IX

The Royal Game

FOR several days after the pig episode I refused to start

for Port Lafayette in Millington's automobile, although he used to lean over

the fence and beg me almost tearfully, but one fine morning he came over, and

he looked so haggard and care worn that I took pity on him.

"John," he said, as he led me to his garage, which

was on the back of his lot, "I am sure this automobile of mine is

bewitched. I cannot think of anything else that would make it behave as an

automobile in good health should, and I give you my word of honour that it is

acting in perfect rhythm, never slipping a cog nor missing fire. Of course,

with the machine behaving in that unaccountable manner, I would not dare to

start for Port Lafayette, but I want to run you around to the Country Club. You

ought to be in our Country Club, and I want you to see it, and I want you to

tell me what you think about this automobile of mine. I can't understand

it!"

I have often noticed three things: I have noticed that a boy

is never really happy until he owns a dog; I have noticed that a flat-dweller

is never content until he owns a phonograph; but above all I have noticed that

the commuter — the man that lives in the sweet-scented, tree-embowered suburbs

is restless and uneasy until he joins the Country Club. So I accepted

Millington's invitation.

We ran out of his yard and half a block up the street,

Millington listening carefully all the while, and we could not hear a sound of

distress in any part of the automobile. Millington stopped the car and got out.

"I am going to walk to the Club," he said. "I

won't trust myself in that car. As for you, as it was entirely for your sake I

proposed this little run to the Club, I am going to put the machine in your

charge, and you are to run it around the block until it resumes its normal bad

condition. From what I know of you and the remarks you have made while I have

tried to repair the engine, I believe you will soon have it making all sorts of

noises, and," he added, "perhaps it will be making a noise it never

made before."

Then he showed me how to start, and what to touch if a tree

or telephone post got in my way, and then he went on to the Country Club.

I was much touched by this evidence of Millington's faith in

my ability to bring out the bad points of his automobile, and as soon as he

disappeared I set to work, and I had hardly gone twice around the block before

I had it knocking more loudly than ever I had heard it knock. But I was

resolved to show Millington that his trust was not mis placed, and I ran the

nose of the machine into a tree, threw on the high speed suddenly until I heard

a grinding noise that told me the gears were stripped. Then I left the car

there and walked on to the Country Club.

A Country Club is an institution conducted for the purpose

of securing as many new members as possible, in order that their initiation

fees may pay for the upkeep of the golf green. Aside from this, the object of

the club is to enable the men that mow the grass to make an honest living by

selling the golf balls they find while mowing the grass.

The Membership Committee, on which Millington served, is a

small body of men whose duty it is to learn, as soon as possible, who that new

man is that moved into Billing's house, and to get twenty dollars in initiation

fees from him, before he has spent all his money for mosquito screens.

When Millington said to me, in the way members of Country

Clubs have, "You ought to be in our Country Club," I was tickled. I

did not know then that Millington was on the membership committee, and his

willing ness to admit me to fellowship seemed to show that I had been promptly

recognized as a desirable citizen of Westcote; a man worth knowing; one of the

inner circle of desirables. What more fully convinced me was the eager ness of

Mr. Rolfs.

"We must have you in," said Rolfs. "I have

been speaking to several of the members about you, and they are all

enthusiastic about taking you in. Of course, our green is a little ragged just

now, but when we get your mon — when — of course, the green is a little ragged

just now, but we expect to have it trimmed soon, very soon."

Isobel was delighted when I told her I contemplated joining

the Country Club. She said it would do me all the good in the world to play a

game of golf now and then, and when I mentioned that I thought of taking family

membership, which would admit her to all the club privileges, she was more than

pleased. So were Mr. Rolfs and Mr. Millington. I forget how many more dollars a

family membership cost. They shook hands with me warmly, and Millington said

something to Rolfs about their now being able to dump another load or two of

sand on the bunker at the sixth hole. They also said the ladies would be

delighted. Many, they said, had asked them why Isobel had not joined.

Then they mentioned earnestly that the initiation fee and

the first year's dues were payable immediately. They even offered to send in my

check for the amount with my membership application.

I had never played golf, but Millington said he would lend

me an excellent book on the game, written by one of the great players, and

Rolfs offered to pick me out a set of clubs. He was enthusiastic when we went

to the shop where clubs were sold, and I must say he did not allow the clerk to

foist off on me any old-fashioned, shop-worn clubs. He said with pride, as we

left the shop, that, so far as he knew, every club I had secured was absolutely

new in model, and that not one club in the lot was of a kind ever seen on the

Westcote course before. Some he said, he was sure had never been seen on any

course anywhere.

