PART I

THE

CUBHOOD OF WAHB

I

E was

born over a score of years ago, away up in the wildest part of the wild

West,

on the head of the Little Piney, above where the Palette Ranch is now. E was

born over a score of years ago, away up in the wildest part of the wild

West,

on the head of the Little Piney, above where the Palette Ranch is now.

His

Mother was just an ordinary Silvertip, living the quiet life that all

Bears

prefer, minding her own business and doing her duty by her family,

asking no

favors of any one excepting to let her alone.

It was

July before she took her remarkable family down the Little Piney to the

Graybull, and showed them what strawberries were, and where to find

them.

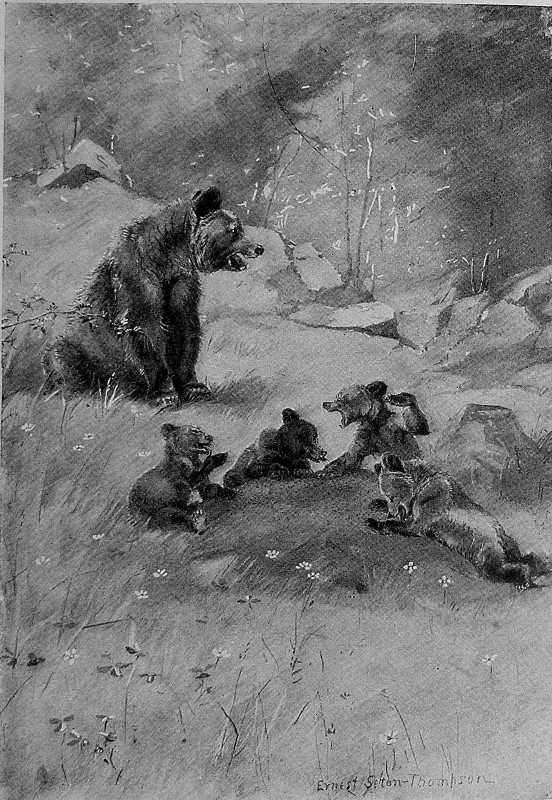

Notwithstanding their Mother's deep conviction, the cubs were not

remarkably

big or bright; yet they were a remarkable family, for there were four

of them,

and it is not often a Grizzly Mother can boast of more than two.

The

woolly-coated little creatures were having a fine time, and reveled in

the

lovely mountain summer and the abundance of good things. Their Mother

turned

over each log and flat stone they came to, and the moment it was lifted

they

all rushed under it like a lot of little pigs to lick up the ants and

grubs

there bidden.

"They all rushed under it like a lot of

little pigs."

It never

once occurred to them that Mammy's strength might fail sometime, and

let the

great rock drop just as they got under it; nor would any one have

thought so

that might have chanced to see that huge arm and that shoulder sliding

about

under the great yellow robe she wore. No, no; that arm could never

fail. The

little ones were quite right. So they bustled and tumbled one another

at each

fresh log in their haste to be first, and squealed little squeals, and

growled

little growls, as if each was a pig, a pup, and a kitten all rolled

into one.

They

were well acquainted with the common little

brown ants that harbor under logs

in the uplands, but now they came forthe first time on one of the hills

of the

great, fat, luscious Wood-ant, and they all crowded around to lick up

those

that ran out. But they soon found that they were licking up more

cactus-prickles and sand than ants, till their Mother said in Grizzly,

"Let me show you how."

She

knocked off the top of the hill, then laid her great paw flat on it for

a few

moments, and as the angry ants swarmed on to it she licked them up with

one

lick, and got a good rich mouthful to crunch, without a grain of sand

or a

cactus-stinger in it. The cubs soon learned. Each put up both his

little brown

paws, so that there was a ring of paws all around the ant-hill, and

there

they sat, like children playing 'hands,' and each licked first the

right and

then the left paw, or one cuffed his brother's ears for licking a paw

that was

not his own, till the ant-hill was cleared out and they were ready for

a

change.

"Like children playing 'Hands.'" Ants are

sour food and made the Bears thirsty, so the old one led down to the

river.

