|

CHAPTER III

HYACINTH OR IRIS?

HYACINTHUS, beloved of Apollo, accidentally met death at the hands of

that god, through the interposition of jealous Zephyr. Apollo, after

grieving for his favourite, cried to his blood: "Thou shalt be a new

flower inscribed with my lamentations!" and immediately after, "Behold

the blood shed on the grass ceases to be blood, and a flower springs

forth more beautiful than Tyrian dye, and takes the same form as the

lily, save that the lily is silvery white and this is purple. Phoebus

himself writes his own lamentations upon the petals, and Ai! Ai! is

written upon the flower."

But it

was very long ago when Ovid told this tale of the childhood of the

world, and in the course of the centuries some names get lost and some

misapplied; the question is, what flower is it that sprang from the

dead boy's blood? A flower that is purple -- and the Greek purple,

which included many shades of red -- was a colour in no way related to

the French greys and violet blue that are all our hyacinths can show,

but which is the colour of the common purple iris. A flower that was

like a lily, which our hyacinth is not, excepting only the lily of the

valley -- a solitary and most untypical lily in its way of blooming;

but which an iris may be taken to be, seeing its long confusion and

identification with the lilies of France. And a flower that

memorialised the sun-god's grief, and was inscribed with signs of it:

an inscription on the hyacinth is hard to seek, for though it is true

some learned person has given the common wood hyacinth the surname

Non-scriptus, what one, especially if one were a grower, would

really like to see, is a hyacinth that is scriptus.

The iris, on the other hand, has well-defined marks upon it, such as

fancy can easily make sign-writing of sorts; which, indeed, fancy has

so made in other tales -- the tale of their springing from Ajax's blood

and bearing his name upon them, and the tale of their growing from the

grave of the illiterate saint, and being marked with Ave Maria, the

sole words of prayer he knew. From all of which it seems one must

conclude that the flower called forth by Phoebus Apollo when Hyacinthus

died was not what we call hyacinth now.

Not

that hyacinths are not of respectable antiquity, quite as respectable

as iris. Very long ago they must have made the wreaths at festivals and

of bridesmaids in Greece, as they sometimes do to this day; very long

ago the Persian poet sang his fancy --

|

That every Hyacinth the Garden wears

Dropt in her lap from some once lovely head.

|

Though

in the latter case, when one thinks of the great hyacinths of the bulb

growers, one feels them to be a rather unwieldy decoration for the

"lovely head," and likely rather easily to be dislodged and fall to the

"garden's lap." But the original Hyacinthus orientalis,

parent of all our hyacinths, whether it came to us from Persia or from

the other side of the Himalayas, as Parkinson's sub-name zumbul

indi

rather suggests, was a very

different thing from the hyacinth of to-day. It was a very small, poor

thing, not so good as a poor specimen of the white Roman hyacinth that

blooms for us at Christmas. Even in Parkinson's time, when they had

been cultivated in Europe for more than fifty years, they were very far

from the present hyacinth, indeed nearer to the parent's standard.

"They have," he says, "flowers of a fair bluish purple colour, and all

standing many times on one side the stalk and many times on both." A

hyacinth now that is not flowered equally all round is an unheard-of

failure. And in number of florets, too, things are considerably

altered; a writer at the end of the eighteenth century speaks of a fine

hyacinth truss having from twenty to thirty bells; now the average is

from fifty to sixty, and one specimen of the variety Jacques,

bloomed in Haarlem, had one hundred and ten. All this, of course, is

the consequence of careful selection and cultivation, selection and

cultivation, and selection again, an art in which the Dutch growers

excel, and which is more successfully manifested in the development of

the hyacinth than in anything else.

Of all

bulbs, hyacinths perhaps are the most typically Dutch; tulips may have

the greater name, but other western nations have an interest in them

and a tradition of them. We find them in our old memoirs and tales; we

see them on the embroidered waistcoats of the beaux of Queen Anne's

court, and among the enamelled toys of the late days of the French

monarchy; they are figured in the prim paintings of our

great-grandmothers and on the cups of Dresden and Lowestoft china; they

even occur on the porcelain fragments that are discovered on the

far-off African coast, though probably there they are of Dutch or

Chino-Dutch origin. But a hyacinth, a big, full hyacinth, is

essentially and entirely Dutch; its very type and standard of beauty is

almost national, and nowhere else in the world can the bulb be produced

in perfection. In Ghent and near Berlin, in the sandy Spree plain, it

has been tried, but never with real success; the production of the

true, fine, and perfect hyacinth bulb belongs to the Dutch growers

alone.

