|

1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

|

1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

XX

OBSERVATIONS ON A SALMON RIVER

ANGLING

THE charms of angling are anticipation and solitude. It takes much time and practice to become proficient, and you must be keen and quick and have great delicacy of touch to become a good angler. It cultivates quickness, self-control, and above all things, patience.

Angling is a sporting fight between you and the fish and, as no two families of fishes fight alike, you are matching your brains and cleverness against the ingenuity of the fish.

It also cultivates a habit of observation which is so necessary if one would enjoy life and nature, and it takes one to beautiful rivers at nature’s most attractive season when there is so much that is interesting to observe both in bird and in plant life.

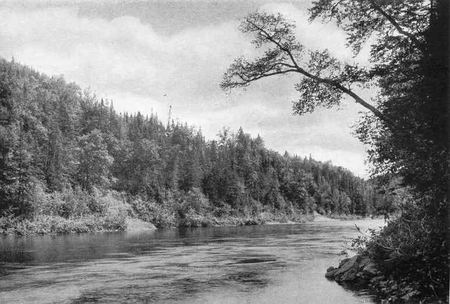

The solitude on the Canadian rivers is broken by the pleasant sound of running waters, the note of a king-fisher or the drumming of a partridge, and the typical clinking sound of iron-shod canoe poles as a canoe is driven up stream.

GAME FISH

From the standpoint of a fisherman I divide game fish into two classes namely, the forked-tailed and the square-tailed fishes.

The former travel great distances, swim rapidly, and are nearly all surface feeders and strong surface fighters.

The latter dwell on the bottom, are bottom feeders, and generally have a local habitat.

The forked tail has been given to the swordfish, tarpon, bonefish, bluefish, spearfish, dolphin, and all the pampano, herring, and mackerel tribes.

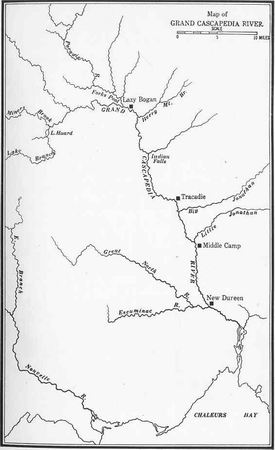

Map of Grand Cascapedia River

The tail is forked for the purpose of leaving a free space directly behind the axis of the body where the stream-lines following the sides of the moving fish converge. This means ease and speed in swimming. A round or square tail is a drag for it fills this space.

The whales and porpoises have horizontal forked tails which they move up and down, for they rise to the surface when swimming.

Among the square-tailed fish I classify the bass family, the snappers and groupers, and the salmon family.

The square-tailed fish are slow swimmers and seldom travel far. Those that do, such as the drumfish and the striped bass, proceed at a leisurely pace. The latter during their yearly pilgrimages travel and feed so close inshore that it has been possible by netting to almost destroy what was at one time one of the most numerous of our game fishes.

The forked-tail fish journey great distances and often at a high rate of speed, seeking food or a change of water temperature, and do not hibernate as do some of the square-tailed fish.

The square tail of the salmon is one proof, to my mind, that when they leave a river they do not journey far but dwell in the deep sea near the mouth of their summer home.

Although the seafood of the salmon when off the mouth of a river is known to be herring and the like, their square tails would lead one to believe that they are bottom feeders and that they feed leisurely and well, which would account for the fresh-run fish’s superabundance of fat.

According to Alexander Agassiz the pelagic animals are very short-lived but they reproduce marvelously. Some of the Copepods, which are minute crustaceans, have no less than thirty generations in three weeks.

As they are constantly dying there is a shower of food falling over the ocean floor which joins the food that comes from the littoral regions. It is stated that there is a thick broth of food over wide areas of sea bottom which can readily be obtained with very little effort on the part of the fishes.

The progress of large bodies of salmon in the sea, judged by the catches in nets at different stations, is said to be four or five miles a day. They only travel in the daytime; no salmon are taken in the nets at night.

After entering the river, these conditions are changed for then the salmon travel mostly by night.

Previous to entering the pure fresh water they remain for some time in the estuaries, moving in and out on the tides and becoming gradually acclimatized to the change from salt to fresh water.

A considerable portion of the salmon that spawn before the rivers freeze return to the sea the same autumn, but a large number winter in the rivers and come down stream in the spring as kelts or “slinks.”

The French Canadians call these fish lingards—a corruption of “long gars.”

The kelts that descend the rivers in the autumn are dark in colour and slimy, whereas those that leave in the spring, having molted, are bright fish. This, at least, is the present day theory.

It is supposed that the grilse are four or five years old and that their rate of growth after that period is from four to six pounds a year.

A salmon was caught at West Baldwins half a mile from Channel Head, Newfoundland, by Louis Sheaves on June 5, 1919, with a silver tag attached to its dorsal fin marked Al 124. The fish when caught measured 40 inches in length, 23 inches in girth and weighed 26 pounds. R. Mosdell, the station master at Port aux Basques, obtained the fin tag and submitted it to the Game and Inland Fisheries Board for inquiry as to where the fish had been liberated.

