THE MIRACLE OF PURUN BHAGAT

|

The night

we felt the earth would move

We stole and plucked him by

the hand,

Because we loved him with the love

That knows but cannot

understand.

And when

the roaring hillside broke,

And all our world fell down in

rain,

We saved him, we the Little Folk;

But lo! he does not come

again!

Mourn

now, we saved him for the sake

Of such poor love as wild ones

may.

Mourn ye! Our brother will not wake,

And his own kind drive us away!

Dirge of the Langurs.

|

The Miracle of Purun Bhagat

THERE

was once a man in India who was Prime Minister of one of the

semi-independent native States in the northwestern part of the country.

He was a Brahmin, so high-caste that caste ceased to have any

particular meaning for him; and his father had been an important

official in the gay-coloured tag-rag and bobtail of an old-fashioned

Hindu Court. But as Purun Dass grew up he felt that the old order of

things was changing, and that if any one wished to get on in the world

he must stand well with the English, and imitate all that the English

believed to be good. At the same time a native official must keep his

own master’s favour. This was a difficult game, but the quiet,

close-mouthed young Brahmin, helped by a good English education at a

Bombay University, played it coolly, and rose, step by step, to be

Prime Minister of the kingdom. That is to say, he held more real power

than his master, the Maharajah.

When

the old king — who was suspicious of the English, their railways and

telegraphs — died, Purun Dass stood high with his young successor, who

had been tutored by an Englishman; and between them, though he always

took care that his master should have the credit, they established

schools for little girls, made roads, and started State dispensaries

and shows of agricultural implements, and published a yearly blue-book

on the “Moral and Material Progress of the State,” and the Foreign

Office and the Government of India were delighted. Very few native

States take up English progress altogether, for they will not believe,

as Purun Dass showed he did, that what was good for the Englishman must

be twice as good for the Asiatic. The Prime Minister became the

honoured friend of Viceroys, and Governors, and Lieutenant-Governors,

and medical missionaries, and common missionaries, and hard-riding

English officers who came to shoot in the State preserves, as well as

of whole hosts of tourists who travelled up and down India in the cold

weather, showing how things ought to be managed. In his spare time he

would endow scholarships for the study of medicine and manufactures on

strictly English lines, and write letters to the “Pioneer,” the

greatest Indian daily paper, explaining his master’s aims and objects.

At

last he went to England on a visit, and had to pay enormous sums to the

priests when he came back; for even so high-caste a Brahmin as Purun

Dass lost caste by crossing the black sea.

In

London he met and talked with every one worth knowing — men whose names

go all over the world — and saw a great deal more than he said. He was

given honorary degrees by learned universities, and he made speeches

and talked of Hindu social reform to English ladies in evening dress,

till all London cried, “This is the most fascinating man we have ever

met at dinner since cloths were first laid.”

When

he returned to India there was a blaze of glory, for the Viceroy

himself made a special visit to confer upon the Maharajah the Grand

Cross of the Star of India — all diamonds and ribbons and enamel; and

at the same ceremony, while the cannon boomed, Purun Dass was made a

Knight Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire; so that his name

stood Sir Purun Dass, K.C.I.E.

That

evening, at dinner in the big Viceregal tent, he stood up with the

badge and the collar of the Order on his breast, and replying to the

toast of his master’s health, made a speech few Englishmen could have

bettered.

Next

month, when the city had returned to its sunbaked quiet, he did a thing

no Englishman would have dreamed of doing; for, so far as the world’s

affairs went, he died. The jewelled order of his knighthood went back

to the Indian Government, and a new Prime Minister was appointed to the

charge of affairs, and a great game of General Post began in all the

subordinate appointments. The priests knew what had happened, and the

people guessed; but India is the one place in the world where a man can

do as he pleases and nobody asks why; and the fact that Dewan Sir Purun

Dass, K. C. I. E., had resigned position, palace, and power, and taken

up the begging-bowl and ochre-coloured dress of a Sunnyasi, or holy

man, was considered nothing extraordinary. He had been, as the Old Law

recommends, twenty years a youth, twenty years a fighter, — though he

had never carried a weapon in his life, — and twenty years head of a

household. He had used his wealth and his power for what he knew both

to be worth; he had taken honour when it came his way; he had seen men

and cities far and near, and men and cities had stood up and honoured

him. Now he would let these things go, as a man drops the cloak he no

longer needs.

