| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2007 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER III

NUBRA In order

to visit Lower Nubra and

return to Leh we were obliged to cross the great fords of the Shayok at

the

most dangerous season of the year. This

transit had been the bugbear of the journey ever since news reached us

of the

destruction of the Sati scow. Mr.

Redslob questioned every man we met on the subject, solemn and noisy

conclaves

were held upon it round the camp-fires, it was said that the 'European

woman'

and her 'spider-legged horse' could never get across, and for days

before we

reached the stream, the chupas,

or government water-guides, made

nightly reports to the village headmen of the state of the waters,

which were

steadily rising, the final verdict being that they were only just

practicable

for strong horses. To delay till the waters fell was impossible. Mr. Redslob had engagements in Leh, and I

was already somewhat late for the passage of the lofty passes between

Tibet and

British India before the winter, so we decided on crossing with every

precaution which experience could suggest. At Lagshung, the evening before, the Tibetans made prayers and offerings for a day cloudy enough to keep the water down, but in the morning from a cloudless sky a scintillating sun blazed down like a magnesium light, and every glacier and snowfield sent its tribute torrent to the Shayok. In crossing a stretch of white sand the solar heat was so fierce that our European skins were blistered through our clothing. We halted at Lagshung, at the house of a friendly zemindar, who pressed upon me the loan of a big Yarkand horse for the ford, a kindness which nearly proved fatal; and then by shingle paths through lacerating thickets of the horrid Hippophaë rhamnoides, we reached a chod-ten on the shingly bank of the river, where the Tibetans renewed their prayers and offerings, and the final orders for the crossing were issued. We had twelve horses, carrying only quarter loads each, all led; the servants were mounted, 'water-guides' with ten-foot poles sounded the river ahead, one led Mr. Redslob's horse (the rider being bare-legged) in front of mine with a long rope, and two more led mine, while the gopas of three villages and the zemindar steadied my horse against the stream. The water-guides only wore girdles, and with elf-locks and pig-tails streaming from their heads, and their uncouth yells and wild gesticulations, they looked true river-demons.  A Lama The Shayok

presented an expanse of

eight branches and a main stream, divided by shallows and shingle

banks, the

whole a mile and a half in width. On

the brink the chupas

made us all drink good draughts of the turbid river

water, 'to prevent giddiness,' they said, and they added that I must

not think

them rude if they dashed water at my face frequently with the same

object. Hassan Khan, and Mando, who was

livid with

fright, wore dark-green goggles, that they might not see the rapids. In the second branch the water reached the

horses' bodies, and my animal tottered and swerved.

There were bursts of wild laughter, not merriment but

excitement,

accompanied by yells as the streams grew fiercer, a loud chorus of Kabadar! Sharbaz! ('Caution!'

'Well

done!') was yelled to encourage the horses, and the boom and hiss of

the Shayok

made a wild accompaniment. Gyalpo, for

whose legs of steel I longed, frolicked as usual, making mirthful

lunges at his

leader when the pair halted. Hassan

Khan, in the deepest branch, shakily said to me, 'I not afraid, Mem

Sahib.'

During the hour spent in crossing the eight branches, I thought that

the risk

had been exaggerated, and that giddiness was the chief peril. But when we halted, cold and dripping, on the shingle bank of the main stream I changed my mind. A deep, fierce, swirling rapid, with a calmer depth below its farther bank, and fully a quarter of a mile wide, was yet to be crossed. The business was serious. All the chupas went up and down, sounding, long before they found a possible passage. All loads were raised higher, the men roped their soaked clothing on their shoulders, water was dashed repeatedly at our faces, girths were tightened, and then, with shouts and yells, the whole caravan plunged into deep water, strong, and almost ice-cold. Half an hour was spent in that devious ford, without any apparent progress, for in the dizzy swirl the horses simply seemed treading the water backwards. Louder grew the yells as the torrent raged more hoarsely, the chorus of kabadar grew frantic, the water was up to the men's armpits and the seat of my saddle, my horse tottered and swerved several times, the nearing shore presented an abrupt bank underscooped by the stream. There was a deeper plunge, an encouraging shout, and Mr. Redslob's strong horse leapt the bank. The gopas encouraged mine; he made a desperate effort, but fell short and rolled over backwards into the Shayok with his rider under him. A struggle, a moment of suffocation, and I was extricated by strong arms, to be knocked down again by the rush of the water, to be again dragged up and hauled and hoisted up the crumbling bank. I escaped with a broken rib and some severe bruises, but the horse was drowned. Mr. Redslob, who had thought that my life could not be saved, and the Tibetans were so distressed by the accident that I made very light of it, and only took one day of rest. The following morning some men and animals were carried away, and afterwards the ford was impassable for a fortnight. Such risks are among the amenities of the great trade route from India into Central Asia!  Three Gopas The Lower

