|

SILVERHORNS

THE railway station of Bathurst,

New Brunswick,

did not

look particularly merry at two o'clock of a late September morning.

There

was an easterly haar driving in from the Baie

des Chaleurs and the

darkness was so saturated with chilly moisture that an honest downpour

of

rain would have been a relief. Two or three depressed and somnolent

travellers

yawned in the waiting-room, which smelled horribly of smoky lamps. The

telegraph

instrument in the ticket-office clicked spasmodically for a minute, and

then

relapsed into a gloomy silence. The imperturbable station-master was

tipped

back against the wall in a wooden armchair, with his feet on the table,

and

his mind sunk in an old Christmas number of The

Cowboy Magazine. The

express-agent, in the baggage-room, was going over his last week's

way-bills

and accounts by the light of a lantern, trying to locate an error, and

sighing

profanely to himself as he failed to find it. A wooden trunk tied with

rope,

a couple of dingy canvas bags, a long box marked "Fresh Fish! Rush!"

and

two large leather portmanteaus with brass fittings were piled on the

luggage-truck at the far end of the platform; and beside the door of

the

waiting-room, sheltered by the overhanging eaves, was a neat travelling

bag,

with a gun-case and a rod-case leaning against the wall. The wet rails

glittered

dimly northward and southward away into the night. A few blurred lights

glimmered

from the village across the bridge.

Dudley Hemenway had observed all these features of

the

landscape with silent dissatisfaction, as he smoked steadily up and

down

the platform, waiting for the Maritime Express. It is usually

irritating

to arrive at the station on time for a train on the Intercolonial

Railway.

The arrangement is seldom mutual; and sometimes yesterday's train does

not

come along until to-morrow afternoon. Moreover, Hemenway was inwardly

discontented with the fact that he was coming out of the woods instead

of

going in. "Coming out" always made him a little unhappy, whether his

expedition

had been successful or not. He did not like the thought that it was all

over;

and he had the very bad habit, at such times, of looking ahead and

computing

the slowly lessening number of chances that were left to him.

"Sixty odd years – I may live to be that

old and

keep

my shooting sight," he said to himself. "That would give me a couple of

dozen

more camping trips. It's a short allowance. I wonder if any of them

will

be more lucky than this one. This makes the seventh year I've tried to

get

a moose; and the odd trick has gone against me every time."

He tossed away the end of his cigar, which made a

little

trail of sparks as it rolled along the sopping platform, and turned to

look

in through the window of the ticket-office. Something in the agent's

attitude

of literary absorption aggravated him. He went round to the door and

opened

it.

"Don't you know or care when this train is

coming?"

"Nope," said the man placidly.

"Well, when? What's the matter with her? When is

she

due?"

"Doo twenty minits ago," said the man. "Forty

minits

late down to Noocastle. Git here quarter to three, ef nothin' more

happens."

"But what has happened already? What's wrong with

the

beastly old road, anyhow?"

"Freight-car skipped the track," said the man "up

to

Charlo. Everythin' hung up an' kinder goin' slow till they git the line

clear.

Dunno nothin' more."

With this conclusive statement the agent seemed to

disclaim

all responsibility for the future of impatient travellers, and dropped

his

mind back into the magazine again. Hemenway lit another cigar and went

into

the baggage-room to smoke with the expressman. It was nearly three

o'clock

when they heard the far-off Shriek of the whistle sounding up from the

south;

then, after an interval, the puffing of the engine on the up-grade;

then

the faint ringing of the rails, the increasing clatter of the train,

and

the blazing headlight of the locomotive swept slowly through the

darkness,

past the platform. The engineer was leaning on one arm, with his head

out

of the cab-window, and as he passed he nodded and waved his hand to

Hemenway.

The conductor also nodded and hurried into the ticket-office, where the

tick-tack

of a conversation by telegraph was soon under way. The black porter of

the

Pullman ear was looking out from the vestibule, and when he saw

Hemenway

his sleepy face broadened into a grin reminiscent of many generous

tips.

"Howdy, Mr. Hennigray," he cried; "glad to see yo'

ag'in,

sah! I got yo' section alright, sah! Lemme take yo' things, sah! Train

gwine

to stop hy'eh fo' some time yet, I reckon."

"Well, Charles," said Hemenway, "you take my

things and

put them in file car. Careful with that gun now! The Lord only knows

how

much time fills train's going to lose. I'm going ahead to see the

engineer."

