X

DECORATIVE MATERIAL

THE

decorative material available for a yard is not large.

At least, it should not be large in bulk, and it is not in variety.

Passing

a shop in the metropolis, the other day, I found along the walk before

it

huge capitals of columns, well-curbs from Italy, stone benches, marble

lions

and heraldic monsters, and observed that they were offered for sale as

fitments

for gardens. They will go to New Jersey and will help some rich man to

pretend

that a fine crop of Roman temples and Renaissance palaces has just gone

to

seed on his premises. We may advocate formality with a grace, for it is

only

humanness; but there are situations in which it is bombast, or

hypocrisy,

to strew our ground with what obviously belongs out of it. If we will

have

them in small spaces, then fonts, benches, termini, capitals,

well-curbs,

short columns, bases and their like are better than large figures,

in-as-much

as they dominate the ground less arrogantly, and the ground shows for

itself.

I

suppose there is no law against the use of Italian

wells in American parks, any more than I suppose there is a lack of

Americans

who can design American wells for Italian parks, but these objects,

weighing

a ton or two--I am not speaking of the designers now, but of their

well-curbs--require large surroundings and backgrounds, not of

shrubbery

alone, but of stately trees; in short, the setting of a large

landscape.

If we have an important tree in the city yard we shall always live in

the

shadow, for there will be no room for anything else. Yet a large oak,

or

even a maple, would be no more out of place on the spot where we are

supposed

to dry the clothes than a big piece of sculpture would be. A statue,

unless

it is small and simply pedestaled, demands room. It subordinates to

itself

a space of three times its greatest dimension. It can be exhibited in

city

squares and parked spaces with surroundings of flowers and ornate

leafage;

indeed, it should have this footing in the natural-beautiful, so long

as

it is out of doors. In a small garden we can not dignify a work of art

by

floriculture to the degree it may deserve, for it must serve as a part

in

a decorative scheme; otherwise the surroundings will be such as to

create

a ridiculous contrast between the statue and the setting. Imagine, if

you

please, a marble Apollo or a bronze Mercury with a whitewashed fence

behind,

and the clothes hung to dry before it. Yet, if we removed the clothes

and

substituted a wall, which comported in solidity with the material of

the

statue, the effect would be beautiful, provided, to be sure, that in

our

composition we had subdued all to that statue: given an important

position

to it at the back or corner, massed flowers about it, arched it with

vines,

made reflections of it in a fountain-basin, maybe, led toward it with

walks

and repeated its upright attitude in vines and potted trees, so that it

would

not stand stark and unsupported. Here is a scheme wherein the garden is

so

subordinated, yet as there are four points, either of which could be

made

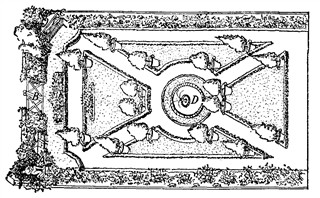

focal, the figure might with equal fitness be placed at A, or B, or C,

or

D. If placed either at A or C, something might be added, for balance'

sake,

since the plan is formal, at the opposite side--a bench, a font, a small rockery: nothing

of exactly equal size, not anything

in kind, because two pieces of sculpture would be too many for a single

yard,

and it would be carrying formalism to monotony to repeat one corner in

its

opposite.

Fig. 28.

In this

device are two vistas, and we require something

at the end of each. If the statue be placed at B, then the semilunes

that

flank it, and that end the paths, can be filled with flowering shrubs

of

some size and showiness, not forgetting that the statue itself will

require

greenery, for white and green make the one brisk contrast that is

esthetic.

Its pedestal will be high enough merely to lift it into view, a couple

of

feet sufficing for a life-size figure. Statuary is raised on lofty

bases

only when it is desired to make it "tell" at a distance. It would be

the

twelve-foot height of absurdity to put a twelve-foot pedestal under any

figure

with which we sought to ornament our yard. Mounted in that fashion its

place

would be the front of a capitol or city hall. And mind, I am rather

insisting

that while there may be a statuette there shall be no statue, unless

there

is a wall for a background, and we do not build many walls in this

country.

