| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2009 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

THAT every plant should select only its own colors and forms from the great laboratory of Nature has always seemed to me a very wonderful thing. Each plant takes from its surroundings just those qualities which will produce its own especial characteristics and no others, never hesitating and never making a mistake. For instance, the California Poppies, if left to themselves, will take yellow of many resplendent shades for their color, and never vary their cool, gray-green, red-tipped foliage; the Peacock Poppy will be always scarlet-crimson, with a black spot rimmed with white in every petal; the Corn Poppy will be always clear scarlet; the Bride a miracle of lustrous white, and so on. Runge, a noted chemist, says: "A plant is a great chemist: it distinguishes and separates substances more definitely and accurately than man can, with all his skill, his intelligence, and his appliances. . . . The little Daisy, which has painted its 'wee crimson-tipped flowers,' puts the chemist and scientific man to shame, for it has produced its leaf and stem and flowers, and has dyed these with their bright colors from materials which he can never change with all his arts." By what power do they know how to select each its own hue and shape, when earth and air hold all the tints and forms that the Creator has invented? The subtle knowledge of plants, instinct perhaps would be a better word, is astonishing. If you dig a hole in the ground and put into it a Rosebush, filling one side of the hole with rich earth and the other with poor soil, every root of that Rosebush will leave the poor half to inhabit the rich and nourishing portion. That is a matter of course, but the instinct of the Rose is something to think about, nevertheless. Some one has said, speaking of a tree, "What an immense amount of vitally organized material has been here gathered together! It is God's own architecture This mass of vegetable matter is only earth and air that have undergone transmutation. The material alike of wandering zephyrs and rushing storms, of gently descending night-dews and angry thunder-showers has been here, on this spot, metamorphosed." And I should add that into this piece of architecture God has breathed a vital spark, almost a mind, so remarkable is the intelligent action often manifested in many plants and trees. A famous Frenchman, Camille Flammarion, says: "I know a maple-tree which was dying on the ruins of an old wall, a few feet from good rich earth (the soil in a ditch), and which in despair threw out a venturesome root, reached the coveted earth, buried itself there, and gained a solid footing, so that by degrees, although a motionless thing, it changed its place, let its original roots die, and lived resuscitated upon the organ that had set it free. I have known elms which were going to eat up the soil of a fertile field, whose food had been cut off from them by a wide ditch, and who, therefore, determined to make their uncut roots pass under the ditch. They succeeded, and returned to their regular food, much to the cultivator's astonishment. I know an heroic Jasmine which went eight times through a board which kept the light away from it, and which a teasing observer would put back in the shade, hoping so to wear out the flower's energy, but he did not succeed." This happened in France, but here in New England I myself know of a great Wistaria which grew over one side of a fine old house in an enchanting garden, and which did something quite as wonderful. It was a triumph of a vine! The butt or stump, where it emerged from the ground, was a foot in diameter, and its branches covered one side of the house, a space of thirty feet by thirty feet. So large a vine required a great deal of water, so it sent its roots down eight feet under the foundation of the house, passed along under the brick floor of the dairy, a distance of fifteen feet, making a solid mat of roots under the whole floor, reached the well and went straight through the cracks and crevices of its stone wall to the desired moisture. An elm root in the same garden went sixty feet or more under the foundation of the house to that same well. To quote another writer who has carefully observed these things: "Plants have to the full extent of their necessities a power of observation, of discrimination in the selection of their food, a knowledge of where it is to be found, and the power to a considerable extent to obtain it. For instance, if some