| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2009 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

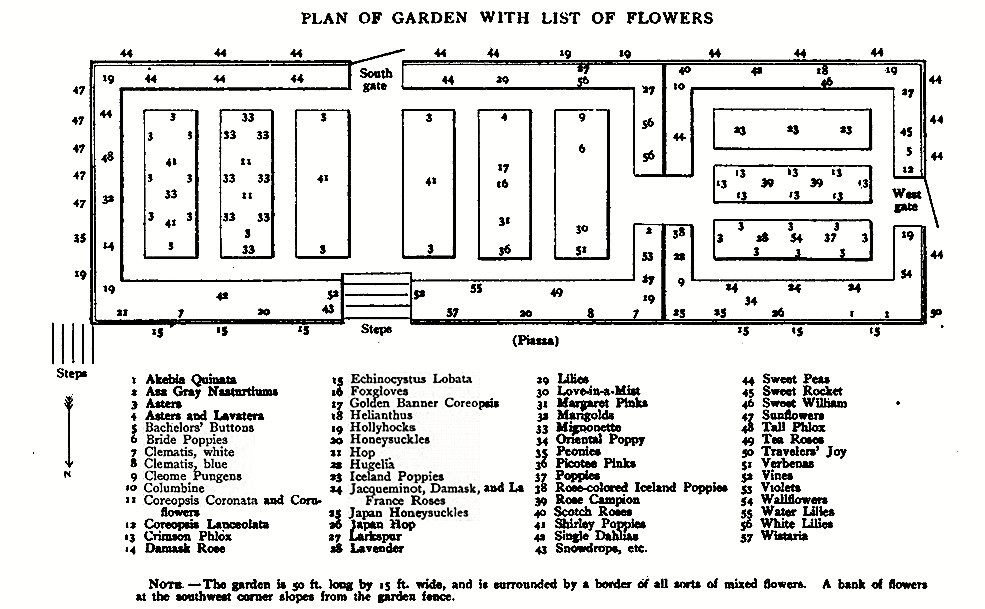

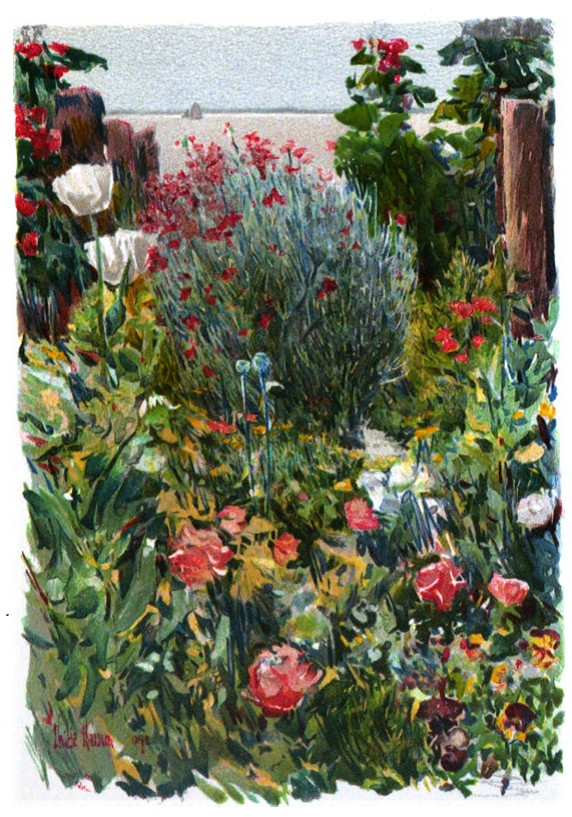

MUCH thought should be given to the garden's arrangement with regard to economy of room, where one has but a small space to devote to it. And where one is unfamiliar with the habits of growth of the various plants that are to people it, a difficulty arises in making them effective and so disposing them that they shall not interfere with each other. For instance, in most cases tall plants should be put back against walls and fences and so forth, with the lower-growing varieties in the foreground. If one were to plant Verbenas and Venidium among Sunflowers and Hollyhocks, or even among Carnation Poppies and Cornflowers, Verbenas and Venidium would not be visible, for their habit is to creep close to the ground, and the tall growths would completely hide and most likely exterminate them, by shutting from them the sun and air without which they cannot live. These low, creeping plants are, however, very useful when one is planning for a succession of flowers. I plant Pansies, Verbenas, Drummond's Phlox, and so forth, among my Pinks and Wallflowers and others of like compact habit, so that, when the higher slender plants have done blossoming, the others, which seldom cease flowering till frost, may still clothe the ground with color and beauty. Of course it goes without saying that climbing Vines should not be set where there is nothing upon which they may climb. Indeed that would be simple cruelty — nothing more nor less. Everything that needs it should be given a support without fail — all the myriad lovely Vines that one may have with so little trouble, and which seem to have been made to wreathe the dwellings of men with freshness and beauty and grace. The long list of varieties of flowering Clematis, so many shapes and colors, the numerous Honeysuckles, the Wistaria, Passion-flowers, Morning-glories, Hops, the Dutchman's Pipe, the Cobśas, Woodbine, and many others, not counting Sweet Peas and Nasturtiums, — these last among the most beautiful and decorative of all, — every one is twice as valuable if given the support it demands. In the case of Nasturtiums, however, which seem with endless good-nature ready to adapt themselves to any conditions of existence, except, perhaps, being expected to live in a swamp, it is not so important that they should have something upon which to climb. A very good way is to put them near a rock one wishes to have covered, or to let them run down a bank upon which nothing else cares to grow. They will clothe such places with wild and beautiful luxuriance of green leaves and glowing flowers. It seems strange to write a book about a little garden only fifty feet long by fifteen wide! But then, as a friend pleasantly remarked to me, "it extends upward," and what it lacks in area is more than compensated by the large joy that grows out of it and its uplifting and refreshment of " the Spirit of Man." I have made a plan of this minute domain to show how it may be possible to accomplish much within such narrow compass, and also to give an idea of an advantageous method of grouping in a space so confined. I have not room to experiment with rockworks and ribbon-borders and the like, nor should I do it even if I had all the room in the world. For mine is just a little old-fashioned garden where the flowers come together to praise the Lord and teach all who look upon them to do likewise.  