The

bulb, even now after all these years of cultivation, is no trifle to

produce, no untended child of a summer's growth. It takes four years,

and care and understanding, to raise a marketable hyacinth bulb; four

years, or in some very propitious soils and circumstances, possibly

three. There are two methods open to the grower who is producing

hyacinths: either he slightly hollows the base of the bulb from which

he wants increase, or else he cross-cuts it in several directions with

cuts nearly half an inch deep. If he follows the latter course, he must

bury the bulb after cutting for a week, so that the cuts may open and

remain open. After that he will treat it as a hollowed bulb is treated,

that is, leave it alone in the dry warmth of the barn, and in time

there will appear between the layers innumerable young bulblets, of

sizes varying from a grain of rice to a pea. One may sometimes see on

the shelves of bulb barns the swollen and distorted parent bulbs, the

young bulbs distending all their coats, waiting in the warmth for the

time of planting. The parent, whether cut or hollowed, is planted whole

in this state, when a proportion of the young bulbs take individual

root and establish a separate existence. When in July the bulbs are

taken out of the ground the young ones are found to be nice little

bulbs of quite moderate proportions. Not yet, of course, of saleable

size nor of the blooming age; they want more years of planting and

lifting at the proper seasons before they are the substantial bulbs of

commerce. They flower before that time, sometimes in the first but more

often in the second year, but they have not come to perfection, and it

is not till they are four years old that there may be expected the

perfect, big, trussed flower.

Seeing

the labour in production one wonders, not that hyacinths are "so dear,"

but rather that they are so cheap; also one feels that they are hardly

treated with the respect they deserve in England. "They," so it is

often complained here, "do so little good the second year, and the

offset bulbs, when there are any, are so very poor." But why not? Why

should not the offsets be poor? If under the hands of those who give

time, and experience, and understanding, they are only good after so

much labour, why should they be good without any trouble or labour at

all? And for doing well a second year, a hyacinth is as other plants,

it has its time of maturity, its gradual approach to it, and its

decline: it takes four years to reach its finest under this treatment;

afterwards it usually declines from it. The rate and style of the

decline will vary, but it is not likely to be delayed by the treatment

of the English amateur or in the English flower-bed. "It is," so an old

grower once said, "as you may call the flower of one year, but what a

flower! It requires four years to make it, then there is the Flower;

after that -- it is nothing, usually I would not say thank you for it.

Ah, but when it is there, it is indeed a Flower! One can respect that!"