Nubra valley is wilder and

narrower than the Upper, its apricot orchards more luxuriant, its

wolf-haunted hippophaë

and tamarisk thickets more

dense. Its villages are always close to

ravines, the mouths of which are filled with chod-tens, manis,

prayer-wheels, and religious buildings. Access

to them is usually up the stony beds of streams

over-arched by

apricots. The camping- grounds are

apricot orchards. The apricot foliage

is rich, and the fruit small but delicious. The

largest fruit tree I saw measured nine feet six inches

in girth six

feet from the ground. Strangers are

welcome to eat as much of the fruit as they please, provided that they

return

the stones to the proprietor. It is

true that Nubra exports dried apricots, and the women were splitting

and drying

the fruit on every house roof, but the special raison

d'etre of the tree is the clear, white, fragrant, and highly

illuminating oil made from the kernels by the simple process of

crushing them

between two stones. In every gonpo

temple a silver bowl holding from four to six gallons is replenished

annually

with this almond-scented oil for the ever-burning light before the

shrine of

Buddha. It is used for lamps, and very

largely in cookery. Children, instead

of being washed, are rubbed daily with it, and on being weaned at the

age of

four or five, are fed for some time, or rather crammed, with balls of

barley-meal made into a paste with it. At Hundar,

a superbly situated

village, which we visited twice, we were received at the house of

Gergan the

monk, who had accompanied us throughout. He

is a zemindar,

and the large house in which he made us welcome

stands in his own patrimony. Everything

was prepared for us. The mud floors

were swept, cotton quilts were laid down on the balconies, blue

cornflowers and

marigolds, cultivated for religious ornament, were in all the rooms,

and the

women were in gala dress and loaded with coarse jewellery.

Right hearty was the welcome. Mr.

Redslob loved, and therefore was loved. The

Tibetans to him were not 'natives,' but

brothers. He drew the best out of

them. Their superstitions and beliefs

were not to him 'rubbish,' but subjects for minute investigation and

study. His courtesy to all was frank

and dignified. In his dealings he was

scrupulously just. He was intensely

interested in their interests. His

Tibetan scholarship and knowledge of Tibetan sacred literature gave him

almost

the standing of an abbot among them, and his medical skill and

knowledge,

joyfully used for their benefit on former occasions, had won their

regard. So at Hundar, as everywhere else,

the elders

came out to meet us and cut the apricot branches away on our road, and

the

silver horns of the gonpo

above brayed a dissonant

welcome. Along the Indus valley the

servants of Englishmen beat the Tibetans, in the Shayok and Nubra

valleys the

Yarkand traders beat and cheat them, and the women are shy with

strangers, but

at Hundar they were frank and friendly with me, saying, as many others

had

said, 'We will trust any one who comes with the missionary.' Gergan's

home was typical of the

dwellings of the richer cultivators and landholders.

It was a large, rambling, three-storeyed house, the lower

part of

stone, the upper of huge sun-dried bricks. It

was adorned with projecting windows and brown wooden

balconies. Fuel—the dried excreta of animals—is

too scarce to be used for any but cooking purposes, and on these

balconies in

the severe cold of winter the people sit to imbibe the warm sunshine. The rooms were large, ceiled with peeled

poplar rods, and floored with split white pebbles set in clay. There was a temple on the roof, and in it,

on a platform, were life-size images of Buddha, seated in eternal calm,

with his

downcast eyes and mild Hindu face, the thousand-armed Chan-ra-zigs (the

great

Mercy), Jam-pal-yangs (the Wisdom), and Chag-na-dorje (the Justice). In front on a table or altar were seven

small lamps, burning apricot oil, and twenty small brass cups,

containing

minute offerings of rice and other things, changed daily.

