| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2011 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER XXVII.

COOK'S RETURN TO HIS HOME. It was a great day in New York when Dr. Cook was welcomed back to his native land. He was hailed as a conqueror; and though the crowd did not crush him and tear his clothing, as a mad rush of the curious did in Copenhagen, enthusiasm in New York was no less fervid. The steamer Oscar II, on which the explorer returned to America, had arrived in the outer waters of New York harbor the evening of September 20. It was not docked, however, until the following morning, since its arrival before Tuesday would have disarranged the carefully laid plans for a grand reception. Dr. Cook's arrival at New York went through progressive stages of enthusiasm as he moved from the lower bay to quarantine, thence to the tug on which his wife and children were waiting to give the first exchange of family endearments, then to the steamer Grand Republic, freighted with more than 1,000 enthusiastic friends and champions of the explorer, and finally, as he set foot on his native soil of Brooklyn and passed through cheering throngs and flower-arched streets, to his home in Bushwick avenue. Everywhere he was met with the same clamorous shouts and demonstrative approval, which swept aside any dissenting note if it existed. Dr. Cook bore his honors calmly and with dignity, smiling upon the crowds, bowing acknowledgments to the oft-repeated cheers and grasping the outstretched hands of friends and strangers. The steamer Oscar II, with Dr. Cook on board, reached quarantine at 6 a. m., and anchored to await inspection by the health officer of the port. Meantime several tugs loaded with passengers hung about the liner. At sunrise the steamer was dressed with flags and preparations were made to receive the explorer's wife and children, who were coming down in a tug, and to meet a reception committee of city officials and friends of Dr. Cook, who went down the harbor on the steamer Grand Republic. Dr. Cook was standing amid a group of passengers on the saloon deck when the health officer boarded the ship. The explorer's face was tinged with a healthy bronze and his demeanor was modest and unassuming. He answered questions freely, but declined to discuss the attitude of Commander Peary. When asked about the controversy over the discovery of the pole, Dr. Cook said: "I have deplored the whole controversy and feel that nothing should be said. I shall leave the public to judge. I feel that the Danish people, who have accepted me without question and have treated me so liberally, should be the first to receive the evidences of my work. "I want to see my wife and family, who, I understand, will come to us first in a revenue tug; then I do not care what comes." Dr. Cook said that during the four months of his stay in Greenland he went over all his notes and data and completed his book describing his trip to the pole. When he was informed that they were close at hand on board the tugboat John Gilperson, his face beamed and he ran to the side of the deck and peered through the mist. Just then, the Gilperson loomed up through the light fog and the figures of his wife and children began to assume definite shapes. When Mrs. Cook and the children could be distinguished the explorer looked down at the little woman, who had smiled unbelievingly when she received reports that he was dead in the Arctic regions, who had wept for joy when the first dispatches of his discovery of the north pole reached her, and who had stood by him when Peary questioned his veracity. He gazed for several seconds without displaying any emotion, save a slight trembling of his hands. Then his eyes began to fill with tears. He pulled off his Derby hat and waved it at his wife. She waved her handkerchief — quickly, eagerly. At the same moment, the Gilperson blew three blasts of its whistle. It was the nautical language for "Glad to see you back." The deep, bass whistle of the Oscar II responded in kind. Dr. Cook then turned to Captain Hempel of the steamship. "I guess I'll go aboard the tugboat right away," he said. The captain grasped his hand. "All right, sir," he replied. Then the captain turned and ordered his men to lower the rope ladders. It had been understood that Dr. Cook was to board the Grand Republic, but it was not yet in sight. Even if it had been. Dr. Cook would not have boarded it. He had eyes only for his wife and little daughters, Helen and Ruth. "You are not timid about descending the rope ladder, are you?" the captain of the Oscar II, laughing, asked Dr. Cook. He smiled, but did not reply. In descending, he unconsciously displayed his great strength. Sometimes he held himself up by his arms like an acrobat hanging from a trapeze. When he reached the bottom of the ladder he leaped lightly to the deck of the tugboat. He turned with his arms outstretched, and his wife threw herself into them. Never before had such a scene taken place on the grimy deck of the tugboat. Here was a man who had received the homage of a King without displaying the slightest trace of sentiment. But now, on seeing his wife, all of his reserve gave way. He was not Dr. Frederick A. Cook, discoverer of the North Pole. He was merely a man who had been separated from his wife and children for more than two years. When he clasped his wife in his arms neither of them uttered a word for some time. Then she murmured: "Oh, Fred," and that was all she could say. Dr. Cook patted her affectionately, but he couldn't say anything. Their two little girls