LX

THE SORCERER

OF THE WHITE LOTUS LODGE

ONCE

upon

a time there was a sorcerer who belonged to the White Lotus Lodge. He

knew how

to deceive the multitude with his black arts, and many who wished to

learn the

secret of his enchantments became his pupils.

One day

the sorcerer wished to go out. He placed a bowl which he covered with

another

bowl in the hall of his house, and ordered his pupils to watch it. But

he

warned them against uncovering the bowl to see what might be in it.

No sooner

had he gone than the pupils uncovered the bowl and saw that it was

filled with

clear water. And floating on the water was a little ship made of straw,

with

real masts and sails. They were surprised and pushed it with their

fingers till

it upset. Then they quickly righted it again and once more covered the

bowl. By

that time the sorcerer was already standing among them. He was angry

and

scolded them, saying: "Why did you disobey my command?"

His pupils

rose and denied that they had done so.

But the

sorcerer answered: "Did not my ship turn turtle at sea, and yet you try

to

deceive me?"

On another

evening he lit a giant candle in his room, and ordered his pupils to

watch it

lest it be blown out by the wind. It must have been at the second watch

of the

night and the sorcerer had not yet come back.

The pupils

grew tired and sleepy, so they went to bed and gradually fell asleep.

When they

woke up again the candle had gone out. So they rose quickly and re-lit

it. But

the sorcerer was already in the room, and again he scolded them.

"Truly

we did not sleep! How could the light have gone out?"

Angrily

the sorcerer replied: "You let me walk fifteen miles in the dark, and

still you can talk such nonsense!"

Then his

pupils were very much frightened.

In the

course of time one of his pupils insulted the sorcerer. The latter made

note of

the insult, but said nothing. Soon after he told the pupil to feed the

swine,

and no sooner had he entered the sty than his Master turned him into a

pig. The

sorcerer then at once called in a butcher, sold the pig to the man, and

he went

the way of all pigs who go to the butcher.

One day

this pupil's father turned up to ask after his son, for he had not come

back to

his home for a long time. The sorcerer told him that his son had left

him long

ago. The father returned home and inquired everywhere for his son

without

success. But one of his son's fellow-pupils, who knew of the matter,

informed

the father. So the father complained to the district mandarin. The

latter,

however, feared that the sorcerer might make himself invisible. He did

not dare

to have him arrested, but informed his superior and begged for a

thousand

well-armed soldiers. These surrounded the sorcerer's home and seized

him,

together with his wife and child. All three were put into wooden cages

to be

transported to the capital.

The road

wound through the mountains, and in the midst of the hills up came a

giant as

large as a tree, with eyes like saucers, a mouth like a plate, and

teeth a foot

long. The soldiers stood there trembling and did not dare to move.

Said the

sorcerer: "That is a mountain spirit. My wife will be able to drive him

off."

They did

as he suggested, unchained the woman, and she took a spear and went to

meet the

giant. The latter was angered, and he swallowed her, tooth and nail.

This

frightened the rest all the more.

The sorcerer

said: "Well, if he has done away with my wife, then it is my son's

turn!"

So they

let the son out of his cage. But the giant swallowed him in the same

way. The

rest all looked on without knowing what to do.

The

sorcerer then wept with rage and said: "First he destroys my wife, and

then my son. If only he might be punished for it! But I am the only one

who can

punish him!"

And, sure

enough, they took him out of his cage, too, gave him a sword, and sent

him out

against the giant. The sorcerer and the giant fought with each other

for a

time, and at last the giant seized the sorcerer, thrust him into his

maw,

stretched his neck and swallowed him. Then he went his way contentedly.

And now

when it was too late, the soldiers realized that the sorcerer had

tricked them.

Note: The

Lodge of the White Lotus is one of the

secret revolutionary societies of China. It harks back to Tung Tian

Gifu Dschu

as its founder. Compare note to No. 18. The "mountain spirit," of

course, is an optical illusion called up by the sorcerer, by means of

which he

frees his family and himself from the soldiers.

LXI

THE THREE

EVILS

ONCE

upon

a time, in the old days, there lived a young man by the name of Dschou

Tschu.

He was of more than ordinary strength, and no one could withstand him.

He was

also wild and undisciplined, and wherever he was, quarrels and brawls

arose.

Yet the village elders never ventured to punish him seriously. He wore

a high

hat on his head, adorned with two pheasants' wings. His garments were

woven of

embroidered silk, and at his side hung the Dragonspring sword. He was

given to

play and to drinking, and his hand was inclined to take that which

belonged to

others. Whoever offended him had reason to dread the consequences, and

he

always mixed into disputes in which others were engaged. Thus he kept

it up for

years, and was a pest throughout the neighborhood.

Then a new

mandarin came to that district. When he had arrived, he first went

quietly

about the country and listened to the people's complaints. And they

told him

that there were three great evils in that district.

Then he

clothed himself in coarse garments, and wept before Dschou Tschu's

door. Dschou

Tschu was just coming from the tavern, where he had been drinking. He

was

slapping his sword and singing in a loud voice.

When he

reached his house he asked: "Who is weeping here so pitifully?"

And the

mandarin replied: "I am weeping because of the people's distress."

Then

Dschou Tschu saw him and broke out into loud laughter.

"You

are mistaken, my friend," said he. "Revolt is seething round about us

like boiling water in a kettle. But here, in our little corner of the

land, all

is quiet and peaceful. The harvest has been abundant, corn is

plentiful, and

all go happily about their work. When you talk to me about distress I

have to

think of the man who groans without being sick. And who are you, tell

me that,

who instead of grieving for yourself, are grieving for others? And what

are you

doing before my door?"

"I am

the new mandarin," replied the other. "Since I left my litter I have

been looking about in the neighborhood. I find the people are honest

and simple

in their way of life, and every one has sufficient to wear and to eat.

This is

all just as you state. Yet, strange to say, when the elders come

together, they

always sigh and complain. And if they are asked why, they answer:

'There are

three great evils in our district!' I have come to ask you to do away

with two

of them, as to the third, perhaps I had better remain silent. And this

is the

reason I weep before your door."

"Well,

what are these evils?" answered Dschou Tschu. "Speak freely, and tell

me openly all that you know!"

"The

first evil," said the mandarin, "is the evil dragon at the long

bridge, who causes the water to rise so that man and beast are drowned

in the

river. The second evil is the tiger with the white forehead, who dwells

in the

hills. And the third evil, Dschou Tschu — is yourself!"

Then the

blush of shame mounted to the man's cheek, and he bowed and said: "You

have come here from afar to be the mandarin of this district, and yet

you feel

such sympathy for the people? I was born in this place and yet I have

only made

our elders grieve. What sort of a creature must I be? I beg that you

will

return home again. I will see to it that matters improve!"

Then he

ran without stopping to the hills, and hunted the tiger out of his

cave. The

latter leaped into the air so that the whole forest was shaken as

though by a

storm. Then he came rushing up, roaring, and stretching out his claws

savagely

to seize his enemy. Dschou Tschu stepped back a pace, and the tiger lit

on the

ground directly in front of him. Then he thrust the tiger's neck to the

ground

with his left hand, and beat him without stopping with his right, until

he lay

dead on the earth. Dschou Tschu loaded the tiger on his back and went

home.

Then he

went to the long bridge. He undressed, took his sword in his hand, and

thus

dived into the water. No sooner had he disappeared, than there was a

boiling

and hissing, and the waves began to foam and billow. It sounded like

the mad

beating of thousands of hoofs. After a time a stream of blood shot up

from the

depths, and the water of the river turned red. Then Dschou Tschu,

holding the

dragon in his hand, rose out of the waves.