After they had drunk as much as they wanted, and dabbled their feet,

they

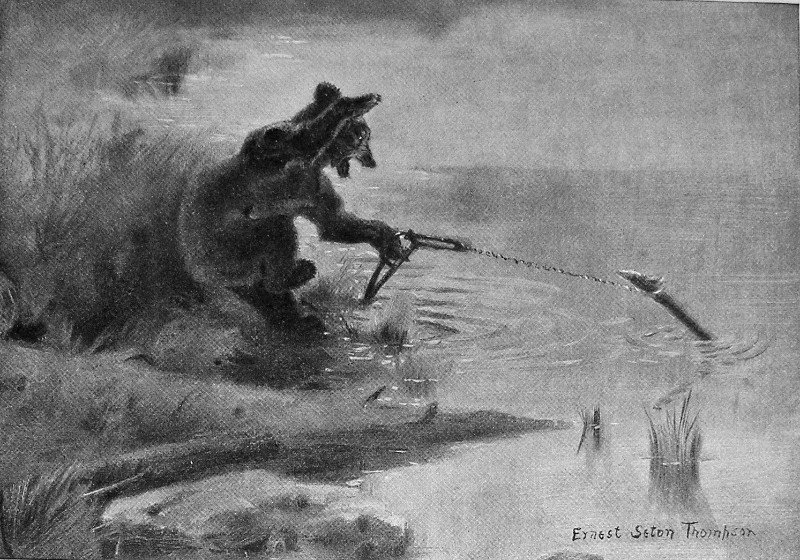

walked down the bank to a pool, where the old one's keen eye caught

sight of a

number of Buffalo-fish basking on the bottom. The water was very low,

mere

pebbly rapids between these deep holes, so Mammy said to the little

ones:

"Now

you all sit there on the bank and learn something new." First she went

to

the lower end of the pool and

stirred up a cloud of mud which hung in

the still water, and sent a long tail floating like a curtain over the

rapids

just below. Then she went quietly round by land, and sprang into the

upper end

of the pool with all the noise she could. The fish had crowded to that

end, but

this sudden attack sent them off in a panic, and they dashed blindly

into the

mud-cloud. Out of fifty fish there is always a good chance of some

being fools,

and half a dozen of these dashed through the darkened water into the

current,

and before they knew it they were struggling over the shingly shallow.

The old

Grizzly jerked them out to the bank, and the little ones rushed noisily

on these

funny, short snakes that could not get away, and gobbled and gorged

till their

little bellies looked like balloons.

They had

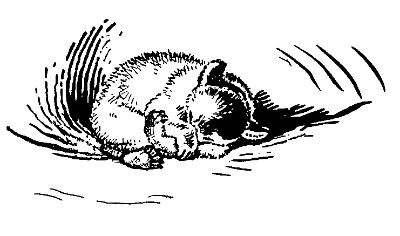

eaten so much now, and the sun was so hot, that all were quite sleepy.

So the

Mother bear led them to a quiet little nook, and as soon as she lay

down,

though they were puffing with beat, they all snuggled around her and

went to

sleep, with their little brown paws curled in, and their little black

noses

tucked into their wool as though it were a very cold day.

After an

hour or two they began to yawn and stretch themselves, except little

Fuzz, the

smallest; she poked out her sharp nose for a moment, then snuggled back

between

her Mother's great arms, for she was a gentle, petted little thing. The

largest, the one afterward known as Wahb, sprawled over on his back and

began

to worry a root that stuck up, grumbling to himself as he chewed it, or

slapped

it with his paw for not staying where he wanted it. Presently Mooney,

the

mischief, began tugging at Frizzle's ears, and got his own well boxed.

They

clenched for a tussle; then, locked in a tight, little grizzly yellow

ball,

they sprawled over and over on the grass, and, before they knew it,

down a

bank, and away out of sight toward the river.

Almost

immediately there was an outcry of yells for help from the little

wrestlers.

There could be no mistaking the real terror in their voices. Some

dreadful

danger was threatening.

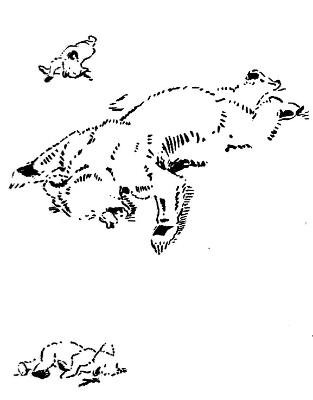

Up

jumped the gentle Mother, changed into a perfect demon, and over the

bank in

time to see a huge Range-bull make a deadly charge at what he doubtless

took

for a yellow dog. In a moment all would have been over with Frizzle,

for he had

missed his footing on the bank; but there was a thumping of heavy feet,

a roar

that startled even the great Bull, and, like a huge bounding ball of

yellow

fur, Mother Grizzly was upon him. Him! the monarch of the herd, the

master of

all these plains, what had he to fear? H e bellowed his deep war-cry,

and charged

to pin the old one to the bank; but as he bent to tear her with his

shining

horns, she dealt him a stunning blow, and before he could recover she

was on

his shoulders, raking the flesh from his ribs with sweep after sweep of

her

terrific claws.