In

England hyacinths are not respected; the average English gardener now

wants something by the hundred for the border, he does not want

individuality. The old ladies who used to grow hyacinths in tall blue

and green glasses treated them with more respect. Hyacinth glasses are

not beautiful, yet one feels tenderly towards them for old sake's sake,

-- the memories of drowsy hours spent stumbling over Easy Reading

for the Young,

in a room where the glasses stood on the windowsill when spring had

dethroned the red sausage-shaped draught excluder, and the canary that

hung between chirped as he peeped first at the white flower in the blue

glass and then at the pink flower in the green, and possibly (at least

in the stumbling reader's mind) speculated as to whether the ghostly

roots to be seen through the glass were a rare and horrible specimen of

worm. Those hyacinths were appreciated, the first opening of the

flowers noted, the number of bells counted, the scent enjoyed with

neighbours not similarly blessed with bulbs. Now we do not grow

hyacinths in glasses. We, some people, grow them in pans, where they

look very like a small flower-bed moved into the house. Six or eight

"miniature hyacinths" (these are the immature offset bulbs of one or

two years' growth) crammed in together, where, one would think, they

must be very uncomfortable, though it does not prevent them from each

producing a truss of flowers, smaller and looser certainly than that of

a mature hyacinth, but giving satisfaction to the uninitiated. Some

people grow hyacinths singly in pots, and stand them in rows on

conservatory shelves or about their rooms, where they look well if the

rooms are solidly Victorian, or furnished with beautiful specimens of

cabinet-work in satinwood and tulipwood. Your hyacinth is no modern, no

ornament for the furniture and rooms of nouveaux arts

or culture, and it sorts very ill with half-toned ęsthetics

or the expensive pseudo-simple. Possibly that may account for its being

rather out of fashion in England just now, where few people have a

taste for the solidly Victorian, and fewer still the money for the old

satinwood of the eighteenth century, or the exquisite tulipwood of

France. Long ago it was different; seventeenth-century England admired

hyacinths greatly, obtaining, then as now, all the really good ones

from Holland, where already they were extensively cultivated. The price

fetched by choice bulbs then was high, though never quite equal to that

of tulips at the zenith of their fame. Report speaks of £200

being paid for a single hyacinth bulb in the middle of the seventeenth

century; but by the end of eighteenth £25 was thought

extravagant, even for a choice florist's variety. According to a writer

in 1796, the price of ordinary bulbs then varied from 3d. apiece to, in

rare cases, as much as £10. A fairly wide range, and one that

is not so very dissimilar from that of the present time, though it is

probable we now have a greater selection at 3d. and a smaller at

£10.

Hyacinths in the bulb gardens of Holland are planted in September in

very heavily manured ground. In the winter they have to be protected by

a thick covering of straw, more, indeed, than is given to any bulbs

except some of the lily family, usually from four to five inches in

thickness. This is taken off in spring, when the crowns appear; it is

essential that they should not be kept covered too long or too closely

in mild weather, or the prematurely developed shoots will be too tender

to stand the night frosts of early spring. Hyacinths are subject to

some few diseases; one of them necessitates the removal of a suspected

bulb from among its neighbours. Sometimes one may see a procession of

men going forth to the hyacinth fields, each armed with a long narrow

tool, in shape a little like the instrument used for cutting asparagus

in Belgium; and also, if the weather is sunny, carrying an umbrella, an

article much more used in Holland than in England. The procession, to

which the umbrellas give something of dignity if not solemnity, moves

slowly along a field, each man taking a row and examining the hyacinths

one by one for signs of the disease. With his umbrella he shields the

sun from his head and neck, the weather usually seems to be hot on

these occasions; with his tool he neatly and cleanly lifts the

suspected bulb from among its fellows.

Hyacinth flowers are cut off before their beauty is quite spent, so

that they shall not come to seed. Generally speaking, no bulb of any

sort is allowed to come to seed, unless of course that particular seed

is wanted for the raising of new varieties; to produce seed greatly

exhausts the bulb. Hyacinth flowers are cut close down to the leaves;

sometimes the cut blooms are scattered over the ground, where other

sorts of bulbs, as yet not showing shoots, are growing, this to prevent

the light sandy soil from being blown away, leaving the bulbs beneath

bare. Some few of the flowers are sold; some, I have heard it said, are

used for manure; but the great bulk of them seem just a waste product.

As yet nothing has been done with regard to extracting the scent from

them, though one would almost have thought it had been worth while. Of

course there would be difficulties in the way, the flowers have too

much moisture to allow of their being steam-distilled, like roses and

some other scent-providing flowers, and to pomade them, as violets are

pomaded, would be rather a costly process.

The hyacinth Hyacinthus orientalis,

though certainly the great man of the family, as parent of all that are

commonly called hyacinths, is, after all, only one of a group.

Parkinson gives forty-eight "iacinths," as he spells them. Some of

them, it is true, would seem to be only varieties of the same kind, and

some are things placed in other classes by modern florists. Still, even

without these, a good many remain, and some at least are grown in the

bulb gardens of Holland to-day. Grape hyacinths (Muscari,

because they were supposed to smell of musk) are of these. They are a

good deal grown in Holland, and are coming into much favour in England,

no one knows why. Hyacinthus candicans is

also grown in Holland. This, of course, is a newcomer from the Cape,

unknown to Parkinson; its tall stalks and far-scattered white bells

give it little resemblance in appearance to the rest of its relations.