He went to

the mandarin and reported, with a bow: "I have cut off the dragon's

head,

and have also done away with the tiger. Thus I have happily

accomplished your

command. And now I shall wander away so that you may be rid of the

third evil

as well. Lord, watch over my country, and tell the elders that they

need sorrow

no more!"

When he

had said this he enlisted as a soldier. In combat against the robbers

he gained

a great reputation and once, when the latter were pressing him hard,

and he saw

that he could not save himself, he bowed to the East and said: "The day

has come at last when I can atone for my sin with my life!" Then he

offered his neck to the sword and died.

Note: A

legendary tale rather than a folk-story, with

a fine moral.

LXII

HOW THREE

HEROES CAME BY THEIR DEATHS BECAUSE OF TWO PEACHES

AT the

beginning of his reign Duke Ging of Tsi loved to draw heroes about him.

Among

those whom he attached to him were three of quite extraordinary

bravery. The

first was named Gung Sun Dsia, the second Tian Kai Gang, the third Gu I

Dsi.

All three were highly honored by the prince, but the honor paid them

made them

presumptuous, they kept the court in a turmoil, and overstepped the

bounds of

respect which lie between a prince and his servants.

At the

time Yan Dsi was chancellor of Tsi. The duke consulted him as to what

would be

best to do. And the chancellor advised him to give a great court

banquet and

invite all his courtiers. On the table, the choicest dish of all, stood

a

platter holding four magnificent peaches.

Then, in

accordance with his chancellor's advice, the Duke rose and said: "Here

are

some magnificent peaches, but I cannot give one to each of you. Only

those most

worthy may eat of them. I myself reign over the land, and am the first

among

the princes of the empire. I have been successful in holding my

possessions and

power, and that is my merit. Hence one of the peaches falls to me. Yan

Dsi sits

here as my chancellor. He regulates communications with foreign lands

and keeps

the peace among the people. He has made my kingdom powerful among the

kingdoms

of the earth. That is his merit, and hence the second peach falls to

him. Now

there are but two peaches left; yet I cannot tell which ones among you

are the

worthiest. You may rise yourselves and tell us of your merits. But

whoever has

performed no great deeds, let him hold his tongue!"

Then Gung Sun Dsia beat upon

his sword, rose up and said: "I

am the prince's captain general. In the South I besieged the kingdom of

Lu, in

the West I conquered the kingdom of Dsin, in the North I captured the

army of

Yan. All the princes of the East come to the Duke's court and

acknowledge the

over-lordship of Tsi. That is my merit. I do not know whether it

deserves a

peach."

The Duke

replied: "Great is your merit! A peach is your just due!"

Then Tian

Kai Giang rose, beat on the table, and cried: "I have fought a hundred

battles in the army of the prince. I have slain the enemy's general-in-chief, and captured the

enemy's flag. I have extended the

borders of the Duke's land till the size of his realm has been

increased by a

thousand miles. How is it with my merit?"

The Duke

said: "Great is your merit! A peach is your just due!"

Then Gu I

Dsi arose; his eyes started from their sockets, and he shouted with a

loud

voice: "Once, when the Duke was crossing the Yellow River, wind and

waters

rose. A river-dragon snapped up one of the steeds of the chariot and

tore it

away. The ferryboat rocked like a sieve and was about to capsize. Then

I took

my sword and leaped into the stream. I fought with the dragon in the

midst of

the foaming waves. And by reason of my strength I managed to kill him,

though

my eyes stood out of my head with my exertions. Then I came to the

surface with

the dragon's head in one hand, and holding the rein of the rescued

horse in the

other, and I had saved my prince from drowning. Whenever our country

was at war

with neighboring states, I refused no service. I commanded the van, I

fought in

single combat. Never did I turn my back on the foe. Once the prince's

chariot

stuck fast in the swamp, and the enemy hurried up on all sides. I

pulled the

chariot out, and drove off the hostile mercenaries. Since I have been

in the

prince's service I have saved his life more than once. I grant that my

merit is

not to be compared with that of the prince and that of the chancellor,

yet it

is greater than that of my two companions. Both have received peaches,

while I

must do without. This means that real merit is not rewarded, and that

the Duke

looks on me with disfavor. And in such case how may I ever show myself

at court

again!"

With these

words he drew his sword and killed himself.

Then thing

Sun Dsia rose, bowed twice, and said with a sigh: "Both my merit and

that

of Tian Kai Giang does not compare with Gu I Dsi's and yet the peaches

were

given us. We have been rewarded beyond our deserts, and such reward is

shameful. Hence it is better to die than to live dishonored!"

He took

his sword and swung it, and his own head rolled on the sand.

Tian Kai

Giang looked up and uttered a groan of disgust. He blew the breath from

his

mouth in front of him like a rainbow, and his hair rose on end with

rage. Then

he took sword in hand and said: "We three have always served our prince

bravely. We were like the same flesh and blood. The others are dead,

and it is

my duty not to survive them!"

And he

thrust his sword into his throat and died.

The Duke

sighed incessantly, and commanded that they be given a splendid burial.

A brave

hero values his honor more than his life. The chancellor knew this, and

that

was why he purposely arranged to incite the three heroes to kill

themselves by

means of the two peaches.

Note: Duke

Ging of Tsi (Eastern Shantung) was an

older contemporary of Confucius. The chancellor Yan Dsi, who is the

reputed

author of a work on philosophy, is the same who prevented the

appointment of

Confucius at the court of Tsi.

LXIII

HOW THE

RIVER-GOD'S WEDDING WAS BROKEN OFF

AT the

time of the seven empires there lived a man by the name of Si-Men Bau,

who was

a governor on the Yellow River. In this district the river-god was held

in high

honor. The sorcerers and witches who dwelt there said: "Every year the

river-god looks for a bride, who must be selected from among the

people. If she

be not found then wind and rain will not come at the proper seasons,

and there

will be scanty crops and floods!" And then, when a girl came of age in

some wealthy family, the sorcerers would say that she should be

selected.

Whereupon her parents, who wished to protect their daughter, would

bribe them with

large sums of money to look for some one else, till the sorcerers would

give

in, and order the rich folk to share the expense of buying some poor

girl to be

cast into the river. The remainder of the money they would keep for

themselves

as their profit on the transaction. But whoever would not pay, their

daughter

was chosen to be the bride of the river-god, and was forced to accept

the

wedding gifts which the sorcerers brought her. The people of the

district

chafed grievously under this custom.

Now when

Si-Men entered into office, he heard of this evil custom. He had the

sorcerers

come before him and said: "See to it that you let me know when the day

of

the river-god's wedding comes, for I myself wish to be present to honor

the

god! This will please him, and in return he will shower blessings on my

people." With that he dismissed them. And the sorcerers were full of

praise for his piety.

So when

the day arrived they gave him notice. Si-Men dressed himself in his

robes of

ceremony, entered his chariot and drove to the river in festival

procession.

The elders of the people, as well as the sorcerers and the witches were

all

there. And from far and near men, women and children had flocked

together in

order to see the show. The sorcerers placed the river-bride on a couch,

adorned

her with her bridal jewels, and kettledrums, snaredrums and merry airs

vied

with each other in joyful sound.

They were

about to thrust the couch into the stream, and the girl's parents said

farewell

to her amid tears. But Si-Men bade them wait and said: "Do not be in

such

a hurry! I have appeared in person to escort the bride, hence

everything must

be done solemnly and in order. First some one must go to the

river-god's

castle, and let him know that he may come himself and fetch his bride."

