| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2007 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER IV

MANNERS AND CUSTOMS Joldan, the Tibetan British postmaster in Leh, is a Christian of spotless reputation. Every one places unlimited confidence in his integrity and truthfulness, and his religious sincerity has been attested by many sacrifices. He is a Ladaki, and the family property was at Stok, a few miles from Leh. He was baptized in Lahul at twenty-three, his father having been a Christian. He learned Urdu, and was for ten years mission schoolmaster in Kylang, but returned to Leh a few years ago as postmaster. His 'ancestral dwelling' at Stok was destroyed by order of the wazir, and his property confiscated, after many unsuccessful efforts had been made to win him back to Buddhism. Afterwards he was detained by the wazir, and compelled to serve as a sepoy, till Mr. Heyde went to the council and obtained his release. His house in Leh has been more than once burned by incendiaries. But he pursues a quiet, even course, brings up his family after the best Christian traditions, refuses Buddhist suitors for his daughters, unobtrusively but capably helps the Moravian missionaries, supports his family by steady industry, although of noble birth, and asks nothing of any one. His 'good morning' and 'good night,' as he daily passed my tent with clockwork regularity, were full of cheery friendliness; he gave much useful information about Tibetan customs, and his ready helpfulness greatly facilitated the difficult arrangements for my farther journey.  A Chang-pa Woman The Leh, which I had left so dull and quiet, was full of strangers, traffic, and noise. The neat little Moravian church was filled by a motley crowd each Sunday, in which the few Christians were distinguishable by their clean faces and clothes and their devout air; and the Medical Mission Hospital and Dispensary, which in winter have an average attendance of only a hundred patients a month, were daily thronged with natives of India and Kashmir, Baltis, Yarkandis, Dards, and Tibetans. In my visits with Dr. Marx I observed, what was confirmed by four months' experience of the Tibetan villagers, that rheumatism, inflamed eyes and eyelids, and old age are the chief Tibetan maladies. Some of the Dards and Baltis were lepers, and the natives of India brought malarial fever, dysentery, and other serious diseases. The hospital, which is supported by the Indian Government, is most comfortable, a haven of rest for those who fall sick by the way. The hospital assistants are intelligent, thoroughly kind-hearted young Tibetans, who, by dint of careful drilling and an affectionate desire to please 'the teacher with the medicine box,' have become fairly trustworthy. They are not Christians. In the

neat dispensary at 9 a.m. a

gong summons the patients to the operating room for a short religious

service. Usually about fifty were present,

and a

number more, who had some curiosity about 'the way,' but did not care

to be

seen at Christian worship, hung about the doorways.

Dr. Marx read a few verses from the Gospels, explaining

them in a

homely manner, and concluded with the Lord's Prayer.

Then the out-patients were carefully and gently treated,

leprous

limbs were bathed and anointed, the wards were visited at noon and

again at

sunset, and in the afternoons operations were performed with the most

careful antiseptic

precautions, which are supposed to be used for the purpose of keeping

away evil

spirits from the wounds! The Tibetans,

in practice, are very simple in their applications of medical remedies. Rubbing with butter is their great

panacea. They have a dread of

small-pox, and instead of burning its victims they throw them into

their rapid

torrents. If an isolated case occur,

the sufferer is carried to a mountain-top, where he is left to recover

or die. If a small-pox epidemic is in the

province,

the people of the villages in which it has not yet appeared place

thorns on

their bridges and boundaries, to scare away the evil spirits which are

supposed

to carry the disease. In ordinary

illnesses, if butter taken internally as well as rubbed into the skin

does not

cure the patient, the lamas

are summoned to the rescue. They

make a mitsap,

a half life-size figure of the sick person, dress it in his or her

clothes and

ornaments, and place it in the courtyard, where they sit round it,

reading

passages from the sacred classics fitted for the occasion.