All through the months of April and May, when the weather is not simply impossible, I am at work in it, and also through most of June. It is wonderful how much work one can find to do in so tiny a plot of ground. But in the latter weeks of June there comes a time when I can begin to take breath and rest a little from these difficult yet pleasant labors; an interval when I may take time to consider, a morning when I may seek the hammock in the shady piazza, and, looking across my happy flower beds, let the sweet day sink deep into my heart. From the flower beds I look over the island slopes to the sea, and realize it all, — the rapture of growth, the delicious shades of green that clothe the ground, Wild Rose, Bayberry, Spirea, Shadbush, Elder, and many more. I-low beautiful they are, these grassy, rocky slopes shelving gradually to the sea, with here and there a mass of tall, blossoming grass softly swaying in the warm wind against the peaceful, pale blue water! Among the grass a few ghostly dandelion tops yet linger, with now and then a belated golden flower. How lovely is the delicacy of the white bleached rocks, the little spaces of shallow soil exquisite with vivid crimson Sorrel, or pearly with the brave Eyebright, all against the soft color of the sea. What harmony of movement in all these radiant growths just stirred by the gentle air! Here and there a stout little bough of Chokecherry, with clustered white blossoms tipped with pink, springing from a cleft in the rock, lights up in sunshine, its pink more glowing for the turquoise background of the ocean. How hot the sun blazes The Blue-eyed Grass is quite faint and drooping in the rich turf, but the yellow Crowfoot shines strong and steady; no sunshine is too bright for it. In the garden the tall Jacqueminot Rosebushes gather power from the great warmth and light, and hold out their thick buds to absorb it and fold its splendor in their inmost hearts. One or two of the heaviest buds begin to loosen their crimson velvet petals and shed their delicious perfume on the air. The Oriental Poppy glories in the heat. Among its buds, thrust upward like solid green apples, one has burst into burning flame, each of its broad fiery petals as large as the whole inside of my hand. In the Iceland Poppy bed the ardent light has wooed a graceful company of drooping buds to blow, and their cups of delicate fire, orange and yellow, sway lightly on stems as slender as grass. In sheltered corners the Forget-me-not spreads its cool, heaven-blue clusters; by the fence "the Larkspurs listen" while they wait; the large purple Pansies shrink and turn from the too brilliant gaze of the sun. Rose Campions, Tea Roses, Mignonette, Marigolds, Coreopsis, the rows of Sweet Peas, the broad-leaved Hollyhocks and the rest, rejoice and grow visibly with every moment of the glorious day. Clematis and Honeysuckle almost seem to hurry, Nasturtiums reach their shield-like leaves and wind the stems thereof round any and every stick and string they can touch by which to lift themselves, here and there showing their first glowing flowers, and climbing eagerly. The long large buds of the white Clematis, the earliest of all, are swelling visibly before my eyes, and the buds of the early June Honeysuckle are reddening at the end of every spray. In one corner a tall purple Columbine hangs its myriad clustered bells; each flower has six shell-like whorls set in a circle, colored like rich amethysts and lined with lustrous silver, white as frost. Cornflowers like living sparks of exquisite color, rose and azure, white and purple, twinkle all over the place, and the heavenly procession begins in good earnest. The Grapevine smooths out its young leaves, — they are woolly and crimson; the wind blows and shows me their grayish-white under surfaces. I think of Browning's tender song, the verse, — "The