broke the spell that kept their mother and father silent. They rushed up and each seized one of Dr. Cook's hands. "Hello, papa," cried Ruth, the youngest. Helen, the older, then chimed in with a greeting, and Dr. Cook picked Ruth and then Helen up in his arms and kissed them. Meantime the tugboat Gilperson had turned her nose toward New York and started off at full speed. As she left, she gave the Oscar II a parting salute, to which the liner replied. At this time the steamship Monmouth was coming up the bay. She saluted the Gilperson and scores of passengers crowded out on the decks and waved a greeting to Dr. Cook. Every craft in the bay then began saluting the tugboat. When it reached Liberty statue it was met by the Grand Republic. As the tug came up the bay, one man had stood in the background. He was John R. Bradley, the man who financed Dr. Cook's expedition. When Dr. Cook had greeted everyone else Mr. Bradley stepped forward. The two men looked into each other's eyes for a moment and then each took the other by the two hands. They stood that way for fully a minute. All the gratitude that Dr. Cook could express was in his eyes. The words that came to his lips were merely conventionalities. But the two men understood each other. Reporters crowded around Dr. Cook, but he begged to be left alone with his wife and children for a few minutes. With his brothers, William and Joseph, the party then went into the captain's cabin and remained there for fifteen minutes. By that time the Grand Republic, chartered by the Arctic Club of America, was ready to take the Cook party aboard. A companion ladder was lowered from the Grand Republic to the tug, and Dr. Cook climbed up. Mrs, Cook and her party remained on the tug, which followed the Grand Republic as it proceeded up the bay, around the Battery and up the East River amid such a din of whistles, sirens and cheers as seldom has been heard hereabouts. "Bravo, Cook!" "Welcome home!" "We're proud of you!" rang out across the water. Then the words "For He's a Jolly Good Fellow" were sung in chorus by Dr. Cook's fellow passengers on the Oscar II as the tug left the ship's side. The Oscar II immediately weighed anchor and continued up the river to her dock, and Dr. Cook was transferred to the Grand Republic, which was lying a quarter of a mile away. Cinematographs and cameras were turned on him from every point of vantage as he went on board and passed through a guard of honor of the 47th regiment to receive the greeting of the reception committee. On board the Grand Republic Dr. Cook was greeted by the official reception committee and a wreath of roses was placed about the explorer's neck. Standing on the upper deck of the steamer Dr. Cook addressed the committee and his friends as follows: "To a returning explorer there can be no greater pleasure than the appreciation of his own people. Your numbers and cheers make a demonstration that makes me very happy and should fire the pride of all the world. I would have preferred to return first to American shores, but this pleasure was denied me. Instead I came to Denmark and the result has come to you by wire. "I was a stranger in a strange land, but the Danes, with one voice, rose up with enthusiasm and they have guaranteed to all other nations our conquest of the pole. "You have come forward in numbers with a voice appreciating still more forcibly. I can only say that I accept this honor with a due appreciation of its importance. I heartily thank you." The steamer Grand Republic, with Dr. Cook, his wife and children and members of the Arctic Club on board, steamed up the North River from the battery to the foot of West 130th street, where a brief stop was made. The trip up the river was a triumphal one. The Grand Republic was greeted with the siren shrieks of hundreds of craft, small and large. Dr. Cook stood on the upper deck. The steamer after reaching the foot of West 130th street went up the North River as far as Spuyten Duyvil and then retraced its course to the Battery and proceeded up the East River to the foot of South 5th street, in Brooklyn, where Dr. Cook was landed. The ceremonies on the Grand Republic during the three hours that the explorer and the reception party were aboard were necessarily informal, owing to the crowd that pressed about Dr. Cook, all eager to shake his hand and exchange words of greeting. The first person to greet him was Ida A. Lehmann, a daughter of one of his old Brooklyn friends, who had been delegated to decorate the explorer with a wreath of roses, in accordance with a custom followed at Copenhagen. As Miss Lehmann threw the garland about Dr. Cook's neck, she said: "You hero of the north, come to us, your friends, associates and business acquaintances of your own neighborhood, Bushwick. Your record with us was one of honor, character and conscience, and your word the synonym of truth. We believe you from the far north, and are here to proclaim you a 'gentleman of Bushwick!' " Dr. Cook wore the garland during the rest of the reception ceremonies. Bird S. Coler, borough president, welcomed the explorer aboard the steamer on behalf of the borough of Brooklyn. "I regret," he said, "that we have not a mayor as big as our town to receive you. You are not only a great explorer, but a thorough American gentleman, and Mrs. Cook is a thorough American lady." Speaking for the Arctic Club of America, Capt. Bradley S. Osbon, its secretary, read a letter from the president, Rear-Admiral Winfield Scott Schley, in which the admiral expressed regret that his health made it impossible to