And with

these words he looked at a witch and said: "You may go!" the witch

hesitated, but he ordered his servants to seize her and thrust her into

the

stream. After which about an hour went by.

"That

woman did not understand her business," continued Si-Men, "or else

she would have been back long ago!" And with that he looked at one of

the

sorcerers and added: "Do you go and do better!" The sorcerer paled

with fear, but Si-Men had him seized and cast into the river. Again

half-an-hour

went by.

Then

Si-Men pretended to be uneasy. "Both of them have made a botch of their

errand," said he, "and are causing the bride to wait in vain!"

Once more he looked at a sorcerer and said: "Do you go and hunt them

up!”

But the sorcerer flung himself on the ground and begged for mercy. And

all the

rest of the sorcerers and witches knelt to him in a row, and pleaded

for grace.

And they took an oath that they would never again seek a bride for the

river-god.

Then

Si-Men held his hand, and sent the girl back to her home, and the evil

custom

was at an end forever.

Note:

Si-Men Bau was an historical personage, who

lived five centuries before Christ.

LXIV

DSCHANG

LIANG

DSCHANG

LIANG was a native of one of those states which had been destroyed by

the

Emperor Tsin Schi Huang. And Dschang Liang determined to do a deed for

his dead

king's sake, and to that end gathered followers with whom to slay Tsin

Schi

Huang.

Once Tsin

Schi Huang was making a progress through the country. When he came to

the plain

of Bo Lang, Dschang Liang armed his people with iron maces in order to

kill

him. But Tsin Schi Huang always had two traveling coaches which were

exactly

alike in appearance. In one of them he sat himself, while in the other

was

seated another person. Dschang Liang and his followers met the decoy

wagon, and

Dschang Liang was forced to flee from the Emperor's rage. He came to a

ruined

bridge. An icy wind was blowing, and the snowflakes were whirling

through the

air. There he met an old, old man wearing a black turban and a yellow

gown. The

old man let one of his shoes fall into the water, looked at Dschang

Liang and

said: "Fetch it out, little one!"

Dschang

Liang controlled himself, fetched out the shoe and brought it to the

old man.

The latter stretched out his foot to allow Dschang Liang to put it on,

which he

did in a respectful manner. This pleased the old man and he said:

"Little

one, something may be made of you! Come here to-morrow morning early,

and I

will have something for you."

The

following morning at break of dawn, Dschang Liang appeared. But the old

man was

already there and reproached him: "You are too late. To-day I will tell

you nothing. To-morrow you must come earlier."

So it went

on for three days, and Dschang Liang's patience was not exhausted. Then

the old

man was satisfied, brought forth the Book of Hidden Complements, and

gave it to

him. "You must read it," said he, "and then you will be able to

rule a great emperor. When your task is completed, seek me at the foot

of the

Gu Tschong Mountain. There you will find a yellow stone, and I will be

by that

yellow stone."

Dschang

Liang took the book and aided the ancestor of the Han dynasty to

conquer the

empire. The emperor made him a count. From that time forward Dschang

Liang ate

no human food and concentrated in spirit. He kept company with the four

whitebeards of the Shang Mountain, and with them shared the sunset poses in the clouds. Once

he met two boys who were singing

and dancing:

"Geen the garments you

should wear,

If to heaven's gate you'd

fare;

There the Golden Mother

greet,

Bow before the Wood

Lord's feet!"

When

Dschang Liang heard this, he bowed before the youths, and said to his

friends:

"Those are angel children of the King Father of the East. The Golden

Mother is the Queen of the West. The Lord of Wood is the King Father of

the

East. They are the two primal powers, the parents of all that is male

and

female, the root and fountain of heaven and earth, to whom all that has

life is

indebted for its creation and nourishment. The Lord of Wood is the

master of

all the male saints, the Golden Mother is the mistress of all the

female

saints. Whoever would gain immortality, must first greet the Golden

Mother and

then bow before the King Father. Then he may rise up to the three Pure

Ones and

stand in the presence of the Highest. The song of the angel children

shows the

manner in which the hidden knowledge may be acquired."

At about

that time the emperor was induced to have some of his faithful servants

slain.

Then Dschang Liang left his service and went to the Gu Tschong

Mountain. There

he found the old man by the yellow stone, gained the hidden knowledge,

returned

home, and feigning illness loosed his soul from his body and

disappeared.

Later,

when the rebellion of the "Red Eyebrows" broke out, his tomb was

opened. But all that was found within it was a yellow stone. Dschang

Liang was

wandering with Laotsze in the invisible world.

Once his

grandson Dschang Dan Ling went to Kunlun Mountain, in order to visit

the Queen

Mother of the West. There he met Dschang Liang. Dschang Dau Ling gained

power

over demons and spirits, and became the first Taoist pope. And the

secret of

his power has been handed down in his family from generation to

generation.

Note: "In

a yellow robe," is an indication

of Taoism: compare with No. 38. "The Book of Hidden Complements" (Yin

Fu Ging). Compare with Lia Dsi, Introduction.

LXV

OLD

DRAGONBEARD

AT the

time of the last emperor of the Sui dynasty, the power was in the hands

of the

emperor's uncle, Yang Su. He was proud and extravagant.

In his halls stood choruses of singers and bands of dancing girls, and

serving-maids stood ready to obey his least sign. When the great lords

of the

empire came to visit him he remained comfortably seated on his couch

while he

received them.

In those

days there lived a bold hero named Li Dsing. He came to see Yang Su in

humble

clothes in order to bring him a plan for the quieting of the empire.

He made a

low bow to which Yang Su did not reply, and then he said: "The empire

is

about to be troubled by dissension and heroes are everywhere taking up

arms.

You are the highest servant of the imperial house. It should be your

duty to

gather the bravest around the throne. And you should not rebuff people

by your

haughtiness!"

When Yang

Su heard him speak in this fashion he collected himself, rose from his

place,

and spoke to him in a friendly manner.

Li Dsing

handed him a memorial, and Yang Su entered into talk with him

concerning all

sorts of things. A serving-maid of extraordinary beauty stood beside

them. She

held a red flabrum in her hand, and kept her eyes fixed on Li Dsing.

The latter

at length took his leave and returned to his inn.

Later in

the day some one knocked at his door. He looked out, and there, before

the

door, stood a person turbaned and gowned in purple, and carrying a bag

slung

from a stick across his shoulder.

Li Dsing

asked who it was and received the answer: "I am the fan-bearer of Yang

Su!"

With that

she entered the room, threw back her mantle and took off her turban. Li

Dsing

saw that she was a maiden of eighteen or nineteen.

She bowed

to him, and when he had replied to her greeting she began: "I have

dwelt

in the house of Yang Su far a long time and have seen many famous

people, but

none who could equal you. I will serve you wherever you go!"

Li Dsing

answered: "The minister is powerful. I am afraid that we will plunge

ourselves into misfortune."

"He

is a living corpse, in whom the breath of life grows scant," said the

fan-bearer, "and we need not fear him."

He asked

her name, and she said it was Dschang, and that she was the oldest

among her

brothers and sisters.

And when

he looked at her, and considered her courageous behavior and her

sensible

words, he realized that she was a girl of heroic cast, and they agreed

to marry

and make their escape from the city in secret. The fan-bearer put on

men's

clothes, and they mounted horses and rode away. They had determined to

go to

Taiyuanfn.

On the

following day they stopped at an inn. They had their room put in order

and made

a fire on the hearth to cook their meal. The fan-bearer was combing her

hair.

It was so long that it swept the ground, and so shining that you could

see your

face in it. Li Dsing had just left the room to groom the horses.

