| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2008 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER VII BARON STIEGEL AND HIS GLASSWARE WHEN the assiduous historians of Pennsylvania have at length stripped bare of its mythical embellishments the story of "Baron Heinrich von Stiegel," there will still remain to us the biography of one of the most romantic characters that ever flourished on this side of the Atlantic. And there will also remain to those of us who care for such things a few pieces of the famous Stiegel glassware, among the early objects of fine domestic art manufactured in the Colonies. He was, indeed, not merely the picturesque, spectacular figure that legend has painted him, but an ironmaster, town builder, and glassmaker, and one of the most notable of pre-Revolutionary manufacturers in America. In

telling the story of Stiegel's life and career I shall endeavor to

confine myself to such facts as are now generally agreed upon by the

historians. His name was undoubtedly Heinrich Wilhelm Stiegel; that

is the way he signed the ship's roster when he came to this country.

Later, following the custom of his time, he varied it to Henry Wm.

Stiegel. He was born May 13, 1729, near Cologne, on the French side

of the Rhine (or, as the older tradition has it, near Mannheim,

Germany), the son of John Frederich and Dorothea Elizabeth Stiegel.

At the death of his father in 1741, he and his mother and his younger

brother Anthony gathered together their worldly goods and started for

the New world, where many of their neighbors had found liberty and

prosperity. On August 31, 1750, they arrived at Philadelphia on the

good ship Nancy.

The legend that Stiegel came with a patrimony of £40,000 has

been pretty well disproved; he probably came to these shores a

comparatively poor boy, seeking his for tune.

The mother and brother settled in Schaefferstown, Pennsylvania, where they lived and eventually died, but Heinrich traveled about the country looking for his chance. In those days there were thriving iron mines in Pennsylvania — the most productive in this country — and about them had sprung up forges and furnaces and prosperous ironmasters. One of these was Jacob Huber of Brickerville, Lancaster County. The Brickerville situation looked good to young Stiegel, and on November 7, 1752, he married Huber's daughter Elizabeth. Two daughters were born to them — Barbara and Elizabeth. In 1857, Stiegel had saved enough money to buy his father-in-law's furnace property, which he promptly tore down, erecting a new and larger one, which he named Elizabeth Furnace. On February 13, 1758, Stiegel's wife Elizabeth died and was buried in the Lutheran graveyard at Brickerville. A year and a half later he married Elizabeth Holtz of Philadelphia, who bore him one son, Jacob. He built a house near the Falls of the Schuylkill in Philadelphia, where they lived until 1765, when he made his chief residence at Elizabeth Furnace again. The

business of the Elizabeth Furnace prospered from the start, and he

began making an ovenless, pipeless, wood-burning iron stove which was

in tended to fit into the jamb of the kitchen fireplace. On these

first stoves appeared this inscription: Baron

Stiegel ist der Mann

Der die Ofen Geisen Kann. Which brings up the question of his alleged title of nobility. It was undoubtedly a nickname, but whether originally applied in honor or in jest, is a matter of conjecture. His extravagant habits of ostentation and the feudal elegance and lavishness of his manner of living certainly proved the aptness of the title, and it stuck. Perhaps that is all we need to know about it. At any rate, "Baron" Stiegel he will be to us so long as a piece of his glassware remains intact. Stiegel improved this stove, made a few open Franklins, and eventually perfected the ten-plate stove which served our ancestors for a hundred years. Few of these are now to be found intact, but Pennsylvania antiquarians have found it interesting to collect the iron plates. A stove-plate owned by Mr. George S. Danner bears a classic profile (the likeness of George III, perhaps) surrounded by a wreath. Below are Masonic emblems and above the inscription "Stiegel Elizabeth Furnace, 1769." By 1760, Stiegel had become one of the most prosperous ironmasters in Pennsylvania. Elizabeth Furnace was kept continuously busy and trade was growing. About seventy-five men were employed here. Near the furnace the Baron erected twenty-five tenant houses, several of which are still standing. The property included some 900 acres, much of it in timber, and a gang of men was employed to cut the wood and burn the charcoal that was used in smelting the ore. Stiegel owned also stores, a mill, and a malt house. A spacious house, substantially built of sandstone, which still stands near the site of the furnace, is said to be the mansion occupied by Stiegel during his monthly visits, while his main residence was in Philadelphia. At this house, as at Philadelphia, a corps of servants was maintained sufficient for any emergency. The Baron's proclivity toward a feudal establishment was beginning to assert itself. It was about this time, too, that Stiegel began seeking business expansion and new commercial interests. His first move in this direction was the purchase of a one-half interest in Charming Forge, near Womeldorf, Berks County, on Tulpehocken Creek. During