be present. "I hope you will carry to Dr. Cook," he said, "my congratulations and abiding faith in the great achievement he has accomplished." One of the first to greet Dr. Cook after the speechmaking was over was his sister, Mrs. Joseph Y. Murphy of Tom's River, N. J. The bronzed explorer took her in his arms and hugged and kissed her regardless of the cameras trained upon him. After that he kissed his niece, Miss Lilyn Murphy, and shook hands with Joseph Murphy, his brother-in-law. It was a disheveled discoverer that finally retired to his cabin, where he remained during the rest of the voyage up and down the North River. Dr. Cook did not appear on deck again until the steamer approached the pier at the bottom of South 5th street, Brooklyn, where the local reception committee was gathered to receive him. It was still half an hour before the time fixed for his landing, however, so the Grand Republic kept on up the river, while the band on deck played "Auld Lang Syne" and "Home, Sweet Home," and Dr. Cook with his family and a few others stood in the pilot house, where they were in view of the thousands gathered on the Brooklyn shore. The steamer turned and came back to land the party at 11.35. About 100 automobiles and 5,000 persons were on the pier and along South 5th street when Dr. Cook landed. There was a rush to see him and to form a parade. After much confusion the police made a passage for an automobile carrying the explorer, and the other vehicles, headed by a band, fell into a line a mile long. The parade passed through five miles of cheering, crowded streets. At Dr. Cook's former home in Bush wick avenue the procession passed under an arch bearing the inscription: "We believe in you." Thousands of school children lined Bushwick avenue and cried "Cook! Cook!" as the explorer passed on his way to the Bushwick club, where a reception in his honor was held during the remainder of the day. Dr. Cook gave out the following signed statement: "On Board the Oscar II. — After one of the most delightful trips of my life across the Atlantic, I am indeed glad once more to see the shores of my native land. I have come from the pole. I have brought my story and my data with me. The public has already a tangible and a specific record of that trip. In a short time, the narrative, with all the observations, will be published and placed before the world for examination. "It is as easy for you as for me to understand why I cannot, on the impulse of the moment, read off a manuscript which covers the work of two years. As said upon several occasions, all the charges, accusations and expressions of disbelief are based upon entire ignorance of the supplementary data which i possess. "No one who has spoken or written on the subject in opposition to my claim knows of the facts with which such work of exploration is measured. All of the criticisms have been based upon obvious errors in the reproductions of my first dispatch or upon the discussions of petty side issues presented by unfair critics. "The expedition was private. It was started out without the usual publicity bombast. John R. Bradley furnished the money and I shaped the destiny of the venture. For the time being it concerned us only, but the results were so important that on returning I at once placed before the public a report containing the main outline of the work. 'T have not come home to enter into arguments with one man or with fifty men, but I am here to present a clear record of a piece of work over which I have a right to display a certain amount of pride. When scientists study the detailed observations and the narrative in its consecutive order I am certain that in the due course of events all will be compelled to admit the truth of my statement. "I am perfectly willing to abide by the final verdict of this record by competent judges. That must be the last word in the discussion and that alone can satisfy me and the public. "Furthermore, not only will my report be before you in black and white, but I will also bring to America human witnesses to prove that I have been to the pole. FREDERICK

A. COOK."

"I shall await events," said Dr. Cook just before he left the deck of the Oscar II to be taken to the city by the welcoming committee. "When my material has been got together and put into shape it will be submitted in the first instance to the University of Copenhagen. After that it will be laid before the geographical societies of the world. I will not consent to submit any fragmentary portions of my observations or my records to any one. The report and all the data connected with my trip must be examined in their entirety, together with my instruments, some of which I have in my possession now and others of which are on their way to America at the present moment. These will all be properly controlled and tested before submission to the scientific bodies." Asked for what reason he did not immediately give full details of his achievement, Dr. Cook said: "I have given to the public a concise account of my journey similar to that always given by explorers on their return from a journey of exploration. For the present no other details are necessary and, as a matter of fact, no further specific evidences of my claim have been called for from any side. It has never been customary hitherto for explorers to make their full records public in such haste. As a rule, scientific societies are not remarkable for their rapidity in coming to conclusions, and they are usually content to wait until complete data are compiled,"

Courtesy of "Leslie's Weekly." 1909.

