| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2011 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

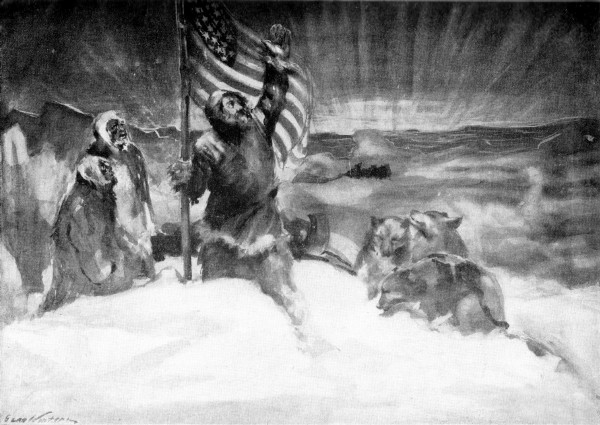

| CHAPTER XXVIII.

PEARY WELCOMED HOME. While Dr. Cook was being greeted by his friends and admirers in New York, similar honors were being paid to Commander Peary in Sydney, N. F., the port he had left more than a year before on the quest that was to prove so notable, Peary had been awaited for some days in Sydney. At an early hour on the morning of September 21, when the Roosevelt was still edging her way along the Cape Briton coast, the steam yacht Sheelah, owned by James Ross, president of the Dominion Coal company, put to sea carrying Mrs. Peary, her daughter, Miss Marie Peary, little Robert E. Peary, Jr., and a party of friends, all eager to meet the returning explorer. Among those on board were Col. Borup, father of George Borup, a member of the Peary expedition; George Kennan, the author, and John Kehl, the United States consul at Sydney. As the Sheelah drew alongside the Roosevelt outside a sailor on the yacht hailed the arctic ship. In reply Commander Peary came to the rail and was greatly surprised when he perceived his wife and children waving their greetings. In reply the explorer waved his slouch hat and called to them to come on board. A few words of welcome were exchanged while the boat was being lowered. Mrs. Peary, Miss Peary and the little boy, accompanied by Col. Borup, then went over the side of the Sheelah, took their places in a small boat and were rowed over to the Roosevelt. In the meantime Commander Peary had retired to the cabin. Mrs. Peary and the children were assisted up the side of the Roosevelt and made their way across the deck to greet the husband and father in private. The Sheelah then put on full steam and returned to Sydney, while the Roosevelt came along at slower speed. Commander Peary had decorated his ship for the occasion and in addition to the flags of the United States and the Dominion of Canada, the Roosevelt flew the burgee of the New York yacht club and the flag of the Peary Arctic club. The American flag waving at the peak of the spanker gaff of the Roosevelt attracted much attention. It bore a diagonal white band on which were the words, "North pole," in black letters. A newspaper correspondent boarded the Roosevelt at North Sydney and received from Commander Peary a new version of the dispute regarding Dr. Cook's supplies at Annotook. The explorer's attention was called to a statement received by wireless telegraphy from Dr. Frederick A, Cook, on board the steamer Oscar II, declaring that the Eskimos at Annotook had informed Peary that Cook was long since dead. Peary was asked if he entertained this opinion, and said no. On the contrary, he had left supplies at Etah in case, as might well happen. Dr. Cook should return there without food. Meanwhile the news that the Roosevelt was only twenty miles away spread quickly, and groups of people gathered at the water front to take part in the welcome. The day was perfect and the harbor presented a beautiful spectacle, as all manner of water craft, yachts, sailboats and motor boats, displaying their colors, made their way down the bay to escort the Roosevelt to her dock. The tug C. M. Winch conveyed the official welcoming party down the bay. This party included the mayor of Sydney, Wallace Richardson; the heads of the various city departments, and other prominent officials. As the morning advanced business in Sydney came to an end. Stores were closed, the hotels were emptied of their guests, and the crowd on the water front increased rapidly. Commander Peary's trip up Sydney harbor was one continual ovation. When the Roosevelt turned the point off the city the whistles of the steel works, all the steam vessels in port and the colliers united in one immense and sustained volume of sound, and the crowds that filled the esplanade and wharves cheered continuously as the arctic steamer swept slowly along. A fleet of tugs accompanied the Roosevelt up the bay and scores of carriages that had gone down to the point were driven hastily back to town and discharged their occupants, who hurried to the water front. Consul Kehl boarded the Roosevelt down the bay and welcomed Commander Peary on behalf of the American government and the American residents of Sydney. There were no important officials of the Dominion government present to greet the explorer. The Roosevelt proceeded direct to the ferry wharf, where 2,000 school children had been assembled. Each carried an American flag and the emblems were waved in unison the moment the explorer stepped ashore. A delegation of ten school girls dressed in white then went forward and while Commander Peary stood at attention before them Miss Naomi Kehl, daughter of the American consul, recited a short address of welcome and presented the commander with a beautiful bouquet. The party then entered carriages and were driven to their hotel. The police had to clear a way for them through the crowd of 10,000 people that filled the square. At the hotel Commander Peary was welcomed by the city aldermen. At the hotel Commander Peary was soon holding an impromptu reception. Standing on the steps of his carriage, he shook hands with scores of people who struggled to reach him. Rising in his carriage, Mayor Richardson read an address of welcome from the citizens of Sydney congratulating Commander Peary on his success in reaching the pole and his safe return and wishing him and the members of his family good health and a long life. Commander Peary expressed his appreciation of the welcome extended him. Eleven times, he said, he had sailed from Sydney for the north; once he had returned with "farthest north" and now he came back with the pole itself. At the conclusion of the handshaking and greetings Commander Peary retired to his room. The Roosevelt had passed the