| Web and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2016 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER VII. After what manner the Pirates arm their vessels, and how they regulate their voyages. BEFORE the Pirates go out to sea, they give notice to every one that goes upon the voyage, of the clay on which they ought precisely to embark, intimating also to them their obligation of bringing each man in particular so many pounds of powder and bullets as they think necessary for that expedition. Being all come on board, they join together in council, concerning what place they ought first to go to wherein to get provisions — especially of flesh, seeing they scarce eat anything else. And of this the most common sort among them is pork. The next food is tortoises, which they are accustomed to salt a little. Sometimes they resolve to rob such or such hog-yards, wherein the Spaniards often have a thousand heads of swine together. They come to these places in the dark of the night, and having beset the keeper's lodge, they force him to rise, and give them as many heads as they desire, threatening withal to kill him in case he disobeys their commands or makes any noise. Yea, these menaces are oftentimes put in execution, without giving any quarter to the miserable swine-keepers, or any other person that endeavours to hinder their robberies. Having got provisions of flesh sufficient for their voyage, they return to their ship. Here their allowance, twice a day to every one, is as much as he can eat, without either weight or measure. Neither does the steward of the vessel give any greater proportion of flesh, or anything else to the captain than to the meanest mariner. The ship being well victualled, they call another council, to deliberate towards what place they shall go, to seek their desperate fortunes. In this council, likewise, they agree upon certain Articles, which are put in writing, by way of bond or obligation, which every one is bound to observe, and all of them, or the chief, set their hands to it. Herein they specify, and set down very distinctly, what sums of money each particular person ought to have for that voyage, the fund of all the payments being the common stock of what is gotten by the whole expedition; for otherwise it is the same law, among these people, as with other Pirates, No prey, no pay. In the first place, therefore, they mention how much the Captain ought to have for his ship. Next the salary of the carpenter, or shipwright, who careened, mended and rigged the vessel. This commonly amounts to one hundred or an hundred and fifty pieces of eight,1 being, according to the agreement, more or less. Afterwards for provisions and victualling they draw out of the same common stock about two hundred pieces of eight. Also a competent salary for the surgeon and his chest of medicaments, which usually is rated at two hundred or two hundred and fifty pieces of eight. Lastly they stipulate in writing what recompense or reward each one ought to have, that is either wounded or maimed in his body, suffering the loss of any limb, by that voyage. Thus they order for the loss of a right arm six hundred pieces of eight, or six slaves; for the loss of a left arm five hundred pieces of eight, or five slaves; for a right leg five hundred pieces of eight, or five slaves; for the left leg four hundred pieces of eight, or four slaves; for an eye one hundred pieces of eight, or one slave; for a finger of the hand the same reward as for the eye. All which sums of money, as I have said before, are taken out of the capital sum or common stock of what is got by their piracy. For a very exact and equal dividend is made of the remainder among them all. Yet herein they have also regard to qualities and places. Thus the Captain, or chief Commander, is allotted five or six portions to what the ordinary seamen have; the Master's Mate only two; and other Officers proportionate to their employment. After whom they draw equal parts from the highest even to the lowest mariner, the boys not being omitted. For even these draw half a share, by reason that, when they happen to take a better vessel than their own, it is the duty of the boys to set fire to the ship or boat wherein they are, and then retire to the prize which they have taken. They observe among themselves very good orders. For in the prizes they take, it is severely prohibited to every one to usurp anything in particular to themselves. Hence all they take is equally divided, according to what has been said before. Yea, they make a solemn oath to each other not to abscond, or conceal the least thing they find amongst the prey. If afterwards any one is found unfaithful, who has contravened the said oath, immediately he is separated and turned out of the society. Among themselves they are very civil and charitable to each other Insomuch that if any wants what another has, with great liberality they give it one to another. As soon as these Pirates have taken any prize of ship or boat, the first thing they endeavour is to set on shore the prisoners, detaining only some few for their own help and service, to whom also they give their liberty after the space of two or three years. They put in very frequently for refreshment at one island or another; but more especially into those which lie on the Southern side of the Isle of Cuba. Here they careen their vessels, and in the meanwhile some of them go to hunt, others to cruize upon the seas in canoes, seeking their fortune. Many times they take the poor fishermen of tortoises, and, carrying them to their habitations, they make them work so long as the Pirates are pleased. In the several parts of America are found four distinct species of tortoises. The first hereof are so great that every one reaches the weight of two or three thousand pounds. The scales of the species are so soft that they may easily be cut with a knife. Yet these tortoises are not good to be eaten. The second species is of an indifferent bigness, and are green in colour. The scales of these are harder than the first, and this sort is of a very pleasant taste. The third is very little