| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2011 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER

VII.

A

journey in search of new plants — Japanese College — Residence of

Prince Kanga — Dang-o-zaka — Its tea-gardens, fish-ponds, and

floral ladies — Nursery-gardens — Country people — Another

excursion — Soldiers — Arrive at Su-mae-yah — Country covered

with gardens — New plants — Mode of dwarfing — Variegated

plants — Ogee, the Richmond of Yedo — Its tea-house — The

Tycoon's hunting-ground — Fine views — Agricultural productions —

A drunken man — Intemperance of the people generally.

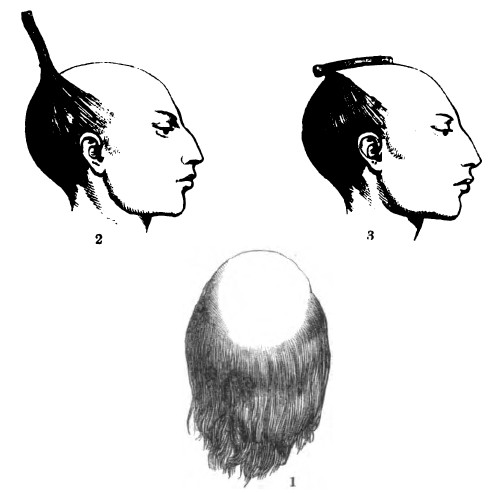

THE capital of Japan is remarkable for the large number of gardens in its suburbs where plants are cultivated for sale. The good people of Yedo, like all highly civilized nations, are fond of flowers, and hence the demand for them is very great. The finest and most extensive of these gardens are situated in the north-eastern suburbs, at places called Dang-o-zaka, Ogee, and Su-mae-yah. As one of my chief objects in coming to Yedo was to examine such places as these, I lost no time in paying them a visit. As the British Legation was situated in the south-west suburb, I had to cross the entire city before I could reach these gardens. From the time occupied in going this distance I estimated the width of the city, in this direction, at about nine or ten miles. Passing in from the western suburb, I went through the "Official Quarter," with its wide straight streets and town residences of the Daimios or lords and princes of the Empire, which have been already noticed. On a rising ground on my left I observed the palace of the Tycoon. Proceeding onward in an easterly direction, I recrossed the moat, and was again amongst the streets and shops of the common people. Here, on a hill-side, in the midst of some tall pines and evergreen oaks, I observed a large building, which, I was informed, was a college for students of Chinese classics. A little further on I passed the palace of the Prince of Kanga, reputed to be the wealthiest and most powerful noble in the empire, and to have no less than 40,000 retainers located in his palaces in the capital, ready to do his bidding, whether that be to dethrone the Tycoon or to take the life of a foreigner. He was reported to be at the head of the conservative party in the empire, and to be unfavourable to foreigners. After passing the residence of Prince Kanga I found myself in the eastern suburb. One long street, with houses on each side of the way, and detached towns here and there, extended two or three miles beyond this. Turning out of this street to the right hand, I passed through some pretty shaded lanes, and in a few minutes more reached the romantic town of Dang-o-zaka. This pretty place is situated in a valley, having wooded hills on either side, with gardens, fish-ponds, and tea-houses in the glen and on the sides of the hills. In the principal tea-gardens the fish-ponds are stocked with different kinds of fish; and I observed a number of anglers amusing themselves fishing, in the usual way, with hooks baited with worms. The most curious objects in this garden were imitation ladies made up out of the flowers of the chrysanthemum. Thousands of flowers were used for this purpose; and as these artificial beauties smiled upon the visitors out of the little alcoves and summer houses, the effect was oftentimes rather startling. The favourite flowering plum-trees were planted in groups and avenues in all parts of the garden, while little lakes and islands of rockwork added to the general effect. Having patronised this establishment by taking sundry cups of tea, I intimated to my attendant yakoneens my intention to look out for some gardens of a different kind, in which I could purchase some new plants. But pleasure was the order of the day with them, and they coolly informed me there were no other places worth seeing here, and that we had better go on to the tea-gardens of Ogee. From information I had previously received, I knew they were deceiving me, and therefore proceeded to take a general survey on my own account. When they saw I was determined to look out for myself, they pretended to have received some information about other places, and said they were willing to guide me to them. Telling them I was greatly obliged, I desired them to lead the way. A short walk to the top of the hill brought us to a long, straight, country-looking road, lined with neatly clipped hedges. Here I found a large number of nursery gardens, richly stocked with the ornamental plants of the country. Crowds of people followed us, and, although they were rather noisy, and anxious to see such a strange sight as a foreigner in these out-of-the-way places, they were, upon the whole, particularly civil and easily managed and