Behind

him, as he walked through the city gates, an antelope skin and

brass-handled crutch under his arm, and a begging-bowl of polished

brown coco-de-mer in his hand, barefoot, alone,

with eyes cast on the ground — behind him they were firing salutes from

the bastions in honour of his happy successor. Purun Dass nodded. All

that life was ended; and he bore it no more ill-will or good-will than

a man bears to a colourless dream of the night. He was a Sunnyasi — a

houseless, wandering mendicant, depending on his neighbours for his

daily bread; and so long as there is a morsel to divide in India,

neither priest nor beggar starves. He had never in his life tasted

meat, and very seldom eaten even fish. A five-pound note would have

covered his personal expenses for food through any one of the many

years in which he had been absolute master of millions of money. Even

when he was being lionized in London he held before him his dream of

peace and quiet — the long, white, dusty Indian road, printed all over

with bare feet, the incessant, slow-moving traffic, and the

sharp-smelling wood smoke curling up under the fig-trees in the

twilight, where the wayfarers sit at their evening meal.

When

the time came to make that dream true the Prime Minister took the

proper steps, and in three days you might more easily have found a

bubble in the trough of the long Atlantic seas than Purun Dass among

the roving, gathering, separating millions of India.

At

night his antelope skin was spread where the darkness overtook him —

sometimes in a Sunnyasi monastery by the roadside; sometimes by a mud

pillar shrine of Kala Pir, where the Jogis, who are another misty

division of holy men, would receive him as they do those who know what

castes and divisions are worth; sometimes on the outskirts of a little

Hindu village, where the children would steal up with the food their

parents had prepared; and sometimes on the pitch of the bare

grazing-grounds, where the flame of his stick fire waked the drowsy

camels. It was all one to Purun Dass — or Purun Bhagat, as he called

himself now. Earth, people, and food were all one. But unconsciously

his feet drew him away northward and eastward; from the south to

Rohtak; from Rohtak to Kurnool; from Kurnool to ruined Samanah, and

then up-stream along the dried bed of the Gugger river that fills only

when the rain falls in the hills, till one day he saw the far line of

the great Himalayas.

Then

Purun Bhagat smiled, for he remembered that his mother was of Rajput

Brahmin birth, from Kulu way — a Hill-woman, always homesick for the

snows — and that the least touch of Hill blood draws a man at the end

back to where he belongs.

“Yonder,”

said Purun Bhagat, breasting the lower slopes of the Sewaliks, where

the cacti stand up like seven-branched candlesticks — “yonder I shall

sit down and get knowledge”; and the cool wind of the Himalayas

whistled about his ears as he trod the road that led to Simla.

The

last time he had come that way it had been in state, with a clattering

cavalry escort, to visit the gentlest and most affable of Viceroys; and

the two had talked for an hour together about mutual friends in London,

and what the Indian common folk really thought of things. This time

Purun Bhagat paid no calls, but leaned on the rail of the Mall,

watching that glorious view of the Plains spread out forty miles below,

till a native Mohammedan policeman told him he was obstructing traffic;

and Purun Bhagat salaamed reverently to the Law, because he knew the

value of it, and was seeking for a Law of his own. Then he moved on,

and slept that night in an empty hut at Chota Simla, which looks like

the very last end of the earth, but it was only the beginning of his

journey.