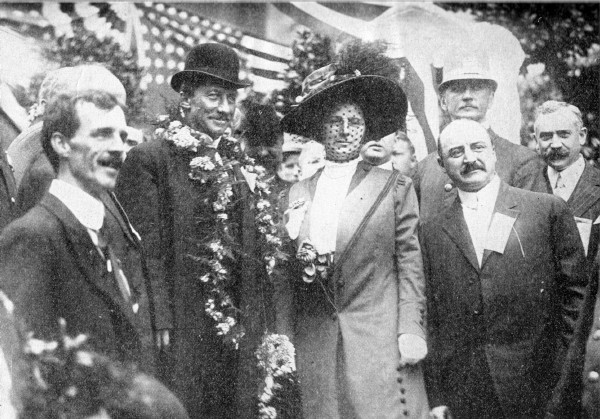

DR. FREDERICK A. COOK DECORATED

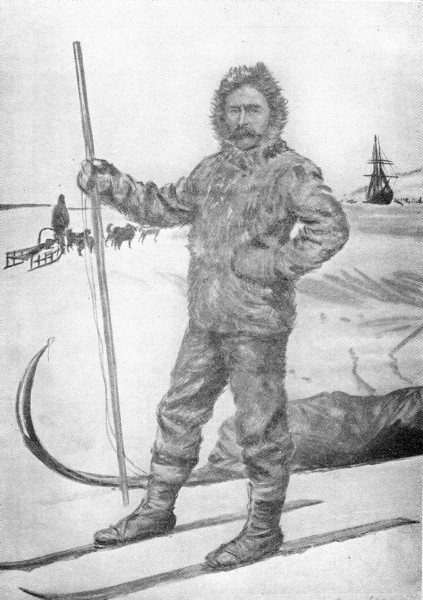

WITH THE GARLAND OF HEROES.Photograph of Dr. and Mrs. Cook and the officers of the Bushwick Club, Dr. Cook's home folks. They followed on ancient custom of Denmark and placed a garland of flowers around their hero.  COMMANDER ROBERT E. PEARY, U. S. N., READY FOR THE DASH TO THE POLE. In regard to the full recognition of his feat by Denmark, Dr. Cook remarked: "Daagaard-Jense, inspector of Danish North Greenland, after hearing Rasmussen and talking with Gov. Kraul of Upernavik, who has seen and read the entire record, telegraphed to the Danish government in Copenhagen his assurance of the truth of my declarations and guaranteeing them as authentic. The Danish authorities in Greenland, who are in reality the advisers of the Danish government, have been for nearly four months in possession of all details of my trip. The Danish government and the University of Copenhagen, as well as the Danish Geographical society, have, on their report, taken over the virtual guaranty for the sincerity and authenticity of my records. They have stood up for them, so to speak, before the world. They do not ask me to furnish any further proofs or evidence of any kind, but in justice to Denmark, it is my intention to place the first completed record of my polar journey at the disposal of the University of Copenhagen." On September 22 Dr. Cook cheerfully submitted to a gruelling cross examination by forty inquisitors of the daily and periodical press, and before the interview came to a close he had converted even several arrant sceptics into enthusiastic partisans of his right to the title of discoverer of the North Pole. It was an occasion for which there had been ample preparation, for the questioners had been informed the day before that he would receive them and they had meanwhile taxed their ingenuity with the devising of all manner of interrogatories and with the aid of geographied experts had prepared test questions. Every one present had framed inquiries which bore upon some point in the accounts of the discovery, which was not quite clear to them. For an hour and a half this business of quizzing proceeded and, in parting, the explorer was surrounded, not by analysis, but by eager converts, several, who were commissioned by their editors to doubt, were wringing Dr. Cook by the hand and expressing their unqualified personal belief in everything he had said. He referred quite casually to the writing of his experiences and at the request of one of the reporters brought out one-third of the manuscript which he had prepared prone upon the floor of a hut with a flat stone for his desk and a blubber lamp for his light. He had with him three small memorandum books, five by eight inches, containing two hundred leaves each. To these he had committed his diary in pencil, for ink will not withstand the Arctic chill. When his enforced sojourn in the frozen North gave him time for literary labors he had written 100,000 words in these memorandum books between the lines of what he had already jotted down. The chirography was almost microscopic and often hundreds of words were crowded together like a multitude of pigmies taking their morning walk on paper. The scarcity of pages had compelled from the Arctic explorer an economy which caused him to rival the ingenuity of those patient men who write the Decalogue on the back of penny postage stamp. "That's enough for me," said one hard headed Thomas, who had leaved over the record. "No man alive would sit up nights doing this kind of thing for fun." Dr. Cook entered the room, where the interviewers were assembled, accompanied by his secretary, Mr. Walter Lonsdale, of the American Legation in Copenhagen and by his daughter Ruth. The child remained with him a few minutes. The explorer said he would prefer to have one man ask the questions, but as all had something on their minds he addressed himself to each interrogator in turn, looking him squarely in the eye and speaking in incisive, clear cut sentences. "What was the reason," he was asked, "that you imposed secrecy upon Mr. Harry Whitney and young Pritchard on your return from the pole?" "I do not think," he answered, "that I was bound to disclose to Mr. Peary the nature of my work, and he might have found out about it on his arrival at Etah. I told Mr. Whitney that he was