After a time, all rise except the superior lama,

who continues reading, and taking small drums in their left hands, they

recite

incantations, and dance wildly round the mitsap, believing, or at least

leading the

people to believe, that by this ceremony the malady, supposed to be the

work of

a demon, will be transferred to the image. Afterwards

the clothes and ornaments are presented to

them, and the

figure is carried in procession out of the yard and village and is

burned. If the patient becomes worse, the

friends

are apt to resort to the medical skill of the missionaries. If he dies

they are

blamed, and if he recovers the lamas take the credit. At some

little distance outside Leh

are the cremation grounds—desert

places, destitute of any other

vegetation than the Caprifolia

horrida. Each family has its

furnace kept in good

repair. The place is doleful, and a

funeral scene on the only sunless day I experienced in Ladak was

indescribably

dismal. After death no one touches the

corpse but the lamas,

who assemble in numbers in the case of a rich

man. The senior lama offers the first

prayers, and lifts the lock which all Tibetans wear at the back of the

head, in

order to liberate the soul if it is still clinging to the body. At the same time he touches the region of

the heart with a dagger. The people

believe that a drop of blood on the head marks the spot where the soul

has made

its exit. Any good clothing in which

the person has died is then removed. The

blacksmith beats a drum, and the corpse, covered with

a white sheet

next the dress and a coloured one above, is carried out of the house to

be

worshipped by the relatives, who walk seven times round it. The women then retire to the house, and the

chief lama

recites liturgical passages from the formularies. Afterwards, the

relatives

retire, and the corpse is carried to the burning-ground by men who have

the

same tutelar deity as the deceased. The

leading lama

walks first, then come men with flags, followed by the blacksmith with

the

drum, and next the corpse, with another man beating a drum behind it. Meanwhile, the lamas are praying for the

repose and quieting of the soul, which is hovering about, desiring to

return. The attendant friends, each of

whom has carried a piece of wood to the burning-ground, arrange the

fuel with

butter on the furnace, the corpse wrapped in the white sheet is put in,

and

fire is applied. The process of

destruction in a rich man's case takes about an hour.

During the burning the lamas read in high, hoarse

monotones, and

the blacksmiths beat their drums. The lamas

depart first, and the blacksmiths, after worshipping the ashes, shout,

'Have

nothing to do with us now,' and run rapidly away. At

dawn the following day, a man whose business it is searches

among the ashes for the footprints of animals, and according to the

footprints

found, so it is believed will be the re-birth of the soul. Some of

the ashes are taken to the gonpos,

where the lamas

mix them with clay, put them into oval or circular moulds, and stamp

them with

the image of Buddha. These are

preserved in chod-tens,

and in the house of the nearest relative of the

deceased; but in the case of 'holy' men, they are retained in the gonpos,

where they can be purchased by the devout. After

a cremation much chang is

consumed by the

friends, who make

presents to the bereaved family. The

value of each is carefully entered in a book, so that a precise return

may be

made when a similar occasion occurs. Until

the fourth day after death it is believed to be

impossible to

quiet the soul. On that day a piece of

paper is inscribed with prayers and requests to the soul to be quiet,

and this

is burned by the lamas

with suitable ceremonies; and rites of a more or less

elaborate kind are afterwards performed for the repose of the soul,

accompanied

with prayers that it may get 'a good path' for its re-birth, and food

is placed

in conspicuous places about the house, that it may understand that its

relatives are willing to support it. The

mourners for some time wear wretched clothes, and

neither dress

their hair nor wash their faces. Every year the lamas sell by auction the

clothing and ornaments, which are their perquisites at funerals1. The Moravian missionaries have opened a school in Leh, and the wazir, finding that the Leh people are the worst educated in the country, ordered that one child at least in each family should be sent to it. This awakened grave suspicions, and the people hunted for reasons for it. 'The boys are to be trained as porters, and made to carry burdens over the mountains,' said some. 'Nay,' said others, 'they are to be sent to England and made Christians of.' [All foreigners, no matter what their nationality is, are supposed to be English.] Others again said, 'They are to be kidnapped,' and so the decree was ignored, till Mr. Redslob and Dr. Marx went among the parents and explained matters, and a large attendance was the result; for the Tibetans of the trade route have come to look upon the acquisition of 'foreign learning' as the stepping-stone to Government appointments at ten rupees per month. Attendance on religious instruction was left optional, but after a time sixty pupils were regularly present at the daily reading and explanation of the Gospels. Tibetan fathers teach their sons to write, to read the sacred classics, and to calculate with a frame of balls on wires. If farther instruction is thought desirable, the boys are sent to the lamas, and even to the schools at Lhassa. The Tibetans willingly receive and read translations of our Christian books, and some go so far as to think that their teachings are 'stronger' than those of their own, indicating their opinions by tearing pages out of the Gospels and rolling them up into pills, which are swallowed in the belief that they are an effective charm. Sorcery is largely used in the treatment of the sick. The books which instruct in the black art are known as 'black books.' Those which treat of medicine are termed 'blue books.' Medical knowledge is handed down from father to son. The doctors know the virtues of in any of the plants of the country, quantities of which they mix up together while reciting magical formulas.  Chang-pa Chief I was

heartily sorry to leave Leh,

with its dazzling skies and abounding colour and movement, its stirring

topics

of talk, and the culture and exceeding kindness of the Moravian

missionaries.