The wood hyacinth, Nutans,

is also raised, but is usually to be found under the heading "Squills"

in a grower's list. Parkinson classes it with his iacinths, where one

would have thought it belonged, calling it Hyacinthus anglicus

belgiciis. He also classes with them what he calls Scilla alba

-- the

common squill of the Mediterranean -- the great and important squill of

old medicine, which, according to the herbalists, must have been good

for everything, epidemic, accidental, and chronic, from worms to

toothache, though most especially for consumptive diseases. "The

Apothecaries prepare thereof both Wine, Vinegar and Oxymel or Syrupe,

which is singular to exterminate and expectorate tough flegm, which is

a cause of much disquiet to the body, and an hinderer of concoction, or

digestion in the stomach, besides divers other wayes, wherein the

scales of the roots being dried, are used. And Galen hath sufficiently

explained the qualities and properties thereof, in his eight book of

Simples." Pliny, doubtless, explained something of the same, for he,

too, wrote of squills. So did that magnificent Dutchman, Clusius, who

reports that when, in the true spirit of inquiry, he was about to make

personal test of the Scilla rubra,

he was stopped by the Spaniards, who assured him it was a most strong

and potent poison. It is to be regretted that the Dutchmen of to-day do

not grow the

Scilla rubra, though perhaps it is not unreasonable, for, according

to all accounts, it was not much to look at.

Among

the flowers much more grown in Holland to-day than in former times iris

stands well first. The iris, of course, is an old flower, even though

it may have lost its first Greek name, and taken another after that

rather overworked personage, the cutter of life's threads and

rain-bringer, Juno's rainbow-winged messenger. Under various names the

iris, whether tuberous or bulbous, has figured a good deal in history

and legend. There has even been controversy about it, whether

Shakespeare meant an iris or a lily when he spoke of fleur-de-lys in

another than heraldic sense, and whether Chaucer did.

It is

quite clear the old masters of medicine understood "fiower-de-luce" as

iris, whether they spoke of "the bulbous blue kind" or the tuberous

"flaggy kind," the white flag of Florence, from which they, as we,

derived orris root, and the common yellow flag from which they derived

other things which we do not. Their descriptions and receipts for

mingling the extract with honey to mitigate the sharpness of its attack

upon the stomach(!) have come down to us to convince us that they knew

the iris; also that they, such of them as survived, were stouter men

inside than their decadent descendants.

Of late

years iris, dethroned from an honourable place in medicine, has come

much into fashion as a garden flower. Not without reason, many sorts

are easy for the amateur to cultivate, and all are very effective. The

variety among them is enormous; not only are there in the hands of

growers many comparatively new discoveries from North Africa, Central

Asia, Asia Minor, and South Europe, but the improving and altering of

all the families, new and old, has made the varieties wonderful both in

number and beauty now. Large quantities of iris are grown in Holland,

some of the rarer sorts and still more of the cheap and well-known

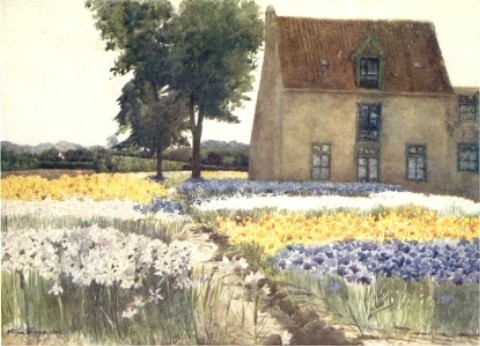

kinds. In June one may see fields of Spanish Iris (Iris xiphion),

exquisite, delicately-tinted flowers, quivering at the top of their

grey-green stalks. Blooming, as they do, when most of the other bulb

flowers are over, and when, in the early days of the industry, most of

the fields must have been rather bare, they have a separate and special

attraction. They are very nearly hardy bulbs, and withstand the

winter's cold with little protection. They are little trouble in the

growing, and are lifted at the end of July, when the greater number of

other bulbs are already harvested. They increase fairly well, and the

young ones have the further advantage of coming to maturity in a

comparatively short time. New varieties, as is almost invariably the

case with bulbs, are obtained from seed. One may often see small

patches of new sorts, of which the grower has hope, flowering beside

large quantities of the established kind, this for the sake of

comparison, and to determine if the new is really new, and has anything

worthy of preservation. The original bulb of Spain is said to have been

blue flowered, the yellow influence coming from Portugal; but the

crossing and blending of the two, whether started by art or nature, was

begun too far back to be recorded. It is impossible to trace the

history of many of the innumerable and beautiful shades and blends that

exist now.

Iris anglica is

another striking feature of the bulb gardens in early summer, coming

into flower just when the Spanish are over, and presenting a more

gorgeous and striking effect. It is a native of the Pyrenees, and no

relation in root or anything else to the tuberous-rooted flag-irises of

England. The Dutch growers had it, in the first instance, from English

sailors or merchants, and either mistook its place of origin or named

it after the nation from whom they received it. The flowers, with the

extraordinary variety they show, their somewhat stiff method of growth

and great development, are decidedly more typical of the nation of

gardeners than of the nation whose name they bear.

