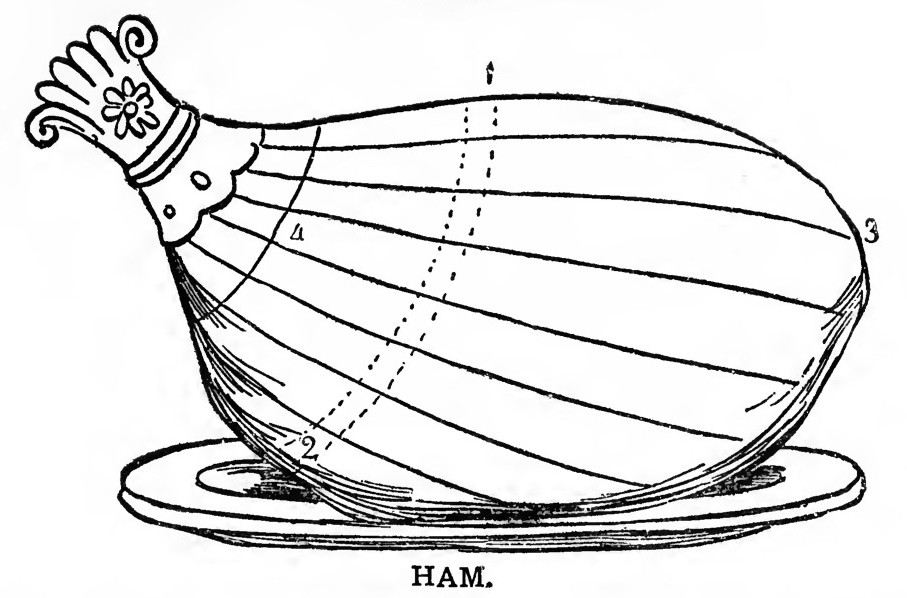

HAM

THE carver in

cutting a ham must be guided according as he desires to practice

economy, or

have at once fine slices out of the prime part. Under the first

supposition, he

will commence at the knuckle end, and cut off thin slices toward the

thick and

upper part of the ham.

To reach the

choicer portion of the ham, the knife, which must be very sharp and

thin,

should be carried quite down to the bone through the thick fat in the

direction

of the line from 1 to 2, The slices should be even and thin, cutting

both lean

and fat together, always cutting down to the bone. Some cut a circular

hole in

the middle of a ham gradually enlarging it outwardly. Then again many

carve a ham

by first cutting from 1 to 2, then across the other way from 3 to 4.

Remove the

skin after the ham is cooked and send to the table with dots of dry

pepper or

dry mustard on the top, a tuft of fringed paper twisted about the

knuckle, and

plenty of fresh parsley around the dish. This will always insure an

inviting

appearance.

Roast Pig. — The modern way of

serving a pig is not to send it to the table whole, but have it carved

partially by the cook; first, by dividing the shoulder from the body;

then the

leg in the same manner, also separating the ribs into convenient

portions. The

head may be divided and placed on the same platter. To be served as hot

as

possible.

A Spare Rib of

Pork is carved by cutting slices from the fleshy part, after which the

bones should

be disjointed and separated. A leg of pork may be carved in the same

manner as

a ham.

HAUNCH OF VENISON

A HAUNCH of

venison is the prime joint, and is carved very similar to almost any

roasted or

boiled leg; it should be first cut crosswise down to the bone following

the

line from 1 to 2; then turn the platter with the knuckle farthest from

you, put

in the point of the knife, and cut down as far as you can, in the

directions

shown by the dotted lines from 3 to 4; then there can be taken out as

many

slices as is required on the right and left of this. Slices of venison

should

be cut thin, and gravy given with them, but as there is a special sauce

made

with red wine and currant jelly to accompany this meat, do not serve

gravy

before asking the guest if he pleases to have any.

The fat of this

meat is like mutton, apt to cool soon, and become hard and disagreeable

to the

palate; it should, therefore, be served always on warm plates, and the

platter

kept over a hot-water dish, or spirit lamp. Many cooks dish it up with

a white

paper frill pinned around the knuckle bone.

A haunch of

mutton is carved the same as a haunch of venison.