animal's remains are buried in the garden, say twenty feet from the grapevine, the vine will know it, and the underground part of the vine will at once change its course and make a direct march for this new storehouse of food, and upon reaching it will throw out an in- credible number of roots for its consumption. . . . A weeping willow was planted in a dry, gravelly soil on the south side of a house, a situation in every respect unsuited to this tree, which delights in a heavy moist soil; the result Was a slow, stunted growth. After a few years in which it barely lived, it surprised its owner by a vigorous growth which was as astonishing as pleasing, and the cause was looked for. It was found the roots in search of food had traveled under the house a distance of some thirty feet to the well, where they took a downward course till they reached the water that furnished the moisture which is essential to the growth of this tree. "The movements of the squash vine when pressed by hunger or thirst are truly wonderful. During a severe drought if you place a basin of water at night, say two feet to the left or the right of a strong vine, in the morning it will be found bathing in the basin! Is not this an indication of thought in the vine? Does it not indicate a knowledge in the vine analogous to human understanding? . . . There must be some agent employed to bring the vine to the fountain. . . . "The more we study plant life the more we be- come convinced that life is a unit, varying in form only, not in principle. Everything capable of reproduction, growth, and development is governed by the same law, and each is but a part of the unit we term life." Again to quote the famous Frenchman: "When breathe the perfume of a Rose," he says, " when I admire the beauty of form, the grace of this flower in its freshly opening bloom, what strikes me most is the work of that hidden, unknown, mysterious force which rules over the plant's life and can direct it in the maintenance of its existence, which chooses the proper molecules of air, water, and earth for its nourishment, and which knows, above all, how to assimilate these molecules and group them so delicately as to form this graceful stem, these dainty green leaves, these soft pink petals, these exquisite tints and delicious fragrance: . . . "This mysterious force is the animating principle of the plant. Put a Lily seed, an acorn, a grain of wheat, and a peach-stone side by side in the ground, each germ will build up its own organism and no other. . . . "A plant breathes, drinks, eats, selects, refuses, seeks, works, lives, acts, according to its instincts. One does like a charm, another pines, a third is nervous and agitated. The Sensitive Plant shivers and droops its leaves at the slightest touch." Climbing plants show often a surprising degree of intelligence, reaching out for support as if they had eyes to see. I have known a vine whose head was aimlessly waving in the wind, with nothing near it to which it might cling, turn deliberately round in an opposite direction to that in which it had been growing and seize a line I had stretched for it to grasp, without any help outside itself, and within the space of an hour's time. By manifold ways they cling and climb, many by winding their stems round and round strings or sticks or wires, or whatever is given them, as do the Morning-glories, Hop, Honeysuckle, Wistarias, and many others; but Sweet Peas, Cobœa, and so forth, put out a delicate tendril at the end of each leaf, or rather group of leaves. Nasturtiums, Clematis, and others take a turn with their leaf-stems round anything that comes in their way, and so lift and hold themselves securely, and the Echinocystus or Wild Cucumber has a system of tendrils strong as iron and elastic as India-rubber. It is most interesting to observe them all and ponder on their different charming ways and habits, to help them if they need it, and to sympathize with all their experiences. As I work among my flowers, I find myself talking to them, reasoning and remonstrating with them, and adoring them as if they were human beings. Much laughter I provoke among my friends by so doing, but that is of no consequence. We are on such good terms, my flowers and I!  The Altar and Shrine Altogether lovely they are out of doors, but I plant and tend them always with the thought of the joy they will be within the house also. I know well what Emerson means when he asks, "Hast

thou named all the birds without a gun?

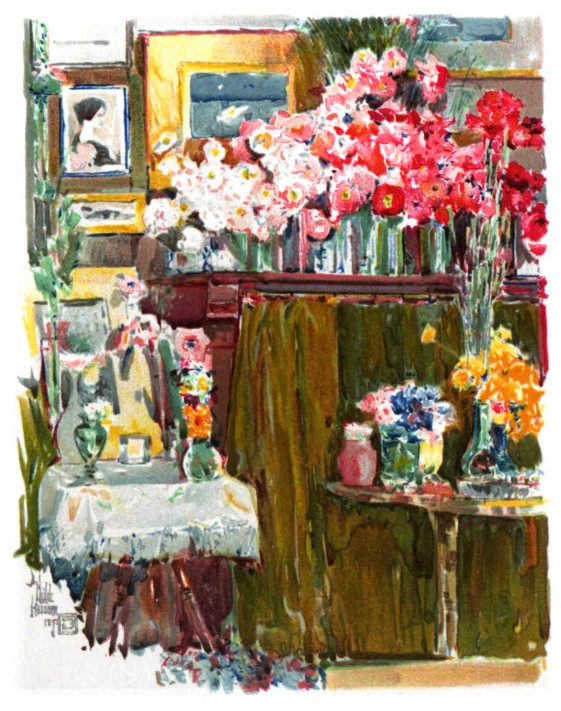

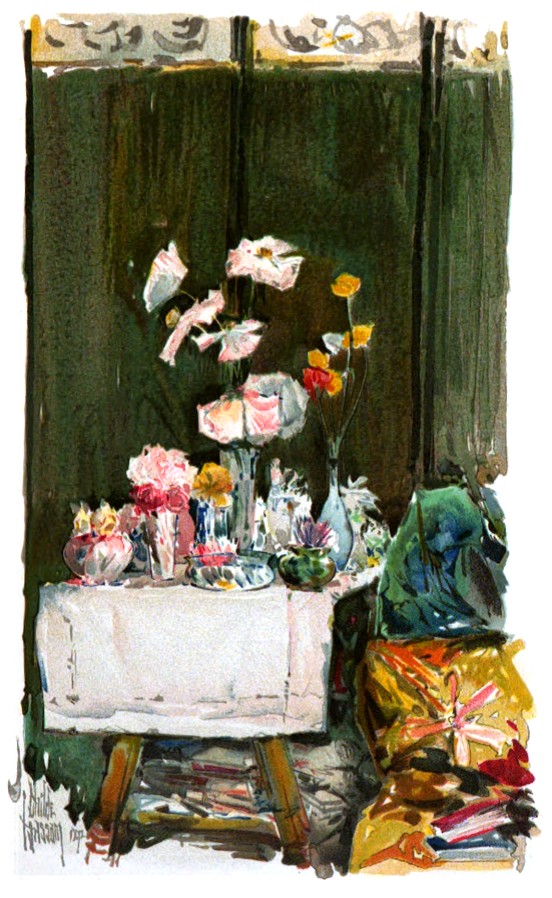