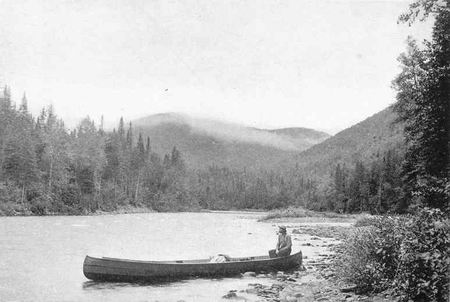

DUTHIES POOL

On July 15 he received a message from the Game Board stating that the fish was liberated from the salmon hatchery at Margarie, Nova Scotia, November, 1917; at that time it measured 34 inches in length and weighed 12 pounds.

This dislodges the theory that salmon always frequent the same water yearly, and also shows a remarkable growth within the given period.

This fish in nineteen months grew in length 6 inches, being an average of almost an inch every three months, and gained an average of three-quarters of a pound in weight per month for the same period.

THE AGE OF SALMON

According to Malloch it is easy not only to tell the age of an Atlantic salmon by its scales but also to follow its journeyings and occupations through life.

As the rings on a cross-section of a tree show the tree’s yearly growth, so do the rings on a salmon’s scale determine the age of a salmon.

The scales of a parr hatched in March when a year old have sixteen rings, and thirty-two rings can be counted after the expiration of another twelve months.

Two months or so later the parr becomes a smolt and goes down to the sea and may return the following May or June as a grilse with fifty-two rings, more or less.

If the rings on a fish’s scales number less than fifty-eight it is a grilse, if more than that number show it is a salmon.

All the grilse and salmon that enter a river are supposed to spawn and those that remain long in fresh water have the edges of their scales broken off. When the kelt-grilse and the kelt-salmon return to the sea and begin to feed, a ring forms around these broken parts and these rings increase in number according to the time the fish remain in the sea.

In the Grand Cascapedia River a grilse is seldom seen or taken. This may account for the great average size of the salmon in that river. These fish may pass their grilse term of life in the sea, where, with good food and without the fatigue of spawning, they grow in weight accordingly, and enter the river later on as full-fledged salmon. Few salmon are taken in the Grand Cascapedia under 20 pounds in weight, and it was there that Dr. S. Weir Mitchell took in 1896 40 salmon that averaged 28 pounds.

In order to determine the time the salmon remain in the sea it is necessary to count the rings from the broken or uneven lines outwards. No rings are formed on the scales in fresh water.

The great majority of salmon are said to spawn but once although some spawn twice or more often.

It is claimed that salmon, during the period of their stay in a river and after having fulfilled their mission, lose twenty-five per cent of their weight.

The very large salmon, those from forty to fifty pounds, are cock-fish, generally old bachelors, gourmets and gourmands that have remained in the sea where the food is good and plentiful rather than undertake the up-stream struggle with perhaps little or no food, and with domestic troubles awaiting them at their journey’s end.

For example, the 61 pound cock-salmon taken in the Tay in Scotland on July 13th, 1902, proved by its scales to be 7 years and 2 months old, and the scales also showed that it was this salmon’s first return from the sea.

It is claimed that as far as rivers are concerned the life of an Atlantic salmon is 8 years. No fish have been taken of a greater age.

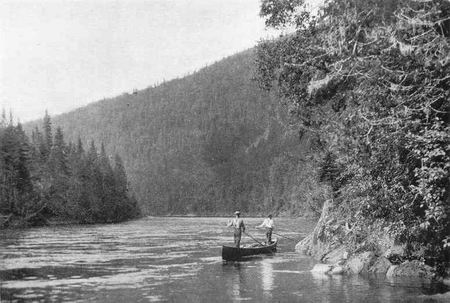

JOE MARTIN POOL

MODERN SALMON FISHING

By modern salmon fishing I mean the present-day form of fishing from a canoe on Canadian rivers, for in Scotland, where a man must wade or fish from the bank and is often obliged to cast a very long line, the modern light rods would be of poor service.

In canoe fishing the sport is made easy, for after a fish is hooked the canoe may be moved about and you are quickly placed below your fish, or should the fish take down stream you may follow him on his mad career.

In this form of fishing you seldom have to cast a fly more than twenty-five yards. The length and weight of a rod depend on the distance it is necessary to cast a fly, for after hooking a fish it is a very easy matter to end the struggle in short order if you Understand handling fish, for a fresh run salmon, though active, is not a strong fighting fish for its weight.

Some of the old-time anglers still use the English wooden rods of sixteen feet or more in length, for they maintain that they are superior to the modern light split bamboo grilse rod. Their theory is that the latter is too quick in action and loses many striking fish, which it should not do if the rod is handled with the light hand that it is not possible to employ with a heavy rod. I find the green-heart rod is superior in a strong wind, for it has more power.