He

followed the Himalaya-Thibet road, the little ten-foot track that is

blasted out of solid rock, or strutted out on timbers over gulfs a

thousand feet deep; that dips into warm, wet, shut-in valleys, and

climbs out across bare, grassy hill-shoulders where the sun strikes

like a burning-glass; or turns through dripping, dark forests where the

tree-ferns dress the trunks from head to heel, and the pheasant calls

to his mate. And he met Thibetan herdsmen with their dogs and flocks of

sheep, each sheep with a little bag of borax on his back, and wandering

wood-cutters, and cloaked and blanketed Lamas from Thibet, coming into

India on pilgrimage, and envoys of little solitary

Hill-states, posting furiously on ring-streaked and piebald ponies, or

the cavalcade of a Rajah paying a visit; or else for a long, clear day

he would see nothing more than a black bear grunting and rooting below

in the valley. When he first started, the roar of the world he had left

still rang in his ears, as the roar of a tunnel rings long after the

train has passed through; but when he had put the Mutteeanee Pass

behind him that was all done, and Purun Bhagat was alone with himself,

walking, wondering, and thinking, his eyes on the ground, and his

thoughts with the clouds.

One

evening he crossed the highest pass he had met till then — it had been

a two days’ climb — and came out on a line of snow-peaks that banded

all the horizon — mountains from fifteen to twenty thousand feet high,

looking almost near enough to hit with a stone, though they were fifty

or sixty miles away. The pass was crowned with dense, dark forest —

deodar, walnut, wild cherry, wild olive, and wild pear, but mostly

deodar, which is the Himalayan cedar; and under the shadow of the

deodars stood a deserted shrine to Kali — who is Durga, who is Sitala,

who is sometimes worshipped against the smallpox.

Purun

Dass swept the stone floor clean, smiled at the grinning statue, made

himself a little mud fireplace at the back of the shrine, spread his

antelope skin on a bed of fresh pine-needles, tucked his bairagi

— his brass-handled crutch — under his armpit, and sat

down to rest.

Immediately

below him the hillside fell away, clean and cleared for fifteen hundred

feet, where a little village of stone-walled houses, with roofs of

beaten earth, clung to the steep tilt. All round it the tiny terraced

fields lay out like aprons of patchwork on the knees of the mountain,

and cows no bigger than beetles grazed between the smooth stone circles

of the threshing-floors. Looking across the valley, the eye was

deceived by the size of things, and could not at first realize that

what seemed to be low scrub, on the opposite mountain-flank, was in

truth a forest of hundred-foot pines. Purun Bhagat saw an eagle swoop

across the gigantic hollow, but the great bird dwindled to a dot ere it

was half-way over. A few bands of scattered clouds strung up and down

the valley, catching on a shoulder of the hills, or rising up and dying

out when they were level with the head of the pass. And “Here shall I

find peace,” said Purun Bhagat.

Now,

a Hill-man makes nothing of a few hundred feet up or down, and as soon

as the villagers saw the smoke in the deserted shrine, the village

priest climbed up the terraced hillside to welcome the stranger.

When

he met Purun Bhagat’s eyes — the eyes of a man used to control

thousands — he bowed to the earth, took the begging-bowl without a

word, and returned to the village, saying, “We have at last a holy man.

Never have I seen such a man. He is of the Plains — but pale-coloured —

a Brahmin of the Brahinins.” Then all the housewives of the village

said, “Think you he will stay with us?” and each did her best to cook

the most savory meal for the Bhagat. Hill-food is very simple, but with

buckwheat and Indian corn, and rice and red pepper, and little fish out

of the stream in the valley, and honey from the flue-like hives built

in the stone walls, and dried apricots, and turmeric, and wild ginger,

and bannocks of flour, a devout woman can make good things, and it was

a full bowl that the priest carried to the Bhagat. Was he going to

stay? asked the priest. Would he need a chela — a

disciple — to beg for him? Had he a blanket against the cold weather?

Was the food good?

Purun

Bhagat ate, and thanked the giver. It was in his mind to stay. That was

sufficient, said the priest. Let the begging-bowl be placed outside the

shrine, in the hollow made by those two twisted roots, and daily should

the Bhagat be fed; for the village felt honoured that such a man — he

looked timidly into the Bhagat’s face — should tarry among them.