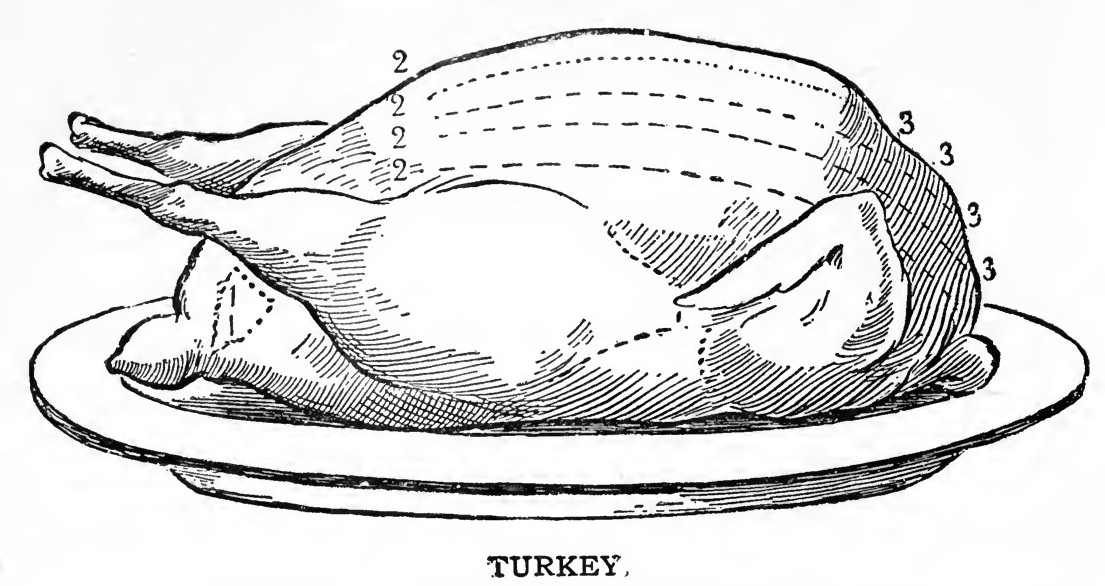

TURKEY

A TURKEY having

been relieved from strings and skewers used in trussing should be

placed on the

table with the head or neck at the carver's right hand. An expert

carver places

the fork in the turkey, and does not remove it until the whole is

divided.

First insert the fork firmly in the lower part of the breast, just

forward of

fig. 2, then sever the legs and wings on both sides, if the whole is to

be

carved, cutting neatly through the joint next to the body, letting

these parts

lie on the platter. Next, cut downward from the breast from 2 to 3 as

many even

slices of the white meat as may be desired, placing the pieces neatly

on one

side of the platter. Now un joint the legs and wings at the middle

joint, which

can be done very skillfully by a little practice. Make an opening into

the

cavity of the turkey for dipping out the inside dressing, by cutting a

piece

from the rear part 1, 1, called the apron. Consult the tastes of the

guests as

to which part is preferred; if no choice is expressed, serve a portion

of both

light and dark meat. One of the most delicate parts of the turkey are

two

little muscles, lying in small dish-like cavities on each side of the

back, a

little behind the leg attachments; the next most delicate meat fills

the

cavities in the neck bone, and next to this, that on the second joints.

The

lower part of the leg (or drumstick, as it is called) being hard, tough

and

stringy, is rarely ever helped to any one, but allowed to remain on the

dish.

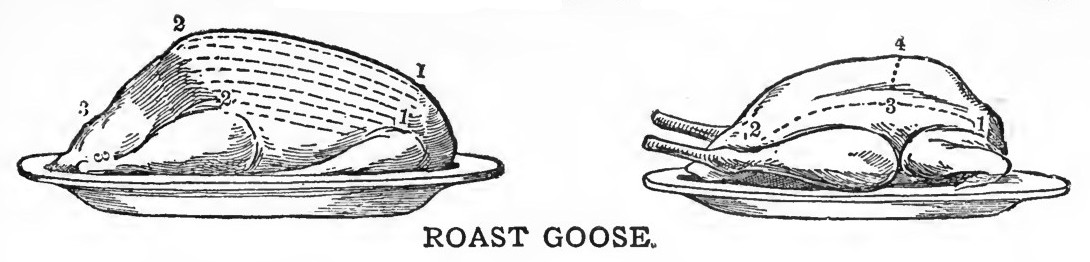

ROAST GOOSE

TO CARVE a

goose, first begin by separating the leg from the body, by putting the

fork

into the small end of the limb, pressing it closely to the body, then

passing the

knife under at 2, and turning the leg back as you cut through the

joint. To

take off the wing, insert the fork in the small end of the pinion, and

press it

close to the body; put the knife in at fig. 1, and divide the joint.