at liberty to give to the world all that he knew after I had given the announcement first to the world. I knew Mr. Whitney would probably not be back to civilization before the middle of October. The Jeanie, on which he is aboard, is now following out the programme as I understood it. He told me he was going to the American side and to Hudson Bay to hunt, and the understanding when I started for home was that he was not to write anything which would get to civilization or to Mr. Peary before I did." "Why did you not wish Mr. Peary to know?" was the question. "Why should I," was the answer, "give to Mr. Peary any information before I gave it to the world?" "Did you think that Mr. Peary would make any improper use of it?" was asked. "I don't think so," was the reply. Dr. Cook was asked if he had any comment to make on the fact that Commander Peary had decided to accept no dinner invitations until the "controversy" concerning the discovery of the North Pole was settled. The Brooklyn explorer said that he had never heard of it and that he had no comments to make. He said there had never been any trouble between Mr. Peary and himself. "Do you," one interrogator began, "consider Commander Peary your enemy or your friend?" "I don't know," he replied, "I always treated him as a friend and until I know more about the situation I shall continue to do the same."

Here are some of the more important questions with the replies of Dr. Cook: Q. Did you ever say anything at Etah that indicated that you feared for your life if Commander Peary got there? A. No. Q. Would you be willing to meet Mr. Peary in a debate when he gets here? A. As far as I am concerned the Peary incident is closed. Mr. Peary is not the dictator of my affairs, and I do not care to say anything further about him. Q. Did you know Mr. Whitney when you had met him on your return to Etah? A. No; he introduced himself, but I did not catch his name and did not know it until the following day. Q. Did you know that Mr. Peary was going to start up at that time? A. No, I did not know. Q. What caused you to have such confidence in Mr. Whitney that you entrusted your instruments to him? A. I knew him by name, and circumstances that arose while I was with him justified my confidence. I gave him the instruments to bring back because I thought they would be less liable to injury on board his vessel than if I took them across glaciers and rough ice covered country. Q. What is your opinion of the story told by the negro Henson of the information he obtained from your two Eskimos? A. Well, the Eskimos were bound down by me not to tell any one where they had been. I should like you to have Henson here and cross-question him yourself. Henson's testimony is entirely founded on hearsay. Q. Knowing that a ship was coming north this summer for Mr. Whitney, why did you not wait for that ship and come direct to New York instead of going to South Greenland and from there to Copenhagen? A. I knew that the Danish government ship would get me home before Whitney's ship.

Q. What instruments did you have with you from Cape Thomas Hubbard and back? A. Sextant, artificial horizon, three compasses, three chronometer watches, thermometers, barometers and a pedometer. Q. What kind of sextant did you have and how many? A. One sextant — a French apparatus. Q. What kind of artificial horizon did you have? A. Glass. Q. What kind of transit or theodolite did you have and how many? A. We didn't use any. Q. What kind of compass did you have? A. We had one liquid compass and one surveying compass. Q. What kind of compass did you use to determine your compass variation? A. Surveying compass; it had an azimuth attachment. Q. What compass course did you take from Cape Thomas Hubbard north? A. Well, that changes every day. If you follow the course on a map you have got the compass course. Q. Was your determination of the pole solely by an observation of the sun's altitude, or did you take observations of the pole star twelve hours apart, and by the determination of the celestial pole midway between the two positions prove the accuracy of your position on the terrestrial pole? A. How are you going to take an observation by the polar star when you have a continuous sun? There is no night; you cannot have any stars; there is no darkness. Q. What other kind of observations did you make at the pole and how many? And what was the altitude of the sun?