controlled. As I entered a nursery the gates were quietly closed upon the people, who waited patiently until I came out, and then they followed me on to the next. The yakoneens seemed to be greatly respected, or feared it may be, but, at all events, a look, a word, or a movement of the fan, was quite sufficient to preserve the most perfect order. I visited garden after garden in succession. Each was crowded with plants, some cultivated in pots and others in the open ground, many of which were entirely new to Europe, and of great interest and value. Every now and then my yakoneens informed me that the garden I happened to be in at the time was the last one in the lane, but I told them good-humouredly I would go on a little further and satisfy myself. This they could not object to, and, as more gardens were found, they only smiled and said they had been misinformed. My old experience in China was of good service to me here. There is nothing like patience, politeness, and good humour, with these Orientals, whether they present themselves as noisy crowds or crafty officials. At first the proprietors were not quite sure whether they ought to sell me the plants which I selected. A reference was invariably made to the yakoneens, both upon this point and also as to what sum they should ask. I am afraid I must confess to the impression that these gentry made me pay considerably more than the fair value or "market price." As I concluded each purchase, the plants purchased, the price, and the name of the vendor, were carefully written down by one of the officials, and this report of my proceedings was taken home to their superiors. The day was far spent before I had finished the inspection of these interesting gardens, but I was greatly pleased with the results. A great number of new shrubs and trees, many of them probably well suited for our English climate, had been purchased. Orders were now given to the different nurserymen to bring the plants to the English Legation on the following day, and we parted mutually pleased with our bargains. It was now too late to go to Ogee or Su-mae-yah, so that journey was put off until another day. Mounting our horses, we left the pleasant and romantic lanes of Dang-o-zaka and rode homewards. In coming out we had passed to the south of the Tycoon's palace, but in going home a different route was taken — a route which led us along the north side of these buildings. In all my excursions about Yedo with a guard of yakoneens, I have invariably observed that they have brought me home by a different road from that by which I went. At first I gave them credit for a desire to show me as much of the city as possible, but I am now inclined to believe that they had orders of this kind from their superiors; and that the object was to prevent the chance of an attack from any one who had seen us going out, and who might lie in wait for us on our return. Be that as it may, the fact is as I have stated. On the following morning the whole of the nurserymen from whom I had purchased plants presented themselves at the British Legation, to deliver the plants and to receive their money — and possibly to pay a small tax to the officials. But if the latter transaction took place, it was done quietly and without a murmur. A day or two after this, with a flask of wine slung over my shoulder, and a small loaf and jar of potted meat in my pocket, I started early in the morning in order to explore the country and gardens about Su-mae-yah and Ogee. The same guard of yakoneens accompanied me, and our road, for a good part of the way, was the same as that by which I went to Dang-o-zaka. The places we now proposed to visit, although in the same direction, are considerably farther off. Passing, therefore, the scene of my former visit, I rode onwards farther out into the suburbs. The houses gradually began to get more scattered, sometimes fields and trees lined one side of the road, and everything showed me that I had fairly left the great city behind me. In one of these country parks I heard some soldiers going through their exercise; and the music was not unlike that of our own military bands. It was, very likely an imitation of something of the kind. The high close paling and dense brushwood prevented me from seeing much, but sometimes I caught a glimpse of the flags and spears of the soldiers. The Daimios are constantly training their soldiers in all the arts of Japanese warfare. On this occasion, when passing near a Daimio's residence in the city, I heard the clattering of arms, as of men engaged in fencing; and many times, during my stay in Yedo, I have heard the same sounds. If ever any European nation has the misfortune to go to war with Japan, it will find the Japanese, as soldiers, very much superior to the Chinese. At the same time, as we do not fight with swords only, there