Angus McLeod was a grizzle-bearded Scotchman who

had

run a locomotive on the Intercolonial ever since the road was cut

through

the woods from New Brunswick to Quebec. Everyone who travelled often on

that

line knew him, and all who knew him well enough to get below his rough

crust,

liked him for his big heart.

"Hallo, McLeod," said Hemenway as he came up

through

the darkness, "is that you?"

"It's nane else," answered the engineer

as he

stepped down from his cab and shook hands warmly. "Hoo are ye, Dud, an'

whaur

hae ye been murderin' the innocent beasties noo? Hae ye killt yer moose

yet?

Ye've been chasin' him these mony years."

"Not much murdering," replied Hemenway. "I had a

queer

trip this time – away up the Nepissiguit, with old

McDonald. You know

him,

don't you?"

"Fine do I ken Rob McDonald, an' a guid mon he is.

Hoo

was it that ye couldna slaughter stacks o' moose wi' him to help ye?

Did

ye see nane at all?"

"Plenty, and one with the biggest horns in the

world!

But that's a long story, and there's no time to tell it now."

"Time to burrrn, Dud, nae fear o' it! 'Twill be an

hour

afore the line's clear to Charlo an' they lat us oot o' this. Come awa'

up

into the cab, mon, an' tell us yer tale.' Tis couthy an' warm in the

cab,

an' I'm willin' to leesten to yer bluidy advaintures."

So the two men clambered up into the engineer's

seat.

Hemenway gave McLeod his longest and strongest cigar, and filled his

own

briarwood pipe. The rain was now pattering gently on the roof of the

cab.

The engine hissed and sizzled patiently in the darkness. The fragrant

smoke

curled steadily from the glowing tip of the cigar; but the pipe went

out

half a dozen times while Hemenway was telling the story of Silverhorns.

"We went up the river to the big rock, just below

Indian

Falls. There we made our main camp, intending to hunt on Forty-two Mile

Brook.

There's quite a snarl of ponds and bogs at the head of it, and some

burned

hills over to the west, and it's very good moose country.

"But some other party had been there before us,

and we

saw nothing on the ponds, except two cow moose and a calf. Coming out

the

next morning we got a fine deer on the old wood road

– a beautiful

head.

But I have plenty of deer-heads already."

"Bonny creature!" said McLeod. "An' what did ye do

wi'

it, when ye had murdered it?"

"Ate it, of course. I gave the head to Billy

Boucher,

the cook. He said he could get ten dollars for it. The next evening we

went

to one of the ponds again, and Injun Pete tried to 'call' a moose for

me.

But it was no good. McDonald was disgusted with Pete's calling; said it

sounded

like the bray of a wild ass of the wilderness. So the next day we gave

up

calling and travelled the woods over toward the burned hills.

"In the afternoon McDonald found an enormous

moose-track;

he thought it looked like a bull's track, though he wasn't quite

positive.

But then, you know, a Scotchman never likes to commit himself, except

about

theology or politics."

"Humph!" grunted McLeod in the darkness, showing

that

the stroke had counted.

"Well, we went on, following that track through

the woods,

for an hour or two. It was a terrible country, I tell you: tamarack

swamps,

and spruce thickets, and windfalls, and all kinds of misery. Presently

we

came out on a bare rock on the burned hillside, and there, across a

ravine,

we could see the animal lying down, just below the trunk of a big dead

spruce

that had fallen. The beast's head and ne& were hidden by some

bushes,

but the foreshoulder and side were in clear view, about two hundred and

fifty

yards away. McDonald seemed to be inclined to think that it was a bull

and

that I ought to shoot. So I shot, and knocked splinters out of the

spruce

log. We could see them fly. The animal got up quickly, and looked at us

for

a moment, shaking her long ears; then the huge, unmitigated cow

vamoosed

into the brush. McDonald remarked that it was 'a varra fortunate shot,

almaist

providaintial!' And so it was; for if it had gone six inches lower, and

the

news had gotten out at Bathurst, it would have cost me a fine of two

hundred

dollars."

"Ye did weel, Dud," puffed McLeod; "varra weel

indeed

for the coo!"

"After that," continued Hemenway, "of course my

nerve

was a little shaken, and we went back to the main camp on the river, to

rest

over Sunday. That was all right, wasn't it, Mac?"