previous day at St. Paul's island and James Campbell, superintendent of the Canadian government station there, entertained Capt. Robert Bartlett and Prof. McMillan of the Peary expedition at his residence on shore. As soon as his guests were in his house Mr. Campbell turned to them and said: "Now, gentlemen, this island is yours; what is the first thing you want?" Without a moment's hesitation and in unison Capt. Bartlett and Prof. McMillan replied: "A glass of real milk." Commander Peary, after leaving Sydney, made a kind of triumphal tour through Maine on a railroad train. On his arrival in Portland the evening of September 23, Peary was given an enthusiastic welcome by a large portion of the population. He was met at the station by Mayor Leighton and the reception committee in carriages and escorted to the Auditorium, where he held a public reception. Four companies of militia and a long procession of residents, all carrying red fire, marched behind the carriages. The streets from the station to the Auditorium were lined with people. Thousands cheered the explorer as he passed. After the reception Commander Peary was banquetted by the cities of Portland and South Portland. At this function he was vociferously applauded by the diners and complimented by half a dozen speakers, including Gov. Fernald and President William Dewitt Hyde of Bowdoin college. It was midnight before the dinner was over and the speechmaking began. The last speaker was the explorer himself. When he arose he was generously acclaimed. "You know, as do I, today has been a white letter day for me," said Peary. "The splendid demonstration in this city, every foot of which I knew in my boyhood days; this splendid gathering here, that striking loyalty from the governor straight from the shoulder, the fine tribute from Mayor Leighton to Mrs. Peary, who has endured as much as I in this effort, have touched my heart as they will touch hers. "I have been asked, 'What is the scientific value of the discovery of the north pole?' There are some things about it that are a great deal greater than the gathering of a few additional data about the earth. As long as there was a part of the earth undiscovered is was a reproach on humanity and a challenge to civilization. Another thing, it has accredited to the United States another milestone in history. "Another fact is the satisfaction that at last a man, in spite of every obstacle, has made good." During the journey through eastern Maine Commander and Mrs. Peary, with their children and newspaper men, occupied the chair car of the St. John express and overflowed into other coaches. Along the 350 mile route Peary was cordial and appreciative, although he appeared tired. At every station there was a cheering crowd. At Old Town the first big demonstration on this side of the border was made. At Bangor the explorer was welcomed by thousands, and when he walked into the concourse from the train shed was given a succession of cheers. Mayor Woodman escorted him to a carriage, and, with Gen. Hubbard and members of the city council in other carriages, he was driven to a hotel, where he was entertained at luncheon. He was presented with a large silver loving cup. Commander Peary left Bangor at 3 40 p. m. on the Bar Harbor-New York express, after a stop of three hours. At Waterville he was officially welcomed. Members of the city government in carriages, over 1,000 school children on foot, headed by a band and escorted by a company of the national guard, marched to the station, where a stand had been erected. When the train arrived the commander was escorted to the stand by Mayor Redington. The school children, each carrying an American flag, were banked about the stand, with the guardsmen around them. As Peary mounted the stand the children cheered and waved their flags. Several thousand persons joined in the cheering. Captain Robert Bartlett, who piloted the Roosevelt through the frozen North, told at Sydney how Commander Peary turned him back from the pole. He said: "I really didn't think I would have to go back until I had reached the eighty-eighth parallel. The commander then said I must go back — that he had decided to take Matt Henson. "I — well, it was a bitter disappointment. I got up early the next morning while the rest were asleep and started north alone. I don't know, perhaps I cried a little. I guess, perhaps, I was just a little crazy then. I thought that perhaps I could walk on the rest of the way alone. I seemed so near. "Here I had come thousands of miles, and it was only a little over a hundred more to the pole. "Commander Peary figured on five marches more, and it seemed as if I could make it alone, even if I didn't have any dogs or food or anything. "I felt so strong I went along for five miles or so, and then I came to my senses and knew I must go back. "They were up at the camp then and getting ready to start. Never mind whether there were any words or not. I told the commander if I was going to be any hindrance and perhaps make a failure out of it I would turn around and go back. He said I must go, so I had to do it. But my mind had been set on it for so long I had rather die than give it up then. "When I started on the back trail I couldn't believe it was really true at first, and I kind of went on in a daze. I can tell you every lead we crossed and just how far we went on every march and all about the ice on the trip up, but as I thought of it afterward I could not remember anything about coming back until I got to the ship. Then I heard of poor Marvin, and almost envied him. But that distracted my mind until the boss returned, and then I was busy getting the Roosevelt through the ice."  THE STARS AND STRIPES, THE FIRST FLAG AT THE POLE.  HOME SWEET HOME. Dr. Cook in automobile passing under the magnificent triumphal arch erected near his home by neighbors and friends in Bushwick, a suburb of Brooklyn, N. Y. |