There were prayer-wheels, cymbals, horns and

drums, and a prayer-cylinder six feet high, which it took the strength

of two

men to turn. On a shelf immediately

below the idols were the brazen sceptre, bell, and thunderbolt, a brass

lotus

blossom, and the spouted brass flagon decorated with peacocks'

feathers, which

is used at baptisms, and for pouring holy water upon the hands at

festivals. In houses in which there is

not a roof temple the best room is set apart for religious use and for

these

divinities, which are always surrounded with musical instruments and

symbols of

power, and receive worship and offerings daily, Tibetan Buddhism being

a

religion of the family and household. In

his family temple Gergan offered gifts and thanks for

the

deliverances of the journey. He had

been assisting Mr. Redslob for two years in the translation of the New

Testament, and had wept over the love and sufferings of our Lord Jesus

Christ. He had even desired that his son

should

receive baptism and be brought up as a Christian, but for himself he

'could not

break with custom and his ancestral creed.' In the

usual living-room of the

family a platform, raised only a few inches, ran partly round the wall. In the middle of the floor there was a clay

fireplace, with a prayer-wheel and some clay and brass cooking pots

upon

it. A few shelves, fire-bars for

roasting barley, a wooden churn, and some spinning arrangements were

the

furniture. A number of small dark rooms

used for sleeping and storage opened from this, and above were the

balconies

and reception rooms. Wooden posts

supported the roofs, and these were wreathed with lucerne, the

firstfruits of

the field. Narrow, steep staircases in

all Tibetan houses lead to the family rooms. In

winter the people live below, alongside of the animals

and

fodder. In summer they sleep in loosely

built booths of poplar branches on the roof. Gergan's

roof was covered, like others at the time, to the

depth of two

feet, with hay, i.e. grass and lucerne, which are wound into long

ropes,

experience having taught the Tibetans that their scarce fodder is best

preserved thus from breakage and waste. I

bought hay by the yard for Gyalpo. Our food

in this hospitable house

was simple: apricots, fresh, or dried

and stewed with honey; zho's

milk, curds and cheese, sour cream, peas, beans, balls of barley dough,

barley

porridge, and 'broth of abominable things.' Chang, a

dirty-looking

beer made from barley, was offered with each meal, and tea frequently,

but I

took my own 'on the sly.' I have

mentioned a churn as part of the 'plenishings' of the living-room. In Tibet the churn is used for making

tea! I give the recipe.

'For six persons. Boil a

teacupful of tea in three pints of water for ten minutes

with a heaped dessert- spoonful of soda. Put

the infusion into the churn with one pound of butter

and a small

tablespoonful of salt. Churn until as

thick as cream.' Tea made after this

fashion holds the second place to chang in Tibetan affections. The butter according to our thinking is

always rancid, the mode of making it is uncleanly, and it always has a

rank

flavour from the goatskin in which it was kept. Its

value is enhanced by age. I saw skins of

it forty, fifty, and even sixty years old,

which were

very highly prized, and would only be opened at some special family

festival or

funeral. During the

three days of our visits

to Hundar both men and women wore their festival dresses, and

apparently

abandoned most of their ordinary occupations in our honour. The men were very anxious that I should be