"Aye?" replied McLeod, who was a strict member of

the

Presbyterian church at Moncton. "That was surely a varra safe thing to

do.

Even a hunter, I'm thinkin', wouldna like to be breakin' twa

commandmerits

in the ane day – the foorth and the saxth!"

"Perhaps not. It's enough to break one, as you do

once

a fortnight when you run your train into Riviére

du Loup Sunday

morning. How's that, you old Calvinist?"

"Dudley, ma son," said the engineer, "dinna airgue

a

point that ye canna understond. There's guid an' suffeecient reasons

for

the train. But ye'll ne'er be claimin' that moose-huntin' is a wark o'

neecessity

or mairey?"

"No, no, of course not; but then, you see, barring

Sundays,

we felt that it was necessary to do all we could to get a moose, just

for

the sake of our reputations. Billy, the cook, was particularly strong

about

it. He said that an old woman in Bathurst, a kind of fortune-teller,

had

told him that he was going to have 'la

bonne chance' on this trip.

He wanted to try his own mouth at 'calling.' He had never really done

it

before. But he had been practising all winter in imitation of a tame

cow

moose that Johnny Moreau had, and he thought he could make the sound 'b'en

bon.' So he got the

birch-bark horn and gave us a sample of his

skill. McDonald told me privately that it was 'nae sa bad; a deal

better

than Pete's feckless bellow.' We agreed to leave the Indian to keep the

camp

(after locking up the whiskey-flask in my bag), and take Billy with us

on

Monday to 'call' at Hogan's Pond.

"It's a small bit of water, about three-quarters

of a

mile long and four hundred yards across, and four miles back from the

river.

There is no trail to it, but a blazed line runs part of the way, and

for

the rest you follow up the little brook that runs out of the pond. We

stuck

up our shelter in a hollow on the brook, half a mile below the pond, so

that

the smoke of our fire would not drift over the hunting-ground, and

waited

till five o'clock in the afternoon. Then we went up to the pond, and

took

our position in a clump of birch-trees on the edge of the open meadow

that

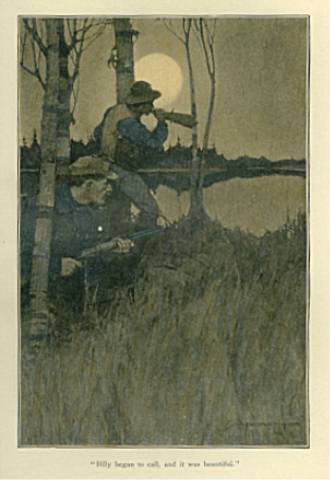

runs round the east shore. Just at dark Billy began to call, and it was

beautiful. You know how it goes. Three short grunts, and then a long

ooooo-aaaa-ooooh, winding up with another grunt! It sounded lonelier

than

a love-sick hippopotamus on the house-top. It rolled and echoed over

the

hills as if it would wake the dead.

"There was a fine moon shining, nearly full, and a

few

clouds floating by. Billy called, and called, and called again. The air

grew

colder and colder; light frost on the meadow-grass; our teeth were

chattering,

fingers numb.

"Then we heard a bull give a short bawl, away off

to

the southward. Presently we could hear his horus knock against the

trees,

far up on the hill. McDonald whispered, 'He's comin',' and Billy gave

another

call.

Billy

began to call, and

it was beautiful.

"But it was another bull that answered, back of

the north

end of the pond, and pretty soon we could hear him rapping along

through

the woods. Then everything was still. 'Call agen,' says McDonald, and

Billy

called again.

"This time the bawl came from another bull, on top

of

the western hill, straight across the pond. It seemed to start up the

other

two bulls, and we could hear all three of them thrashing along, as fast

as

they could come, towards the pond. 'Call agen, a wee one,' says

McDonald,

trembling with joy. And Billy called a little, seducing call, with two

grunts

at the end.

"Well, sir, at that, a cow and a calf came rushing

down

through the brush not two hundred yards away from us, and the three

bulls

went splash into the water, one at the south end, one at the north end,

and

one on the west shore. 'Lord,' whispers McDonald, 'it's a

meenadgerie!'"

"Dud," said the engineer, getting down to open the

furnace

door a crack, "this is mair than murder ye're comin' at; it's a

buitchery – or else it's juist a pack o' lees."