Helpfulness was the rule. Gergan came

over the Kharzong glacier on purpose to bring me a prayer-wheel;

Lob-sang and

Tse-ring-don-drub, the hospital assistants, made me a tent carpet of yak's

hair cloth, singing as they sewed; and Joldan helped to secure

transport for

the twenty-two days' journey to Kylang. Leh

has few of what Europeans regard as travelling

necessaries. The brick tea which I

purchased from a

Lhassa trader was disgusting. I

afterwards understood that blood is used in making up the blocks. The flour was gritty, and a leg of mutton

turned out to be a limb of a goat of much experience. There were no

straps, or

leather to make them of, in the bazaar, and no buckles; and when the

latter

were provided by Mr. Redslob, the old man who came to sew them upon a

warm rug

which I had made for Gyalpo out of pieces of carpet and hair-cloth put

them on

wrongly three times, saying after each failure, 'I'm very foolish. Foreign ways are so wonderful!'

At times the Tibetans say, 'We're as stupid

as oxen,' and I was inclined to think so, as I stood for two hours

instructing

the blacksmith about making shoes for Gyalpo, which kept turning out

either too

small for a mule or too big for a dray-horse. I obtained

two Lahul muleteers with

four horses, quiet, obliging men, and two superb yaks, which were loaded with

twelve days' hay and barley for my horse. Provisions

for the whole party for the same time had to be

carried, for

the route is over an uninhabited and arid desert. Not

the least important part of my outfit was a letter from Mr.

Redslob to the headman or chief of the Chang-pas or Champas, the

nomadic tribes

of Rupchu, to whose encampment I purposed to make a détour. These

nomads

had on two occasions borrowed money from the Moravian missionaries for

the

payment of the Kashmiri tribute, and had repaid it before it was due,

showing

much gratitude for the loans. Dr. Marx

accompanied me for the

three first days. The few native

Christians in Leh assembled in the gay garden plot of the lowly

mission-house

to shake hands and wish me a good journey, and not a few who were not

Christians, some of them walking for the first hour beside our horses. The road from Leh descends to a rude wooden

bridge over the Indus, a mighty stream even there, over blazing slopes

of

gravel dignified by colossal manis and chod-tens in long lines,

built by the former kings of Ladak. On

the other side of the river gravel slopes ascend towards red mountains

20,000

feet in height. Then comes a rocky spur

crowned by the imposing castle of the Gyalpo, the son of the dethroned

king of

Ladak, surmounted by a forest of poles from which flutter yaks' tails and long

streamers inscribed with prayers. Others

bear aloft the trident, the emblem of Siva. Carefully

hewn zigzags, entered through a

much-decorated and colossal chod-ten, lead to the castle. The village of Stok, the prettiest and most

prosperous in Ladak, fills up the mouth of a gorge with its large

farm-houses

among poplar, apricot, and willow plantations, and irrigated terraces

of

barley; and is imposing as well as pretty, for the two roads by which

it is

approached are avenues of lofty chod-tens and broad manis, all in excellent

repair. Knolls, and deeply coloured spurs of naked rock, most

picturesquely

crowded with chod-tens,

rise above the greenery, breaking the purple

gloom of the gorge which cuts deeply into the mountains, and supplies

from its

rushing glacier torrent the living waters which create this delightful

oasis. The gopa came forth

to meet us,

bearing apricots and cheeses as the Gyalpo's greeting, and conducted us

to the

camping-ground, a sloping lawn in a willow-wood, with many a natural

bower of

the graceful Clematis orientalis. The tents were pitched, afternoon tea was on

a table outside, a clear, swift stream made fitting music, the

dissonance of

the ceaseless beating of gongs and drums in the castle temple was

softened by

distance, the air was cool, a lemon light bathed the foreground, and to

the

north, across the Indus, the great mountains of the Leh range, with

every cleft

defined in purple or blue, lifted their vermilion peaks into a rosy sky. It was the poetry and luxury of travel. At Leh I

was obliged to dismiss the seis

for prolonged misconduct and cruelty

to Gyalpo, and Mando undertook to take care of him.