Up

jumped the gentle Mother, changed into a perfect demon, and over the

bank in

time to see a huge Range-bull make a deadly charge at what he doubtless

took

for a yellow dog. In a moment all would have been over with Frizzle,

for he had

missed his footing on the bank; but there was a thumping of heavy feet,

a roar

that startled even the great Bull, and, like a huge bounding ball of

yellow

fur, Mother Grizzly was upon him. Him! the monarch of the herd, the

master of

all these plains, what had he to fear? H e bellowed his deep war-cry,

and charged

to pin the old one to the bank; but as he bent to tear her with his

shining

horns, she dealt him a stunning blow, and before he could recover she

was on

his shoulders, raking the flesh from his ribs with sweep after sweep of

her

terrific claws.

The Bull

roared with rage, and plunged and reared, dragging Mother Grizzly with

him;

then, as he hurled heavily off the slope, she let go to save herself,

and the

Bull rolled down into the river.

This was

a lucky thing for him, for the Grizzly did not want to follow him

there; so he

waded out on the other side, and bellowing with fury and pain, slunk

off to

join the herd to which he belonged.

II

OLD Colonel Pickett,

the cattle king,

was out riding the range. The night

before, he had seen the new moon descending over the white cone of

Pickett's

Peak. OLD Colonel Pickett,

the cattle king,

was out riding the range. The night

before, he had seen the new moon descending over the white cone of

Pickett's

Peak.

"I

saw the last moon over Frank's Peak," said he, "and the luck was

against me for a month; now I reckon it's my turn."

Next

morning his luck began. A letter came from Washington granting

his request that a post-office he established at his ranch, and

contained the

polite inquiry, "What name do you suggest for the new post-office?"

The

Colonel took down his new rifle, a 45-90 repeater. "May as well," he

said; "this is my month"; and he

rode up

the

Graybull

to see how the cattle were doing.

As he

passed under the Rimrock Mountain he heard a far-away roaring as of

Bulls

fighting, but thought nothing of it till he rounded the point and saw

on the

flat below a lot of his cattle pawing the dust and bellowing as they

always do

when they smell the blood of one of their number. He soon saw that the

great

Bull, 'the boss of the bunch,' was covered with blood. His back and

sides were

torn as by a Mountain-lion, and his head was battered as by another

Bull.

"Grizzly,"

growled the Colonel, for he knew the mountains. He quickly noted the

general

direction of the Bull's back trail, then rode toward a high bank that

offered a

view. This was across the gravelly ford of the Graybull, near the mouth

of the

Piney. His horse splashed through the cold water and began jerkily to

climb the

other bank.

As soon

as the rider's head rose above the bank his hand grabbed the rifle, for

there

in full sight were five Grizzly Bears, an old one and four cubs.

"Run

for the woods," growled the Mother Grizzly, for she knew that men

carried

guns. Not that she feared for herself; but the idea of such things

among her

darlings was too horrible to think of. She set off to guide them to the

timber-tangle on the Lower Piney. But an awful, murderous fusillade

began.

Bang! and

Mother Grizzly felt a deadly pang.

Bang! and

Mother Grizzly felt a deadly pang.

Bang! and poor little Fuzz

rolled over

with a scream of pain and lay still.

With a

roar of hate and fury Mother Grizzly turned to attack the enemy.

Bang! and she fell paralyzed

and dying

with a high shoulder shot. And the three little cubs, not knowing what

to do,

ran back to their Mother.

Bang!

bang! and

Mooney and Frizzle sank in

dying agonies beside her, and Wahb, terrified and stupefied, ran in a

circle

about them. Then, hardly knowing why, he turned and dashed into the

timber-tangle, and disappeared as a last bang left

him with a

stinging pain and a useless, broken bind

paw.

THAT is why

the post-office was called Four-Bears. The Colonel seemed pleased with

what he

had done; indeed, he told of it

himself.