"I give you my word," said Hemenway, "it's all

true as

the catechism. But let me go on. The cow and the calf only stayed in

the

water a few minutes, and then ran back through the woods. But the three

bulls

went sloshing around in the pond as if they were looking for something.

We

could hear them, but we could not see any of them, for the sky had

clouded

up, and they kept far away from us. Billy tried another short call, but

they

did not come any nearer. McDonald whispered that he thought the one in

the

south end might be the biggest, and he might be feeding, and the two

others

might be young bulls, and they might be keeping away because they were

afraid

of the big one. This seemed reasonable; and I said that I was going to

crawl

around the meadow to the south end. 'Keep near a tree,' says Mac; and I

started.

"There was a deep trail, worn by animals~ through

the

high grass; and in this I crept along on my hands and knees. It was

very

wet and muddy. My boots were full of cold water~ After ten minutes I

came

to a little point running out into the pond, and one young birch

growing

on it. Under this I crawled, and rising up on my knees looked over the

top

of the grass and bushes.

"There, in a shallow bay, standing knee-deep in

the water,

and rooting up the lily-stems with his long, pendulous nose, was the

biggest

and blackest bull moose in the world. As he pulled the roots from the

mud

and tossed up his dripping head I could see his horns

– four and a

half

feet across, if they were an inch, and the palms shining like tea-trays

in

the moonlight. I tell you, old Silverhorns was the most beautiful

monster

I ever saw.

"But he was too far away to shoot by that dim

light,

so I left my birch-tree and crawled along toward the edge of the bay. A

breath

of wind must have blown across me to him, for he lifted his head,

sniffed,

grunted, came out of the water, and began to trot slowly along the

trail

which led past me. I knelt on one knee and tried to take aim. A black

cloud

came over the moon. I couldn't see either of the sights on the gun. But

when

the bull came opposite to me, about fifty yards off, I blazed away at a

venture.

"He reared straight up on his hind legs

– it

looked as if he rose fifty feet in the air – wheeled,

and went

walloping

along the trail, around the south end of the pond. In a minute he was

lost

in the woods. Good-by, Silverhorns!"

"Ye tell it weel," said McLeod, reaching out for a

fresh

cigar, "legs! Ah door Sir Walter himsel' couldna impruve upon it. An,

sac

thor's the way ye didna murder puir Seelverhorrns? It's a tale I'm

joyfu'

to be hearin'."

"Wait a bit," Hemenway answered. "That's not the

end,

by a long shot. There's worse to follow. The next morning we returned

to

the pond at daybreak, for McDonald thought I might have wounded the

moose.

We searched the bushes and the woods when he went out very carefully,

looking

for drops of blood on his trail."

"Bluid!" groaned the engineer. "Hech, mon, wouldna

that

come nigh to mak' ye greet, to find the beast's red bluid splashed ower

the

leaves, and think o' him staggerin' on thro' the forest, drippin' the

heart

oot o' him wi' every step?"

"But we didn't find any blood, you old

sentimentalist.

That shot in the dark was a clear miss. We followed the trail by broken

bushes

and footprints, for half a mile, and then came back to the pond and

turned

to go down through the edge of the woods to the camp.

"It was just after sunrise. I was walking a few

yards

ahead, McDonald next, and Billy last. Suddenly he looked around to the

left,

gave a Low whistle and dropped to the ground, pointing northward. Away

at.

the head of the pond, beyond the glitter of the sun on the water, the

big

blackness of Silverhorns' head and body was pushing through the bushes,

dripping

with dew.

"Each of us flopped down behind the nearest shrub

as

if we had been playing squat-tag. Billy had the birch-bark horn with

him,

and he gave a low, short call. Silverhorns heard it, turned, and came

parading

slowly down the western shore, now on the sand-beach, now splashing

through

the shallow water. We could see every motion and hear every sound. He

marched

along as if he owned the earth, swinging his huge head from side to

side

and grunting at each step.

"You see, we were just in the edge of

the woods,

strung along the south end of the pond, Billy nearest the west shore,

where

the moose was walking, McDonald next, and I last, perhaps fifteen yards

farther

to the east. It was a fool arrangement, but we had no time to think

about

it. McDonald whispered that I should wait until the moose came close to

us

and stopped.