Suddenly a man

who had a long curling mustache like a dragon made his appearance. He

came

along riding on a lame mule, threw down his leather bag on the ground

in front

of the hearth, took a pillow, made himself comfortable on a conch, and

watched

the fan-bearer as she combed her hair. Li Dsing saw him and grew angry;

but the

fan-bearer had at once seen through the stranger. She motioned Li Dsing

to

control himself, quickly finished combing her hair and tied it in a

knot.

Then she

greeted the guest and asked his name. He told her that he was named

Dschang.

"Why,

my name is also Dschang," said she, "so we must be relatives!"

Thereupon

she bowed to him as her elder brother. "How many are there of you

brothers?" she then inquired.

"I am

the third," he answered, "and you?"

"I am

the oldest sister."

"How

fortunate that I should have found a sister to-day," said the stranger,

highly pleased.

Then the

fan-bearer called to Li Dsing through the door and said: "Come in! I

wish

to present my third brother to you!"

Then Li

Dsing came in and greeted him.

They sat

down beside each other and the stranger asked: "What have you to

eat?"

"A

leg of mutton," was the answer.

"I am

quite hungry," said the stranger.

So Li

Dsing went to the market and brought bread and wine. The stranger drew

out his

dagger, cut the meat, and they all ate in company. When they had

finished he

fed the rest of the meat to his mule.

Then he

said: "Sir Li, you seem to be a money-less knight. How did you happen

to

meet my sister?"

Li Dsing

told him how it had occurred.

"And

where do you wish to go now?"

"To

Taiyuanfu," was the answer.

Said the

stranger: "You do not seem to be an ordinary fellow. Have you heard

anything regarding a hero who is supposed to be in this neighborhood?"

Li Dsing

answered: "Yes, indeed, I know of one, whom heaven seems destined to

rule."

"And

who might he be?" inquired the other.

"He

is the son of Duke Li Yuan of Tang, and he is no more than twenty years

of

age."

"Could

you present him to me some time?" asked the stranger.

And when

Li Dsing has assured him he could, he continued: "The astrologers say

that

a special sign has been noticed in the air above Taiyuanfu. Perhaps it

is

caused by the very man. To-morrow you may await me at the Fenyang

Bridge!"

With these

words he mounted his mule and rode away, and he rode so swiftly that he

seemed

to be flying.

The

fan-bearer said to him: "He is not a pleasant customer to deal with. I

noticed that at first he had no good intentions. That is why I united

him to us

by bonds of relationship."

Then they

set out together for Taiyuanfu, and at the appointed place, sure

enough, they

met Dragon-beard. Li Dsing had an old friend, a companion of the Prince

of

Tang.

He

presented the stranger to this friend, named Liu Wendsing, saying:

"This

stranger is able to foretell the future from the lines of the face, and

would

like to see the prince."

Thereupon

Liu Wendsing took him in to the prince. The prince was clothed in a

simple

indoor robe, but there was something impressive about him, which made

him

remarked among all others. When the stranger saw him, he fell into a

profound

silence, and his face turned gray. After he had drunk a few flagons of

wine he

took his leave.

"That

man is a true ruler," he told Li Dsing. "I am almost certain of the

fact, but to be sure my friend must also see him."

Then he

arranged to meet Li Dsing on a certain day at a certain inn.

"When

you see this mule before the door, together with a very lean jackass,

then you

may be certain I am there with my friend."

On the day

set Li Dsing went there and, sure enough he saw the mule and the

jackass before

the door. He gathered up his robe and descended to the upper story of

the inn.

There sat old Dragonbeard and a Taoist priest over their wine. When the

former

saw Li Dsing he was much pleased, bade him sit down and offered him

wine. After

they had pledged each other, all three returned to Lui Wendsing. He was

engaged

in a game of chess with the prince. The prince rose with respect and

asked them

to be seated.

As soon as

the Taoist priest saw his radiant and heroic countenance he was

disconcerted,

and greeted him with a low bow, saying: "The game is up "

When they

took their leave Dragonbeard said to Li Dsing: "Go on to Sianfu, and

when

the time has come, ask for me at such

and such a

place."

And with

that he went away snorting.

Li Dsing

and the fan-bearer packed up their belongings, left Taiyuanfu and

traveled on

toward the West. At that time Yang Su died, and great disturbance arose

throughout the empire.

In the

course of a few days Li Dsing and his wife reached the meeting-place

appointed

by Dragonbeard. They knocked at a little wooden door, and out came a

servant,

who led them through long passages. When they emerged magnificent

buildings

arose before them, in front of which stood a crowd of slave girls. Then

they

entered a hall in which the most valuable dowry that could be imagined

had been

piled up: mirrors, clothes, jewelry, all more beautiful than earth is

wont to

show. Handsome slave girls led them to the bath, and when they had

changed their

garments their friend was announced. He stepped in clad in silks and

fox-pelts,

and looking almost like a dragon or a tiger. He greeted his guests with

pleasure and also called in his wife, who was of exceptional

loveliness. A

festive banquet was served, and all four sat down to it. The table was

covered

with the most expensive viands, so rare that they did not even know

their

names. Flagons and dishes and all the utensils were made of gold and

jade, and

ornamented with pearls and precious stones.

Two companies

of girl musicians alternately blew flutes and chalameaus. They sang and

danced,

and it seemed to the visitors that they had been transported to the

palace of

the Lady of the Moon. The rainbow garments fluttered, and the dancing

girls

were beautiful beyond all the beauty of earth.

After they

had banqueted, Dragonbeard commanded his servitors to bring in couches

upon

which embroidered silken covers had been spread. And after they had

seen

everything worth seeing, he presented them with a book and a key.

Then he

said: "In this book are listed the valuables and the riches which I

possess. I make you a wedding-present of them. Nothing great may be

undertaken

without wealth, and it is my duty to endow my sister properly. My

original

intention had been to take the Middle Kingdom in hand and do something

with it.

But since a ruler has already arisen to reign over it, what is there to

keep me

in this country? For Prince Tang of Taiyuanfu is a real hero, and will

have

restored order within a few years' time. You must both of you aid him,

and you

will be certain to rise to high honors. You, my sister, are not alone

beautiful, but you have also the right way of looking at things. None

other

than yourself would have been able to recognize the true worth of Li

Dsing, and

none other than Li Dsing would have had the good fortune to encounter

you. You

will share the honors which will be your husband's portion, and your

name will

be recorded in history. The treasures which I bestow upon you, you are

to use

to help the true ruler. Bear this in mind! And in ten years' time a

glow will

rise far away to the Southeast, and it shall be a sign that I have

reached my

goal. Then you may pour a libation of wine in the direction of the

South-east,

to wish me good fortune!"

Then, one

after another, he had his servitors and slave-girls greeted Li Dsing

and the

fan-bearer, and said to them: "This is your master and your

mistress!"

When he

had spoken these words, he took his wife's hand, they mounted three

steeds

which were held ready, and rode away.

Li Dsing

and his wife now established themselves in the house, and found

themselves

possessed of countless wealth. They followed Prince Tang, who restored

order to

the empire, and aided him with their money. Thus the great work was

accomplished,

and after peace had been restored throughout the empire, Li Dsing was

made Duke

of We, and the fan-bearer became a duchess.

Some ten

years later the duke was informed that in the empire beyond the sea a

thousand

ships had landed an army of a hundred thousand armored soldiers. These

had

conquered the country, killed its prince, and set up their leader as

its king.

And order now reigned in that empire.

Then the

duke knew that Dragonbeard had accomplished his aim. He told his wife,

and they

robed themselves in robes of ceremony and offered wine in order to wish

him

good fortune. And they saw a radiant crimson ray flash up on the

South-eastern

horizon. No doubt Dragonbeard had sent it in answer. And both of them

were very

happy.