A. We have told that the altitude of the sun gave us our positions; that is all there is to say about that. We made regular astronomical observations, such as would be made by the compass and other instruments. We merely made the nautical observations that a captain would have made aboard a ship. Q. Will you describe in detail any single observation taken by you at the North Pole, with the exact figures of the results and the corrections applied? A. Not at this present moment. We will describe every one of them in detail when they go to the University of Copenhagen. They will go there within two months. The entire records will be delivered to the university, and after that they will go to everybody that wants to examine them. Q. In your original narrative you said: — "The night of April 7 was made notable by the swinging of the sun at midnight over the northern ice. Our observation on April 6 placed the camp in latitude 86.36, longitude 94.2." The astronomers say that in the latitude you mention the midnight sun would have been visible on April i and that if you really saw it for the first time on April 7 you must have been 550 miles from the pole instead of 234, as you supposed. Therefore to have reached the pole on April 21 you would have had to travel thirty-nine miles daily. What is your explanation of the apparent discrepancy? A. In the first place, that indicates the point I have taken; that nobody can pronounce judgment on a matter of this kind until they get the complete record. The northern horizon at midnight had been so obscure that we could not tell whether the sun was below the horizon or above it. We were not making observations at midnight. Therefore this statement is based on the fact that we have said that it was possible to see the sun on midnight of that day. I have not looked through the Herald's story, as it has been written out in full. My impression is that we were absolutely unable to see the sun the midnight before that. The horizon was obscured. Dr. Cook in reply to several questions said that he could not have gone back to civilization any sooner than he did. "Unless," he began, "I started through the ice for three hundred miles in an open boat and went to — Well, no, just take that out; I could not have got back any sooner." He described in detail his provisioning for the final journey. He had started from Greenland with eleven sledges, 103 dogs and eleven Eskimos, and had started on his last stage northward with two Eskimos and twenty-six dogs and two sledges, on which were laden rations for eighty days. He had made the calculation of the food supplies, too, on the basis that dog would eat dog. Speaking of the land which he had discovered between latitude 84-85 and the 102d meridian, Dr. Cook said that it was mountainous on the eastern coast. He saw it at a distance of about forty miles. "Why didn't you explore it?" was one of the inquiries. "If I had," he answered, "I should have never found the pole." His attention was called to a quotation from one of his books on the Antarctic, in which he referred to his taking a few observations himself, as that work was distributed among the members of the party. Q. Do you think that on account of your lack of experience that your observations might be erroneous? A. A full investigation of those observations which are to be presented first to the University of Copenhagen will show if that is the case. Dr. Cook recounted in graphic language his meeting with Mr. Whitney. An Eskimo had sighted the explorer at a distance of five miles on the ice, and Mr. Whitney had come two miles to meet him. Dr. Cook had then only half a sledge. Referring to a dispatch in the Herald in which it was said that doubt had been cast upon his trip to the North Pole on account of the condition of his equipment when he returned, Dr. Cook at once replied: "I do not see what they could expect. We came back to Etah with half a sledge. Our sleeping bags had been fed to the dogs. We were ourselves dragging what was left of the sledge and the instruments and records. We had come back to land from the pole with two sledges. Dr. Cook said he had with him a folding boat of canvas, by means of which he was able to cross leads, and this he had carried with him to the pole. Speaking of the conversations he had with Mr. Whitney relative to his discovery, he said that later he questioned Pritchard, one of the Peary sailors and learned that he was about to send a letter to his mother telling of the discovery of the pole. He had Pritchard leave out this paragraph for fear the letter might by some chance get to civilization sooner than he did. The Danes of Greenland, Dr. Cook explained, knew of the discovery four months ago, but he felt reasonably sure that he could get back to civilization with the news quicker than any rumor could reach. As to what Murphy, the boatswain of the Roosevelt, might be able to communicate, Dr. Cook had no fear, as that worthy could neither read nor write and he knew who pencilled his letters for him. "I think that on the whole," added Dr. Cook, "I have a right to announce my own news." Dr. Cook's attention was called by one of the reporters to an assertion in the first instalment of his narrative in the Herald, to which he had referred to the secrecy of his preparations at Gloucester, which had been made even then with the conquest of the pole in view, while in the second instalment he spoke of his purpose to reach the pole as an after thought, occurring to him on the shores of Greenland. "Well," replied the explorer; "we prepared in New York. We did not ask the government for funds; we took no private subscriptions. We were, therefore, not responsible