"So I waited. I could see him swagger along the

sand

and step out around the fallen logs. The nearer he came the bigger his

horns

looked; each palm was like an enormous silver fish-fork with twenty

prongs.

Then he went out of my sight for a minute as he passed around a little

bay

in the southwest corner, getting nearer and nearer to Billy. But I

could

still hear his steps distinctly – slosh, slosh,

slosh – thud, thud,

thud

(the grunting had stopped) – closer came the sound,

until it was

directly

behind the dense green branches of a fallen balsam-tree, not twenty

feet

away from Billy. Then suddenly the noise ceased. I could hear my own

heart

pounding at my ribs, but nothing else. And of Silverhorns not hair nor

hide

was visible. It looked as if he must be a Boojum, and had the power to

'Softly

and silently vanish away.'

"Billy and Mac were beckoning to me fiercely and

pointing

to the green balsam-top. I gripped my rifle and started to creep toward

them.

A little twig, about as thick as the tip of a fishing-rod, cracked

under

my knee. There was a terrible crash behind the balsam, a plunging

through

the underbrush and a rattling among the branches, a lumbering gallop up

the

hill through the forest, and Silverhorns was gone into the invisible.

"He had stopped behind the tree because he smelled

the

grease on Billy's boots. As he stood there, hesitating, Billy and Mac

could

see his shoulder and his side through a gap in the branches

– a

dead-easy

shot. But so far as I was concerned, he might as well have been in

Alaska.

I told you that the way we had placed ourselves was a fool arrangement.

But

McDonald would not say anything about it, except to express his

conviction

that it was not predestinated

we should get that moose."

"Ah didna ken auld Rob had sac much theology aboot

him,"

commented McLeod. "But noo I'm thlnkin' ye went back to yer main camp,

an'

lat puir Seelverhorrns live oot his life?"

"Not much, did we! For now we knew that

he wasn't

badly frightened by the adventure of the night before, and that we

might

get another chance at him. In the afternoon it began to rain; and it

poured

for forty-eight hours. We cowered in our shelter before a smoky fire,

and

lived on short rations of crackers and dried prunes –

it was a hungry

time."

"But wasna there slathers o' food at the main

camp? Ony

rule wad ken eneugh to gae doon to the river an' tak' a guid fill-up."

"But that wasn't what we wanted. It was

Silverhorns.

Billy and I made McDonald stay, and Thursday afternoon, when the clouds

broke

away, we went back to the pond to have a last try at turning our luck.

"This time we took our positions with great care,

among

some small spruces on a point that ran out from the southern meadow. I

was

farthest to the west; McDonald (who had also brought his gun) was next;

Billy,

with the horn, was farthest away from the point where he thought the

moose

would come out. So Billy began to call, very beautifully. The long

echoes

went bellowing over the hills. The afternoon was still and the setting

sun

shone through a light mist, like a ball of red gold.

"Fifteen minutes after sundown Silverhorns gave a

loud

bawl from the western ridge and came crashing down the hill. He cleared

the

bushes two or three hundred yards to our left with a leap, rushed into

the

pond, and came wading around the south shore toward us. The bank here

was

rather high, perhaps four feet above the water, and the mud below it

was

deep, so that the moose sank in to his knees. I give you my word, as he

came

along there was nothing visible to Mac and me except his ears and his

horns.

Everything else was hidden below the bank.

"There were we behind our little spruce-trees. And

there

was Silverhorns, standing still now, right in front of us. And all that

Mac

and I could see were those big ears and those magnificent antlers,

appearing

and disappearing as he lifted and lowered his head. It was a fearful

situation.

And there was Billy, with his birch-bark hooter, forty yards below

us –

he could see the moose perfectly.

"I looked at Mac, and he looked at me. He

whispered something

about predestination. Then Billy lifted his horn and made ready to give

a

little soft grunt, to see if the moose wouldn't move along a bit, just

to

oblige us. But as Billy drew in his breath, one of those tiny fool

flies

that are always blundering around a man's face flew straight down his

throat.

Instead of a call he burst out with a furious, strangling fit of

coughing.

The moose gave a snort, and a wild leap in the water, and galloped away

under

the bank, the way he had come. Mae and I both fired at his vanishing

ears

and horns, but of course – "

"All aboooard!" The conductor's shout rang along

the

platform.