different in size and bigness from the second, unless that it has the head something bigger. This third species is called by the French cavana, and is not good for food. The fourth is named caret, being very like the tortoises we have in Europe. This sort keeps most commonly among the rocks, whence they crawl out to seek their food, which is for the greatest part nothing but apples of the sea. These other species above-mentioned feed upon grass, which grows in the water upon the banks of sand. These banks or shelves, for their pleasant green, resemble the delightful meadows of the United Provinces. Their eggs are almost like those of the crocodile, but without any shell. being only covered with a thin membrane or film. They are found in such prodigious quantities along the sandy shores of those countries, that, were they not frequently destroyed by birds, the sea would infinitely abound with tortoises. These creatures have certain customary places whither they repair every year to lay their eggs. The chief of these places are the three islands called Caymanes, situated in the latitude of twenty degrees and fifteen minutes North, being at the distance of five and forty leagues from the Isle of Cuba, on the Northern side thereof. It is a thing much deserving consideration how the tortoises can find out these islands. For the greatest part of them come from the Gulf of Honduras, distant thence the whole space of one hundred and fifty leagues. Certain it is, that many times the ships, having lost their latitude through the darkness of the weather, have steered their course only by the noise of the tortoises swimming that way, and have arrived at those isles. When their season of hatching is past, they retire towards the Island of Cuba, where are many good places that afford them food. But while they are at the Islands of Caymanes, they eat very little or nothing. When they have been about the space of one month in the seas of Cuba, and are grown fat, the Spaniards go out to fish for them, they being then to be taken in such abundance that they provide with them sufficiently their cities, towns and villages. Their manner of taking them is by making with a great nail a certain kind of dart. This they fix at the end of a long stick or pole, with which they wound the tortoises, as with a dagger, whensoever they appear above water to breathe fresh air. The inhabitants of New Spain and Campeche lade their principal sorts of merchandises in ships of great bulk; and with these they exercise their commerce to and fro. The vessels from Campeche in winter time set out towards Caracas, Trinity Isles and Margarita. For in summer the winds are contrary, though very favourable to return to Campeche, as they are accustomed to do at the beginning of that season. The Pirates are not ignorant of these times, being very dextrous in searching out all places and circumstances most suitable to their designs. Hence in the places and seasons aforementioned, they cruize upon the said ships for some while. But in case they can perform nothing, and that fortune does not favour them with some prize or other, after holding a council thereupon, they commonly enter-prize things very desperate. Of these their resolutions I shall give you one instance very remarkable. One certain Pirate, whose name was Pierre Francois, or Peter Francis, happened to be a long time at sea with his boat and six and twenty persons, waiting for the ships that were to return from Maracaibo towards Campeche. Not being able to find anything, nor get any prey, at last he resolved to direct his course to Rancherias, which is near the river called De la Plata, in the latitude of twelve degrees and a half North. In this place lies a rich bank of pearl, to the fishery whereof they yearly send from Cartagena a fleet of a dozen vessels, with a man-of-war for their defence. Every vessel has at least a couple of negroes in it, who are very dextrous in diving, even to the depth of six fathoms within the sea, whereabouts they find good store of pearls. Upon this fleet of vessels, though small, called the Pearl Fleet, Pierre Francois resolved to adventure, rather than go home with empty hands. They rode at anchor, at that time, at the mouth of the river De la Hacha, the man-of-war being scarce half a league distant from the small ships, and the wind very calm. Having espied them in this posture, he presently pulled down his sails and rowed along the coast, dissembling to be a Spanish vessel that came from Maracaibo, and only passed that way. But no sooner was he come to the Pearl Bank, than suddenly he assaulted the Vice-Admiral of the said fleet, mounted with eight guns and threescore men well armed, commanding them to surrender. But the Spaniards, running to their arms, did what they could to defend themselves, fighting for some while; till at last they were constrained to submit to the Pirate. Being thus possessed of the Vice-Admiral, he resolved next to adventure with some other stratagem upon the man-of-war, thinking thereby to get strength sufficient to master the rest of the fleet. With this intent he presently sank his own boat in the river, and, putting forth the Spanish colours, weighed anchor, with a little wind, which then began to stir, having with promises and menaces compelled most of the Spaniards to assist him in his design. But no sooner did the man-of-war perceive one of his fleet to set sail than he did so too, fearing lest the mariners should have any design to run away with the vessel and riches they had on board. This caused the Pirates immediately to give over that dangerous enterprize, thinking themselves unable to encounter force to force with the said man-of-war that now came against them. Hereupon they attempted to get out of the river and gain the open seas with the riches they had taken, by making as much sail as possibly the vessel would bear. This being perceived by the man-of-war, he presently gave them chase. But the Pirates, having laid on too much sail, and a gust of wind suddenly arising, had their main-mast blown down by the board, which disabled them from prosecuting their escape. This