The animal had always been held by two men while the seis

groomed

him with difficulty, but at Stok, when Mando rubbed him down, he

quietly went

on feeding and laid his lovely head on the lad's shoulder with a soft

cooing

sound. From that moment Mando could do

anything with him, and a singular attachment grew up between man and

horse. Towards

sunset we were received by

the Gyalpo. The castle loses nothing of

its picturesqueness on a nearer view, and everything about it is trim

and in

good order, it is a substantial mass of stone building on a lofty rock,

the

irregularities of which have been taken most artistic advantage of in

order to

give picturesque irregularity to the edifice, which, while six storeys

high in

some places, is only three in others. As

in the palace of Leh, the walls slope inwards from the

base, where

they are ten feet thick, and projecting balconies of brown wood and

grey stone

relieve their monotony. We were

received at the entrance by a number of red lamas, who took us up five

flights of rude

stairs to the reception room, where we were introduced to the Gyalpo,

who was

in the midst of a crowd of monks, and, except that his hair was not

shorn, and

that he wore a silver brocade cap and large gold earrings and

bracelets, was

dressed in red like them. Throneless

and childless, the Gyalpo has given himself up to religion. He has covered the castle roof with Buddhist

emblems (not represented in the sketch). From

a pole, forty feet long, on the terrace floats a

broad streamer of

equal length, completely covered with Aum mani padne hun, and he has

surrounded

himself with lamas,

who conduct nearly ceaseless services in the

sanctuary. The attainment of merit, as

his creed leads him to understand it, is his one aim in life. He loves the seclusion of Stok, and rarely

visits the palace in Leh, except at the time of the winter games, when

the

whole population assembles in cheery, orderly crowds, to witness races,

polo

and archery matches, and a species of hockey. He

interests himself in the prosperity of Stok, plants

poplars, willows,

and fruit trees, and keeps the castle manis

and chod-tens

in admirable repair. Stok

Castle is as massive as any of

our mediaeval buildings, but is far lighter and roomier.

It is most interesting to see a style of

architecture and civilisation which bears not a solitary trace of

European

influence, not even in Manchester cottons or Russian gimcracks. The Gyalpo's room was only roofed for six

feet within the walls, where it was supported by red pillars. Above, the deep blue Tibetan sky was

flushing with the red of sunset, and from a noble window with a covered

stone

balcony there was an enchanting prospect of red ranges passing into

translucent

amethyst. The partial ceiling is

painted in arabesques, and at one end of the room is an alcove, much

enriched

with bold wood carving. The Gyalpo was seated on a carpet on the floor, a smooth-faced, rather stupid-looking man of twenty-eight. He placed us on a carpet beside him, and coffee, honey, and apricots were brought in, but the conversation flagged. He neither suggested anything nor took up Dr. Marx's suggestions. Fortunately, we had brought our sketch-books, and the views of several places were recognised, and were found interesting. The lamas and servants, who had remained respectfully standing, sat down on the floor, and even the Gyalpo became animated. So our visit ended successfully.  The Castle of Stok There is a

doorway from the

reception room into the sanctuary, and after a time fully thirty lamas

passed in and began service, but the Gyalpo only stood on his carpet. There is only a half light in this temple,

which is further obscured by scores of smoked and dusty bannerets of

gold and

silver brocade hanging from the roof. In

addition to the usual Buddhist emblems there are

musical instruments,

exquisitely inlaid, or enriched with niello

work of gold and silver of great antiquity, and bows of singular

strength,

requiring two men to bend them, which are made of small pieces of horn

cleverly

joined. Lamas

gabbled liturgies at railroad speed, beating drums and clashing cymbals

as an

accompaniment, while others blew occasional blasts on the colossal

silver horns

or trumpets, which probably resemble those with which Jericho was

encompassed. The music, the discordant

and high-pitched monotones, and the revolting odours of stale smoke of

juniper

chips, of rancid butter, and of unwashed woollen clothes which drifted

through

the doorway, were over-powering. Attempted

fights among the horses woke me often during the

night, and

the sound of worship was always borne over the still air. Dr. Marx

left on the third day,

after we had visited the monastery of Hemis, the richest in Ladak,

holding

large landed property and possessing much metallic wealth, including a chod-ten

of silver and gold, thirty feet high, in one of its many halls,

approached by

gold- plated silver steps and incrusted with precious stones; there is

also

much fine work in brass and bronze. Hemis

abounds in decorated buildings most picturesquely

placed, it has

three hundred lamas,

and is regarded as 'the sight' of Ladak. At Upschi,

after a day's march over

blazing gravel, I left the rushing olive-green Indus, which I had

followed from

the bridge of Khalsi, where a turbulent torrent, the Upshi water, joins

it,

descending through a gorge so narrow that the track, which at all times

is

blasted on the face of the precipice, is occasionally scaffolded. A very extensive rock-slip had carried away