Loved the wood Rose and left it on its stalk?" and if I gather this or any other wild-flower I do it with such reverent love that even he would be satisfied. No one knows better and deplores more deeply than I the wholesale destruction, wanton and cruel, which goes on among our wildflowers every year; but to bring a few indoors for purposes of study and fuller appreciation is another and a desirable thing. For the wild Rose is but partially learned when one pauses a moment in passing to admire the sweet surprise of its beauty as it suddenly smiles up from the roadside. It cannot be learned in a single glance, nor, indeed, in many glances: it must be carefully considered and lovingly meditated upon before it yields all the marvel of its delicate glory to your intelligence. "Consider the Lilies," said the Master. Truly, there is no more prayerful business than this "consideration" of all the flowers that grow. And in the garden they are planted especially to feast the souls that hunger for beauty, and within doors as well as without they "delight the spirit of man." Opening out on the long piazza over the flower beds, and extending almost its whole length, runs the large, light, airy room where a group of happy people gather er to pass the swiftly flying summers here at the Isles of Shoals. This room is made first for music; on the polished floor is no carpet to muffle sound, only a few rugs here and there, like patches of warm green moss on the pine-needle color given by the polish to the natural hue of the wood. There are no heavy draperies to muffle the windows, nothing to absorb the sound. The piano stands midway at one side; there are couches, sofas with pillows of many shades of dull, rich color, but mostly of warm shades of green. There are low bookcases round the walls, the books screened by short curtains of pleasant olive-green; the high walls to the ceiling are covered with pictures, and flowers are everywhere. The shelves of the tall mantel are splendid with massed Nasturtiums like a blazing torch, beginning with the palest yellow, almost white, and piled through every deepening shade of gold, orange, scarlet, crimson, to the blackest red; all along the tops of the low bookcases burn the fires of Marigolds, Coreopsis, large flowers of the velvet single Dahlias in yellow, flame, and scarlet of many shades, masses of pure gold summer Chrysanthemums, and many more, — all here and there interspersed with blossoming grasses for a touch of ethereal green. On one low bookcase are Shirley Poppies in a roseate cloud. And here let me say that the secret of keeping Poppies in the house two whole days without fading is this: they must be gathered early, before the dew has dried, in the morning. I go forth between five and six o'clock to cut them while yet their gray-green leaves are hoary with dew, taking a tall slender pitcher or bottle of water with me into the garden, and as I cut each stem dropping the flower at once into it, so that the stem is covered nearly its whole length with water; and so on till the pitcher is full. Gathered in this way, they have no opportunity to lose their freshness, indeed, the exquisite creatures hardly know they have been gathered at all. When I have all I need, I begin on the left end of this bookcase, which most felicitously fronts the light, and into the glasses put the radiant blossoms with an infinite enjoyment of the work. The glasses (thirty-two in all) themselves are beautiful: nearly all are white, clear and pure, with a few pale green and paler rose and delicate blue, one or two of richer pink, all brilliantly clear and filled with absolutely colorless water, through which the stems show their slender green lengths. Into the glasses at this end on the left I put first the dazzling white single Poppy, the Bride, to lead the sweet procession, — a marvelous blossom, whose pure white is half transparent, with its central altar of ineffable green and gold. A few of these first, then a dozen or more of delicate tissue-paperlike blossoms of snow in still another variety (with petals so thin that a bright color behind them shows through their filmy texture); then the double kind called Snowdrift, which being double makes a deeper body of whiteness flecked with softest shadow. Then I begin with the palest rose tints, placing them next, and slightly mingling a few with the last white ones, — a rose tint delicate as the palm of a baby's hand; then the next, with a faint suffusion of a blush, and go on to the next shade, still very delicate, not deeper than the