is little doubt about the issue of such a contest. Let us hope, however, that such a thing as a war with Japan may be far distant, and that, in this one instance at least, we may have the satisfaction of opening up a country without deluging it with the blood of its people. Park-like scenery, trees and gardens, neatly-clipped hedges, succeeded each other; and my attendant yakoneens at length announced that we had arrived at the village of Su-mae-yah. The whole country here is covered with nursery-gardens. One straight road, more than a mile in length, is lined with them. I have never seen, in any part of the world, such a large number of plants cultivated for sale. Each nursery covers three or four acres of land, is nicely kept, and contains thousands of plants, both in pots and in the open ground. As these nurseries are generally much alike in their features, a description of one will give a good idea of them all. On entering the gateway there is a pretty little winding path leading up to the proprietor's house, which is usually situated near the centre of the garden. On each side of this walk are planted specimens of the hardy ornamental trees and shrubs of the country, many of which are dwarfed or clipped into round table forms. The beautiful little yew (Taxus cuspidata) which I formerly introduced into Europe from China, occupies a prominent place amongst dwarf shrubs. Then there are the different species of Pines, Thujas, Retinosporas, and the beautiful Sciadopitys verticillata, all duly represented. Plants cultivated in pots are usually kept near the house of the nurseryman, or enclosed with a fence of bamboo-work. These are cultivated and arranged much in the same way as we do such things at home. The Japanese gardener has not yet brought glass-houses to his aid for the protection and cultivation of tender plants. Instead of this he uses sheds and rooms fitted with shelves, into which all the tender things are huddled together for shelter during the cold months of winter. Here I observed some South American plants, such as cacti, aloes, &c., which have found their way here, although as yet unknown in China — a fact which shows the enterprise of the Japanese in a favourable light. A pretty species of fuchsia was also observed amongst the other foreigners. In one garden I saw a large number of a species of acorus with deep green leaves. These were cultivated in fine square porcelain pots, and in each pot was a little rock of agate, crystal, or other rare stone, many of these representing the famous Fusi-yama, or "Matchless Mountain" of Japan. All this little arrangement was shaded from bright sunshine and protected from storms by means of a matting which was stretched overhead. There was nothing else in this garden but the acorus above mentioned, but of this there must have been several hundred specimens. The pretty Nanking square porcelain pots, the masses of deep green foliage, and the quaint form and colouring of the little rocks, produced a novel and striking effect, which one does not meet with every day. In Japan, as in China, dwarf plants are greatly esteemed; and the art of dwarfing has been brought to a high state of perfection. President Meylan, in the year 1826, saw a box which he describes as only one inch square by three inches high, in which were actually growing and thriving a bamboo, a fir, and a plum-tree, the latter being in full blossom. The price of this portable grove was 1200 Dutch gulden, or about 100l. In the gardens of Su-macyah dwarf plants were fairly represented, although I did not meet with anything so very small and very expensive as that above mentioned. Pines, junipers, thujas, bamboos, cherry and plum trees, are generally the plants chosen for the purpose of dwarfing. The art of dwarfing trees, as commonly practised both in China and Japan, is in reality very simple and easily understood. It is based upon one of the commonest principles of vegetable physiology. Anything which has a tendency to check or retard the flow of the sap in trees, also prevents, to a certain extent, the formation of wood and leaves. This may be done by grafting, by confining the roots in a small space, by withholding water, by bending the branches, and in a hundred other ways, which all proceed upon the same principle. This principle is perfectly understood by the Japanese, and they take advantage of it to make nature subservient to this particular whim of theirs. They are said to select the smallest seeds from the smallest plants, which I think is not at all unlikely. I have frequently seen Chinese gardeners selecting suckers for this purpose from the plants of their gardens. Stunted varieties were generally chosen, particularly if they had the side branches opposite or regular, for much depends upon this; a one-sided dwarf-tree is of no value in the eyes of the Chinese