to any one and did not have to tell of our movements. The business concerned us only. We prepared for every emergency when we left here; we arranged for a supply of provisions and for material with which to make sleds and camp work. \Mien you have done that you have done all that was necessary for polar expeditions. As to the other part of the question, we have told and told very completely why we started out for the pole at that time. It was simply because we found a condition which was unusually favorable. The best natives and the best dogs were there within seven hundred miles of the pole. It was a condition which I have never seen before nor since. The Eskimos were very unsuccessful at that point two years before and two years since we have been there." Still further light was thrown upon his trip by Dr. Cook in a speech at a banquet tendered him September 23 by the Arctic Club of America. Upon his claim the organization, composed of men who have explored the frigid seas, placed the imprimatur of its approval as the one who "first" was on the "upper edge" of the earth. With them was a brilliant assemblage of the men and the women of this city, who joined with the veterans of polar endeavor in giving enthusiastic welcome to the returned explorer. Twelve hundred persons, the second largest company ever assembled at a public dinner within those walls, pressed about the man who had found the hyperborean realm, after he had made his response to their greetings, and overwhelmed him with expressions of confidence and good will. Side by side with the men who guide the destinies of New York and with women of society stood survivors of the Greely expedition and of the quest which Mr. Peary led. With characteristic modesty Dr. Cook gave credit for his discovery to the polar explorers who had gone before and by whose hard-won knowledge and heart-breaking errors he had learned; to his friend and backer, John R. Bradley; to the Canadian government, to the wild men of the North and last of all, a casual mention of himself as the one who had at last achieved. He sought no license of his quest, as he plainly said, and he showed a calm indifference to captious criticism. Everywhere about him were the flags of his own land intertwined with the banner of Denmark — the country which had first received him and approved him as the finder of the axial terminus of the world. By his side sat Rear Admiral Schley, the rescuer of the Greely expedition; before him were friends and comrades of the arctic circle and leaders of the scientific world and beyond, in a box at the center of the balcony, was the wife whose devotion had inspired his achievement. Few and eloquent were the words with which the rear admiral introduced Dr. Cook, the keynote of which was that he regretted that controversy should have arisen concerning so gallant a feat, and he repeated the words which came to him as from the past that there was "glory enough for both." Cheers rang through the hall; men and women rose to their feet and joined in the refrain, "For He Is a Jolly Good Fellow," as the explorer rose to his feet. The applause lasted for several minutes, and then, when his auditors paused for breath, Dr. Cook read his speech in a slow, even voice. Dr. Cook's speech was interrupted in the middle by his reference to his backer, John R. Bradley, who had gone from his place at the principal table to a group of his friends on the floor. "Bradley! Bradley!" called many a voice, "Bradley, show yourself!" And finally he was obliged to stand upon a chair and bow his acknowledgments to the tumultuous cheers. All that Dr. Cook said carried with it conviction, and when he finished with his tribute to the brave men who had gone before and his disclaimer for more than his share of the glory the company hailed him with every expression of confidence. It was plain that they agreed with all that Rear Admiral Schley said in his speech of introduction. "I regret," the admiral said, "that there should have been any issue raised concerning an achievement so full of glory for both. As president of the Arctic Club of America, I believe that both Dr. Cook and Mr. Peary found the pole. They succeeded in reaching that point in the frozen seas which was so long the goal of the cherished ambitions of mankind. "Both endure inconceivable hardships under trying circumstances. These two men reached the pole — men willing to venture into fields of prolific danger; men who were strong and able to penetrate the farthest north and to bring back to you the story of what they have seen; all honor to them both. And, my dear friends, I now have the honor to introduce to you the man who first discovered the north pole." Dr. Cook in his address said: "This is one of the highest honors I ever hope to receive. You represent most of the frigid explorers of Europe and nearly all of the Arctic explorers in America. Your welcome is the explorer's guarantee to the world — coming as it does from fellow workers, from men who know and have gone through the same experience — it is an appreciation and a victory the highest which could fall to the lot of any returning traveler. 