But away

up in the woods of Anderson's Peak that night a little lame

Grizzly might have been seen wandering, limping along, leaving a bloody

spot

each time he tried to set down his hind paw; whining and whimpering,

"Mother! Mother! Oh, Mother, where are you?" for he was cold and

hungry, and had such a pain in his foot. But there was no Mother to

come to

him, and he dared not go back where he had left her, so he wandered

aimlessly

about among the pines.

Then he

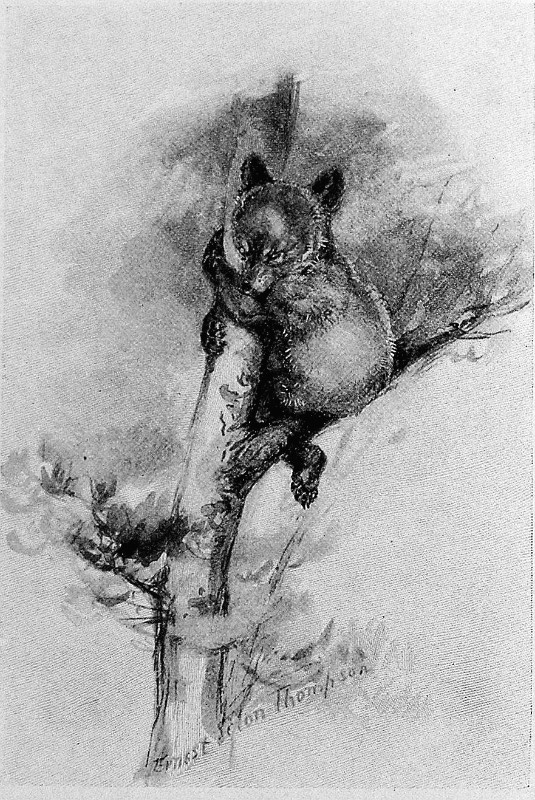

smelled some strange animal smell and heard heavy footsteps; and not

knowing

what else to do, he climbed a tree. Presently a band of great,

long-necked,

slim-legged animals, taller than his Mother, came by under the tree. He

had seen

such once before and had not been afraid of them then, because he had

been with

his Mother. But now he kept very quiet in the tree, and the big

creatures stopped

picking the grass when they were near him, and blowing their noses, ran

out of

sight. Then he

smelled some strange animal smell and heard heavy footsteps; and not

knowing

what else to do, he climbed a tree. Presently a band of great,

long-necked,

slim-legged animals, taller than his Mother, came by under the tree. He

had seen

such once before and had not been afraid of them then, because he had

been with

his Mother. But now he kept very quiet in the tree, and the big

creatures stopped

picking the grass when they were near him, and blowing their noses, ran

out of

sight.

He

stayed in the tree till near morning, and then he was so stiff with cold that he could scarcely get down.

But the warm sun came up, and he felt better as he sought about for

berries and

ants, for he was very hungry. Then he went back to the Piney and put

his

wounded foot in the ice-cold water.

He

wanted to get back to the mountains again, but still he felt he must go

to

where he had left his Mother and brothers.

When the afternoon grew warm,

he went limping down the stream through the timber, and down on the

banks of

the Graybull till he came to the place where yesterday they had had the

fish-feast; and he eagerly crunched the heads and remains that he

found. But

there was an odd and horrid smell on the wind. It frightened him, and

as he

went down to where he last had seen his Mother the smell grew worse. He

peeped

out cautiously at the place, and saw there a lot of Coyotes, tearing at

something. What it was he did not know; but he saw no Mother, and the

smell

that sickened and terrified him was worse than ever, so he quietly

turned back

toward the timber-tangle of the Lower Piney, and nevermore came back to

look

for his lost family. He wanted his Mother as much as ever, but

something told

him it was no use. He

wanted to get back to the mountains again, but still he felt he must go

to

where he had left his Mother and brothers.

When the afternoon grew warm,

he went limping down the stream through the timber, and down on the

banks of

the Graybull till he came to the place where yesterday they had had the

fish-feast; and he eagerly crunched the heads and remains that he

found. But

there was an odd and horrid smell on the wind. It frightened him, and

as he

went down to where he last had seen his Mother the smell grew worse. He

peeped

out cautiously at the place, and saw there a lot of Coyotes, tearing at

something. What it was he did not know; but he saw no Mother, and the

smell

that sickened and terrified him was worse than ever, so he quietly

turned back

toward the timber-tangle of the Lower Piney, and nevermore came back to

look

for his lost family. He wanted his Mother as much as ever, but

something told

him it was no use.