"Line's clear," exclaimed McLeod, rising. "Noo

we'll

be off! Wull ye stay here wi' me, or gang ava' back to yer bed?"

"Here," answered Hemenway, not budging from his

place

on the bench.

The bell clanged, and the powerful machine puffed

out

on its flaring way through the night. Faster and faster came the big

explosive

breaths, until they blended in a long steady roar, and the train was

sweeping

northward at forty miles an hour. The clouds had broken; the night had

grown

colder; the gibbous moon gleamed over the vast and solitary landscape.

It

was a different thing to Hemenway, riding in the cab of the locomotive,

from

an ordinary journey in the passenger-car or an unconscious ride in the

sleeper.

Here he was on the crest of motion, at the fore-front of speed, and the

quivering

engine with the long train behind it seemed like a living creature

leaping

along the track. It responded to the labour of the fireman and the

touch

of the engineer almost as if it could think and feel. Its pace

quickened

without a jar; its great eye pierced the silvery space of moonlight

with

a shaft of blazing yellow; the rails sang before it and trembled behind

it;

it was an obedient and joyful monster, conquering distance and

devouring

darkness.

On the wide level barrens beyond the Tete-a-Gouche

River

the locomotive reached its best speed, purring like a huge cat and

running

smoothly. McLeod leaned back on his bench with a satisfied air.

"She's doin' fine, the nicht," said he. "Ah'm

thinkin',

whiles, o' yer auld Seelverhorrns. Whaur is he noo? Awa' up on Hogan's

Pond,

gallantin' around i' the licht o' the mune wi' a lady moose, an' the

gladness

juist bubblin' in his hairt. Ye're no sorry that he's leeyin' yet, are

ye,

Dud?"

"Well," answered Hemenway slowly, between the

puffs of

his pipe, "I can't say I'm sorry that he's alive and happy, though I'm

not

glad that! lost him. But he did his best, the old rogue; he played a

good

game, and he deserved to win. Where he is now nobody can tell. He was

travelling

like a streak of lightning when I last saw him. By this time he may

be – "

"What's yon?" cried McLeod, springing up. Far

ahead,

in the narrow apex of the converging rails, stood a black form,

motionless,

mysterious. McLeod grasped the whistle-cord. The black form loomed

higher

in the moonlight and was clearly silhouetted against the horizon

– a

big

moose standing across the track. They could sec his grotesque head, his

shadowy

horns, his high, sloping shoulders. The engineer pulled the cord. The

whistle

shrieked loud and long.

The moose turned and faced the sound. The glare of

the

headlight fascinated, challenged, angered him. There he stood defiant,

front

feet planted wide apart, head lowered, gazing steadily at the unknown

enemy

that was rushing toward him. He was the monarch of the wilderness.

There

was nothing in the world that he feared, except those strange-smelling

little

beasts on two legs who crept around through the woods and shot fire out

of

sticks. This was surely not one of those treacherous animals, but some

strange

new creature that dared to shriek at him and try to drive him out of

its

way. He would not move. He would try his strength against this big

yellow-eyed

beast.

There

he stood defiant,

front feet wide apart.

"Losh!" cried McLeod; "he's gaun' to

fecht us!"

and he dropped the cord, grabbed the levers, and threw the steam off

and

the brakes on hard. The heavy train slid groaning and jarring along the

track.

The moose never stirred. The fire smouldered in his small narrow eyes.

His

black crest was bristling. As the engine bore down upon him, not a rod

away,

he reared high in the air, his antlers flashing in the blaze, and

struck

full at the headlight with his immense fore feet. There was a

shattering

of glass, a crash, a heavy shock, and the train slid on through the

darkness,

lit only by the moon.

Thirty or forty yards beyond, the

momentum was

exhausted and the engine came to a stop. Hemenway and McLeod clambered

down

and ran back, with the other trainmen and a few of the passengers. The

moose

was lying in the ditch beside the track, stone dead and frightfully

shattered.

But the great head and the vast, spreading antlers were intact.

"Seelver-horrns, sure eneugh!" said McLeod,

bending over

him. "He was crossin' frae the Nepissiguit to the Jacquet; but he didna

get

across. Weel, Dud, are ye glad? Ye hae killt yer first moose!"

"Yes," said Hemenway, "it's my first moose. But

it's

your first moose, too. And I think it's our last. Ye gods, what a

fighter!"

|