Note: Yang

Su died in the year 606 A.D. The Li Dsing

of this tale has nothing in common with Li Dsing, the father of

Notschka (No.

18). He lived as a historical personage, 571-649 A.D. Li Yuan was the

founder

of the Tang dynasty, 565-635 A.D. His famous son, to whom he owed the

throne,

the “Prince of Tang," was named Li Schi Min. His father abdicated in

618

in his favor. This tale is not, of course, historical, but legendary.

Compare

with the introduction of the following one.

LXVI

HOW MOLO STOLE

THE LOVELY ROSE-RED

AT the

time

when the Tang dynasty reigned over the Middle Kingdom, there were

master

swordsmen of various kinds. Those who came first were the saints of the

sword.

They were able to take different shapes at will, and their swords were

like

strokes of lightning. Before their opponents knew they had been struck

their

heads had already fallen. Yet these master swordsmen were men of lofty

mind,

and did not lightly mingle in the quarrels of the world. The second

kind of

master swordsmen were the sword heroes. It was their custom to slay the

unjust,

and to come to the aid of the oppressed. They wore a hidden dagger at

their

side and carried a leather bag at their belt. By magic means they were

able to

turn human heads into flowing water. They could fly over roofs and walk

up and

down walls, and they came and went and left no trace. The swordsmen of

the

lowest sort were the mere bought slayers. They hired themselves out to

those

who wished to do away with their enemies. And death was an everyday

matter to

them.

Old Dragonbeard

must have been a master swordsman standing midway between those of the

first

and of the second order. Molo however,

of whom this story tells, was a sword hero.

At that

time there lived a young man named Tsui, whose father was a high

official and

the friend of the prince. And the father once sent his son to visit his

princely friend, who was ill. The son was young, handsome and gifted.

He went

to carry out his father's instructions. When he entered the prince's

palace,

there stood three beautiful slave girls, who piled rosy peaches into a

golden

bowl, poured sugar over them and presented them to him. After he had

eaten he

took his leave, and his princely host ordered one of the slave girls,

Rose-Red

by name, to escort him to the gate. As they went along the young man

kept

looking back at her. And she smiled at him and made signs with her

fingers.

First she would stretch out three fingers, then she would turn her hand

around

three times, and finally she would point to a little mirror which she

wore on her

breast. When they parted she whispered to him: "Do not forget me!"

When the

young man reached home his thoughts were all in confusion. And he sat

down

absent-mindedly like a wooden rooster. Now it happened that he had an

old

servant named Molo, who was an extraordinary being.

"What

is the trouble, master," said he. "Why are you so sad? Do you not

want to tell your old slave about it?"

So the boy

told him what had occurred, and also mentioned the signs the girl had

made to

him in secret.

Said Molo:

"When she stretched out three fingers, it meant that she is quartered

in

the third court of the palace. When she turned round her hand three

times, it

meant the sum of three times five fingers, which is fifteen. When she

pointed

at the little mirror, she meant to say that on the fifteenth, when the

moon is

round as a mirror, at midnight, you are to go for her."

Then the

young man was roused from his confused thoughts, and was so happy he

could

hardly control himself.

But soon

he grew sad again and said: "The prince's palace is shut off as though

by

an ocean. How would it be possible to win into it?"

"Nothing

easier," said Mok. "On the fifteenth we will take two pieces of dark

silk and wrap ourselves up in them, and thus I will carry you there.

Yet there

is a wild dog on guard at the slave girl's court, who is strong as a

tiger and

watchful as a god. No one can pass by him, so he must be killed."

When the

appointed day had come, the servant said: "There is no one else in the

world who can kill this dog but myself!"

Full of

joy the youth gave him meat and wine, and the old man took a

chain-hammer and

disappeared with it.

And after

no more time had elapsed than it takes to eat a meal he was back again

and

said: "The dog is dead, and there is nothing further to hinder us!"

At

midnight they wrapped themselves in dark silk, and the old man carried

the

youth over the tenfold walls which surrounded the palace. They reached

the

third gateway and the gate stood ajar. Then they saw the glow of a

little lamp,

and heard Rose-Red sigh deeply. The entire court was silent and

deserted. The

youth raised the curtain and stepped into the room. Long and

searchingly

Rose-Red looked at him, then seized his hand.

"I

knew that you were intelligent, and would understand my sign language.

But what

magic power have you at your disposal, that you were able to get here?"

The youth

told her in detail how Molo had

helped him.

"And

where is Molo?" she asked.

"Outside,

before the curtain," was his answer.

Then she

called him in and gave him wine to drink from a jade goblet and said:

"I

am of good family and have come here from far away. Force alone has

made me a

slave in this palace. I long to leave it. For though I have jasper

chop-sticks

with which to eat, and drink my wine from golden flagons, though silk

and satin

rustle around me and jewels of every kind are at my disposal, all these

are but

so many chains and fetters to hold me here. Dear Molo, you are endowed

with

magic powers. I beg you to save me in my distress! If you do, I will be

glad to

serve your master as a slave, and will never forget the favor you do

me."

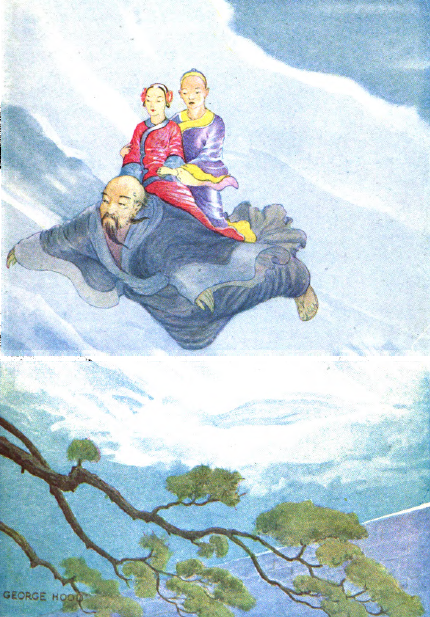

"THEN

HE TOOK HIS MASTER AND ROSE-RED UPON HIS BACK AND FLEW WITH

THEM OVER THE STEEP WALLS."

The

youth

looked at Molo. Molo was quite willing. First he asked permission to

carry away

Rose-Red's gear and jewels in sacks and bags. Three times he went away

and

returned until he had finished. Then he took his master and Rose-Red

upon his

back, and flew away with them over the steep walls. None of the

watchmen of the

prince's palace noticed anything out of the way. At home the youth hid

Rose-Red

in a distant room.

When the

prince discovered that one of his slave-girls was missing, and that one

of his

wild dogs had been killed, he said: "That must have been some powerful

sword

hero!" And he gave strict orders that the matter should not be

mentioned,

and that investigations should be made in secret.

Two years

passed, and the youth no longer thought of any danger. Hence, when the

flowers

began to bloom in the spring, Rose-Red went driving in a small wagon

outside

the city, near the river. And there one of the prince's servants saw

her, and

informed his master. The latter sent for the youth, who, since he could

not

conceal the matter, told him the whole story exactly as it had

happened.

Said the

prince: "The whole blame rests on Rose-Red. I do not reproach you. Yet

since she is now your wife I will let the whole matter rest. But Molo

will have

to suffer for it!"

So he

ordered a hundred armored soldiers, with bows and swords, to surround

the house

of the youth, and under all circumstances to take Molo captive. But Molo drew his dagger and flew

up the high wall. Thence he looked

about him like a hawk. The arrows flew as thick as rain, but not one

hit him.

And in a moment he had disappeared, no one knew where.