As cold

night came down, he missed her more and more again, and he whimpered as

he

limped along, a miserable, lonely, little, motherless Bear -- not lost

in the

mountains, for he had no home to seek, but so sick and lonely, and with

such a

pain in his foot, and in his stomach a craving for the drink that would

nevermore be his. That night he found a hollow log, and crawling in, he

tried

to dream that his Mother's great, furry arms were around him, and he

snuffled

himself to sleep.

III

AHB had

always been a gloomy little Bear; and the string of misfortunes that

came on

him just as his mind was forming made him more than ever sullen and

morose. It

seemed as though every one were against him. He tried to keep out of

sight in

the upper woods of the Piney, seeking his food by day and resting at

night in

the hollow log. But one evening he found it occupied by a Porcupine as

big as

himself and as bad as a cactus-bush. Wahb could do nothing with him. He

had to

give up the log and seek another nest. AHB had

always been a gloomy little Bear; and the string of misfortunes that

came on

him just as his mind was forming made him more than ever sullen and

morose. It

seemed as though every one were against him. He tried to keep out of

sight in

the upper woods of the Piney, seeking his food by day and resting at

night in

the hollow log. But one evening he found it occupied by a Porcupine as

big as

himself and as bad as a cactus-bush. Wahb could do nothing with him. He

had to

give up the log and seek another nest.

One day

he went down on the Graybull flat to dig some roots that his Mother had

taught

him were good. But before he had well begun, a grayish-looking animal

came out

of a hole in the ground and rushed at him, hissing and growling. Wahb

did not

know it was a Badger, but he saw it was a fierce animal as big as

himself. He

was sick, and lame too, so he limped away and never stopped till he was

on a

ridge in the next caņon. Here a Coyote saw him, and came

bounding after him, calling

at the same time to another to come and join the fun. Wahb was near a

tree, so he

scrambled up to the branches. The Coyotes came bounding and yelping

below, but

their noses told them that this was a young Grizzly they had chased,

and they

soon decided that a young Grizzly in a tree means a Mother Grizzly not

far

away, and they had better let him alone.

After

they had sneaked off Wahb came down and returned to the Piney. There

was better

feeding on the Graybull, but every one seemed against him there now

that his

loving guardian was gone, while on the Piney he had peace at least

sometimes,

and there were plenty of trees that he could climb when an enemy came. After

they had sneaked off Wahb came down and returned to the Piney. There

was better

feeding on the Graybull, but every one seemed against him there now

that his

loving guardian was gone, while on the Piney he had peace at least

sometimes,

and there were plenty of trees that he could climb when an enemy came.

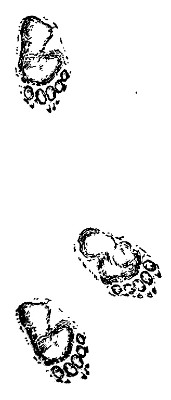

His

broken foot was a long time in healing; indeed, it never got quite

well. The

wound healed and the soreness wore off, but it left a stiffness that

gave him a

slight limp, and the sole-balls grew together quite unlike those of the

other

foot. It particularly annoyed him when he had to climb a tree or run

fast from

his enemies; and of them he found no end, though never once did a

friend cross

his path. When he lost his Mother he lost his best and only friend. She

would

have taught him much that he had to learn by bitter experience, and

would have

saved him from most of the ills that befell him in his cubhood -- ills

so many

and so dire that but for his native sturdiness he never could have

passed

through alive.

The

piņons bore plentifully that year, and the winds began to shower

down the ripe,

rich nuts. Life was becoming a little easier for Wahb. He was gaining

in health

and strength, and the creatures he daily met now let him alone. But as

he

feasted on the piņons one morning after a gale, a great

Blackbear came marching

down the bill. 'No one meets a friend in the woods,' was a byword that

Wahb had

learned already. He swung up the nearest tree. At first the Blackbear

was

scared, for he smelled the smell of Grizzly; but when he saw it was

only a cub,

he took courage and came growling at Wahb. He could climb as well as

the little

Grizzly, or better, and high as Wahb went, the Blackbear followed, and

when

Wahb got out on the smallest and highest twig that would carry him, the

Blackbear cruelly shook him off, so that he was thrown to the ground,

bruised

and shaken and half-stunned. He limped away moaning, and the only thing

that

kept the Blackbear from following him up and perhaps killing him was

the fear

that the old Grizzly might be about. So Wahb was driven away down the

creek

from all the good piņon woods.