'amused,' and made many grotesque suggestions on the subject. 'Why is the European woman always writing or

sewing?' they asked. 'Is she very poor,

or has she made a vow?' Visits to some

of the neighbouring monasteries were eventually proposed, and turned

out most

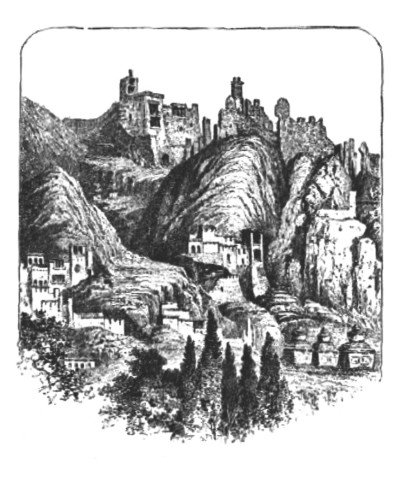

interesting. The monastery of Deskyid, to which we made a three days' expedition, is from its size and picturesque situation the most imposing in Nubra. Built on a majestic spur of rock rising on one side 2,000 feet perpendicularly from a torrent, the spur itself having an altitude of 11,000 feet, with red peaks, snow-capped, rising to a height of over 20,000 feet behind the vast irregular pile of red, white, and yellow temples, towers, storehouses, cloisters, galleries, and balconies, rising for 300 feet one above another, hanging over chasms, built out on wooden buttresses, and surmounted with flags, tridents, and yaks' tails, a central tower or keep dominating the whole, it is perhaps the most picturesque object I have ever seen, well worth the crossing of the Shayok fords, my painful accident, and much besides. It looks inaccessible, but in fact can be attained by rude zigzags of a thousand steps of rock, some natural, others roughly hewn, getting worse and worse as they rise higher, till the later zigzags suggest the difficulties of the ascent of the Great Pyramid. The day was fearfully hot, 99° in the shade, and the naked, shining surfaces of purple rock with a metallic lustre radiated heat. My 'gallant grey' took me up half-way—a great feat— and the Tibetans cheered and shouted 'Sharbaz!' ('Well done!') as he pluckily leapt up the great slippery rock ledges. After I dismounted, any number of willing hands hauled and helped me up the remaining horrible ascent, the rugged rudeness of which is quite indescribable. The inner entrance is a gateway decorated with a yak's head and many Buddhist emblems. High above, on a rude gallery, fifty monks were gathered with their musical instruments. As soon as the Kan-po or abbot, Punt-sog-sogman (the most perfect Merit), received us at the gate, the monkish orchestra broke forth in a tornado of sound of a most tremendous and thrilling quality, which was all but overwhelming, as the mountain echoes took up and prolonged the sound of fearful blasts on six-foot silver horns, the bellowing thunder of six-foot drums, the clash of cymbals, and the dissonance of a number of monster gongs. It was not music, but it was sublime. The blasts on the horns are to welcome a great personage, and such to the monks who despised his teaching was the devout and learned German missionary. Mr. Redslob explained that I had seen much of Buddhism in Ceylon and Japan, and wished to see their temples. So with our train of gopas, zemindar, peasants, and muleteers, we mounted to a corridor full of lamas in ragged red dresses, yellow girdles and yellow caps, where we were presented with plates of apricots, and the door of the lowest of the seven temples heavily grated backwards.  Some Instruments of Buddhist Worship The first

view, and indeed the whole

view of this temple of Wrath or

Justice,

was suggestive of a frightful Inferno,

with its rows of demon gods, hideous beyond Western conception, engaged

in

torturing writhing and bleeding specimens of humanity.

Demon masks of ancient lacquer hung from the

pillars, naked swords gleamed in motionless hands, and in a deep recess

whose

'darkness' was rendered 'visible' by one lamp, was that indescribable

horror

the executioner of the Lord of Hell, his many brandished arms holding

instruments of torture, and before him the bell, the thunderbolt and

sceptre,

the holy water, and the baptismal flagon. Our

joss-sticks fumed on the still air, monks waved

censers, and blasts

of dissonant music woke the semi-subterranean echoes.

In this temple of Justice the younger lamas spend some hours daily

in the supposed contemplation of the torments reserved for the unholy. In the highest temple, that of Peace, the

summer sunshine fell on Shakya Thubba and the Buddhist triad seated in

endless

serenity. The walls were covered with

frescoes of great lamas,

and a series of alcoves, each with an image

representing an incarnation of Buddha, ran round the temple. In a chapel full of monstrous images and

piles of medallions made of the ashes of 'holy' men, the sub-abbot was

discoursing to the acolytes on the religious classics.