the path and rendered several fords necessary, and before I reached it

rumour

was busy with the peril. It was true

that the day before several mules had been carried away and drowned,

that many

loads had been sacrificed, and that one native traveller had lost his

life. So I started my caravan at

daybreak, to get the water at its lowest, and ascended the gorge, which

is an

absolutely verdureless rift in mountains of most brilliant and

fantastic

stratification. At the first ford Mando

was carried down the river for a short distance. The second was deep

and

strong, and a caravan of valuable goods had been there for two days,

afraid to

risk the crossing. My Lahulis, who

always showed a great lack of stamina, sat down, sobbing and beating

their

breasts. Their sole wealth, they said,

was in their baggage animals, and the river was 'wicked,' and 'a demon'

lived

in it who paralysed the horses' legs. Much

experience of Orientals and of travel has taught me

to surmount difficulties

in my own way, so, beckoning to two men from the opposite side, who

came over

shakily with linked arms, I took the two strong ropes which I always

carry on

my saddle, and roped these men together and to Gyalpo's halter with

one, and

lashed Mando and the guide together with the other, giving them the

stout

thongs behind the saddle to hold on to, and in this compact mass we

stood the

strong rush of the river safely, the paralysing chill of its icy waters

being a

far more obvious peril. All the baggage animals were brought over in

the same

way, and the Lahulis praised their gods. At Gya, a

wild hamlet, the last in

Ladak proper, I met a working naturalist whom I had seen twice before,

and

'forgathered' with him much of the way. Eleven

days of solitary desert succeeded. The

reader has probably understood that no part of the

Indus,

Shayok, and Nubra valleys, which make up most of the province of Ladak,

is less

than 9,500 feet in altitude, and that the remainder is composed of

precipitous

mountains with glaciers and snowfields, ranging from 18,000 to 25,000

feet, and

that the villages are built mainly on alluvial soil where possibilities

of

irrigation exist. But Rupchu has

peculiarities of its own. Between

Gya and Darcha, the first

hamlet in Lahul, are three huge passes, the Toglang, 18,150 feet in

altitude,

the Lachalang, 17,500, and the Baralacha, 16,000,—all easy, except for the

difficulties arising from the highly rarefied air.

The mountains of the region, which are from 20,000 to

23,000 feet

in altitude, are seldom precipitous or picturesque, except the huge red

needles

which guard the Lachalang Pass, but are rather 'monstrous

protuberances,' with

arid surfaces of disintegrated rock. Among

these are remarkable plateaux, which are taken

advantage of by

caravans, and which have elevations of from 14,000 to 15,000 feet. There are few permanent rivers or streams,

the lakes are salt, beside the springs, and on the plateaux there is

scanty

vegetation, chiefly aromatic herbs; but on the whole Rupchu is a desert

of arid

gravel. Its only inhabitants are 500

nomads, and on the ten marches of the trade route, the bridle paths, on

which

in some places labour has been spent, the tracks, not always very

legible, made

by the passage of caravans, and rude dykes, behind which travellers may

shelter

themselves from the wind, are the only traces of man.

Herds of the kyang,

the wild horse of some naturalists, and the wild ass of others,

graceful and

beautiful creatures, graze within gunshot of the track without alarm. I had

thought Ladak windy, but

Rupchu is the home of the winds, and the marches must be arranged for

the

quietest time of the day. Happily the

gales blow with clockwork regularity, the day wind from the south and

south-west rising punctually at 9 a.m. and attaining its maximum at

2.30, while

the night wind from the north and north-east rises about 9 p.m. and

ceases

about 5 a.m. Perfect silence is

rare. The highly rarefied air, rushing

at great speed, when at its worst deprives the traveller of breath,

skins his

face and hands, and paralyses the baggage animals.