There

was not much food on the Graybull now. The berries were nearly all

gone; there

were no fish or ants to get, and Wahb, hurt, lonely, and miserable,

wandered on

and on, till he was away down toward the Meteetsee.

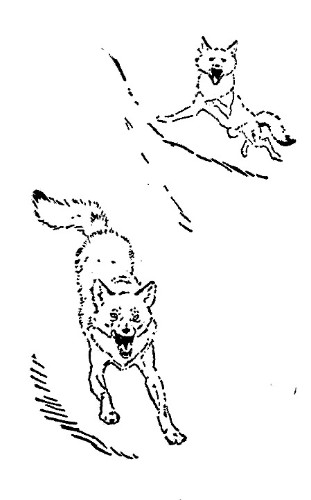

A Coyote

came bounding and barking through the sage-brush after him. Wahb tried

to run,

but it was no use; the Coyote was soon up with him. Then with a sudden

rush of

desperate courage Wahb turned and charged his foe. The astonished

Coyote gave a

scared yowl or two, and fled with his tail between his legs. Thus Wahb

learned

that war is the price of peace.

But the

forage was poor here; there were too many cattle; and Wahb was making

for a

far-away piņon woods in the Meteetsee Caņon when he saw a

man, just like the

one he had seen on that day of sorrow. At the same moment he heard a bang, and some sage-brush

rattled and fell just over his back. All the dreadful smells and

dangers of

that day came back to his memory, and Wahb ran as he never had run

before.

He soon

got into a gully and followed it into the caņon. An opening

between two cliffs

seemed to offer shelter, but as he ran toward it a Range-cow came

trotting

between, shaking her head at him and snorting threats against his life.

He

leaped aside upon a long log that led up a bank, but at once a savage

Bobcat

appeared on the other end and warned him to go back. It was no time to

quarrel.

Bitterly Wahb felt that the world was full of enemies. But he turned

and

scrambled up a rocky bank into the piņon woods that border the

benches of the

Meteetsee.

The Pine

Squirrels seemed to resent his coming, and barked furiously. They were

thinking

about their piņon-nuts. They knew that this Bear was coming to

steal their

provisions, and they followed him overhead to scold and abuse him, with

such an

outcry that an enemy might have followed him by their noise, which was

exactly

what they intended.

The Pine

Squirrels seemed to resent his coming, and barked furiously. They were

thinking

about their piņon-nuts. They knew that this Bear was coming to

steal their

provisions, and they followed him overhead to scold and abuse him, with

such an

outcry that an enemy might have followed him by their noise, which was

exactly

what they intended.

There

was no one following, but it made Wahb uneasy and nervous. So he kept

on till

he reached the timber line, where both food and foes were scarce, and

here on

the edge of the Mountain-sheep land at last he got a chance to rest.

IV

AHB

never was sweet-tempered like his baby

sister, and the persecutions by his numerous foes were making him more

and more

sour. Why could not they let him alone in his misery? Why was every one

against

him? If only he had his Mother back! If he could only have killed that

Blackbear that had driven him from his woods! It did not occur to him

that some

day he himself would be big. And that spiteful

Bobcat, that took advantage

of him; and the man that had tried to kill him. He did not forget any

of them,

and he hated them all. AHB

never was sweet-tempered like his baby

sister, and the persecutions by his numerous foes were making him more

and more

sour. Why could not they let him alone in his misery? Why was every one

against

him? If only he had his Mother back! If he could only have killed that

Blackbear that had driven him from his woods! It did not occur to him

that some

day he himself would be big. And that spiteful

Bobcat, that took advantage

of him; and the man that had tried to kill him. He did not forget any

of them,

and he hated them all.

Wahb

found his new range fairly good, because it was a good nut year. He

learned

just what the Squirrels feared he would, for his nose directed him to

the

little granaries where they had stored up great quantities of nuts for

winter's

use. It was hard on the Squirrels, but it was good luck for Wahb, for

the nuts

were delicious food. And when the days shortened and the nights began

to be

frosty, he had grown fat and well-favored.

He

traveled over all parts of the caņon now, living mostly in the higher

woods, but coming down at times to forage almost as far as the river.

One night

as he wandered by the deep water a peculiar smell reached his nose. It

was

quite pleasant, so he followed it up to the water's edge. It seemed to

come

from a sunken log. As he reached over toward this, there was a sudden clank, and one of his paws

was caught

in a strong, steel Beaver-trap.