In the chapel of meditations, among lighted

incense sticks, monks seated before images were telling their beads

with the

object of working themselves into a state of ecstatic contemplation

(somewhat

resembling a certain hypnotic trance), for there are undoubtedly devout

lamas,

though the majority are idle and unholy. It

must be understood that all Tibetan literature is

'sacred,' though

some of the volumes of exquisite calligraphy on parchment, which for

our

benefit were divested of their silken and brocaded wrappings, contain

nothing

better than fairy tales and stories of doubtful morality, which are

recited by

the lamas

to the accompaniment of incessant cups of chang, as a religious duty

when they visit

their 'flocks' in the winter. The

Deskyid gonpo

contains 150 lamas,

all of whom have been educated at Lhassa. A

younger son in every household becomes a monk, and

occasionally enters

upon his vocation as an acolyte pupil as soon as weaned.

At the age of thirteen these acolytes are

sent to study at Lhassa for five or seven years, their departure being

made the

occasion of a great village feast, with several days of religious

observances. The close connection with

Lhassa, especially in the case of the yellow lamas, gives Nubra Buddhism

a singular interest. All the larger gonpos have their prototype in

Lhassa, all

ceremonial has originated in Lhassa, every instrument of worship has

been

consecrated in Lhassa, and every lama is educated in the

learning only to

be obtained at Lhassa. Buddhism is

indeed the most salient feature of Nubra. There

are gonpos

everywhere, the roads are lined by miles of chod-tens, manis,

and prayer-mills, and flags inscribed with sacred words in Sanskrit

flutter

from every roof. There are processions

of red and yellow lamas;

every act in trade, agriculture, and social life

needs the sanction of sacerdotalism; whatever exists of wealth is in

the gonpos,

which also have a monopoly of learning, and 11,000 monks closely linked

with

the laity, yet ruling all affairs of life and death and beyond death,

are all

connected by education, tradition, and authority with Lhassa. We

remained long on the blazing roof

of the highest tower of the gonpo, while good Mr. Redslob

disputed

with the abbot 'concerning the things pertaining to the kingdom of God.' The monks standing round laughed

sneeringly. They had shown a little

interest, Mr. R. said, on his earlier visits. The

abbot accepted a copy of the Gospel of St. John. 'St.

Matthew,' he observed, 'is very

laughable reading.' Blasts of wild music and the braying of colossal

horns

honoured our departure, and our difficult descent to the apricot groves

of

Deskyid. On our return to Hundar the

grain was ripe on Gergan's fields. The

first ripe ears were cut off, offered to the family divinity, and were

then

bound to the pillars of the house. In

the comparatively fertile Nubra valley the wheat and barley are cut,

not rooted

up. While they cut the grain the men

chant, 'May it increase, We will give to the poor, we will give to the lamas,'

with every stroke. They believe that it

can be made to multiply both under the sickle and in the threshing, and

perform

many religious rites for its increase while it is in sheaves. After eight days the corn is trodden out by

oxen on a threshing-floor renewed every year. After

winnowing with wooden forks, they make the grain

into a pyramid,

insert a sacred symbol, and pile upon it the threshing instruments and

sacks,

erecting an axe on the apex with its blade turned to the west, as that

is the

quarter from which demons are supposed to come. In the afternoon they

feast

round it, always giving a portion to the axe, saying, 'It is yours, it

belongs

not to me.' At dusk they pour it into

the sacks again, chanting, 'May it increase.' But

these are not removed to the granary until late at

night, at an hour

when the hands of the demons are too much benumbed by the nightly frost

to

diminish the store. At the beginning of

every one of these operations the presence of lamas is essential, to

announce the auspicious moment, and conduct religious ceremonies. They receive fees, and are regaled with