leaf buds on the vine are woolly,

I noticed that to-day, One day more bursts them open fully, You know the red turns gray." The Echinocystus plants that have sprung in thick ranks along the edge of the beds. against the piazza are fairly storming up the trellis, having sown themselves in the autumn; they have just really begun to take firm hold, and are climbing hand over hand, as sailors do, with their strong green tendrils stretching out like arms and hands to right and left, laying hold of every available. thing by which to cling and spring upward to the very eaves. There in August they form a closely woven curtain of lush, light green, overhung with large, loose clusters of starry white flowers having a pure, delicious fragrance like honey and the wax of the comb. Now come the most perfect days of the year, blue days, hot on the continent, but heavenly here, where the cool breeze breathes round the islands. from the great expanse of whispering water. Delightful it is to lie here and rest and realize all this beauty and rejoice in all its joy! The distant coast-line is dim in soft mirage. "Half

lost in the liquid azure bloom of a crescent of sea,

The silent, sapphire-spangled, marriage-ring of the land." It lies so lovely, far away! At its edge the water is glassy calm, the houses and large, glimmering piles of buildings along its whole length show white in the hot haze; in the offing the far-off sails are half lost in this shimmering veil; farther out there is a soft wind blowing; little fishing-boats with their sails furled lie at anchor between us and the land, faintly outlined against the delicate tone of the water. All is so still! I hear a bee go blundering into the Bachelor's Buttons that hold up their flowers to the sun like small, compact yellow Roses. Suddenly comes a gush of the song-sparrow's music, but father martin sits at his door very quiet; it is too hot on the red roof of his little house, so he sits at its portal and meditates while his small wife broods within, only now and then from his pretty throat pours a low ripple of sound, melodiously content. I am conscious of the sandpiper calling and the full tide murmuring, and I, too, am content.  The Bride Outside the garden fence it is as if the flowers had broken their bounds and were rushing down the sloping bank in a torrent of yellow, where the early Artemisias and Eschscholtzias are hastening into bloom, overflowing in a flood of gold that, lightly stirred by every breeze, sends a satin shimmer to the sun. Eschscholtzia — it is an ugly name for a most lovely flower. California Poppy is much better. Down into the sweet plot I go and gather a few of these, bringing them to my little table and sitting down before them the better to admire and adore their beauty. In the slender green glass in which I put them they stand clothed in their delicate splendor. One blossom I take in a loving hand the more closely to examine it, and it breathes a glory of color into sense and spirit which is enough to kindle the dullest imagination. The stems and fine thread-like leaves are smooth and cool gray-green, as if to temper the fire of the blossoms, which are smooth also, unlike almost all other Poppies, that are crumpled past endurance in their close green buds, and make one feel as if they could not wait to break out of the calyx and loosen their petals to the sun, to be soothed into even tranquillity of beauty by the touches of the air. Every cool gray-green leaf is tipped with a tiny line of red, every flower-bud wears a little pale-green pointed cap like an elf, and in the early morning, when the bud is ready to blow, it pushes off the pretty cap and unfolds all its loveliness to the sun. Nothing could be more picturesque than this fairy cap, and nothing more charming than to watch the blossom push it off and spread its yellow petals, slowly rounding to the perfect cup. As I hold the flower in my hand and think of trying to describe it, I realize how poor a creature I am, how impotent are words in the presence of such perfection. It is held upright upon a straight and polished stem, its petals curving upward and outward into the cup of light, pure gold with a lustrous satin sheen; a rich orange is painted on the gold, drawn in infinitely fine lines to a point in the centre of the edge of each petal, so that the effect is that of a diamond of flame in a cup of gold. It is not enough that the powdery anthers are orange bordered with gold; they are whirled about the very heart of the flower like a revolving Catherine-wheel of fire. In the centre of the anthers is a shining point of warm sea-green, a last, consummate touch which makes the beauty of the blossom supreme. Another has the orange suffused through the gold evenly, almost to the outer edges of the petals, which are left in bright, light yellow with a dazzling effect. Turning the flower and looking at it from the outside, it has no calyx, but the petals spring from a simple pale-green disk, which must needs be edged with sea-shell pink for the glory of God! The fresh splendor of this flower no tongue nor pen nor brush of mortal man can fitly represent. Who indeed shall adequately describe any one, the simplest even, of these radiant beings? Day after day, as I watch them appear, one variety after another, in such endless changes of delicate beauty, I can but marvel ever more and more at the exhaustless power of the great Inventor. Must He not enjoy the work of His hands, the manifold