these years of business activity Stiegel had associated himself with

two shrewd brothers, Charles and Alexander Stedman, a merchant and a

lawyer of Philadelphia. In September, 1762, he formed a partnership

with them, paying £50 sterling for a one-third interest in

the

Stiegel Company and in a tract of 729 acres of land lying on the

north bank of Chiquesalunga or Chiques Creek, in Lancaster County.

Their plan was to develop a town here and make a fortune in real

estate.

Stiegel, before his departure for the New World, had received a first-class education. One of his many accomplishments was surveying, and he laid out the new town according to his own design and called it Manheim. Tradition asserts that it was originally a faithful replica of the German city of Mannheim. Here the company built and sold houses, subject to ground rental, and conducted a clever and successful boom. Within the area of the new town there were only two little log houses standing, but soon an orderly, attractive village replaced them. Early in 1763, Stiegel, who had become greatly interested in this venture, began the building of mansion number three at the corner of Market Square and East High Street. It was a square house, forty feet on each side, and was constructed of brick which were specially imported from England, and were hauled from Philadelphia in the Baron's wagons. The house was two years in building. When completed it was elaborately furnished. The great parlor was hung with tapestries of hunting scenes (part of which are preserved by the Pennsylvania Historical Society), doors and wainscoting were heavily paneled, and the mantels were adorned with blue Delft tiles. Stiegel was a religious man with a decided bent toward preaching. Half of the second floor in the Manheim house was built in the form of an arched chapel, with a pulpit and pews. Here the Baron was wont to gather his working people together, and in a pompous but solemn manner expound to them in the German tongue the doctrines of the Lutheran faith. Another unique feature of this house, illustrating his eccentricity perhaps as much as his taste for music, was a platform on the roof, surrounded by a balustrade, where a band of his employees discoursed music on all possible occasions on instruments of his providing. While the business at Elizabeth Furnace was prospering, with two hundred to three hundred workmen employed, progress at Manheim was a bit too slow to suit the enterprising Baron. Some industry was essential to insure the growth of the town, so Stiegel resolved to erect a glass factory. Glassmaking had been for centuries one of the industrial arts of. the region of Cologne, where Stiegel was born, and he may have received technical training in the trade, for subsequent events proved him to be no novice. He had, in fact, been manufacturing window glass and bottles in a small way at Brickerville since 1763, including clear glass and several greens. The new plant was built of imported brick and was completed some time after 1765. Tradition states that it was so large that a four-horse team could be driven through the doors, turned around, and driven out again, and that it was surmounted by a huge dome ninety feet high — dimensions that should not be accepted too readily. Stiegel made a trip or two to Europe and brought back with him skilled workmen from Germany and from Bristol. After some small manufacture of window glass and bottles, the major operations were commenced in 1768, and here the first American flint glassware was manufactured. By 1769 the glass factory was running at full capacity, with thirty-five glassblowers employed, and its products were sold in Philadelphia, Baltimore, New York, and Boston. The Baron's annual income from this industry alone was said to be £5,000, a tidy sum in those days. In August, 1769, the Stedman brothers sold out their interest in Manheim to Isaac Cox, and the following February Stiegel bought it for £107, 10s. He was now rated as one of the wealthiest men in Pennsylvania, and he certainly lived up to that reputation. He entertained lavishly at his various residences, and on one or two occasions George Washington is said to have been his guest. To give greater scope to his social activities he built, in 1769, a strange sort of tower on a hill near Schaefferstown, Lebanon County, some five miles north of Elizabeth Furnace. The hill is still known as Thurm Berg. The tower was a wooden structure, built of heavy timbers, in the form of a pyramid. Its dimensions are given as seventy-five feet high, fifty feet square at the base, and ten feet square at the top. Its exterior was painted red. On the ground floor were banquet halls, and above richly appointed guest chambers. This tower or "schloss" came in later years to be known as "Stiegel's folly," and fell into ruins soon after his death. During these years of his prosperity the Baron's tendency toward elaborate display became more and more marked. He was accustomed to drive in state from one of his residences to another in a coach drawn by four prancing steeds (coal black or milk white, according to varying traditions), guided by liveried postilions and accompanied by a pack of baying hounds. A cannon's roar announced his coming and departure at Thurm Berg, while at Manheim he was greeted by the shouts of the populace and the music of the band upon his housetop.