abundant chang and

the fat of the land. In Hundar,

as elsewhere, we were

made very welcome in all the houses. I have described the dwelling of

Gergan. The poorer peasants occupy

similar houses, but roughly built, and only two-storeyed, and the

floors are

merely clay. In them also the very

numerous lower rooms are used for cattle and fodder only, while the

upper part

consists of an inner or winter room, an outer or supper room, a

verandah room,

and a family temple. Among their rude

plenishings are large stone corn chests like sarcophagi, stone bowls

from

Baltistan, cauldrons, cooking pots, a tripod, wooden bowls, spoons, and

dishes,

earthen pots, and yaks'

and sheep's packsaddles. The garments of

the household are kept in long wooden boxes. Family life presents some curious features. In the disposal in marriage of a girl, her eldest brother has more 'say' than the parents. The eldest son brings home the bride to his father's house, but at a given age the old people are 'shelved,' i.e. they retire to a small house, which may be termed a 'jointure house,' and the eldest son assumes the patrimony and the rule of affairs. I have not met with a similar custom anywhere in the East. It is difficult to speak of Tibetan life, with all its affection and jollity, as 'family life,' for Buddhism, which enjoins monastic life, and usually celibacy along with it, on eleven thousand out of a total population of a hundred and twenty thousand, farther restrains the increase of population within the limits of sustenance by inculcating and rigidly upholding the system of polyandry, permitting marriage only to the eldest son, the heir of the land, while the bride accepts all his brothers as inferior or subordinate husbands, thus attaching the whole family to the soil and family roof-tree, the children being regarded legally as the property of the eldest son, who is addressed by them as 'Big Father,' his brothers receiving the title of 'Little Father.' The resolute determination, on economic as well as religious grounds, not to abandon this ancient custom, is the most formidable obstacle in the way of the reception of Christianity by the Tibetans. The women cling to it. They say, 'We have three or four men to help us instead of one,' and sneer at the dulness and monotony of European monogamous life! A woman said to me, 'If I had only one husband, and he died, I should be a widow; if I have two or three I am never a widow!' The word 'widow' is with them a term of reproach, and is applied abusively to animals and men. Children are brought up to be very obedient to fathers and mother, and to take great care of little ones and cattle. Parental affection is strong. Husbands and wives beat each other, but separation usually follows a violent outbreak of this kind. It is the custom for the men and women of a village to assemble when a bride enters the house of her husbands, each of them presenting her with three rupees. The Tibetan wife, far from spending these gifts on personal adornment, looks ahead, contemplating possible contingencies, and immediately hires a field, the produce of which is her own, and which accumulates year after year in a separate granary, so that she may not be portionless in case she leaves her husband!  Monastic Building at Basgu It was

impossible not to become

attached to the Nubra people, we lived so completely among them, and

met with

such unbounded goodwill. Feasts were given in our honour, every gonpo

was open to us, monkish blasts on colossal horns brayed out welcomes,

and while

nothing could exceed the helpfulness and alacrity of kindness shown by

all,

there was not a thought or suggestion of backsheesh.

The men of the villages always sat by our camp-fires

at night, friendly and jolly, but never obtrusive, telling stories,

discussing

local news and the oppressions exercised by the Kashmiri officials, the

designs

of Russia, the advance of the Central Asian Railway, and what they

consider as

the weakness of the Indian Government in not annexing the provinces of

the

northern frontier. Many of their ideas

and feelings are akin to ours, and a mutual understanding is not only

possible,

but inevitable1. Industry

in Nubra is the condition

of existence, and both sexes work hard enough to give a great zest to

the

holidays on religious festival days. Whether

in the house or journeying the men are never seen

without the

distaff. They weave also, and make the

clothes of the women and children! The

people are all cultivators, and make money also by undertaking the

transit of

the goods of the Yarkand traders over the lofty passes.

The men plough with the zho, or hybrid yak, and the women break the

clods and share in all other agricultural operations.