"Whab yelled and jerked back."  Wahb

yelled and jerked back with all his strength, and tore up the stake

that held

the trap. He tried to shake it off, then ran away through the bushes

trailing

it. He tore at it with his teeth; but there it bung, quiet, cold,

strong, and

immovable. Every little while he tore at it with his

teeth and

claws, or beat it against the ground. He buried it in the earth, then

climbed a

low tree, hoping to leave it behind; but still it clung, biting into

his flesh.

He made for his own woods, and sat down to try to puzzle it out. He did

not

know what it was, but his little green-brown eyes glared with a mixture

of pain,

fright, and fury as he tried to understand his new enemy.

Wahb

yelled and jerked back with all his strength, and tore up the stake

that held

the trap. He tried to shake it off, then ran away through the bushes

trailing

it. He tore at it with his teeth; but there it bung, quiet, cold,

strong, and

immovable. Every little while he tore at it with his

teeth and

claws, or beat it against the ground. He buried it in the earth, then

climbed a

low tree, hoping to leave it behind; but still it clung, biting into

his flesh.

He made for his own woods, and sat down to try to puzzle it out. He did

not

know what it was, but his little green-brown eyes glared with a mixture

of pain,

fright, and fury as he tried to understand his new enemy.

He lay

down under the bushes, and, intent on deliberately crushing the thing,

he held

it down with one paw while he tightened his teeth on the other end, and

bearing

down as it slid away, the trap jaws opened and the foot was free. It

was mere

chance, of course, that led him to squeeze both springs at once. He did

not

understand it, but he did not forget it, and he got these not very

clear ideas:

'There is a dreadful

little enemy that hides by the water

and waits for one. It has an odd smell. It bites one's paws and is too

hard for

one to bite. But it can be got off by hard squeezing.'

For a week or

more the

little Grizzly had another sore paw, but it was not very bad if he did

not do

any climbing.

It was

now the season when the Elk were bugling on the mountains. Wahb heard

them all

night, and once or twice had to climb to get away from one of the

big-antlered

Bulls. It was also the season when the trappers were coming into the

mountains,

and the Wild Geese were honking overhead. There were several quite new

smells

in the woods, too. Wahb followed one of these up, and it led to a place

where

were some small logs piled together; then, mixed with the smell that

had drawn

him, was one that he hated -- he remembered it from the time when he

had lost

his Mother. He sniffed about carefully, for it was not very strong, and

learned

that this hateful smell was on a log in front, and the sweet smell that

made

his mouth water was under some brush behind. So he went around, pulled

away the

brush till he got the prize, a piece of meat, and as he grabbed it, the

log in

front went down with a heavy chock.

It made

Wahb jump; but he got away all right with the meat and some new ideas,

and with

one old idea made stronger, and that was, 'When that hateful

smell

is around it always means trouble.'

As the

weather grew colder, Wahb became very sleepy; he slept all day when it

was

frosty. He had not any fixed place to sleep in; he knew a number of dry

ledges

for sunny weather, and one or two sheltered nooks for stormy days. He

had a

very comfortable nest under a root, and one day, as it began to blow

and snow,

he crawled into this and curled up to sleep. The storm howled without.

The snow

fell deeper and deeper. It draped the pine-trees till they bowed, then

shook

themselves clear to be draped anew. It drifted over the mountains and

poured

down the funnel-like ravines, blowing off the peaks and ridges, and

filling up

the hollows level with their rims. It piled up over Wahb's den,

shutting out

the cold of the winter, shutting out itself: and Wahb slept and slept.

V

E slept

all winter without waking, for such is the way of Bears, and yet when

spring

came and aroused him, he knew that he had been asleep a long time. He

was not

much changed -- he had grown in height, and yet was but little thinner.

He was

now very hungry, and forcing his way through the deep drift that still

lay over

his den, he set out to look for food. E slept

all winter without waking, for such is the way of Bears, and yet when

spring

came and aroused him, he knew that he had been asleep a long time. He

was not

much changed -- he had grown in height, and yet was but little thinner.

He was

now very hungry, and forcing his way through the deep drift that still

lay over

his den, he set out to look for food.