soft hue on the lips of the great whelk shells in southern seas; then the damask rose color and all tints of tender pink, then the deeper tones to clear, rich cherry, and on to glowing crimson, through a mass of this to burning maroon. The flowers are of all heights (the stems of different lengths), and, though massed, are in broken and irregular ranks, the tallest standing a little over two feet high. But there is no crushing or crowding. Each individual has room to display its full perfection. The color gathers, softly flushing from the snow white at one end, through all rose, pink, cherry, and crimson shades, to the note of darkest red; the long stems of tender green showing through the clear glass, the radiant tempered gold of each flower illuminating the whole. Here and there a few leaves, stalks, and buds (if I can bring my mind to the cutting of these last) are sparingly interspersed at the back. The effect of this arrangement is perfectly beautiful. It is simply indescribable, and I have seen people stand before it mute with delight. It is like the rose of dawn. To the left of this altar of flowers is a little table, upon which a picture stands and leans against the wall at the back. In the picture two Tea Roses long since faded live yet in their exquisite hues, never indeed to die. Before this I keep always a few of the fairest flowers, and call this table the shrine. Sometimes it is a spray of Madonna Lilies in a long white vase of ground glass, or beneath the picture in a jar of yellow glass floats a saffron-tinted Water Lily, the Chromatella, or a tall sapphire glass holds deep blue Larkspurs of the same shade, or in a red Bohemian glass vase are a few carmine Sweet Peas, another harmony of color, or a charming dull red Japanese jar holds a few Nasturtiums that exactly repeat its hues. The lovely combinations and contrasts of flowers and vases are simply endless. On another small table below the "altar" are pink Water Lilies in pink glasses and white ones in white glasses; a low basket of amber glass is filled with the pale turquoise of Forget-me-nots, the glass is iridescent and gleams with changing reflections, taking tints from every color near it. Sweet Peas are everywhere about and fill the air with fragrance; orange and yellow Iceland Poppies are in tall vases of English glass of light green. There is a large, low bowl, celadon-tinted, and decorated with the boughs and fruit of the Olive on the gray-green background. This is filled with magnificent Jacqueminot Roses, so large, so deep in color as to fully merit the word. Sometimes they are mixed with pink Gabrielle de Luizets and old-fashioned Damask Roses, and the bowl is set where the light falls just as it should to give the splendor of the flowers its full effect. In the centre of a round table under one of the chandeliers is a flaring Venice glass as pure as a drop of dew and of a quaintly lovely shape; on the crystal water therein lies a single white Water Lily, fragrant snow and gold. By itself is a low vase shaped like a Magnolia flower, with petals of light yellow deepening in color at the bottom, where its calyx of olive-green leaves clasps the flower. This has looking over its edge a few pale yellow Nasturtiums of the Asa Gray variety, the lightest of all. With these, one or two of a richer yellow (Dunnett's Orange), the flowers repeating the tones of the vase, and with them harmoniously blending. A large pearly shell of the whelk tribe was given me years ago. I did not know what to do with it. I do not like flowers in shells as a rule, and I think the shells are best on the beach where they belong, but I was fond of the giver, so I sought some way of utilizing the gift. In itself it was beautiful, a mass of glimmering rainbows. I bored three holes in its edge and suspended it from one of the severely simple chandeliers with almost invisible wires. I keep it filled with water and in it arrange sometimes clusters of monthly Honeysuckle sparingly; the hues of the flowers and the shell mingle and blend divinely. I get the same effect with Hydrangea flowers, tints and tones all melt together; so also with the most delicate Sweet Peas, white, rose, and lilac; with these I take some lengths of the blossoming Wild Cucumber vine with its light clusters of white flowers, or the white Clematis, the kind called "Traveler's Joy," and weave it lightly about the shell, letting it creep over one side and, running up the wires, entirely conceal them; then it is like a heavenly apparition afloat in mid air. Sometimes the tender mauve and