Yet ten

years later one of his former master's servants ran across him in the

South,

where he was selling medicine. And he looked exactly as he had looked

ten years

before.

Note: This

fairy-tale has many features in common

with the fairy-tales of India, noticeably the use of the sign language,

which

the hero himself does not understand, but which is understood by his

companion.

LXVII

THE GOLDEN

CANISTER

IN the

days of the Tang dynasty there lived a certain count

in the camp at Ludschou. He had a slave who could play the lute

admirably, and was also so well versed in reading and writing that the

count

employed her to write his confidential

letters.

Once there

was a great feast held in the camp. Said the slave-girl: "The large

kettle-drum sounds so sad to-day; some misfortune must surely have

happened to

the kettle-drummer!"

The count

sent for the kettle-drummer

and questioned him.

"My

wife has died," he replied, "yet I did not venture to ask for leave

of absence. That is why, in spite of me, my kettle-drum sounded so

sad."

The count

allowed him to go home.

At that

time there was much strife and jealousy among the counts along the

Yellow

River. The emperor wished to put an end to their dissensions by allying

them to

each other by marriages. Thus the daughter of the Count of Ludschou had

married

the son of the old Count of Webo. But this did not much improve

matters. The

old Count of Webo had lung trouble, and when the hot season came it

always grew

worse, and he would say: "Yes, if I only had Ludschou! It is cooler and

I

might feel better there!”

So he

gathered three thousand warriors around him, gave them good pay,

questioned the

oracle with regard to a lucky day, and set out to take Ludschou by

force.

The Count

of Ludschou heard of it. He worried day and night, but could see no way

out of

his difficulties. One night, when the water-clock had already been set

up, and

the gate of the camp had been locked, he walked about the courtyard,

leaning on

his staff. Only his slave-girl followed him.

"Lord,"

said she, "it is now more than a month since sleep and appetite have

abandoned you! You live sad and lonely, wrapped up in your grief.

Unless I am

greatly deceived it is on account of Webo."

"It

is a matter of life and death," answered the count, "of which you

women understand nothing."

"I am

no more than a slave-girl," said she, "and yet I have been able to

guess the cause of your grief."

The count

realized that there was meaning in her words and replied: "You are in

truth an extraordinary girl. It is a fact that I am quietly reflecting

on some

way of escape."

The

slave-girl said: "That is easily done. You need

not give it a thought, master. I will go

to Webo and see how things are. This is the first watch of the night.

If I go

now, I can be back by the fifth watch."

"Should

you not succeed," said the count, "you merely bring misfortune upon

me the more quickly."

"A

failure is out of the question," answered the slave-girl.

Then she

went to her room and prepared for her journey. She combed her raven

hair, tied

it in a knot on the top of her head, and fastened it with a golden pin.

Then

she put on a short garment embroidered with purple, and shoes woven of

dark

silk. In her breast she hid a dagger with dragon-lines graved on it,

and upon

her forehead she wrote the name of the Great God. Then she bowed before

the

count and disappeared.

The count

poured wine for himself and waited for her, and when the morning horn

was

blown, the slave-girl floated down before him as light as a leaf.

"Did

all go well?" asked the count.

"I

have done no discredit to my mission," replied the girl.

"Did

you kill any one?"

"No,

I did not have to go to such lengths. Yet I took the golden canister at

the

head of Webo's couch along as a pledge."

The count

asked what her experience had been, and she began to tell her story:

"I

set out when the drums were beating their first tattoo and reached Webo

three

hours before midnight. When I stepped through the gate, I could see the

sentries asleep in their guard-rooms. They snored so that it sounded

like

thunder. The camp sentinels were pacing their beats, and I went in

through the

left entrance into the room in which the Count of Webo slept. There lay

your

relative on his back behind the curtain, plunged in sweet slumber. A

costly

sword showed from beneath his pillow; and beside it stood an open

canister of

gold. In the canister were various slips. On one of them was set down

his age

and the day of his birth, on another the name of the Great Bear God.

Grains of

incense and pearls were scattered over it. The candles in the room

burned

dimly, and the incense in the censers was paling to ash. The

slave-girls lay

huddled up, round about, asleep. I could have drawn out their hair-pins

and

raised their robes and they would not have awakened. Your relative's

life was

in my hand, but I could not bring myself to kill him. So I took the

golden

canister and returned. The water-clock marked the third hour when I had

finished my journey. Now you must have a swift horse saddled quickly,

and must

send a man to Webo to take back the golden canister. Then the Lord of

Webo will

come to his senses, and will give up his plans of conquest."

The Count

of Ludschou at once ordered an officer to ride to Webo as swiftly as

possible. He

rode all day long and half the night and finally arrived. In Webo every

one was

excited because of the loss of the golden canister. They were searchng

the

whole camp rigorously. The messenger knocked at the gate with his

riding-whip,

and insisted on seeing the Lord of Webo. Since he came at so unusual an

hour

the Lord of Webo guessed that he was bringing important information,

and left

his room to receive the messenger. The latter handed him a letter which

said:

"Last night a stranger from Webo came to us. He informed us that with

his

own hands he had taken a golden canister from beside your bed. I have

not

ventured to keep it and hence am sending it back to you by messenger."

When the Lord of Webo saw the golden canister he was much frightened.

He took the

messenger into his own room, treated him to a splendid meal, and

rewarded him

generously.

On the

following day he sent the messenger back again, and gave him thirty

thousand

bales of silk and a team of four horses along as a present for his

master. He also

wrote a letter to the Count of Ludschou:

"My

life was in your hand. I thank you for having spared me, regret my evil

intentions and will improve. From this time forward peace and

friendship shall

ever unite us, and I will let no thought to the contrary enter my mind.

The

citizen soldiery I have gathered I will use only as a protection

against

robbers. I have already disarmed the men and sent them back to their

work in

the fields."

And

thenceforward the heartiest friendship existed between the two

relatives North

and South of the Yellow River.

One day

the slave-girl came and wished to take leave of her master.

"In

my former existence," said the slave-girl, "I was a man. I was a

physician and helped the sick. Once upon

a time I gave a little child a poison to drink by mistake instead of a

healing

draught, and the child died. This led the Lord of Death to punish me,

and I

came to earth again in the shape of a slave-girl. Yet I remembered my

former

life, tried to do well in my new surroundings, and even found a rare

teacher

who taught me the swordsman's art. Already I have served you for

nineteen

years. I went to Webo for you in order to repay your kindness. And I

have

succeeded in shaping matters so that you are living at peace with your

relatives again, and thus have saved the lives of thousands of people.

For a

weak woman this is a real service, sufficient to absolve me of my

original

fault. Now I shall retire from the world and dwell among the silent

hills, in

order to labor for sanctity with a clean heart. Perhaps I may thus

succeed in

returning to my former condition of life. So I beg of you to let me

depart!"

The count

saw that it would not be right to detain her any longer. So he prepared

a great

banquet, invited a number of guests to the farewell meal, and many a

famous

knight sat down to the board. And all honored her with toasts and

poems.

The count

could no longer hide his emotion, and the slave-girl also bowed before

him and

wept. Then she secretly left the banquet-hall, and no human being ever

discovered whither she had gone.

Note: This

motive of the intelligent slave-girl also

occurs in the story of the three empires. "On her forehead she wrote

the

name of the Great God:" Regarding this god, Tai I, the Great One,

compare

annotation to No. 18. The God of the Great Bear, i. e., of the

constellation.

The letters which are exchanged are quite as noticeable for what is

implied

between the lines, as for what is actually set down.