Among

the irises, both bulbous and tuberous, now grown in Holland I regret to

say I have not been able to identify the iris of Clusius -- "Clusius

his first great Flowerdeluce." "This Flowerdeluce hath divers long and

broad leaves, not stiff like all the others, but soft and greenish on

the upper side, and whitish underneath." The flower was "of a fair

blue, a pale sky colour in most," and showed in the six lower petals a

tendency to turn up at the edges, the three smaller and upper of these

parting at the lip and standing up "like unto two small ears." The

description of the flower reads a little like a Spanish Iris, and the

native place was clearly Spain; but the leaves sound quite different to

those of the Spanish as we know it, also the time of blooming is placed

too early. The flower is described as very sweet of scent, and "the

root is reasonable great." Doubtless, towards the close of the

sixteenth century it was to have been seen blooming in the famous

garden at Leyden; perhaps some descendants are still to be found in

that city, yearly honouring the great man who named them, and helped to

make the city famous. But in none of the gardens round Haarlem have I

seen it, and in no grower's catalogue does it figure, at all events

under its original name.

Irises, besides being among the latest of the

bulb flowers, are almost among the earliest. In early March one may see

Iris reticulata, Bakeriana, histroides,

and a few other delicate - looking specimens blooming in surroundings

which look singularly unsuitable to them. But these, as yet, are very

little grown, are somewhat costly, and still in appearance something

reminiscent of their Asiatic homes. None of them are recorded to be

natives of Europe, although I myself have seen irises surprisingly like

Iris reticulata,

which were found by their present owner growing wild in Spain. They

were, when I saw them, blooming under a north wall in a garden not far

from the Scottish border, this in a March blizzard, and they had done

so for some four years in succession. In colour, shape, and scent they

were exactly like reticulata, but whether or no they were truly

so I cannot say.

Among the more striking of the flowers to be

seen in Holland now, Iris susiana certainly deserves mention.

It is not a bulb iris but a spreading rhizome, in growth more like the

Iris germanica,

though in appearance quite unlike. It was introduced into Holland

somewhere about 1570, and has been grown there practically without

development or variation ever since, but the days of its market

popularity are comparatively recent. Twenty years ago it is doubtful if

there were fifty of the strange flowers (they look rather as if they

were made of Japanese newspaper) to be found outside the Dutch gardens.

Certainly in England they were then very little known. And yet

Parkinson, writing in 1629, gives them an important place among the

then known irises. There can be no doubt whatever that the Iris

susiana of

to-day is what he calls the Great Turkey Flowerdeluce, "the roots

whereof," he tells us, "have been sent out of Turkey divers times among

other things, and it would seem that they have had their original from

about Sufis, a chief city of Persia." His description of flower tallies

exactly, and he notes the peculiarity that the petals "being laid in

water will colour the water into a violet colour, but if a little

Allome be put therein, and then wrung or pressed, and the juice of

these leaves dryed in the shadow, they will give a colour almost as

deep as Indigo, and may be used for shadows in limning excellent well."

The flower of the Iris susiana,

if left in water or even allowed to rot in the ordinary way, produces a

very strongly-coloured juice of a bluish violet tint. There really is

no room to doubt that the two irises are the same, though how it

happened that the then and now valued flower went so out of English

cultivation, almost out of English knowledge, it is difficult to say.

One imagines that there came a time when no one appreciated its

"singularity and rarity " -- the only charms it has to offer -- and it

was allowed to die out. Without care, of course, it would not thrive or

increase. It seldom bears seeds in these colder countries, and the very

few that are occasionally borne never ripen. And it would hardly have

increased by spreading, -- as a rhizome if left undisturbed for long it

would always die in the centre of every clump it formed, only living at

the edges, and in an unpropitious climate and circumstances it would

speedily dwindle away. Anyhow, it would seem to have happened, the

Great Turkey Flowerdeluce left us, to return Iris susiana

many years later, when the tide of taste, which has changed many things

and relegated the formerly admired hyacinth to a secondary place, has

put all irises into fashion, and exalted this neglected flower to

favour and admiration. Such a fate has occurred before this to flowers

and books and men; to the books it matters little, they have time to

ripen; to the men -- post cineras gloria sera venit.

|