That

day saw the end of Purun Bhagat’s wanderings. He had come to the place

appointed for him — the silence and the space. After this, time

stopped, and he, sitting at the mouth of the shrine, could not tell

whether he were alive or dead; a man with control of his limbs, or a

part the hills, and the clouds, and the shifting rain sunlight. He

would repeat a Name softly to himself a hundred hundred times, till, at

each repetition, he seemed to move more and more out of his body,

sweeping up to the doors of some tremendous discovery; but, just as the

door was opening, his body would drag him tack, and, with grief, he

felt he was locked up again in the flesh and bones of Purun Bhagat.

Every

morning the filled begging-bowl was laid silently in the crutch of the

roots outside the shrine. Sometimes the priest brought it; sometimes a

Ladakhi trader, lodging in the village, and anxious to get merit,

trudged up the path; but, more often, it was the woman who had cooked

the meal overnight; and she would murmur hardly above her breath:

“Speak for me before the gods, Bhagat. Speak for such a one, the wife

of so-and-so!” Now and then some bold child would be allowed the

honour, and Purun Bhagat would hear him drop the bowl and run as fast

as his little legs could carry him, but the Bhagat never came down to

the village. It was laid out like a map at his feet. He could see the

evening gatherings, held on the circle of the threshing-floors because

that was the only level ground; could see the wonderful unnamed green

of the young rice, the indigo blues of the Indian corn, the dock-like

patches of buckwheat, and, in its season, the red bloom of the

amaranth, whose tiny seeds, being neither grain nor pulse, make a food

that can be lawfully eaten by Hindus in time of fasts.

When

the year turned, the roofs of the huts were all little squares of

purest gold, for it was on the roofs that they laid out their cobs of

the corn to dry. Hiving and harvest, rice-sowing and husking, passed

before his eyes, all embroidered down there on the many-sided plots of

fields, and he thought of them all, and wondered what they all led to

at the long last.

Even

in populated India a man cannot a day sit still before the wild things

run over him as though he were a rock; and in that wilderness very soon

the wild things, who knew Kali’s Shrine well, came back to look at the

intruder. The langurs,

the big gray-whiskered monkeys of the Himalayas, were, naturally, the

first, for they are alive with curiosity; and when they had upset the

begging-bowl, and rolled it round the floor, and tried their teeth on

the brass-handled crutch, and made faces at the antelope skin, they

decided that the human being who sat so still was harmless. At evening,

they would leap down from the pines, and beg with their hands for

things to eat, and then swing off in graceful curves. They liked the

warmth of the fire, too, and huddled round it till Purun Bhagat had to

push them aside to throw on more fuel; and in the morning, as often as

not, he would find a furry ape sharing his blanket. All day long, one

or other of the tribe would sit by his side, staring out at the snows,

crooning and looking unspeakably wise and sorrowful.