unhappy event much encouraged those that were in the man-of-war, they

advancing and g lining upon the Pirates every moment; by which means at

last they were overtaken. But these notwithstanding, finding

them-:;elves still with two and twenty persons sound, the rest being

either killed or wounded, resolved to defend themselves so long as it

were possible. This they performed very courageously for some while,

until being thereunto forced by the man-of-war, they were compelled to

surrender. Yet this was not done without Articles, which the Spaniards

were glad to allow them, as follows: That they should not use them as

slaves, forcing them to carry or bring stones, or employing them in

other labours, for three or four years, as they commonly employ their

negroes. But that they should set them on shore, upon free land,

without doing them any harm in their bodies. Upon these Articles they

delivered themselves, with all that they had taken, which was worth

only in pearls to the value of above one hundred thousand pieces of

eight, besides the vessel, provisions, goods and other things. All

which, being put together, would have made to this Pirate one of the

greatest prizes he could desire; which he would certainly have

obtained, had it not been for the loss of his main-mast, as was said

before.

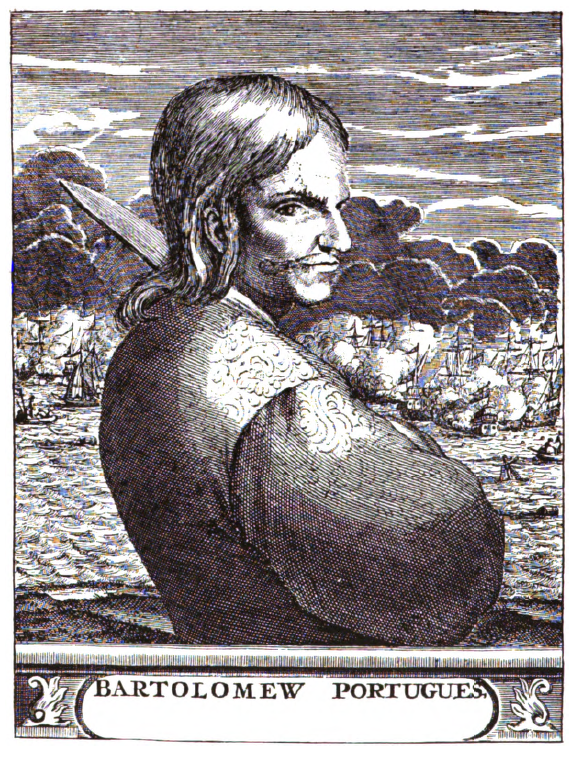

Another bold attempt, not unlike that which I have related, nor less remarkable, I shall also give you at present. A certain Pirate, born in Portugal, and from the name of his country called Bartholomew Portugues, was cruizing in his boat from Jamaica (wherein he had only thirty men and four small guns) upon the Cape de Corrientes, in the Island of Cuba. In this place he met with a great ship, that came from Maracaibo and Cartegena, bound for the Havana, well provided with twenty great guns and threescore and ten men, between passengers and mariners. This ship he presently assaulted, but found as strongly defended by them that were on board. The Pirate escaped .the first encounter, resolving to attack her more vigorously than before, seeing he had sustained no great damage hitherto. This resolution he boldly performed, renewing his assaults so often that after a long and dangerous fight he became master of the great vessel. The Portuguese lost only ten men and had four wounded, so that he had still remaining twenty fighting men, whereas the Spaniards had double that number. Having possessed themselves of such a ship, and the wind being contrary to return to Jamaica, they resolved to steer their course towards the Cape of Saint Antony (which lies on the Western side of the Isle of Cuba), there to repair themselves and take in fresh water, of which they had great necessity at that time. Being now very near the cape above-mentioned, they unexpectedly met with three great ships that were coming from New Spain and bound for the Havana. By these, as not being able to escape, they were easily retaken, both ship and Pirates. Thus they were all made prisoners, through the sudden change of fortune, and found themselves poor, oppressed, and stripped of all the riches they had pillaged so little before. The cargo of this ship consisted of one hundred and twenty thousand weight of cacao-nuts, the chief ingredient of that rich liquor called chocolate, and threescore and ten thousand pieces of eight. Two days after this misfortune, there happened to arise a huge and dangerous tempest, which largely separated the ships from one another. The great vessel wherein the Pirates were, arrived at Campeche, where many considerable merchants came to salute and welcome the Captain thereof. These presently knew the Portuguese Pirate, as being him who had committed innumerable excessive insolences upon those coasts, not only infinite murders and robberies, but also lamentable incendiums (i.e., fires), which the people of Campeche still preserved very fresh in their memory. Hereupon, the next day after their arrival, the magistrates of the city sent several of their officers to demand and take into custody the criminal prisoners from on board the ship, with intent to punish them according to their deserts. Yet fearing