or Japanese. The main stem was then, in most cases, twisted in a zigzag form, which process checked the flow of the sap, and at the same time encouraged the production of side-branches at those parts of the stem where they were most desired. The pots in which they were planted were narrow and shallow, so that they held but a small quantity of soil compared with the wants of the plants, and no more water was given than was actually necessary to keep them alive. When new branches were in the act of formation they were tied down and twisted in various ways; the points of the leaders and strong-growing ones were generally nipped out, and every means were taken to discourage the production of young shoots possessing any degree of vigour. Nature generally struggles against this treatment for a while, until her powers seem to be in a great measure exhausted, when she quietly yields to the power of Art. The artist, however, must be ever on the watch; for should the roots of his plants get through the pots into the ground, or happen to receive a liberal supply of moisture, or should the young shoots be allowed to grow in their natural position for a time, the vigour of the plant, which has so long been lost, will be restored, and the fairest specimens of Oriental dwarfing destroyed. It is a curious fact that when plants, from any cause, become stunted or unhealthy, they almost invariably produce flowers and fruit, and thus endeavour to propagate and perpetuate their kind. This principle is of great value in dwarfing trees. Flowering trees — such, for example, as peaches and plums — produce their blossoms most profusely under the treatment I have described; and as they expend their energies in this way, they have little inclination to make vigorous growth. The most remarkable feature in the nurseries of Su-mae-yah and Dang-o-zaka is the large number of plants with variegated leaves. It is only a very few years since our taste in Europe led us to take an interest in and to admire those curious freaks of nature called variegated plants. For anything I know to the contrary, the Japanese have been cultivating this taste for a thousand years. The result is that they have in cultivation, in a variegated state, almost all the ornamental plants of the country, and many of these are strikingly handsome. Here is a list of a few to give some idea of the extent and number of these extraordinary productions: — Pines, Junipers, Retinosporas, Podocarpus, Illiciums, Andromeda japonica, Euryas, Eleagnus, Pittosporum Tobira, Euonymus (yellow), Aralia, Laurus, Salisburia adiantifolia. I have already said we must look upon the Aucuba japonica of our gardens as only a variegated variety of that species. Then there is a variegated orchid! a variegated palm! a variegated camellia! and even the tea-plant is duly represented in this "happy family!" The beautiful Sciadopitys verticillata, which is no doubt "one of the finest conifers in Asia," has produced a variety which has golden-striped leaves. It may readily be imagined that I was able to select a great number of new ornamental shrubs and trees which will one day, it is hoped, produce a striking and novel effect upon our English parks and pleasure-grounds. Having settled the prices of the different plants selected, all the particulars were carefully written down by my attendant yakoneens, as on a former occasion, and the vendors were requested to bring my purchases to the British Legation on the following morning. We then took our departure for Ogee. Ogee is the Richmond of Japan, and its celebrated tea-house is a sort of "Star and Garter Hotel." Here the good citizens of Yedo come out for a day's pleasure and recreation, and certainly it would be difficult to find a spot more lovely or more enjoyable. Our road led us down a little hill, and was lined on each side with pretty suburban residences, gardens, and hedgerows. On approaching the village crowds of people came out to look at the foreigner, although a species of that genus had not been particularly rare of late. Giving some of the boys our horses to hold, we were conducted to the interior of the tea-house, and attended by pretty, good-humoured damsels. A small garden, with a running stream overhung with the branches of trees, green banks, and lovely flowers, was in the rear of the tea-house; and, taken as a whole, the place was extremely pretty and well worthy of being patronized by the pleasure-seekers of Yedo. Having partaken of the cakes, tea, hard-boiled eggs, and other delicacies which were set before me, I went out for a stroll in the surrounding country. As my yakoneens were busy with their dinner, I tried to induce them to remain and finish it, telling them I was only going for a short walk, and that I would soon return. This they would not listen to, so I let them have their own way, and we