'The key to frigid endeavor is subsistence. There is nothing in the entire realm of the Arctic which is impossible to man. If the animal fires are supplied with adequate fuel there is no cold too severe and no obstacle too great to surmount. No important expedition has ever returned because of unscalable barriers or impossible weather. The exhausted food supply resulting from a limited means of transportation has turned every aspirant from his goal. In the ages of the polar quest much has been tried and much has been learned. The most important lesson is that civilized man, if he will succeed, must bend to the savage simplicity necessary. "The problem belongs to modern man, but for its execution we must begin with the food and the means of transportation of the wild man. Even this must be reduced and simplified to fit the new environment. With due respect to the complimentary eloquence of the chairman and others, candor compels me to say that the effort of getting to the pole is not one of physical endurance, nor is it fair to call it bravery; but a proper understanding of the needs of the stomach and a knowledge of the limits of the brute force of the motive power, be that man or beast. "Our conquest was only possible with the accumulated lessons of early ages of experience. The failures of our less successful predecessors were stepping stones to ultimate success. The real pathfinders of the pole were the early Danish, the Dutch, the English and the Norse, Italian and American explorers. With these worthy forerunners we must therefore share the good fruits which your chairman has put into my basket. "A similar obligation is due to the wild man. The twin families of wild folk, the Eskimo and the Indian, were important factors to us. "The use of pemmican and the snowshoe, which makes the penetration of the Arctic mystery barely possible, has been borrowed from the American Indian. The method of travel, the motor force and the native ingenuity, without which the polar quest would be a hopeless task, have been taken from the Eskimo. To savage man, therefore, who has no flag, we are bound to give a part of this fruit. "To John R. Bradley — the man who paid the bills — belongs at least one-half of this fruit. "The Canadian government sent its expedition under Captain Bernier 1,000 miles out of its course to help us to it. I gladly pass the basket. In returning, shriveled skin and withered muscles were filled out at the expense of Danish hospitality. And last, but not least — the reception with open arms by fellow explorers — to you and to all, belongs this basket of good things which the chairman has placed on my shoulder.

"Nothing would suit me better than to tell you to-night the complete story of our quest, but the very first telegram gives more specific data than I could hope to tell you in an after-dinner address. Therefore, I shall devote the allotted time to an elucidation of certain phases of our adventure. "One of the most remarkable charges brought out is that I did not seek a geographic license to start for the pole. Now, gentlemen, to the large public that may be a mystery, but you who know will appreciate that no explorer can start and say that he will reach the pole. Many good men have tried before; all have failed. All who understand the problem know that success is but barely possible when every conceivable circumstance is favorable. It is only necessary to make announcement that an expedition embarks for the pole to start an undesirable bombast and flourish of trumpets. This I chose to escape. "Mr. John R. Bradley furnished the funds. I shaped the destiny of the expedition. For the time being the business concerned us only. I believed then, as I believe now, that if we succeeded there would be time enough to fly the banner of victory. You are here to-night. Mr. Bradley is here, and I am here. We have come together to celebrate that victory. "Now, gentlemen, I appeal to you as explorers and as men. Am I bound to appeal to anybody, to any man, to any body of men, for a license to look for the pole? "Another criticism is the charge of our insufficient equipment. We have met this. You know that we had every possible aid to success in sledge traveling. A big ship is no advantage. An army of white men, who at best are novices, is a distinct hindrance, while a cumbersome luxury of equipment is fatal to progress. We chose to live a life as simple as that of Adam, and we forced the strands of human endurance to scientific limits. If you will reach the pole there is no other way. For our simple needs Mr. Bradley furnished sufficient funds. We were not overburdened with the usual aids to pleasure and comfort, but I did not start for that purpose. "Now, as to the excitement of the press to force things of their own picking from important records into print. In reply to this I have taken the stand that I have already given a tangible account of our journey. It is as complete as the preliminary reports of any previous explorer.

"The data, the observations, the record, are of exactly the same character. Heretofore such evidence has been taken with faith and the complete record was not expected to appear for years, whereas we agree to deliver all within a few months. "Now, gentlemen, about the pole. We arrived April 21, 1908. We discovered new land along the 102d meridian between the eighty-fourth and the eighty-fifth parallel. Beyond that there was absolutely no life and no land. The ice was in large, heavy fields with few pressure lines. The drift was south of east, the wind was south of west. Clear weather gave good regular observations nearly every day. These observations, combined with those at the pole on the 21st and 22d of April, are sufficient to guarantee our claim. When taken in connection with the general record, you do not require this. "I cannot sit down without acknowledging to you, and to the living Arctic explorers, my debt of gratitude for. their valuable assistance. The report of this polar success has come with a sudden force, but in the present enthusiasm we must not forget the fathers of the art of polar travel. There is glory enough for all. There is enough to go to the graves of the dead and to the heads of the living." |