lest the Captain of those Pirates should escape out of their hands on shore (as he had formerly done, being once their prisoner in the city before), they judged it more convenient to leave him safely guarded on board the ship for the present. In the meanwhile they caused a gibbet to be erected, whereupon to hang him the very next day, without any other form of process than to lead him from the ship to the place of punishment. The rumour of this future tragedy was presently brought to Bartholomew Portugues' ears, whereby he sought all the means he could to escape that night. With this design he took two earthen jars, wherein the Spaniards usually carry wine from Spain to the West Indies, and stopped them very well, intending to use them for swimming, as those who are unskilful in that art do calabashes, a sort of pumpkins, in Spain, and in other places empty bladders. Having made this necessary preparation, he waited for the night, when all should be asleep, even the sentry that guarded him. But seeing he could not escape his vigilancy, he secretly secured a knife, and with the same gave him such a mortal stab as suddenly deprived him of life and the possibility of making any noise. At that instant he committed himself to sea, with those two earthen jars before-mentioned, and by their help and support, though never having learned to swim, he reached the shore. Being arrived upon land, without any delay he took refuge in the woods, where he hid himself for three days, without daring to appear nor eating any other food than wild herbs. Those of the city failed not the next day to make a diligent search for him in the woods, where they concluded him to be. This strict enquiry Portugues had the convenience to espy from the hollow of a tree, wherein he lay absconded. Hence perceiving them to return without finding what they sought for, he adventured to sally forth towards the coasts called Del Golfo Triste, forty leagues distant from the city of Campeche. Hither he arrived within a fortnight after his escape from the ship. In which space of time, as also afterwards, he endured extreme hunger, thirst, and fears of falling again into the hands of the Spaniards. For during all this journey he had no other provision with him than a small calabash, with a little water; neither did he eat anything else than a few shell-fish, which he found among the rocks near the sea-shore. Besides that, he was compelled to pass some rivers, not knowing well to swim. Being in this distress, he found an old board, which the waves had thrown upon the shore, wherein stuck a few great nails. These he took, and with no small labour whetted against a stone, until he had made them capable of cutting like knives, though very imperfectly. With these, and no better instruments, he cut down some branches of trees, which with twigs and osiers he joined together, and made as well as he could a boat, or rather a raft, wherewith he rafted over the rivers. Thus he arrived finally at the Cape of Golfo Triste, as was said before, where he happened to find a certain vessel of Pirates, who were great comrades of his own, and were lately come from Jamaica. To these Pirates he instantly related all his adversities and misfortunes, and withal demanded of them that they would fit him with a boat and twenty men. With which company alone he promised to return to Campeche and assault the ship that was in the river, which he had been taken by and escaped from fourteen days before. They readily granted his request, and equipped him a boat with the said number of men. With this small company he set forth towards the execution of his design, which he bravely performed eight days after he separated from his comrades at the Cape of Golfo Triste. For being arrived at the river of Campeche, with undaunted courage and without any rumour of noise he assaulted the ship before-mentioned. Those that were on board were persuaded this was a boat from land, that came to bring contraband goods; and hereupon were not in any posture of defence. Thus the Pirates, laying hold on this occasion, assaulted them without any fear of ill success, and in short space of time compelled the Spaniards to surrender. Being