When the

legs and wings are off, the breast may be carved in long, even slices,

as

represented in the lines from 1 to 2. The back and lower side bones, as

well as

the two lower side bones by the wing, may be cut off; but the best

pieces of

the goose are the breast and thighs, after being separated from the

drumsticks.

Serve a little .of the dressing from the inside, by making a circular

slice in

the apron at fig. 3. A goose should never be over a year old; a tough

goose is

very difficult to carve, and certainly most difficult to eat.

FOWLS.

FIRST insert the

knife between the leg and the body, and cut to the bone; then turn the

leg back

with the fork, and if the fowl is tender the joint will give away

easily. The

wing is broken off the same way, only dividing the joint with the

knife, in the

direction from 1 to 2, The four quarters having been removed in this

way, take

off the merry-thought and the neck-bones; these last are to be removed

by

putting the knife in at figs. 3 and 4, pressing it hard, when they will

break

off from the part that sticks to the breast To separate the breast from

the

body of the fowl, cut through the tender ribs close to the breast,

quite down

to the tail. Now turn the fowl over, back upwards; put the knife into

the bone

midway between the neck and the rump, and on raising the lower end it

will

separate readily. Turn now the rump from you, and take off very neatly

the two

side bones, and the fowl is carved. In separating the thigh from the

drumstick,

the knife must be inserted exactly at the joint, for if not accurately

hit,

some difficulty will be experienced to get them apart; this is easily

acquired

by practice. There is no difference in carving roast and boiled fowls

if full

grown; but in very young fowls the breast is usually served whole; the

wings

and breast are considered the best parts, but in young ones the legs

are the

most juicy. In the case of a capon or large fowl, slices may be cut off

at the

breast, the same as carving a pheasant.

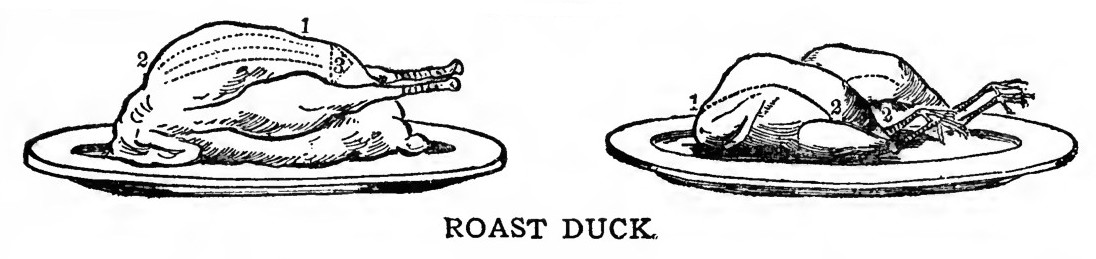

ROAST DUCK

A YOUNG duckling

may be carved in the same manner as a fowl, the legs and wings being

taken oft

first on either side. When the duck is full size, carve it like a

goose; first

cutting it in slices from the breast, beginning close to the wing and

proceeding upward towards the breast bone, as is represented by the

lines 1 to

2. An opening may be made by cutting out a circular slice, as shown by

the

dotted lines at number 3.

Some are fond of

the feet, and when dressing the duck, these should be neatly skinned

and never

removed. Wild duck is highly esteemed by epicures; it is trussed like a

tame

duck, and carved in the same manner, the breast being the choicest part.

PARTRIDGES.

PARTRIDGES are

generally cleaned and trussed the same way as a pheasant, but the

custom of

cooking them with the heads on is going into disuse somewhat. The usual

way of

carving them is similar to a pigeon, dividing it into two equal parts.

Another

method is to cut it into three pieces, by severing a wing and leg on

either

side from the body, by following the lines 1 to 2, thus making two

servings of

those parts, leaving the breast for a third plate. The third method is

to

thrust back the body from the legs, and cut through the middle of the

breast,

thus making four portions that may be served. Grouse and

prairie-chicken are

carved from the breast when they are large, and quartered or halved

when of

medium size.