I can remember hardly a dozen on the island of Manhattan, that surround

estates

of consequence, though I do recall some ancient defenses of the sort in

its

upper districts, now gone to rack and ruin, through the cutting of new

streets

and subways, the building of elevated roads and viaducts, the

appropriation

of adjacent fields for tenements, and the incoming of that disturbing

horde

which defies the blandishments of soap. With such a canvas as any one

of

these estates offered in its best day, what pictures might not one

create

upon it! May I draw one here, of what I would have in this garden of my

fancy?

It is but rudely indicated in these lines, of course, but they will

help

to explain my meaning:

I will

suppose the space, then, to be forty by a hundred

feet. It shall be commanded by a house in which the architectural lines

will

not be extinguished by a mask of brick, but will show timber beams and

braces,

latticed windows and vines reaching above its first story. The wide,

low

windows giving on the yard shall often be left open, for the view, the

perfume

and the coolness. The ground shall be quite surrounded by a brick wall

eight

feet high, for this is my cloister of evening meditation. There is

plenty

of world outside, and I shall see it often, but here I withdraw from

it.

A brick wall is cold and trite? So it would be if we left it at that,

merely;

but there are to be a stone coping and borders of half bricks affording

a

strong and gritty edge to the construction; there is to be a paneled

base;

there are to be a dozen terra-cotta insets with conventional ornament,

like

an acanthus, leaf, or any such, while at C there is to be an alcove a

foot

or more deep and three feet high, to contain some rare exotic, or

perhaps

no more than an urn of stone. Should I have more land, the wall will be

pierced

at B by a gate leading, I hope, to fair acres and pleasing rambles;

possibly

to some quiet stream or wood of mystery. This gate should be of heavy

wood,

and either stained green, with hand-wrought iron hinges, or, if the

wood

were old enough to have taken on a ripe and quiet tone, it would be

left

of its natural color. The wall should be almost hidden by vines: sweet

pea

and morning-glory, where the sun shone, honeysuckle, clematis,

woodbine,

and at the back two or three trees should throw an afternoon shade over

the

ground. On top of the wall at a farther corner, or, better, built into

the

masonry, would be a bird-house where, if possible, some starlings

should

be domesticated and protected. I don't know whether these soft-voiced

musicians

eat bees or not, but if bees disagree with them there should be a hive

somewhere

among the shrubbery, near the back, that their tuneful hum might be

added

to the restful whispering of the leafage and the tinkle of water, which

would

spray from a little fountain in the pool at the center of the yard. The

long

beds on either side of the walk should be filled with flowers,

perennials

like roses and lilies, beside zinnias, marigolds, nasturtiums,

Canterbury

bells, foxgloves, pansies, dahlias, asters and chrysanthemums; and

where

the flowers assembled thickest, in the farther left corner, I would

place

my statue--an ancient bronze with a fine patina, in which the hue

soberly

yet richly varied through yellow green to purplish olive, but if I

could

not have my bronze, then a figure in marble, solid and restful in

attitude,

a pagan goddess or a Christian saint: no hurlers of spears, or

wrestlers,

or boxers, or martyrs, or dying soldiers, but a figure that stood its

ground

with the firmness of a caryatid. And it should not be the prettiness of

yesterday, freshly polished in an Italian studio-shop, but an old piece

from

Pentelicus, its snow softened to cream, its hard shininess gone, its

neat

chiseling of draperies blunted by contact with a sometime admiring,

sometime

forgetful world. At the opposite end of the cross-walk would be an easy

bench,

not an affair of roots glued over a framework of carpentry, the product

of

a town factory, but an honestly fashioned seat of hewn timber, circling

or

half circling the tree trunk, if the tree were big enough to justify

and

support it. One thing this bench would not be, and that is, a cast-iron

copy

of a so-called rustic seat. A chair or bench might be made of iron, yet

be

artistic, therefore, honest, and it might fit into a garden scheme.