now masters of the ship, they immediately weighed anchor and set sail,

determining to fly from the port, lest they should be pursued by other

vessels. This they did with extremity of joy, seeing themselves

possessors of such a brave ship. Especially Portugues, their captain,

who now by a second turn of Fortune's wheel was become rich and

powerful again, who had been so lately in that same vessel a poor

miserable prisoner and condemned to the gallows. With this great booty

he designed in his mind greater things; which he might well hope to

obtain, seeing he had found in the vessel great quantity of rich

merchandise still remaining on board, although the plate had been

transported into the city. Thus he continued his voyage towards Jamaica

for some days. But coming near the Isle of Pinos, on the South side of

the Island of Cuba, Fortune suddenly turned her back upon him once

more, never to show him her countenance again. For a horrible storm

arising at sea occasioned the ship to split against the rocks or banks

called Jardines. Insomuch that the vessel was totally lost, and

Portugues, with his companions, escaped in a canoe. After this manner

he arrived at Jamaica, where he remained no long time, being only there

till he could prepare himself to seek his fortune anew, which from that

time proved always adverse to him.

Nothing less rare and admirable than the preceding are the actions of another Pirate, who at present lives al. Jamaica, and who has on sundry occasions enterprized and achieved things very strange. The place of his birth was the city of Groningen, in the United Provinces; but his own proper name is not known: the Pirates, his companions, having only given him that of Roche Brasiliano by reason of his long residence in the country of Brazil, whence he was forced to flee, when the Portuguese retook those countries from the West India Company of Amsterdam, several nations then inhabiting at Brazil (as English, French, Dutch and others) being constrained to seek new fortunes. This fellow at that conjuncture of time retired to Jamaica, where being at a stand how to get a livelihood, he entered the Society of Pirates. Under these he served in quality of a private mariner for some while, in which degree he behaved himself so well that he was both beloved and respected by all, as one that deserved to be their Commander for the future. One day certain mariners happened to engage in a dissension with their Captain; the effect whereof was that they left the boat. Brasiliano followed the rest, and by these was chosen for their conductor and leader, who also fitted him out a boat or small vessel, wherein he received the title of Captain. Few days were past from his being chosen Captain, when he took a great ship that was coming from New Spain, on board of which he found great quantity of plate. and both one and the other he carried to Jamaica. This action gave him renown, and caused him to be both esteemed and feared, every one apprehending him much abroad. Howbeit, in his domestic and private affairs he had no good behaviour nor government over himself; for in these he would oftentimes shew himself either brutish or foolish. Many times being in drink, he would run up and down the streets, beating or wounding whom he met, no person daring to oppose him or make any resistance. To the Spaniards he always showed himself very barbarous and cruel, only out of an inveterate hatred he had against that nation. Of these he commanded several to be roasted alive upon wooden spits, for no other crime than that they would not shew him the places or hog-yards, where he might steal swine. After many of these cruelties, it happened as he was cruizing upon the coasts of Campeche, that a dismal tempest suddenly surprised him. This proved to be so violent that at last his ship was wrecked upon the coasts, the mariners only escaping with their muskets and some few bullets and powder, which were the only things they could save of all that was in the vessel. The place where the ship was lost was precisely between Campeche and the Golfo Triste. Here they got on shore in a canoe, and marching along the coast with all the speed they could, they directed their course towards Golfo Triste, as being a place where the Pirates commonly used to repair and refresh themselves. Being upon this journey and all very hungry and thirsty, as is usual in desert places, they were pursued by some Spaniards, being a whole troop of a hundred horsemen. Brasiliano no sooner perceived this imminent danger than he animated his companions, telling them: "We had better, fellow soldiers, choose to die under our arms fighting, as becomes men of courage, than surrender to the Spaniards, who, in case they overcome us, will take away our lives with cruel torments." The Pirates were no more than thirty in number, who, notwithstanding, seeing their brave Commander oppose himself with courage to the enemy, resolved to do the like. Hereupon they faced the troop of Spaniards, and discharged their muskets against them with such dexterity, that they killed one horseman with almost every shot. The fight continued for the space of an hour, till at last the Spaniards were put to flight by the Pirates. They stripped the dead, and took from them what they thought most convenient for their use. But such as were not already dead, they helped to quit the miseries of life with the ends of their muskets. Having vanquished the enemy, they all mounted on several horses they found in the field, and continued the journey aforementioned, Brasiliano having lost but two of his companions in this bloody fight, and had two others wounded. As they prosecuted their way, before