In fact, neither man nor beast can face it.

The horses 'turn tail' and crowd together,

and the men build up the baggage into a wall and crouch in the lee of

it. The heat of the solar rays is at the

same

time fearful. At Lachalang, at a height

of over 15,000 feet, I noted a solar temperature of 152°, only 35°

below the boiling point of water in the same region, which is about 187°.

To make up for this, the mercury falls below

the freezing point every night of the year, even in August the

difference of

temperature in twelve hours often exceeding 120°! The

Rupchu nomads, however, delight in this climate of extremes,

and regard Leh as a place only to be visited in winter, and Kulu and

Kashmir as

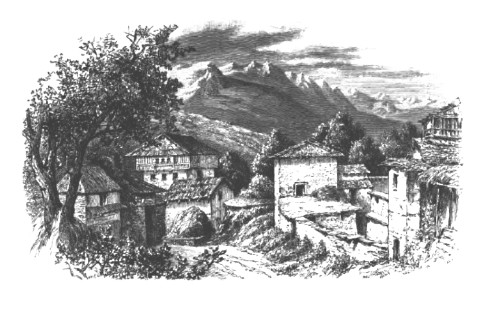

if they were the malarial swamps of the Congo! We crossed the Toglang Pass, at a height of 18,150 feet, with less suffering from ladug than on either the Digar or Kharzong Passes. Indeed Gyalpo carried me over it stopping to take breath every few yards. It was then a long dreary march to the camping-ground of Tsala, where the Chang-pas spend the four summer months; the guides and baggage animals lost the way and did not appear until the next day, and in consequence the servants slept unsheltered in the snow. News travels as if by magic in desert places. Towards evening, while riding by a stream up a long and tedious valley, I saw a number of moving specks on the crest of a hill, and down came a surge of horsemen riding furiously. Just as they threatened to sweep Gyalpo away, they threw their horses on their haunches, in one moment were on the ground, which they touched with their foreheads, presented me with a plate of apricots, and the next vaulted into their saddles, and dashing up the valley were soon out of sight. In another half- hour there was a second wild rush of horsemen, the headman dismounted, threw himself on his face, kissed my hand, vaulted into the saddle, and then led a swirl of his tribesmen at a gallop in ever-narrowing circles round me till they subsided into the decorum of an escort. An elevated plateau with some vegetation on it, a row of forty tents, 'black' but not 'comely,' a bright rapid river, wild hills, long lines of white sheep converging towards the camp, yaks rampaging down the hillsides, men running to meet us, and women and children in the distance were singularly idealised in the golden glow of a cool, moist evening.  First Village in Kulu Two men

took my bridle, and two more

proceeded to put their hands on my stirrups; but Gyalpo kicked them to

the

right and left amidst shrieks of laughter, after which, with frantic

gesticulations and yells of 'Kabardar!',

I was led through the river in triumph and hauled off my horse. The tribesmen were much excited.

Some dashed about, performing feats of

horsemanship; others brought apricots and dough-balls made with apricot

oil, or

rushed to the tents, returning with rugs; some cleared the

camping-ground of

stones and raised a stone platform, and a flock of goats, exquisitely

white

from the daily swims across the river, were brought to be milked. Gradually and shrinkingly the women and

children drew near; but Mr.—'s Bengali servant threatened them with a

whip,

when there was a general stampede, the women running like hares. I had trained my servants to treat the

natives courteously, and addressed some rather strong language to the

offender,

and afterwards succeeded in enticing all the fugitives back by showing

my

sketches, which gave boundless pleasure and led to very numerous

requests for

portraits! The gopa, though he had the

oblique Mongolian eyes, was a handsome young man, with a good nose and

mouth. He was dressed like the others

in a girdled chaga of

coarse

serge, but wore a red cap turned up over the ears with fine fur, a

silver

inkhorn, and a Yarkand knife in a chased silver sheath in his girdle,

and

canary-coloured leather shoes with turned-up points.

The people prepared one of their own tents for me, and

laying

down a number of rugs of their own dyeing and weaving, assured me of an

unbounded welcome as a friend of their 'benefactor,' Mr. Redslob, and

then

proposed that I should visit their tents accompanied by all the elders

of the

tribe. 1 For these and other

curious details concerning Tibetan customs I am indebted to the

kindness and

careful investigations of the late Rev. W. Redslob, of Leh, and the

rev. A.

Heyde, of Kylang. |