LXVIII

YANG GUI

FE

THE

favorite wife of the emperor Ming Huang of the Tang dynasty was the

celebrated

Yang Gui Fe. She so enchanted him by her beauty that he did whatever

she wished

him to do. But she brought her cousin to the court, a gambler and a

drinker,

and because of him the people began to murmur against the emperor.

Finally a

revolt broke out, and the emperor was obliged to flee. He fled with his

entire

court to the land of the four rivers.

But when

they reached a certain pass his own soldiers mutinied. They shouted

that Yang

Gui Fe's cousin was to blame for all, and that he must die or they

would go no

further. The emperor did not know what to do. At last the cousin was

delivered

up to the soldiers and was slain. But still they were not satisfied.

"As

long as Yang Gui Fe is alive she will do all in her power to punish us

for the

death of her cousin, so she must die as well!"

Sobbing,

she fled to the emperor. He wept bitterly and endeavored to protect

her; but

the soldiers grew more and more violent. Finally she was hung from a

pear-tree

by a eunuch.

The emperor

longed so greatly for Yang Gui Fe that he ceased to eat, and could no

longer

sleep. Then one of his eunuchs told him of a man named Yang Shi Wu, who

was

able to call up the spirits of the departed. The emperor sent for him

and Yang

Shi Wu appeared.

That very

evening he recited his magic incantations, and his soul left its body

to go in

search of Yang Gui Fe. First he went to the Nether World, where the

shades of

the departed dwell. Yet no matter how much he looked and asked he could

find no

trace of her. Then he ascended to the highest heaven, where sun, moon

and stars

make their rounds, and looked for her in empty space. Yet she was not

to be

found there, either. So he came back and told the emperor of his

experience.

The emperor was dissatisfied and said: "Yang Gui Fe's beauty was

divine.

How can it be possible that she had no soul!"

The

magician answered: "Between hill and valley and amid the silent ravines

dwell the blessed. I will go back once more and search for her there."

So he

wandered about on the five holy hills, by the four great rivers and

through the

islands of the sea. He went everywhere, and finally came to fairyland.

The fairy

said: "Yang Gui Fe has become a blessed spirit and dwells in the great

south palace!"

So the

magician went there and knocked on the door. A maiden came out and

asked what

he wanted, and he told her that the emperor had sent him to look for

her

mistress. She let him in. The way led through broad gardens filled with

flowers

of jade and trees of coral, giving forth the sweetest of odors. Finally

they

reached a high tower, and the maiden raised the curtain hanging before

a door.

The magician kneeled and looked up. And there he saw Yang Gui Fe

sitting on a

throne, adorned with an emerald headdress and furs of yellow swans'

down. Her

face glowed with rosy color, yet her forehead was wrinkled with care.

She said:

"Well do I know the emperor longs for me! But for me there is no path

leading back to the world of men! Before my birth I was a blessed

sky-fairy,

and the emperor was a blessed spirit as well. Even then we loved each

other

dearly. Then, when the emperor was sent down to earth by the Lord of

the

Heavens, I, too, descended to earth and found him there among men. In

twelve

years' time we will meet again. Once, on the evening of the seventh

day, when

we stood looking up at the Weaving Maiden and the Herd Boy, we swore

eternal

love. The emperor had a ring, which he broke in two. One half he gave

to me,

the other he kept himself. Take this half of mine, bring it to the

emperor, and

tell him not to forget the words we said to each other in secret that

evening.

And tell him not to grieve too greatly because of me!"

With that

she gave him the ring, with difficulty suppressing her sobs. The

magician

brought back the ring with him. At sight of it the emperor's grief

broke out

anew.

He said:

"What we said to each other that evening no one else has ever learned!

And

now you bring me back her ring! By that sign I know that your words are

true

and that my beloved has really become a blessed spirit."

Then he

kept the ring and rewarded the magician lavishly.

Note: The

emperor Ming Huang of the Tang dynasty

ruled from 713 to 756 A.D. The introduction to the tale is historical.

The

"land of the four rivers" is Setchuan.

LXIX

THE MONK

OF THE YANGTZE-KIANG

BUDDHISM

took its rise in southern India, on the island of Ceylon. It was there

that the

son of a Brahminic king lived, who had left his home in his youth, and

had

renounced all wishes and all sensation. With the greatest renunciation

of self

he did penance so that all living creatures might be saved. In the

course of

time he gained the hidden knowledge and was called Buddha.

In the

days of the Emperor Ming Di, of the dynasty of the Eastern Hans, a

golden glow

was seen in the West, a glow which flashed and shone without

interruption.

One night

the emperor dreamed that he saw a golden saint, twenty feet in height,

barefoot, his head shaven, and clothed in Indian garb enter his room,

who said

to him: "I am the saint from the West! My gospel must be spread in the

East!”

When the

ruler awoke he wondered about this dream, and sent out messengers to

the lands

of the West in order to find out what it meant.

Thus it

was that the gospel of Buddha came to China, and continued to gain in

influence

up to the time of the Tang dynasty. At that time, from emperors and

kings down

to the peasants in the villages, the wise and the ignorant alike were

filled

with reverence for Buddha. But under the last two dynasties his gospel

came to

be more and more neglected. In these days the Buddhist monks run to the

houses

of the rich, read their sutras and pray for pay. And one hears nothing

of the

great saints of the days gone by.

At the

time of the Emperor Tai Dsung, of the Tang dynasty, it once happened

that a

great drought reigned in the land, so that the emperor and all his

officials

erected altars everywhere in order to plead for rain.

Then the

Dragon-King of the Eastern Sea talked with the Dragon of the Milky Way

and

said: "To-day they are praying for rain on earth below. The Lord of the

Heavens has granted the prayer of the King of Tang. To-morrow you must

let

three inches of rain fall!"

"No,

I must let only two inches of rain fall," said the old dragon.

So the two

dragons made a wager, and the one who lost promised as a punishment to

turn

into a mud salamander.

The

following day the Highest Lord suddenly issued an order saying that the

Dragon

of the Milky Way was to instruct the wind and cloud spirits to send

down three

inches of rain upon the earth.

To

contradict this command was out of the question.

But the

old dragon thought to himself: "It seems that the Dragon-King had a

better

idea of what was going to happen than I had, yet it is altogether too

humiliating to have to turn into a mud salamander!" So he let only two

inches of rain fall, and reported back to the heavenly court that the

command

had been carried out.

Yet the

Emperor Tai Dsung then offered a prayer of thanks to heaven. In it he

said:

"The precious fluid was bestowed upon us to the extent of two inches of

depth. We beg submissively that more may be sent down, so that the

parched

crops may recover!"

When the

Lord of the Heavens read this prayer he was very angry and said: "The

criminal Dragon of the Milky Way has dared diminish the rain which I had ordered. He cannot

be suffered to continue his guilty

life. So We Dschong, who is a general among men on earth, shall behead

him, as

an example for all living beings."

In the

evening the Emperor Tai Dsung had a dream. He saw a giant enter his

room, who

pleaded with hardly restrained tears: "Save me, O Emperor! Because of

my

own accord I diminished the rainfall, the Lord of the Heavens, in his

anger,

has commanded that We Dschong behead me to-morrow at noon. If you will

only

prevent We Dschong from falling asleep at that time, and pray that I

may be

saved, misfortune once more may pass me by!"

The

emperor promised, and the other bowed and left him.

The

following day the emperor sent for We Dschong. They drank tea together

and

played chess.

Toward

noon We Dschong suddenly grew tired and sleepy; but he did not dare

take his

leave. The emperor, however, since one of his pawns had been taken,

fixed his

gaze for a moment on the chess-board and pondered, and before he knew

it We

Dschong was already snoring with a noise like a distant thunder. The

emperor

was much frightened, and hastily called out to him; but he did not

awake. Then

he had two eunuchs shake him, but a long time passed before he could be

aroused.