they came to the port, they espied a boat from Campeche, well manned, that rode at anchor, protecting a small number of canoes that were lading wood. Hereupon they sent a detachment of six of their men to watch them; and these the next morning possessed themselves of the canoes. Having given notice to their companions, they went all on board, and with no great difficulty took also the boat, or little man-of-war, their convoy. Thus having rendered themselves masters of the whole fleet, they wanted only provisions, which they found but very small aboard those vessels. But this defect was supplied by the horses, which they instantly killed and salted with salt which by good fortune the wood-cutters had brought with them. Upon which victuals they made shift to keep themselves, until such time as they could procure better. These very same Pirates, I mean Brasiliano and his companions, took also another ship that was going from New Spain to Maracaibo, laden with divers sorts of merchandise, and a very considerable number of pieces of eight, which were designed to buy cacao-nuts for their lading home. All these prizes they carried into Jamaica. where they safely arrived, and, according to their custom, wasted in a few days in taverns all they had gained, by giving themselves to all manner of debauchery. Such of these Pirates are found who will spend two or three thousand pieces of eight in one night, not leaving themselves peradventure a good shirt to wear on their backs in the morning. My own master would buy, on like occasions, a whole pipe of wine, and, placing it in the street, would force every one that passed by to drink with him; threatening also to pistol them, in case they would not do it. At other times he would do the same with barrels of ale or beer. And, very often, with both his hands, he would throw these liquors about the streets, and wet the clothes of such as walked by, without regarding whether he spoiled their apparel or not, were they men or women. Among themselves, and to each other, these Pirates are extremely liberal and free. If any one of them has lost all his goods, which often happens in their manner of life, they freely give him, and make him partaker of what they have. In taverns and ale-houses they always have great credit; but in such houses at Jamaica they ought not to run very deep in debt, seeing the inhabitants of that island easily sell one another for debt. Thus it happened to my patron, or master, to be sold for a debt of a tavern, wherein he had spent the greatest part of his money. This man had, within the space of three months before, three thousand pieces of eight in ready cash, all which he wasted in that short space of time, and became as poor as I have told you. But now to return to our discourse, I must let my reader know that Brasiliano, after having spent all that he had robbed, was constrained to go to sea again, to seek his fortune once more. Thus he set forth towards the coast of Campeche, his common place of rendezvous. Fifteen days after his arrival there, he put himself into a canoe, with intent to espy the port of that city, and see if he could rob any Spanish vessel. But his fortune was so bad, that both he and all his men were taken prisoners, and carried into the presence of the Governor. This man immediately cast them into a dungeon, with full intention to hang them every person. And doubtless he had performed his intent, were it not for a stratagem that Brasiliano used, which proved sufficient to save their lives. He wrote therefore a letter to the Governor, making him believe it came from other Pirates that were abroad at sea, and withal telling him: He should have a care how he used those persons he had in his custody. For in case he caused them any harm, they did swear unto him they would never give quarter to any person of the Spanish nation that should fall into their hands. Because these Pirates had been many times at Campeche, and in many other towns and villages of the West Indies belonging to the Spanish dominions, the Governor began to fear what mischief they might cause by means of their companions abroad, in case he should punish them. Hereupon he released them out of prison, exacting only an oath of them beforehand, that they would leave their exercise of piracy for ever. And withal he sent them as common mariners, or passengers in the galleons to Spain. They got in this voyage altogether five hundred pieces of eight, whereby they tarried not long there after their arrival. But providing themselves with some few necessaries, they all returned to Jamaica within a little while. Whence they set forth again to sea, committing greater robberies and cruelties than ever they had done before; but more especially abusing the poor Spaniards that happened to fall into their hands, with all sorts of cruelty imaginable. The Spaniards perceiving they could gain nothing upon this sort of people, nor diminish their number, which rather increased daily, resolved to diminish the number of their ships wherein they exercised trading to and fro. But neither was this resolution of any effect, or did them any good service. For the Pirates, finding not so many ships at sea as before, began to gather into greater companies, and land upon the Spanish dominions, ruining whole cities, towns and villages; and withal pillaging, burning and carrying away as much as they could find possible. The first Pirate who gave a beginning to these invasions by land, was named Lewis Scot, who sacked and pillaged the city of Campeche. He almost ruined the town, robbing and destroying all he could; and, after he had put it to the ransom of an excessive sum of money, he left it. After Scot