perfection of these His matchless creations? Who can behold the unfolding of each new spring and all its blossoms without feeling the renewal of "God's ancient rapture," of which Browning speaks in "Paracelsus"? In that immortal rapture, I, another of his creatures, less obedient in fulfilling His laws of beauty than are these lovely beings, do humbly share, reflecting it with all the powers of my spirit and rejoicing in His work with an exceeding joy. As the days go on toward July, the earth becomes dry and all the flowers begin to thirst for moisture. Then from the hillside, some warm, still evening, the sweet rain-song of the robin echoes clear, and next day we wake to a dim morning; soft flecks of cloud bar the sun's way, fleecy vapors steal across the sky, the southwest wind blows lightly, rippling the water into little waves that murmur melodiously as they kiss the shore. In this warm gray, brooding light I am reminded of Tennyson's subtle description of such a daybreak: — "When

the first low matin chirp

hath grown

Full quire, and morning driven her plough of pearl Far furrowing into light the mounded rack, Beyond the fair green field and eastern sea."

Through the early hours of the day the mottled, pearly clouds keep their shape, with delicious open spaces of tempered blue between; by and by the sky's tender fleece is half shadowed, toward noon it melts into loose mists. Color everywhere tells against these pellucid grays, — the gold of Lemon Lilies, the flame of Iceland Poppies, all the sweet tints of every blossom. Presently the happy rain begins to fall, so soft, so warm, so peaceful, the very sound of it is a pleasure; every leaf in the patient garden, which has waited for the shower so long, spreads itself wide to catch each crystal drop and treasure its deep refreshment. All day it rains; at night the melody lulls us to sleep as it patters on the roof. In the night the wind changes, and next day brings a northeast storm again with a wild wind, but from this the little flower plot is well protected, and I rejoice in the thorough watering deep down among their roots which is doing all the plants unmeasured good. Two, perhaps three days, it lasts, the gale blowing till there is such contention of winds and waves about the little isle as to make a ceaseless roaring of wild breakers round its shores. When at last the tempest wears itself out, what delight there is in the great tranquillity that follows it; what music in the soft, far murmurs of ceasing strife in air and ocean, spent wrath that seems to breathe yet in an undertone, half sullen, half relenting, while the broad yellow light that lies over sea and rocks in stillness, like a quiet smile, promises a heavenly day on the morrow. Then, with what fresh wealth of color and perfume the garden will meet the resplendent sunrise! Every moment it grows more and more beautiful. I think for wondrous variety, for certain picturesque qualities, for color and form and a subtle mystery of character, Poppies seem, on the whole, the most satisfactory flowers among the annuals. There is absolutely no limit to their variety of color. They are the tenderest lilac, the deepest crimson, richest scarlet, white with softest suffusion of rose; all shades of rose, clear light pink with sea-green centre, the anthers in a golden halo about it; black and fire-color; red that is deepened to black, with gray reflections; cherry-color, with a cross of creamy white at the bottom of the cup, and round its central altar of ineffable golden green again the halo of yellow anthers; purple, with rich splashes of a deeper shade of the same color, with grayish white rays about the centre; all shades of lavender and lilac; exquisite smoke-color, in some cases delicately touched and freaked with red; some pure light gray, some of these gray ones edged with crimson or scarlet; there are all tints of mauve. To tell all the combinations of their wonderful hues, or even half, would be quite impossible, from the simple transparent scarlet bell of the wild Poppy to the marvelous pure white, the wonder of which no tongue can tell. Oh, these white Poppies, some with petals more delicate than the finest tissue paper, with centres of bright gold, some of thicker quality, large, shell-like petals, almost ribbed in their effect, their green knob in the middle like a boss upon a shield, rayed about with beautiful grayish yellow stamens, as in the kind called the Bride. Others — they call this kind the Snowdrift — have thick double flowers, deeply cut and fringed at the edges, the most opaque white, and full of exquisite shadows. Then there are the Icelanders, which Lieutenant Peary found making gay the frosty fields of Greenland, in buttercup-yellow and orange and white; the great Orientals, gorgeous beyond expression; the immense single white California variety. I could not begin to name them all in the longest summer's day! The Thorn Poppy, Argemone, is a fascinating variety, most quaint in method of growth and most decorative. As for the Shirleys, they are children of the dawn, and inherit all its delicate, vivid, delicious suffusions of rose-color in every conceivable shade. Of the Poppy one of the great masters of English prose discourses in this wise. Speaking of the common wild Poppy of the English fields, which grows broadcast also over most of Europe, he says: " The splendor of it is proud, almost insolently so," which immediately brings to mind Browning 's lines in "Sordello," —