He said my putter would create great excitement when it

appeared on the course. I must give him credit for being right. The putter was,

perhaps, too much like a brass sledge-hammer to be graceful, and I found later

that it worked much better as a croquet mallet than as a tool for putting a

golf ball into a hole, but it was fine advertisement for a new member. Members

who might never have noticed me at all began to speak of me immediately. They

referred to me as "that fellow that Rolfs got to buy the idiotic

putter."

The golf course at our Westcote Country Club is one of the

best I have ever seen. It is almost free from those irregularities of ground

that make so many golf courses fretful. In selecting the ground the Committee

had in mind, I think, a billiard table, but as it was impossible to secure a

sufficiently large plot of ground as level as that near Westcote, they secured

the most level they could and then went over it with a steam grader. The

envious members of the Oakland Club speak of it as the Westcote Croquet

Grounds.

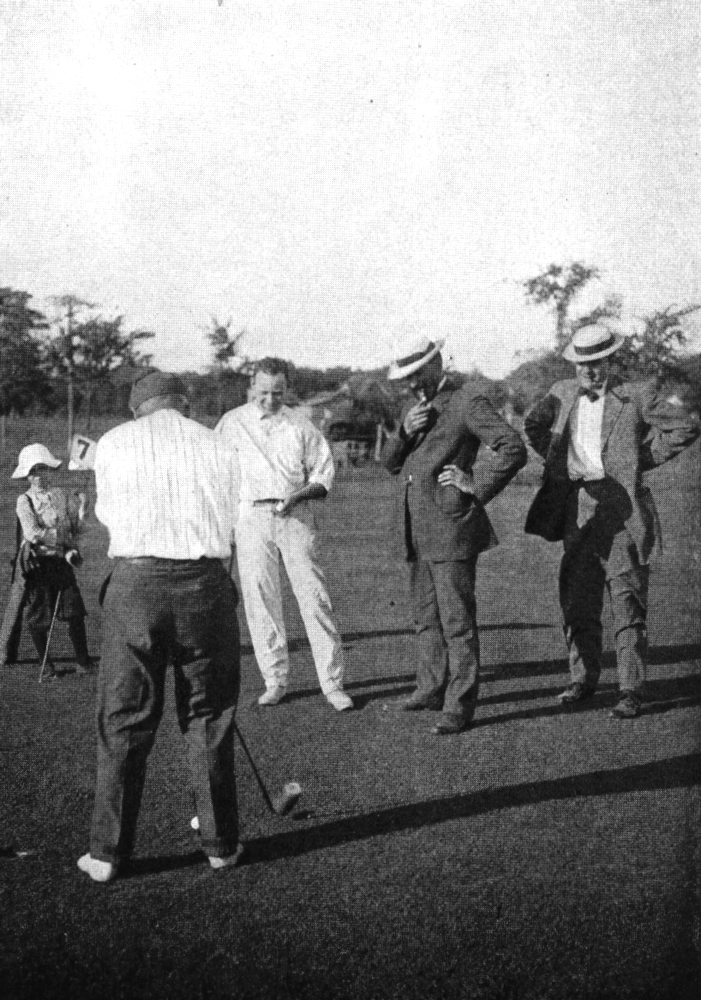

The first day I appeared at the club I saw that golf was

indeed a difficult game, particularly after Mr. Millington had explained how it

was worked. He began by remarking that, of course, I could not expect to do

much with "that bunch of crazy scrap iron" that being the manner in

which he referred to the up-to-date clubs Rolfs had selected for me and that no

man who knew anything about golf ever used the red-white-and-pink polka-dot

balls, which were the kind Rolfs had advised me to buy. Then he looked through

my clubs scornfully and selected my putter.

"Usually," he said ironically, "we begin with

a driver, and drive the ball as far as we can from this place, which is called

the driving green, but I think this tool, in your hands, will do as well as

anything else in your collection of kitchen cutlery. What do you call this

tool, anyway?"

I looked at the label on the handle and read it. I told

Millington it was a putter, but he would not believe me. I showed him the

label, which said quite plainly "putter," but he was still skeptical.