came another named Mansvelt, who enterprized to set footing in Granada, and penetrate with his piracies even to the South Sea. Both which things he effected, till at last, for want of provision, he was constrained to go back. He assaulted the Isle of Saint Catharine, which was the first land he took, and upon it some few prisoners. These showed him the way towards Cartagena, which is a principal city situate in the kingdom of New Granada. But the bold attempts and actions of John Davis, born at Jamaica, ought not to be forgotten in this history, as being some of the most remarkable thereof, especially his rare prudence and valour, wherewith he behaved himself in the aforementioned kingdom of Granada. This Pirate having cruized a long time in the Gulf of Pocatauro upon the ships that were expected from Cartagena bound for Nicaragua, and not being able to meet any of the said ships, resolved at last to land in Nicaragua, leaving his ship concealed about the coast. This design he presently put in execution. For taking fourscore men, out of fourscore and ten which he had in all (the rest being left to keep the ship), he divided them equally into three canoes. His intent was to rob the churches, and rifle the houses of the chief citizens of the aforesaid town of Nicaragua. Thus, in the obscurity of the night, they mounted the river which leads to that city, rowing with oars in their canoes. By day they concealed themselves and boats under the branches of trees that were upon the banks. These grow very thick and intricate along the sides of the rivers in those coun tries, as also along the sea-coast. Under which, likewise, those who remained behind absconded from their vessel, lest they should be seen either by fishermen or Indians. After this manner they arrived at the city the third night, where the sentry, who kept the post of the river, thought them to be fishermen that had been fishing in the lake. And as the greatest part of the Pirates are skilful in the Spanish tongue, so he never doubted thereof as soon as he heard them speak. They had in their company an Indian, who had run away from his master because he would make him a slave after having served him a long time. This Indian went first on shore, and, rushing at the sentry, he instantly killed him. Being animated with this success, they entered into the city, and went directly to three or four houses of the chief citizens, where they knocked with dissimulation. These believing them to be friends opened the doors, and the Pirates suddenly possessing themselves of the houses, robbed all the money and plate they could find. Neither did they spare the churches and most sacred things, all which were pillaged and profaned without any respect or veneration. In the meanwhile great cries and lamentation were heard about the town, of some who had escaped their hands; by which means the whole city was brought into an uproar and alarm. Hence the whole number of citizens rallied together, intending to put themselves in defence. This being perceived by the Pirates, they instantly put themselves to flight, carrying with them all that they had robbed, and likewise some prisoners. These they led away, to the intent that, if any of them should happen to be taken by the Spaniards, they might make use of them for ransom. Thus they got to their ship, and with all speed imaginable put out to sea, forcing the prisoners, before they would let them go, to procure them as much flesh as they thought necessary for their voyage to Jamaica. But no sooner had they weighed anchor, than they saw on shore a troop of about five hundred Spaniards, all being very well armed, at the sea-side. Against these they let fly several guns, wherewith they forced them to quit the sands and retire towards home, with no small regret to see those Pirates carry away so much plate of their churches and houses, though distant at least forty leagues from the rea. These Pirates robbed on this occasion above four thousand pieces of eight in ready money, besides great quantities of plate uncoined and many jewels. All which was computed to be worth the sum of fifty thousand pieces of eight, or more. With this great booty they arrived at Jamaica, soon after the exploit. But as this sort of people are never masters of their money but a very little while, so were they soon constrained to seek more, by the same means they had used before. This adventure caused Captain John Davis, presently after his return, to be chosen Admiral of seven or eight boats of Pirates; he being now esteemed by common consent an able conductor for such enterprizes as these were. He began the exercise of this new command by directing his fleet towards the coasts of the North of Cuba, there to wait for the fleet which was to pass from New Spain. But, not being able to find anything by this design, they determined to go towards the coasts of Florida. Being arrived there, they landed part of their men, and sacked a small city, named Saint Augustine of Florida, the castle of which place had a garrison of two hundred men, which, notwithstanding, could not prevent the pillage of the city, they effecting it without receiving the least damage from either soldiers or townsmen. Hitherto we have spoken in the first part of this book of the constitution of the Islands of Hispaniola and Tortuga, their peculiarities and inhabitants, as also of the fruits to be found in those countries. In the second part of this work we shall bend our discourse to describe the actions of two of the most famous Pirates, who committed many horrible crimes and inhuman cruelties against the Spanish nation.

_____________ 1 A piece of eight is equivalent to about five shillings. |