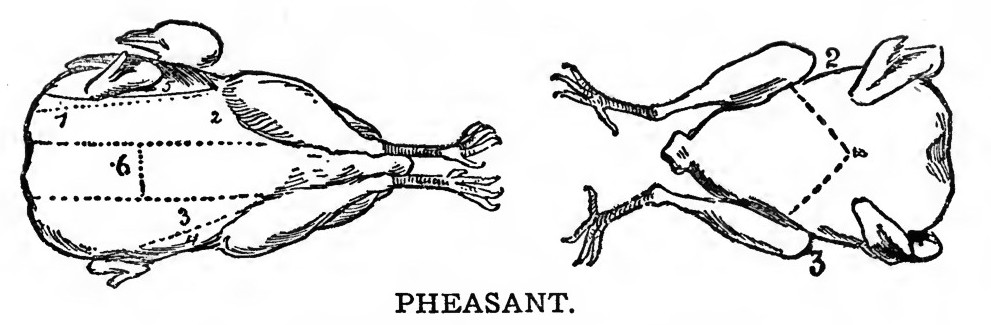

PHEASANT

PLACE your fork

firmly in the centre of the breast of this large game bird and cut deep

slices

to the bone at figs. 1 and 2; then take off the leg in the line from 3

and 4,

and the wing 3 and 5, severing both sides the same. In taking off the

wings, be

careful not to cut too near the neck; if you do you will hit upon the

neck-bone, from which the wing must be separated. Pass the knife

through the

line 6, and under the merry-thought towards the neck, which will detach

it. Cut

the other parts as in a fowl. The breast, wings and merry-thought of a

pheasant

are the most highly prized, although the legs are considered very

finely

flavored. Pheasants are frequently roasted with the head left on; in

that case,

when dressing them, bring the head round under the wing, and fix it on

the

point of a skewer.

PIGEONS.

A VERY good way

of carving these birds is to insert the knife at fig. 1, and cut both

ways to 2

and 3, when each portion may be divided into two pieces, then served.

Pigeons,

if not too large, may be cut in halves, either across or down the

middle,

cutting them into two equal parts; if young and small they may be

served

entirely whole.

Tame pigeons

should be cooked as soon as possible after they are killed, as they

very

quickly lose their flavor. Wild pigeons, on the contrary, should hang a

day or

two in a cool place before they are dressed. Oranges cut into halves

are used

as a garnish for dishes of small birds, such as pigeons, quail,

woodcock,

squabs, snipe, etc. These small birds are either served whole or split

down the

back, making two servings.

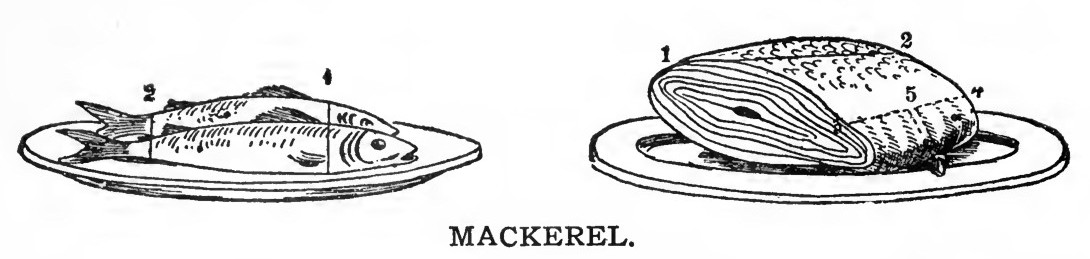

MACKEREL

THE mackerel is

one of the most beautiful of fish, being known by its silvery

whiteness. It

sometimes attains to the length of twenty inches, but usually, when

fully

grown, is about fourteen or sixteen inches long, and about two pounds

in

weight. To carve a baked mackerel, first remove the head and tail by

cutting

downward at 1 and 2; then split them down the back, so as to serve each

person

a part of each side piece. The roe should be divided in small pieces

and served

with each piece of fish. Other whole fish may be carved in the same

manner. The

fish is laid upon a little sauce or folded napkin, on a hot dish, and

garnished

with parsley.

BOILED

SALMON.

THIS fish is

seldom sent to the table whole, being too large for any ordinary sized

family;

the middle cut is considered the choicest to boil. To carve it, first

run the

knife down and along the upper side of the fish from 1 to 2, then again

on the

lower side from 3 to 4. Serve the thick part, cutting it lengthwise in

slices

in the direction of the line from 1 to 2, and the thin part

breadthwise, or in

the direction from 5 to 6. A slice of the thick with one of the thin,

where

lies the fat, should be served to each guest. Care should be taken when

carving

not to break the flakes of the fish, as that impairs its appearance.

The flesh

of the salmon is rich and delicious in flavor. Salmon is in season from

the

first of February to the end of August.

|