soft rose and delicate blues of the exquisite little Rose Campion, or Rose of Heaven, with its grassy foliage, swing in this rainbow shell, making another harmony of hues. Sometimes it is draped with wild Morning-glory vines which are gathered with their buds at evening; their long wiry stems I coil in the water, and arrange the graceful lengths of leaves and buds carefully, letting a few droop over the edge and twine together beneath the shell, and some run up to the chandelier and conceal the wires. The long smooth buds, yellow-white like ivory, deepen to a touch of bright rose at the tips close folded. In the morning all the buds open into fair trumpets of sea-shell pink, turning to every point of the compass, an exquisite sight to see. By changing the water daily these vines last a week, fresh buds maturing and blossoming every morning. Near my own seat in a sofa corner at one of the south windows stands yet another small table, covered with a snow-white linen cloth embroidered in silk as white and lustrous as silver. On this are gathered every day all the rarest and loveliest flowers as they blossom, that I may touch them, dwell on them, breathe their delightful fragrance and adore them. Here are kept the daintiest and most delicate of the vases which may best set off the flowers' loveliness, — the smallest of the collection, for the table is only large enough to hold a few. There is one slender small tumbler of colorless glass, from the upper edge of which a crimson stain is diffused half way down its crystal length. In this I keep one glowing crimson Burgundy Rose, or an opening Jacqueminot bud; the effect is as if the color of the rose ran down and dyed the glass crimson. It is so beautiful an effect one never wearies of it. There is a little jar of Venice glass, the kind which Browning describes in "The Flight of the Duchess,"

"With long white threads distinct

inside,

Like the lake-flower's fibrous roots that dangle Loose such a length and never tangle."

This is charming with a few rich Pinks of different shades. Another Venice glass is irregularly bottle-shaped, bluish white with cool sea-green reflections at the bottom, very delicate, like an aqua-marine. It is lightly sprinkled with gold dust throughout its whole length; toward the top the slender neck takes on a soft touch of pink which meets and mingles with the Bon Silene or La France Rose I always keep in it. Another Venice glass still is a wonder of iridescent blues,. lavenders, gray, and gold, all through, with a faint hint of elusive green. A spray of heaven-blue Larkspur dashed with rose is delicious in this slender shape, with its marvelous tints melting into the blue and pink of the fairy flowers.  A Favorite Corner A little glass of crystal girdled with gold holds pale blue Forget-me-nots; sometimes it is rich with orange and yellow Erysimum flowers. In a tall Venetian vase of amber a Lilium auratum is superb. A low jar of opaque rose-pink, lost at the bottom in milky whiteness, is refreshing with an old-fashioned Damask Rose matching its color exactly. This is also exquisite with one pink Water Lily. The pink variety ot the Rose Campion is enchanting in this low jar. A tall shaft of ruby glass is radiant with Poppies; of every shade of rose and lightest scarlet, with the green of a few oats among them. A slender purple glass is fine with different shades of purple and lilac Sweet Peas, or one or two purple Poppies, or an Aster or two of just its color, but there is one long gold-speckled Bohemian glass of rich green which is simply perfect for any flower that blows, and perfect under any circumstances. A half dozen Iceland Poppies, white, yellow, orange, in a little Japanese porcelain bottle, always stand on this beautiful table, the few flecks of color on the bottle repeating their tints. I never could tell half the lovely combinations that glow on this table all summer long. By the wide western window a large vase of clear white glass, nearly three feet high, stands full of spears of timothy grass taller than the vase, the tallest I can find, springing stately and high, their heavy green tops bending the fine strong stems just enough for consummate grace. These are mixed with lighter branching grasses, and down among the grass stalks are thrust the slender stalks of tall Poppies of every conceivable shade of red; the whole is a great sheaf of splendor reaching higher than the top of the window. This is really imposing; it takes the eye with delight. All summer long within this pleasant room the flowers hold carnival in every