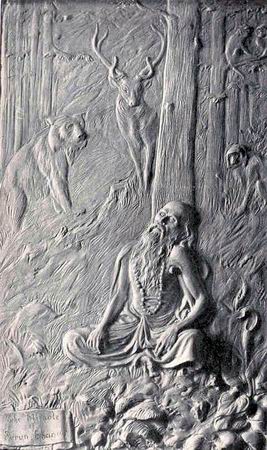

After

the monkeys came the barasingh, that big deer

which is like our red deer, but stronger. He wished to rub off the

velvet of his horns against the cold stones of Kali’s statue, and

stamped his feet when he saw the man at the shrine. But Purun Bhagat

never moved, and, little by little, the royal stag edged up and nuzzled

his shoulder. Purun Bhagat slid one cool hand along the hot antlers,

and the touch soothed the fretted beast, who bowed his head, and Purun

Bhagat very softly rubbed and raveled off the velvet. Afterward, the barasingh

brought his doe and fawn — gentle things that mumbled

on the holy man’s blanket — or would come alone at night, his eyes

green in the fire-flicker, to take his share of fresh walnuts. At last,

the muskdeer, the shyest and almost the smallest of the deerlets, came,

too, her big rabbity ears erect; even brindled, silent mushick-nabha

must needs find out what the light in the shrine meant,

and drop out her moose-like nose into Purun Bhagat’s lap, coming and

going with the shadows of the fire. Purun Bhagat called them all “my

brothers,” and his low call of “Bhai! Bhai!” would

draw them from the forest at noon if they were within earshot. The

Himalayan black bear, moody and suspicious — Sona, who has the V-shaped

white mark under his chin—passed that way more than once; and since the

Bhagat showed no fear, Sona showed no anger, but watched him, and came

closer, and begged a share of the caresses, and a dole of bread or wild

berries. Often, in the still dawns, when the Bhagat would climb to the

very crest of the pass to watch the red day walking along the peaks of

the snows, he would find Sona shuffling and grunting at his heels,

thrusting a curious fore-paw under fallen trunks, and bringing it away

with a whoof of impatience; or his early steps

would wake Sona where he lay curled up, and the great brute, rising

erect, would think to fight, till he heard the Bhagat’s voice and knew

his best friend.

Nearly

all hermits and holy men who live apart from the big cities have the

reputation of being able to work miracles with the wild things, but all

the miracle lies in keeping still, in never making a hasty movement,

and, for a long time, at least, in never looking directly at a visitor.

The villagers saw the outline of the

barasingh stalking like a shadow through the dark forest

behind the shrine; saw the minaul, the Himalayan

pheasant, blazing in her best colours before Kali’s statue; and the langurs

on their haunches, inside, playing with the walnut

shells. Some of the children, too, had heard Sona singing to himself,

bear-fashion, behind the fallen rocks, and the Bhagat’s reputation as

miracle-worker stood firm.

Yet

nothing was further from his mind than miracles. He believed that all

things were one big Miracle, and when a man knows that much he knows

something to go upon. He knew for a certainty that there was nothing

great and nothing little in this world: and day and night he strove to

think out his way into the heart of things, back to the place whence

his soul had come.

So

thinking, his untrimmed hair fell down about his shoulders, the stone

slab at the side of the antelope skin was dented into a little hole by

the foot of his brass-handled crutch, and the place between the

tree-trunks, where the begging-bowl rested day after day, sunk and wore

into a hollow almost as smooth as the brown shell itself; and each

beast knew his exact place at the fire. The fields changed their

colours with the seasons; the threshing-floors filled and emptied, and

filled again and again; and again and again, when winter came, the

langurs frisked among the branches feathered

with light snow, till the mother-monkeys brought their sad-eyed little

babies up from the warmer valleys with the spring. There were few

changes in the village. The priest was older, and many of the little

children who used to come with the begging-dish sent their own children

now; and when you asked of the villagers how long their holy man had

lived in Kali’s Shrine at the head of the pass, they answered, “Always.”

Then

came such summer rains as had not been known in the Hills for many

seasons. Through three good months the valley was wrapped in cloud and

soaking mist — steady, unrelenting downfall, breaking off into

thunder-shower after thunder-shower. Kali’s Shrine stood above the

clouds, for the most part, and there was a whole month in which the

Bhagat never saw his village. It was packed away under a white floor of

cloud that swayed and shifted and rolled on itself and bulged upward,

but never broke from its piers — the streaming flanks of the valley.

All

that time he heard nothing but the sound of a million little waters,

overhead from the trees, and underfoot along the ground, soaking

through the pine-needles, dripping from the tongues of draggled fern,

and spouting in newly torn muddy channels down the slopes. Then the sun

came out, and drew forth the good incense of the deodars and the

rhododendrons, and that far-off, clean smell which the Hill people call

“the smell of the snows.” The hot sunshine lasted for a week, and then

the rains gathered together for their last downpour, and the water fell

in sheets that flayed off the skin of the ground and leaped back in

mud. Purun Bhagat heaped his fire high that night, for he was sure his

brothers would need warmth; but never a beast came to the shrine,

though he called and called till he dropped asleep, wondering what had

happened in the woods.