Maybe

if this were suggested to a Japanese designer he could produce one. But

why

should the iron pretend to be wood, any more than wood masquerade as

iron

? Let us have homely frankness about us, rather than supposedly ornate

sham--for,

as a matter of fact, sham is seldom ornate. I do not admire those beds,

designed

for New York flats, that are folded up by day, when they pretend to be

innocent

ice-chests, pianos and sideboards. Every observer knows them for

designing

and insomnious frauds. I do not admire chromos that affect to be real

oil-paintings, done by hand, nor Philadelphia rugs that make believe to

have

been woven in Shiraz, nor coffee that grew on chicory, nor wine

composed

of dye and vinegar, nor milk compounded of chalk and water, nor any

other

thing that goes through the form of being better than it is. Sand in

its

place is useful, even beautiful, but its place is not inside of the

sugar-bowl.

And so I would avoid in and about the garden all those pretenses in

which

we observe a gross and ridiculous disparity of material and appearance,

or

of function and effect. I would not, for example, suspend a gypsy

kettle

from three sticks and plant heliotrope therein, making believe to boil

this

herb over a slow fire which causes the blossoms to emerge, in place of

smoke.

It is quite permissible to string a hammock in the angle of the wall.

Your

naps and contortions will not be exhibited to the neighbors.

The

arms of the Maltese cross, to which you will trace

some likeness in the plan, are lawns, and these should be leveled by

persistent

rolling and kept as green, fresh and unmixed with anything other than

grass

and clover as sound seed, fresh water and a diligent war on weeds can

make

them. Every weed removed gives so much the more space for grass, and in

time

a carpet is formed into which interloping thistles, dandelions and

ragweed

find it increasingly hard to penetrate. For association's sake I would

edge

the gravel walks that intersect the ground with box, and keep it in

borders

not over twenty inches high, always neatly trimmed, and green all

through

the year. At the points of the lawns should be placed tubs of oak with

iron

handles,. for here is legitimate use of metal, and those vessels should

contain

thick-growing little trees or solid-looking bushes. If all the trees

were

hemlocks, yews and spruces, so much the better, as they repeat and

intensify,

yet harmonize, the upright lines of the statue and the house sides, and

increase

their altitude, if there are not too many of them; for an upright by

itself

is taller than in company, just as Niagara, because of its breadth,

loses

the height which would be readily apparent if we took any ten-foot span

of

the cataract, and closed it in with rock. And these tubbed trees should

be

darkly, serenely green, standing with an air of some fixity, like the

statue

and other fitments, and contrasting pleasantly with the large and

fluent

forms of the maples, magnolias, elms, lindens or gingkos that overhung

the

wall at the back. If these taller, rounder trees grew really outside of

the

Walls, it would be pleasanter than if they grew within, for the space

is

so small that it would be a hardship to sacrifice it, even for a tree,

especially

when all the picturesqueness of the latter could be effected without

putting

the stem on the hither side of our boundaries. The space indicated for

trees

in the plan could be filled by such bushes as the syringa, lilac,

laurel,

weigelia and the larger or taller growing roses. The pool should be of

clearest

water, led from a mountain spring, and containing a few lilies--only a

few,

because one would wish to look at the fish swimming beneath the pads,

for

if there were no fish there would be mosquitoes, unless there were a

current

so strong that those pests desisted from laying their eggs on the

surface,

in which case it would be too agitated for the successful raising of

lilies,

and the fish might grow discontented, also.