The wooden rod, though more brutal when you first give the fish the butt, is not nearly so killing, for every fibre in the bamboo is alive and at work all the time.

The modern split bamboo grilse rods now in use are fourteen feet, more or less, in length and are easy to handle for they are well balanced and weigh from 16 to 24 ounces.

My advice to a beginner using these rods is to banish the idea that the salmon rod is a two-handed rod, and always to bear in mind the fact that the right arm and the rod are as one. No amount of energy applied to the rod by the left hand will communicate itself to the line. The left hand is employed as a help in holding the rod, in fact is simply a rod-rest.

By grasping the rod firmly with the right hand at the upper end of the cork handle, with the thumb along the rod, the energy of the right arm is communicated to the rod. You cannot use the full spring of the rod unless it is firmly held. This may not be necessary for a short cast but for a long line it is imperative.

After lifting the line from the water for the back cast a flip of the left thumb to the butt at the right moment is all that is necessary, the forward cast being made with the right hand only.

ANGLING FOR SALMON WITH A “DOPED” FLY

I have for years been a great believer in the acute smelling powers of fish. These powers I have often tested when seafishing.

If on a still day you see the dorsal fin of a leisurely swimming shark on the surface of the ocean, you may always inspire the shark with new life by pouring fresh fish blood into the sea. The shark will at once become alert and begin to hunt the blood-scent until he finally discovers its source.

Then again, when anchored and fishing for bonefish, after having distributed the crab-meat chum, you will often see a school of bonefish hunting the smell of the chum as a pack of hounds hunt the cold scent of a fox, quartering to the right and to the left until they eventually hit the line and find what they are looking for.

Knowing that trappers in the northern woods lead their prey to their baited traps with “charm-oil,” I conceived the idea that fish might be enticed in a like manner.

This was difficult in seafishing as the friction caused by trolling a bait through the water destroyed the odor of the “charm-oil,” but in fly-fishing I found it quite simple.

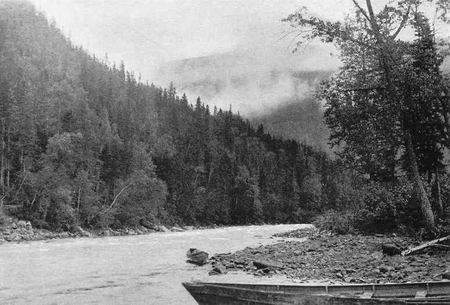

INDIAN FALLS RAPIDS.

My first attempt was when fishing on a salmon river in Canada. The river was low and the water quite clear. I had been fishing over a salmon of fair size that could readily be seen lying on the bottom close to a large stone.

After trying different flies as well as different sizes of flies with no result, I handed the rod to my canoeman, an old and very experienced fisherman, and told him to have a try. He used all his powers of persuasion to entice the fish but with no success.

As he handed me my rod I said: “Now I shall show you how to take that fish.”

I anointed the fly he had been fishing with by placing a drop of “charm-oil” on the hackle of the fly. On my second cast I rose, hooked, and landed a 24-pound salmon. This was not chance for it happened on several occasions in a like manner, rising fish that would not look at an “un-doped” fly.

The last day on the river that season found me, after three days of heavy rain, stormbound at a camp up stream, with all the experts insisting that no fishing was possible.

The water had risen seven inches since eight o’clock in the morning, and three feet since the rain began, and it was still rising at one when we started down stream.

A heavy fog overhung the river and the water was of the colour and consistency of pea-soup, a combination of every adverse condition possible for sport.

I proposed stopping at a choice pool on the way down stream, for, I said, I wished

to take a few fish home.

I was laughed at by the canoemen but, being more of a fisherman than an angler and having no prejudices, I insisted.

When we reached the pool we found the water very high and running strong. I could hear the small stones rolling along the bottom of the pool, and the partly submerged branches of the bushes on the banks were dancing back and forth as the current swept by.

CHARLIE VALLEY

The canoeman said: “There ain’t no fish in this pool, don’t you hear the stones a-rolling? I replied that they must be somewhere about the pool as I saw no salmon on the bank and that fish were not known to climb trees.

The killig was dropped close to the bushes at the edge of the pool and, casting a well “doped” fly down stream, I rose, hooked, and landed three salmon of 12, 26 and 35 pounds, the only fish taken on the river that day.

The canoe could not be moved about owing to the rapid current and, as I was fishing with a light grilse rod, it was no easy matter to handle the two heavy fish.

Later on I discovered the following in “The Northwest Coast,” a book by James C. Swan published in 1857. Writing of salmon fishing in Shoal Water Bay, Washington Territory, he says: “When the fish were shy or the Indians unsuccessful they would rub their hooks with the root of wild celery which has a very aromatic smell and is believed by the Indians to be very grateful to the salmon and sure to attract them. I have also seen the Indians at Chenook rub the celery root into their nets for the same purpose though I have never tried its effects and have some doubts about its value.”

Click

here to continue to the next chapter of

Some Fish and Some Fishing