He did not deny positively that it was a putter; he merely said, "Well, if

this instrument of torture is a putter, I'll eat it."

Mr. Millington then made a little mound of sand which he

took from the green sand box, and set one of my golf balls on top of the mound.

This, I soon learned, is called "teeing" the ball.

"Now," said Mr. Millington, "I will explain

the game. Wlien the ball is teed as you see it here, you take the club and hit

the ball so it will travel low and straight through the air as far as possible

toward that red flag you see yonder. The ball will alight on the fair green.

You follow it, and hit it again, and it should then alight fairly and squarely

on the putting-green. You then follow it, take the pole that bears the flag out

of the hole you will find there, and gently knock your ball into the hole. That

is all there is to the game."

"But what shall I do," I asked, "if my first

knock at the ball carries it beyond the flag?"

Mr. Millington glanced at the patent putter I held in my

hand, and sighed.

"Excuse me," he said, "but the rules of the

game permit one to grasp the club with both hands."

"He merely said, "Well, if this instrument of

torture is a putter, I'll eat it"

"I guess," I said airily, "until I get the

swing of it I will grasp the club with one hand. I only use one hand in playing

croquet."

"In that case," said Mr. Millington, "if you

knock the ball past the flag I will eat the flag. I will also eat the ball.

Also the thing you call a putter. If you knock the ball half way to the flag, I

will eat all the grass on this golf course."

"Be careful, Millington," I warned him. "You

may have to eat that grass. Now, stand back and let me have a fair whack at the

ball."

With that I swung the putter around my head two or three

times, to gather the necessary impetus, and then hit the ball a terrible whack.

I put my full strength into the blow r , for I wanted to show Millington that I

had the making of a golfer in me; but when my putter ceased revolving around me

Millington seemed unimpressed. I put my hand above my eyes and gazed into the

far distance, hoping to catch sight of the ball when it alighted. But I did not

see it.

"Millington," I said, "did you see where that

ball went?"

"I did," he said, turning to the left. "It

went over there, into that tall grass. It is a lost ball. Every ball that goes

into that tall grass is gone forever. I have never known any one to recover a

ball that fell in that tall grass."

Then he stepped proudly to the sand-box and made another

tee.

"Hand me a ball," he said, "and I will show

you the proper way to hit it."

I gave him a ball and he placed it carefully on the tee.

Then he grasped his driver in both hands, snuggled the head of it up to the

ball lovingly, drew back the club and struck the ball. I was not quick enough

to see the ball go, but Millington was.

"Fine!" he exclaimed. "I sliced it a little,

but I must have got good distance. I must have driven that ball two hundred

yards."

"But where did it go?" I asked.

"Well," said Millington, "I did slice it a

little. It went off there to the right, into that tall grass. It is a lost

ball. I have never known any one to recover a ball that fell in that tall

grass. But let me have another ball and I will show you —"

I told Millington I guessed I would lose a couple of balls

myself while I had a few left, if it was not against the rules. He said no, a

player could lose as many as he wished; in fact many players lost more than

they wished.

"When my putter ceased revolving around me Millington

seemed unimpressed"

I found this to be so. We played around the nine holes and I

made a score of 114, and Millington was delighted. He said it was a splendid

score to turn in to the handicapping committee, and that he wished he could

make a large, safe score like that. He said no one in the club had ever made

more than 110 and that the average was about 45. Then he said I need not lose

hope, for at any rate I had not lost a ball at every stroke. He said he had

imagined when he saw me play that I would lose a ball at every stroke, for my

style of playing — my "form" he called it — was the sort that ought

to lose me one ball for every stroke.

When I reached home I found Isobel awaiting me, and, without

thinking, I blurted out that I had lost thirty-eight golf balls. Her mouth

hardened.

"John," she said, "I have been talking with

Mrs. Rolfs and Mrs. Millington about this game of golf, and what they say has

given me an entirely different opinion of it. When I advised you to take it up

I had no idea it was a gambling game, but they both tell me the matches are

often played for a stake of balls. Mrs. Rolfs says her husband has accumulated

eighty balls in this way, and Mrs. Millington says her husband has laid up a

store of over fifty. And now, when you come home and tell me you have lost, in one

afternoon, thirty-eight golf balls, at a cost of fifty cents each, I feel that

golf is a wicked, sinful game. I do not want to seem severe, but I do not

approve of gambling, and if you continue to lose so many golf balls you will

have to give up the game."

|