If

there were no pool and no statue, a clump of tall,

feathery grass, such as we have brought from the South American pampas,

or

an urn filled with the Kenilworth ivy, a fast and easy grower, would

serve

as decorative points--hubs for the radii of our composition. Or, at B

we

could train an arch of roses or other vines, preferably an arch of wood

or

bamboo, yet permissibly of wire net, for this wire tells what it is

made

of, and does not pretend to be porcelain, sandalwood or mahogany. And

if

there is a vase, let it be of stone or pottery, not of cement; this not

alone

for appearance' but for endurance' sake. Cement has its uses, as in the

casing

of the pool, but the making of gravestones, urns and statuary from this

material

is forbidden by the law of esthetics. Have you ever looked upon a

statue

of cement? If so, it is too solemn a spectacle to forget. Don't have

anything

in the garden that is molded by machinery, unless it may be

drain-pipes.

Let the work show the touch of the human hand, and let it be a

duplicate

of nothing that exists elsewhere. Yet, if there were a city ordinance

that

compelled me to have a statue in the yard, and I found after a search

through

my garments that I had not the price of a Venus of Milo in marble--a

discovery

sure to fill me with astonishment--I would doubtless buy a figure of

plaster;

for the Italians make faithful and artistic copies in this cheap

medium.

They are good enough for our museums and art schools, and ought, by

that

token, to be good enough for gardens. Hm! They are not rained on, in

the

art schools. But if you do set up a plaster image, paint it first, just

to

take off its raw whiteness. Use a cream-colored or yellow-brown

pigment,

or even a pale green, and if the figure is chipped, cover the chipped

place

with another touch of the color.

I think

I have not mentioned Japanese lanterns as garden

possibilities. They are alien enough, to be sure, yet they are quaint

and

decorative, and more modest than the importations from Italian palaces

and

convents with which so many owners of palaces try to foreignize the

landscape

of New York and Massachusetts. I am not speaking of those paper

lanterns,

gay and pretty ornaments, familiar to lawn-parties-luminous flowers of

the

night--but of the stone and metal inventions that are used in and about

the

temples of Japan. They stand on pedestals, somewhat like binnacles on

shipboard,

they have overhanging roofs like pagodas, and they may contain lamps or

candles.

Their little windows, softly shining through leaves, suggest the

comforting

lights of home. These devisements are works of art, and while there is

a

similarity in their construction, each is an individual conceit; that

it

is which makes them art. Much gilded, trifling, insincere ornament is

made

for garden use, but it behooves us to be content with simple things and

let

our walks through little kingdoms teach constancy and simplicity. My

garden

should have those things that are sweetly familiar, unexcitant, of

conceded

loveliness.

The

best of the garden, however, is what you put into

it, rather than what comes out of it. It is the satisfaction of your

tastes,

and the bettering of them, the thought and sentiment you express in

planting

and gathering, the innocence and quiet of mind that you take to the

seeding,

trimming and watering, that are the real rewards. In time the garden

comes

to mean a part of yourself, just as your pictures and your library are

a

part, and it will be modest or bombastic, delicate or vulgar, trivial

or

sincere, ingenuous or artificial, according as you possess those

qualities.

As it flourishes it may disclose a broad mind and generous nature, or

it

may prove in its dryness and ill feeding, a habit of pelf and a

grudging

of care. If it is worth while to have a garden at all, it is probably

worth

while to have one that will humble the neighbors; but this does not

imply

mere show: it implies content with your work and enjoyment of what you

have.

I often wonder if content is not one of the lost arts, at least, among

the

residents of towns. I believe it has a close relation to the art of

gardening.

I ought to have said, the craft of gardening, for if we look on this

employment

as an art, our pleasure in it may be the higher, yet I. fear it will be

the

narrower. We can treat the flower-bed as we would paint a picture or

shape

a statue; we can make it poetic and endow it with fine and sensitive

qualities,

and we should do so; but it is best as a broad and intimate human

expression.

We may not approve a garden, but if the motive in creating it has been

sincere,

if it indicates a love of the beautiful and a reverence for life, we

must

respect it, for in doing so we respect its maker.

THE END

Click the Web-Textures icon to return to

the On-Line Books Content Page:

|