"The

Poppy's red

effrontery,

Till autumn spoils its fleering quite with rain, And portionless, a dry, brown, rattling crane Protrudes."

Poppy Bank in the Early Morning Papaver Rhśas is the common wild scarlet Poppy that both these writers describe. John Ruskin says: "I have in my hand a small red Poppy which I gathered on Whit Sunday in the palace of the Cćsars. It is an intensely simple, intensely floral flower. All silk and flame, a scarlet cup, perfect edged all round, seen among the wild grass far away like a burning coal fallen from Heaven's altars. You cannot have a more complete, a more stainless type of flower absolute; inside and outside, all flower. No sparing of color anywhere, no outside coarsenesses, no interior secrecies, open as the sunshine that creates it; fine finished on both sides, down to the extremest point of insertion on its narrow stalk, and robed in the purple of the Cćsars. . . . "Literally so. That Poppy scarlet, so far as could be painted by mortal hand, for mortal king, stays yet, against the sun and wind and rain, on the walls of the house of Augustus, a hundred yards from the spot where I gathered the weed of its desolation. . . . The flower in my hand is a poverty stricken Poppy, I was going to write, poverty strengthened Poppy, I mean. On richer ground it would have gushed into flaunting breadth of untenable purple; flapped its inconsistent scarlet vaguely to the wind; dropped the pride of its petals over my hand in an hour after I gathered it. But this little rough-bred thing . . . is as bright and strong to-day as yesterday. . . . What outline its petals really have is little shown in their crumpled fluttering, but that very crumpling arises from a fine floral character which we do not enough value in them. We usually think of a Poppy as a coarse flower; but it is the most transparent and delicate of all the blossoms of the field. The rest, nearly all of them, depend on the texture of their surfaces for color. But the Poppy is painted glass; it never glows so brightly as when the sun shines through it. Wherever it is seen, against the light or with the light, always it is a flame, and warms the wind like a blown ruby. . . . Gather a green Poppy bud, just when it shows the scarlet line at its side, break it open and unpack the Poppy. The whole flower is there complete in size and color, its stamens full grown, but all packed so closely that the fine silk of the petals is crushed into a million of wrinkles. When the flower opens, it seems a relief from torture; the two imprisoning green leaves are shaken to the ground, the aggrieved corolla smooths itself in the sun and comforts itself as best it can, but remains crushed and hurt to the end of its days." I know of no flower that has so many charming tricks and manners, none with a method of growth more picturesque and fascinating, The stalks often take a curve, a twist from some current of air or some impediment, and the fine stems will turn and bend in all sorts of graceful ways, but the bud is always held erect when the time comes for it to blossom. Ruskin quotes Lindley's definition of what constitutes a Poppy, which he thinks "might stand." This is it: "A Poppy is a flower which has either four or six petals, and two or more treasuries united in one, containing a milky, stupefying fluid in its stalks and leaves, and always throwing away its calyx when it blossoms." I muse over their seed-pods, those supremely graceful urns that are wrought with such matchless elegance of shape, and think what strange power they hold within. Sleep is there, and Death his brother, imprisoned in those mystic sealed cups. There is a hint of their mystery in their shape of sombre beauty, but never a suggestion in the fluttering blossom; it is the gayest flower that blows. In the more delicate varieties the stalks are so slender, yet so strong, like fine grass stems, when you examine them you wonder how they hold even the light weight of the flower so firmly and proudly erect. They are clothed with the finest of fine hairs up and down