There

were no piņon-nuts to get, and no

berries or ants; but Wahb's nose led

him away

up the caņon to the body of a winter-killed Elk, where he had a

fine feast, and

then buried the rest for future use. There

were no piņon-nuts to get, and no

berries or ants; but Wahb's nose led

him away

up the caņon to the body of a winter-killed Elk, where he had a

fine feast, and

then buried the rest for future use.

Day

after day he came back till he had finished it. Food was very scarce

for a

couple of months, and after the Elk was eaten, Wahb lost all the fat he

had

when he awoke. One day he climbed over the Divide into the Warhouse

Valley. It

was warm and sunny there, vegetation was well advanced, and he found

good

forage. He wandered down toward the thick timber, and soon smelled the

smell of

another Grizzly. This grew stronger and led him to a single tree by a

Bear-trail. Wahb reared up on his hind feet to smell this tree. It was

strong

of Bear, and was plastered with mud and Grizzly hair far higher than he

could

reach; and Wahb knew that it must have been a very large Bear that had

rubbed

himself there. He felt uneasy. He used to long to meet one of his own

kind, yet

now that there was a chance of it he was filled with dread.

No one

had shown him anything but hatred in his lonely, unprotected life, and

he could

not tell what this older Bear might do. As he stood in doubt, he caught

sight

of the old Grizzly himself slouching along a hillside, stopping from

time to

time to dig up the quamash-roots and wild turnips.

He was a

monster. Wahb instinctively distrusted him, and sneaked away through

the woods

and up a rocky bluff where he could watch.

Then the

big fellow came on Wahb's track and rumbled a deep growl of anger; he

followed

the trail to the tree, and rearing up, he tore the bark with his claws,

far

above where Wahb had reached. Then he strode rapidly along Wahb's

trail. But

the cub had seen enough. He fled back over the Divide into the

Meteetsee Caņon,

and realized in his dim, bearish way that he was at peace there because

the

Bear-forage was so poor.

As the

summer came on, his coat was shed. His skin got very itchy, and he

found

pleasure in rolling in the mud and scraping his back against some

convenient

tree. He never climbed now: his claws were too long, and his arms,

though

growing big and strong, were losing that suppleness of wrist that makes

cub

Grizzlies and all Blackbears great climbers. He now dropped naturally

into the

Bear habit of seeing how high he could reach with his nose on the

rubbing-post,

whenever he was near one.

He may

not have noticed it, yet each time he came to a post, after a week or

two away,

he could reach higher, for Wahb was growing fast and coming into his

strength. He may

not have noticed it, yet each time he came to a post, after a week or

two away,

he could reach higher, for Wahb was growing fast and coming into his

strength.

Sometimes

he was at one end of the country that he felt was his, and sometimes at

another,

but he had frequent use for the rubbing-tree, and thus it was that his

range

was mapped out by posts with his own mark on them.

One day

late in summer he sighted a stranger on his land, a glossy Blackbear,

and he

felt furious against the interloper. As the Blackbear came nearer Wahb

noticed

the tan-red face, the white spot on his breast, and then the bit out of

his

ear, and last of all the wind brought a whiff. There could be no

further doubt;

it was the very smell: this was the black coward that had chased him

down the

Piney long ago. But how he had shrunken! Before, he had looked like a

giant;

now Wahb felt he could crush him with one paw. Revenge is sweet, Wahb

felt,

though he did not exactly say it, and he went for that red-nosed Bear.

But the

Black one went up a small tree like a Squirrel. Wahb tried to follow as

the

other once followed him, but somehow he could not. He did not seem to

know how

to take hold now, and after a while he gave it up and went away,

although the

Blackbear brought him back more than once by coughing in derision.

Later on

that day, when the Grizzly passed again, the red-nosed one had gone.

As the

summer waned, the upper forage-grounds began to give out, and Wahb

ventured

down to the Lower Meteetsee one night As the

summer waned, the upper forage-grounds began to give out, and Wahb

ventured

down to the Lower Meteetsee one night

The

Coyote was caught in a trap. Wahb hated the smell of the iron, so he

went to

the other side of the carcass, where it was not so strong, and had

eaten but

little before clank, and

his

foot was caught in a Wolf-trap that he had not seen.

But he

remembered that he had once before been caught and had escaped by

squeezing the

trap. He set a hind foot on each spring and pressed till the trap

opened and

released his paw. About the carcass was the smell that he knew stood

for man,

so he left it and wandered down-stream; but more and more often he got

whiffs

of that horrible odor, so he turned and went back to his quiet

piņon benches.

Click the book image to

turn to

the next Chapter. |