possible combination of beauty. All summer long it is kept fresh and radiant with their loveliness — a wonder of bloom, color, and fragrance. Year after year a long procession of charming people come and go within its doors, and the flowers that glow for their delight seem to listen with them to the music that stirs each blossom upon its stem. Often have I watched the great red Poppies drop their fiery petals wavering solemnly to the floor, stricken with arrows of melodious sound from the matchless violin answering to the touch of a master, or to the storm of rich vibrations from the piano. What heavenly music has resounded from those walls, what mornings and evenings of pleasantness have flown by in that room! How many people who have been happy there have gone out of it and of the world forever! Yet still the summers come, the flowers bloom, are gathered and adored, not without wistful thought of the eyes that will see them no more. Still in the sweet tranquil mornings at the piano one sits playing, also with a master's touch, and strains of Schubert, Mozart, Schumann, Chopin, Rubinstein, Beethoven, and many others, soothe and enchant the air. The wild bird's song that breaks from without into the sonata makes no discord. Open doors and windows lead out on the vine-wreathed veranda, with the garden beyond steeped in sunshine, a sea of exquisite color swaying in the light air. Poppies blowing scarlet in the wind, or delicately flushing in softest rose or clearest red, or shining white where the Bride stands tall and fair, like a queen among them all. A thousand varied hues amid the play of fluttering leaves: Marigolds ablaze in vivid flame; purple Pansies, — a myriad flowers, white, pink, blue, carmine, lavender, in waves of sweet color and perfume to the garden fence, where stand the sentinel Sunflowers and Hollyhocks, gorgeously arrayed and bending gently to the breeze; Sunflowers with broad faces that seem to reflect the glory of the day; the Hollyhocks, tall spikes of pale and deep pink, white, scarlet, yellow, maroon, and many hues. Over the sweet sea of flowers the butterflies go wavering on airy wings of white and gold, the bees hum in the Hollyhocks, and the humming-birds glitter like jewels in the sun; but whether these their winged lovers go or come, the flowers do not care, they live their happy lives and rejoice, intent only on fulfilling Heaven's will, to grow and to blossom in the utmost perfection possible to them. Climbing the trellis, the monthly Honeysuckle holds its clusters high against the pure sunlit sky, glowing in beauty beyond any words of mine to tell. Charming people sit within the pleasant room among its flowers, listening to the delicious music; others are grouped without in the sun-flecked shadow of the green vines, where the cool air ripples lightly in the leaves; lovely women in colors that seem to have copied the flowers in the garden, and all steeped in sweet dreams and fugitive fancies as delicate as the perfumes that drift in soft waves from the blossoms below. Beyond the garden the green grassy spaces sloping to the sea are rich with blossoming thickets of wild Roses, among the bleached white ledges, blushing fair to see, and the ocean beyond shimmers and sparkles beneath the touch of the warm south wind. Enchanting days, and evenings still more so, if that were possible! With the music still thrilling within the lighted room where the flowers glow under the lamplight, while floods of moonlight make more mystic the charmed night without. The thick curtain of the green vine that drapes the piazza is hung over its whole surface with the long drooping clusters of its starry flowers that lose all their sweetness upon the air, and show from the garden beneath like an immense airy veil of delicate white lace in the moonlight, — a wonderful white glory. Through the windows cut in this living curtain of leaves, and flowers we look out over the sea beneath the moon — is anything more mysteriously beautiful? — on glimmering waves and shadowy sails and rocks dim in broken light and shade; on the garden with all its flowers so full of color that even in the moonlight their hues are visibly glowing. The fair creatures stand still, unstirred by any wandering airs, the Lilies gleam, and the white stars of the Nicotiana, the white Poppies, the white Asters that just begin to bloom, and the tall milky clusters of the Phlox: nothing disturbs their slumber save perhaps the wheeling of the rosy-winged Sphinx moth that flutters like the spirit of the night above them as they dream. |