the stalks, and over the green calyx, especially in the Iceland varieties, where these hairs are of a lovely red-brown color and add much to their beauty. It is plain to see, as one gazes over the Poppy beds on some sweet evening at sunset, what buds will bloom in the joy of next morning's first sunbeams, for these will be lifting themselves heavenward, slowly and silently, but surely. To stand by the beds at sunrise and see the flowers awake is a heavenly delight. As the first long, low rays of the sun strike the buds, you know they feel the signal! A light air stirs among them; you lift your eyes, perhaps to look at a rosy cloud or follow the flight of a caroling bird, and when you look back again, lo the calyx has fallen from the largest bud and lies on the ground, two half transparent, light green shells, leaving the flower petals wrinkled in a thousand folds, just released from their close pressure. A moment more and they are unclosing before your eyes. They flutter out on the gentle breeze like silken banners to the sun, and such a color! The orange of the Iceland Poppy is the most ineffable color; it "warms the wind" indeed I know no tint like it; it is orange dashed with carmine, most like the reddest coals of an intensely burning fire. Look at this exquisite cup: the wind has blown nearly smooth the crinkled petals; these, where they meet in the centre, melt into a delicate greenish yellow. In the heart of the blossom rises a round green altar, its sides penciled with nine black lines, and a nine-rayed star of yellow velvet clasps the flat, pure green top. From the base of this altar springs the wreath of stamens and anthers; the inner circle of these is generally white, the outer yellow, and all held high and clear within the cup. The radiant effect of this arrangement against the living red cannot be told. The Californias put out their clean, polished, pointed buds straight up to the sun from the first, but all the others have this fashion of drooping theirs till the evening before they blow. There is a kind of triumph in the way they do this, lifting their treasured splendor yet safe within its clasping calyx to be ready to meet the first beams of the day. The Orientals are glorious, even in the victorious family of Poppies. Ruskin has a chapter on "The Rending of Leaves." I always think of it when I see the large, hairy, rich green leaves of this variety, which are deeply "rent," almost the whole width of the leaf to the midrib. These leaves grow somewhat after the fashion of a Dandelion, spreading several feet in all directions from the centre, which sends up in June immense flower-stalks crowned with heavy apple-like buds, that elongate as they increase in size, till some morning the thick calyx breaks and falls, and the great scarlet flags of the flower unfold. There is a kind of angry brilliance about it, a sombre and startling magnificence. Its large petals are splashed near the base with broad, irregular spots of black-purple, as if they had been struck with a brush full of color. The seed-pod, rising fully an inch high in the centre, is of a luminous, indescribable shade of green, and folded over its top, a third of its height, is a cap of rich lavender, laid down in points evenly about the crown. On the centre of this is a little knob of deep purple velvet, from which eleven rays of the same color curve over the top and into each point of the lavender cap. And round this wonderful seed-pod, with its wealth of elaborate ornament, is a thick girdle of stamens half an inch deep, with row upon row and circle within circle of anthers covered with dust of splendid dusky purple, and held each upon a slender thread of deeper purple still. It is simply superb, and when the great bush is ablaze with these flowers it is indeed a conflagration of color. "The fire-engines always turn out when my Orientals blaze up on the hillside," writes a flower-loving friend to me. No garden should be without these, for they flourish with the least care, are perfectly hardy, and few fail to blossom generously. |