all set out together. My chief object was to get upon the top of a hill in the vicinity, in order to have a good view of the country. A few minutes brought me to the top, which formed a kind of table-land, uncultivated, but having here and there a few groups of lofty trees. This forms the hunting-grounds of his Imperial Majesty the Tycoon. It is here that on certain occasions he watches the flight of the falcon in pursuit of the heron of Japan — a bird held sacred by the Japanese, and rigidly preserved by the authorities. There is also on this hill an archery-ground for the Imperial soldiers, and a refectory for preparing a repast for his Majesty's retinue. The view from the top of this eminence was exceedingly fine. To the northward, a highly cultivated agricultural country lay spread out. It was the period of the rice-harvest, and the fields were now yellow with the ripening grain. The young crops of wheat and barley, already several inches above ground, were of the liveliest green, and contrasted well with the yellow rice-fields. The country was well-wooded, and a little river was seen winding through the valley on its way to the head of the Yedo bay. Taking the place as a whole, his Majesty the Tycoon could scarcely have found a more pleasant hunting-ground. The day was now far advanced; indeed, my yakoneens had been hinting some time before this that it was time to return to Yedo. First, they looked to the heavens, and gravely informed me they thought it was going to rain; and when they saw this did not produce the desired effect, they told me evening was approaching, and that it was dangerous for me to be out after dark. This was no doubt quite true, and during my residence in Yedo I invariably made it a rule to get back to the Legation as soon after nightfall as possible. On the present occasion I intimated to them that I was now quite ready to return to the city, and we were soon on our way. On our way back, and just when we were opposite to the residence of the Prince of Kanga — the Daimio whom I have already mentioned as unfavourable to foreigners — a drunken man was monopolizing the road, who, I was afraid, might give us some trouble. He had a long wooden pole in his hands, and was endeavouring to strike all who came in his path. One of my betos, or grooms, was struck by him; but as the poor wretch could scarcely stand, it was very easy to get out of his way. He had no idea that a foreigner was behind him; and I shall never forget the peculiar wild and drunken stare he gave me when he observed me. Under the circumstances I judged it prudent to leave him in his trance of astonishment, and trotted onwards. Intemperance in the use of ardent spirits is one of the vices of the Japanese. In this respect, if we can trust Thunberg, the Swedish physician, they must have degenerated sadly during the last hundred years. Amongst a long catalogue of their virtues, Thunberg says, they have "no play or coffee-houses, no taverns nor alehouses, and consequently no consumption of coffee, chocolate, brandy, wine, or punch; no privileged soil, no waste lands, and not a single meadow; no national debt, no paper currency, no course of exchange, and no bankers(!)." It may have been so in Thunberg's time, although I confess to some doubts upon the subject; but it will be seen, from what came under my own observation, that things are very different now. In these days it is a common saying that "all Yedo gets drunk after sunset!" This is, of course, an exaggeration; but, no doubt, drunkenness prevails to a degree happily unknown in other countries at the present day. Even before the evening closes in, the faces of those one meets in the streets are suspiciously red, showing plainly enough that saki has been imbibed pretty freely. Nor is it in the capital city only that such a state of things exists. We learn from Dr. Pompe, the Dutch physician at Nagasaki, that one-half of the whole adult population are more or less inebriated with saki by nine o'clock every evening! When I state that a great proportion of these drunken people in the capital are armed with two rather sharp swords, and that in this condition they are often ill-natured and quarrelsome, it will be readily seen that the city of Yedo is not a very safe place for foreigners to be about in after nightfall. The remainder of our ride home from Ogee was without any incident worth relating, and I arrived at the house of the English Minister, well pleased with the successful issue of the day's excursion. On various occasions during my stay in Yedo I repeated my visits to Dang-o-zaka, Su-mae-yah, and Ogee, and was thus enabled to add to my collections a very large number of the ornamental trees and shrubs of Japan.  Japanese Heads, showing the mode of dressing the hair 1. Back of head before hair tied up. 2. Second process. 3. Full dress. |