| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2018 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

CHAPTER 33 Seeing

that the door did not open, the driver gave it a violent kick. It fell

and he

entered the room saying in his usual oily way, "Good boys! You bray

very

well. I recognize your voices and here I am to take you away." At these

words the two little donkeys became quiet. They lowered their heads and

ears

and put their tails between their legs. At first

the driver patted them and smoothed their hair. After that he pulled

out some

leather straps and bridled them both. When he had curried them so that

they

looked like two looking-glasses, he took them to the square in the hope

of

selling them and making a good trade. The

purchasers soon made their appearance. Lamp Wick was bought by a farmer

whose

donkey had died the day before from overwork. Pinocchio was bought by

the

director of a company of clowns and circus men, so that he could be

taught to

do tricks and capers. And now,

my little readers, do you understand what the trade of the driver was?

That

monster, who had a face of milk and honey, went from time to time

through the

world with a carriage and collected, by promises, all the naughty boys

that

were tired of books and school. After he had filled his carriage he

took them

to the Country of Playthings, where they passed all the time in playing

and

having fun. When these poor deluded boys had played for a certain time

they

turned into donkeys, which he led away and sold in the town. By this

means he

had become very rich, — in fact a millionaire. What

happened finally to Lamp Wick I do not know. I know, however, that

Pinocchio

led a very hard and weary life. When he was taken to a stall his new

master

emptied some straw into the manger; but Pinocchio, after he had eaten a

mouthful, spat it out. Then the master, scolding, gave him some hay;

but that

did not please him. "Ah!

You do not like hay?" cried the master, in anger. "I will teach you

better manners." He then

took a whip and gave the donkey a crack on the legs. Pinocchio, in

great pain,

gave a long bray, as if to say, "Y-a, y-a, I cannot digest straw." "Then

eat hay," replied the master, who understood the donkey dialect very

well. "Y-a, y-a.

Hay gives me a headache." "You

mean that a donkey like you wants to eat chicken and capon?" added the

master; and he gave him another lash with the whip. At the

second rebuke Pinocchio, for prudence' sake, kept quiet and said

nothing.

Meanwhile the stall was closed and Pinocchio remained alone; and

because he had

not eaten anything for hours he grew very hungry. He opened his mouth

and was

surprised to find that it was so large. He

finally looked around, and not finding anything in the manger but hay,

took a

little. After having chewed it well he winked his eye and said: "This

hay

is not bad at all. But how much better off I should have been if I had

not run

away! Now I should be eating something nice instead of this dry stuff.

Oh me!

oh me! oh me!" When he

awoke the next morning he looked into his manger, but he had eaten all

the hay.

Then he took a mouthful of straw and tried that. It did not taste so

good as rice alla Milanese or macaroni

alla Napolitana; but he managed

to eat it. "Oh me!" he said, while he ate; "oh, if I could only

warn other boys of my misfortune, how happy I should be! Oh me! oh me!"

"Oh

me!" repeated the master, entering the stall at that moment. "Do you

think, donkey, that I have bought you just to watch you eat and drink?

Oh no! I

bought you so that you could earn some money for me. Come with me and I

will

teach you how to jump and bow; and then you must dance the waltz and

the polka

and stand up on your hind legs." Poor Pinocchio! He had a hard struggle. It took him three months to learn these things and he received many a blow from his teacher.  The day finally came when the master could announce to the public a most extraordinary spectacle. Posters of all colors were pasted everywhere and they read thus:

That

night, as you can easily imagine, there was not a seat to be had in the

house,

and all the standing room was taken an hour before the show began. The

whole

theater swarmed with little children and babies of all ages, who were

wild to

see the famous donkey Pinocchio dance. When the

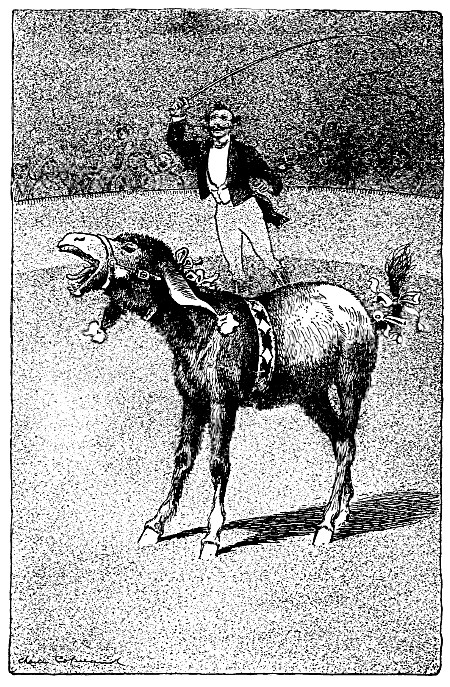

first part of the performance was over the master, in an evening coat,

with

white trousers and little black boots, presented himself to the public

and,

after making a profound bow, shouted: The

master then presented him to the public with these words: Pinocchio,

obeying, fell on his knees and stayed there until the master cracked

his whip

and cried, "Now walk." Then the donkey stood up on his four feet and

began to walk around in a circle. "Now

trot." And Pinocchio began to trot. "Gallop."

And Pinocchio began to gallop. "Now

full speed." And Pinocchio ran as hard as he could. While he was

running

the master, raising a pistol, fired twice. At that

sound the donkey, pretending to be hit, fell flat on the floor as if he

were

dead. Raising

himself in the midst of a shower of applause which could be heard for

miles,

Pinocchio looked at the audience. As he looked he saw a beautiful lady

wearing

around her neck a large gold chain from which hung a medallion. On the

medallion

was engraved the picture of a marionette. "That

is my picture! That lady is the Fairy!" said Pinocchio to himself,

recognizing her instantly. He tried to cry, "Oh, my Fairy! oh, my

Fairy!" But instead of these words there came from his throat such a

braying that everybody laughed, especially the boys. Then the

master, in order to teach him better manners than to bray at the

audience, gave

him a blow on the nose with the handle of the whip. The poor donkey

licked his

nose at least a dozen times because it pained him so. But what was his

desperation when, turning around a second time and looking toward the

Fairy, he

found that she had disappeared. He thought he should die. His eyes filled with tears and he began to cry. No one, however, saw it, not even the master, who, cracking his whip, cried, "Now show the people how well you can dance."  Pinocchio

tried two or three times; but every time he came before the audience

his feet

slipped from under him. Finally, in a great effort, his hind foot

slipped so

badly that he fell to the floor in a heap. When he got up he was so

lame that

he could hardly walk and had to be taken to his stall. "Bring

out Pinocchio! We want the donkey! Bring him out!" cried the boys in

the

theater, who had seen the pitiful sight. But the donkey could not be

seen any

more that night. The next morning the veterinary, that is, the doctor

of

beasts, when he saw the poor donkey, declared that he would be lame all

through

life. Then the master said to the stable boy: "What can we do with a

lame

donkey? To keep him would be feeding one more mouth for nothing. Take

him to

the square and sell him." When

they arrived at the square they immediately found a buyer who asked the

price. "Four

dollars," replied the stable boy. "I

will give you twenty-five cents for him. Do not think that I buy him

for

hauling. Oh, no; I want him to skin. I see that his skin is very hard,

— just

the thing for a drum or a tambourine." Just

imagine how Pinocchio felt when he heard that he was worth only

twenty-five

cents! Then, too, to be used as a drum to be beaten upon all the time! The buyer

had hardly paid for him when he led him to the top of a cliff on the

shore of

the sea, and, tying a heavy stone around his neck and binding his feet

together

with cords, threw him over the edge. The donkey, with this heavy weight around his neck, sank to the bottom immediately. The buyer who had one end of the rope in his hands, sat down and waited awhile, so that the donkey would have time to drown.

|