"How

did you come to fall asleep so suddenly?" asked the emperor.

"I

dreamed," replied We Dschong, "that the Highest God had commanded me

to behead the old dragon. I have just hewn off his head, and my arm

still aches

from the exertion."

And before

he had even finished speaking a dragon's head, as large as a

bushel-measure,

suddenly fell down out of the air. The emperor was terribly frightened

and

rose.

"I

have sinned against the old dragon," said he. Then he retired to the

inner

chambers of his palace and was confused in mind. He remained lying on

his

couch, closed his eyes, said not a word, and breathed but faintly.

Suddenly

he saw two persons in purple robes who had a summons in their hands.

They spoke

to him as follows: "The old Dragon of the Milky Way has complained

against

the emperor in the Nether World. We beg that you will have the chariot

harnessed!"

Instinctively

the emperor followed them, and in the courtyard there stood his chariot

before

the castle, ready and waiting. The emperor entered it, and off they

went flying

through the air. In a moment they had reached the city of the dead.

When he

entered he saw the Lord of the High Mountain sitting in the midst of

the city,

with the ten princes of the Nether World in rows at his right and left.

They

all rose, bowed to him and bade him be seated.

Then the

Lord of the High Mountain said: "The old Dragon of the Milky Way has

really committed a deed which deserved punishment. Yet Your Majesty has

promised to beg the Highest God to spare him, which prayer would

probably have

saved the old dragon's life. And that this matter was neglected over

the

chess-board might well be accounted a mistake. Now the old dragon

complains to

me without ceasing. When I think of how he has striven to gain

sainthood for

more than a thousand years, and must now fall back into the cycle of

transformations, I am really depressed. It is for this reason I have

called

together the princes of the ten pits of the Nether World, to find a way

out of

the difficulty, and have invited Your Majesty to come here to discuss

the

matter. In heaven, on earth and in the Nether World only the gospel of

Buddha

has no limits. Hence, when you return to earth great sacrifices should

be made

to the three and thirty lords of the heavens. Three thousand six

hundred holy

priests of Buddha must read the sutras in order to deliver the old

dragon so

that he may rise again to the skies, and keep his original form. But

the

writings and readings of men will not be enough to ensure this. It will

be

necessary to go to the Western Heavens and thence bring words of

truth."

This the

emperor agreed to, and the Lord of the Great Mountain and the ten

princes of

the Nether World rose and said as they bowed to him: "We beg that you

will

now return!"

Suddenly

Tai Dsung opened his eyes again, and there he was lying on his imperial

couch.

Then he made public the fact that he was at fault, and had the holiest

among

the priests of Buddha sent for to fetch the sutras from the Western

Heavens.

And it was Huan Dschuang, the Monk of the Yangtze-kiang, who in

obedience to

this order, appeared at court.

The name

of this Huan Dschuang had originally been Tschen. His father had passed

the

highest examinations during the reign of the preceding emperor, and had

been

intrusted with the office of district mandarin on the Yangtze-kiang. He

set out

with his wife for this new district, but when their ship reached the

Yellow

River it fell in with a band of robbers. Their captain slew the whole

retinue,

threw father Tschen into the river, took his wife and the document

appointing

him mandarin, went to the district capital under an assumed name and

took

charge of it. All the serving-men whom he took along were members of

his

robber-band. Tschen's wife, however,

together with

her little boy, he imprisoned in a tower room. And all the servants who

attended her were in the confidence of the robbers.

Now below

the tower was a little pond, and in this pond rose a spring which

flowed

beneath the walls to the Yellow River. So one day Tschen's wife took a little

basket of bamboo, pasted up the

cracks and laid her little boy in the basket. Then she cut her finger,

wrote

down the day and hour of the boy's birth on a strip of silk paper with

the

blood, and added that the boy must come and rescue her when he had

reached the

age of twelve. She placed the strip of silk paper beside the boy in the

basket,

and at night, when no one was about, she put the basket in the pond.

The

current carried it away to the Yangtz'e-kiang, and once there it

drifted on as

far as the monastery on the Golden Hill, which is an island lying in

the middle

of the river. There a priest who had come to draw water found it. He

fished it

out and took it to the monastery.

When the

abbot saw what had been written in blood, he ordered his priests and

novices to

say nothing about it to any one. And he brought up the boy in the

monastery.

When the

latter had reached the age of five, he was taught to read the holy

books. The

boy was more intelligent than any of his fellow-students, soon grasped

the

meaning of the sacred writings, and entered more and more deeply into

their

secrets. So he was allowed to take the vows, and when his head had been

shaven

was named: "The Monk of the Yangtze-kiang."

By the

time he was twelve he was as large and strong as a grown man. The

abbot, who knew

of the duty he still had to perform, had him called to a quiet room.

There he

drew forth the letter written in blood and gave it to him.

When the

monk had read it he flung himself down on the ground and wept bitterly.

Thereupon he thanked the abbot for all that the latter had done for

him. He set

out for the city in which his mother dwelt, ran around the yamen of the

mandarin, beat upon the wooden fish and cried: "Deliverance from all

suffering! Deliverance from all suffering!"

After the

robber who had slain his father had slipped into the post he held by

false

pretences, he had taken care to strengthen his position by making

powerful

friends. He even allowed Tschen's wife, who had now been a prisoner for

some

ten years, a little more liberty.

On that

day official business had kept him abroad. The woman was sitting at

home, and

when she heard the wooden fish beaten so insistently before the door

and heard

the words of deliverance, the voice of her heart cried out in her. She

sent out

the serving-maid to call in the priest. He came in by the back door,

and when

she saw that he resembled his father in every feature, she could no

longer

restrain herself, but burst into tears. Then the monk of the

Yangtze-kiang

realized that this was his mother and he took the bloody writing out

and gave

it to her.

She

stroked it and said amid sobs: "My father is a high official, who has

retired from affairs and dwells in the capital. But I have been unable

to write

to him, because this robber guarded me so closely. So I kept alive as

well as I

could, waiting for you to come. Now hurry to the capital for the sake

of your

father's memory, and if his honor is made clear then I can die in

peace. But

you must hasten so that no one finds out about it."

The monk

then went off quickly. First he went back to his cloister to bid

farewell to

his abbot; and then he set out for Sianfu, the capital.

Yet by

that time his grandfather had already died. But one of his uncles, who

was

known at court, was still living. He took soldiers and soon made an end

of the

robbers. But the monk's mother had

died in the meantime.

From that

time on, the Monk of the Yangtze-kiang lived in a pagoda in Sianfu, and

was

known as Huan Dschuang. When the emperor issued the order calling the

priests

of Buddha to court, he was some twenty years of age. He came into the

emperor's

presence, and the latter honored him as a great teacher. Then he set

out for

India.

He was

absent for seventeen years. When he returned he brought three

collections of

books with him, and each collection comprised five-hundred and forty

rolls of

manuscript. With these he once more entered the presence of the

emperor. The

emperor was overjoyed, and with his own hand wrote a preface of the

holy

teachings, in which he recorded all that had happened. Then the great

sacrifice

was held to deliver the old Dragon of the Milky Way.

Note:

The emperor Tai Dining is Li Shi Min, the Prince of Tang mentioned in

No. 64.

He was the most glorious and splendid of all Chinese rulers. The

"Dragon-King of the Eastern Sea" has appeared frequently in these

fairy-tales. As regards the "Lord of the High Mountain," and the ten