It

was in the black heart of the night, the rain drumming like a thousand

drums, that he was roused by a plucking at his blanket, and stretching

out, felt the little hand of a langur. “It is

better here than in the trees,” he said sleepily, loosening a fold of

blanket; “take it and be warm.” The monkey caught his hand and pulled

hard. “Is it food, then?” said Purun Bhagat. “Wait awhile, and I will

prepare some.” As he kneeled to throw fuel on the fire the langur

ran to the door of the shrine, crooned, and ran back

again, plucking at the man’s knee.

“What

is it? What is thy trouble, Brother?” said Purun Bhagat, for the langur’s

eyes were full of things that he could not tell.

“Unless one of thy caste be in a trap — and none set traps here — I

will not go into that weather. Look, Brother, even the barasingh

comes for shelter!”

The

deer’s antlers clashed as he strode into the shrine, clashed against

the grinning statue of Kali. He lowered them in Purun Bhagat’s

direction and stamped uneasily, hissing through his half-shut nostrils.

“Hai!

Hai! Hai!” said the Bhagat, snapping his fingers. “Is this payment

for a night’s lodging?” But the deer pushed him toward the door, and as

he did so Purun Bhagat heard the sound of something opening with a

sigh, and saw two slabs of the floor draw away from each other, while

the sticky earth below smacked its lips.

“Now

I see,” said Purun Bhagat. “No blame to my brothers that they did not

sit by the fire to-night. The mountain is falling. And yet — why should

I go?” His eye fell on the empty begging-bowl, and his face changed.

“They have given me good food daily since — since I came, and, if I am

not swift, to-morrow there will not be one mouth in the valley. Indeed,

I must go and warn them below. Back there, Brother! Let me get to the

fire.”

The

barasingh backed unwillingly as Purun Bhagat

drove a pine torch deep into the flame, twirling it till it was well

lit. “Ah! ye came to warn me,” he said, rising. “Better than that we

shall do; better than that. Out, now, and lend me thy neck, Brother,

for I have but two feet.”

He

clutched the bristling withers of the barasingh with

his right hand, held the torch away with his left, and stepped out of

the shrine into the desperate night. There was no breath of wind, but

the rain nearly drowned the flare as the great deer hurried down the

slope, sliding on his haunches. As soon as they were clear of the

forest more of the Bhagat’s brothers joined them. He heard, though he

could not see, the langurs pressing about him, and

behind them the

uhh! uhh! of Sona. The rain matted his long white hair into

ropes; the water splashed beneath his bare feet, and his yellow robe

clung to his frail old body, but he stepped down steadily, leaning

against the barasingh. He was no longer a holy

man, but Sir Purun Dass, K. C. I. E., Prime Minister of no small State,

a man accustomed to command, going out to save life. Down the steep,

plashy path they poured all together, the Bhagat and his brothers, down

and down till the deer’s feet clicked and stumbled on the wall of a

threshing-floor, and he snorted because he smelt Man. Now they were at

the head of the one crooked village Street, and the Bhagat beat with

his crutch on the barred windows of the blacksmith’s house as his torch

blazed up in the shelter of the eaves. “Up and out!” cried Purun

Bhagat; and he did not know his own voice, for it was years since he

had spoken aloud to a man. “The hill falls! The hill is falling! Up and

out, oh, you within!”

“It

is our Bhagat,” said the blacksmith’s wife. “He stands among his

beasts. Gather the little ones and give the call.”

It

ran from house to house, while the beasts, cramped in the narrow way,

surged and huddled round the Bhagat, and Sona puffed impatiently.

The

people hurried into the street — they were no more than seventy souls

all told — and in the glare of the torches they saw their Bhagat

holding back the terrified

barasingh, while the monkeys plucked piteously at his

skirts, and Sona sat on his haunches and roared.