The soil, destitute of manure, which is dried and hoarded

for

fuel, rarely produces more than tenfold. The

'three acres and a cow' is with them four acres of

alluvial soil to

a family on an average, with 'runs' for yaks and sheep on the mountains. The farms, planted with apricot and other

fruit trees, a prolific loose-grained barley, wheat, peas, and lucerne,

are

oases in the surrounding deserts. The

people export apricot oil, dried apricots, sheep's wool, heavy undyed

woollens,

a coarse cloth made from yaks'

hair, and pashm, the

under fleece of the shawl goat. They

complained, and I think with good

reason, of the merciless exactions of the Kashmiri officials, but there

were no

evidences of severe poverty, and not one beggar was seen. It was not

an easy matter to get

back to Leh. The rise of the Shayok

made it impossible to reach and return by the Digar Pass, and the

alternative

route over the Kharzong glacier continued for some time impracticable—that

is, it was perfectly smooth ice. At

length the news came that a fall of snow had roughened its surface. A number of men worked for two days at

scaffolding a path, and with great difficulty, and the loss of one yak

from a falling rock, a fruitful source of fatalities in Tibet, we

reached

Khalsar, where with great regret we parted with Tse-ring-don-drub (Life's

purpose fulfilled), the gopa

of Sati, whose friendship had been a real pleasure, and to whose

courage and

promptitude, in Mr. Redslob's opinion, I owed my rescue from drowning. Two days of very severe marching and long

and steep ascents brought us to the wretched hamlet of Kharzong Lar-sa,

in a

snowstorm, at an altitude higher than the summit of Mont Blanc. The

servants

were all ill of 'pass-poison,' and crept into a cave along with a

number of big

Tibetan mastiffs, where they enjoyed the comfort of semi-suffocation

till the

next morning, Mr. R. and I, with some willing Tibetan helpers, pitching

our own

tents. The wind was strong and keen,

and with the mercury down at 15° Fahrenheit it was impossible to do

anything

but to go to bed in the early afternoon, and stay there till the next

day. Mr. Redslob took a severe chill,

which

produced an alarming attack of pleurisy, from the effects of which he

never

fully recovered. We started on a grim snowy morning, with six yaks carrying our baggage or ridden by ourselves, four led horses, and a number of Tibetans, several more having been sent on in advance to cut steps in the glacier and roughen them with gravel. Within certain limits the ground grows greener as one ascends, and we passed upwards among primulas, asters, a large blue myosotis, gentians, potentillas, and great sheets of edelweiss. At the glacier foot we skirted a deep green lake on snow with a glorious view of the Kharzong glacier and the pass, a nearly perpendicular wall of rock, bearing up a steep glacier and a snowfield of great width and depth, above which tower pinnacles of naked rock. It presented to all appearance an impassable barrier rising 2,500 feet above the lake, grand and awful in the dazzling whiteness of the new-fallen snow. Thanks to the ice steps our yaks took us over in four hours without a false step, and from the summit, a sharp ridge 17,500 feet in altitude, we looked our last on grimness, blackness, and snow, and southward for many a weary mile to the Indus valley lying in sunshine and summer. Fully two dozen caresses of horses newly dead lay in cavities of the glacier. Our animals were ill of 'pass-poison,' and nearly blind, and I was obliged to ride my yak into Leh, a severe march of thirteen hours, down miles of crumbling zigzags, and then among villages of irrigated terraces, till the grand view of the Gyalpo's palace, with its air-hung gonpo and clustering chod-tens, and of the desert city itself, burst suddenly upon us, and our benumbed and stiffened limbs thawed in the hot sunshine. I pitched my tent in a poplar grove for a fortnight, near the Moravian compounds and close to the travellers' bungalow, in which is a British Postal Agency, with a Tibetan postmaster who speaks English, a Christian, much trusted and respected, named Joldan, in whose intelligence, kindness, and friendship I found both interest and pleasure.  The Yak (Bos grunniens) ______________________ 1

Mr. Redslob said that when

on different occasions he was smitten by heavy

sorrows, he felt no

difference

between the Tibetan feeling and expression of sympathy and that of

Europeans. A

stronger testimony to

the effect produced by his twenty-five years of loving service could scarcely be given than

our welcome in Nubra. During

the dangerous illness which

followed,

anxious faces thronged his humble doorway as early as break of day. and the stream

of friendly inquiries never ceased till sunset, and when he

died the people of Ladak and Nubra wept and 'made

great mourning for him,' as for their truest

friend. |