“Across

the valley and up the next hill!” shouted Purun Bhagat. “Leave none

behind! We follow!”

Then

the people ran as only Hill folk can run, for they knew that in a

landslip you must climb for the highest ground across the valley. They

fled, splashing through the little river at the bottom, and panted up

the terraced fields on the far side, while the Bhagat and his brethren

followed. Up and up the opposite mountain they climbed, calling to each

other by name — the roll-call of the village — and at their heels

toiled the big barasingh, weighted by the failing

strength of Purun Bhagat. At last the deer stopped in the shadow of a

deep pine-wood, five hundred feet up the hillside. His instinct, that

had warned him of the coming slide, told him he would be safe here.

Purun

Bhagat dropped fainting by his side, for the chill of the rain and that

fierce climb were killing him; but first he called to the scattered

torches ahead, “Stay and count your numbers ”; then, whispering to the

deer as he saw the lights gather in a cluster: “Stay with me, Brother.

Stay — till — I — go!”

There

was a sigh in the air that grew to a mutter, and a mutter that grew to

a roar, and a roar that passed all sense of hearing, and the hillside

on which the villagers stood was hit in the darkness, and rocked to the

blow. Then a note as steady, deep, and true as the deep C of the organ

drowned everything for perhaps five minutes, while the very roots of

the pines quivered to it. It died away, and the sound of the rain

falling on miles of hard ground and grass changed to the muffled drum

of water on soft earth. That told its own tale.

Never

a villager — not even the priest — was bold enough to speak to the

Bhagat who had saved their lives. They crouched under the pines and

waited till the day. When it came they looked across the valley and saw

that what had been forest, and terraced field, and track-threaded

grazing-ground was one raw, red, fan-shaped smear, with a few trees

flung head-down on the scarp. That red ran high up the hill of their

refuge, damming back the little river, which had begun to spread into a

brick-coloured lake. Of the village, of the road to the shrine, of the

shrine itself, and the forest behind, there was not trace. For one mile

in width and two thousand feet in sheer depth the mountain-side had

come away bodily, planed clean from head to heel.

And

the villagers, one by one, crept through the wood to pray before their

Bhagat. They saw the barasingh standing over him,

who fled when they came near, and they heard the langurs wailing

in the branches, and Sona moaning up the hill; but their Bhagat was

dead, sitting cross-legged, his back against a tree, his crutch under

his armpit, and his face turned to the northeast.

The

priest said: “Behold a miracle after a miracle, for in this very

attitude must all Sunnyasis be buried! Therefore where he now is we

will build the temple to our holy man.”

They

built the temple before a year was ended — a little stone-and-earth

shrine — and they called the hill the Bhagat’s Hill, and they worship

there with lights and flowers and offerings to this day. But they do

not know that the saint of their worship is the late Sir Purun Dass, K.

C. I. E., D. C. L., Ph. D., etc., once Prime Minister of the

progressive and enlightened State of Mohiniwala, and honorary or

corresponding member of more learned and scientific societies than will

ever do any good in this world or the next.

|

Oh,

light was the world that he weighed in his hands

Oh, heavy the tale of his fiefs and his lands!

He has gone from the guddee and put on the shroud,

And departed in guise of bairagi avowed!

Now

the white road to Delhi is mat for his feet,

The sal and the kikar must

guard him from heat;

His home is the camp, and the waste, and the crowd —

He is seeking the Way as bairagi avowed!

He

has looked upon Man, and his eyeballs are clear

(There was One; there is One, and but One, saith Kabir)

The Red Mist of Doing has thinned to a cloud —

He has taken the Path for bairagi avowed!

To

learn and discern of his brother the clod,

Of his brother the brute, and his brother the God.

He has gone from the council and put on the shroud

(“Can ye hear?” saith Kabir), a bairagi avowed!

|

Click  here to continue to the next chapter of

The Second Jungle Book.

here to continue to the next chapter of

The Second Jungle Book.

|