But with all this baronial splendor he never failed to act the part of the lord of bounty. He paid his workmen well and was greatly loved by them. He furnished them religious, musical, and intellectual instruction, and was perhaps the first American manufacturer to engage in what we know as welfare work. And, above all, he was a staunch supporter of his church. At one time he had a note of £100 against the Lutheran congregation at Schaefferstown which, in a moment of generosity, he cancelled. In 1770 he aided in the establishment of the Zion Church at Manheim, providing the lot for the sum of five shillings and the payment of "one red rose annually in the month of June forever, if the same shall be law fully demanded by the heirs, executors, or assigns." The legend states that the Baron brought a rosebush from England and planted it in the churchyard, and that this same bush is blooming still. However that may be, the "Feast of Roses" has been reëstablished in Manheim. In 1891 Dr. J. H. Sieling, one of Stiegel's most indefatigable historians, discovered among the dusty records of the church the original deed bearing the unique rental stipulation that had been forgotten for over a century. The debt, he found, had been paid in 1773 and 1774, and then, with the Baron's declining for tunes, had been neglected. In June, 1892, payment was resumed, and on the second Sunday of each succeeding June the pretty ceremony has been conducted by the Zion Lutheran Church at Manheim. A red rose from the churchyard is sent to one of the Baron's descendants, and piles of roses dropped within the chancel rail are sent to the hospitals. But evil days befell the princely Stiegel. His extravagant mode of living began to tell. The market for his glassware dwindled as hard times approached and he fell more or less a victim to scheming associates. The clouds of impending war shadowed all business and Stiegel found himself in a state of bankruptcy. He did his best to ward off the inevitable, even pawning his wife's gold watch in his extremity, and his poorer friends rallied to his support. But it was all in vain, and on October 15, 1774, he was cast into the debtor's prison. The hum of industry slackened at Manheim and Elizabeth, and the once opulent Baron found himself mortgaged and penniless. By a special act of the Assembly he was released from prison on Christmas Eve, 1774. Through the sale of the glass works and most of his real estate, and with the aid of his friends, he was able to raise sufficient funds to satisfy his creditors. But his days of opulence were ended and his costly equipage sold. Robert Coleman, who had gained control by lease of the plant at Brickerville, made him foreman of Elizabeth Furnace, and he took up his work again courageously. At first it was hard sledding, with all industry crippled by the outbreak of war, but in 1776 Stiegel procured orders for cannon, shot, and shells for the Continental troops. For a time this work kept the plant running night and day. During the winter at Valley Forge, Stiegel kept open the road of communication with Washington's army. During 1777 a band of Hessians captured at Trenton (zoo of them, it is said) were sent to Stiegel to enable him to dig a canal, a mile long, to increase his water power. Toward the end of 1778 the government orders ceased, and Stiegel again faced bankruptcy. He devoted the remnants of his fortune to the satisfying of his creditors, and then, abandoning all his dreams of commercial success, he established a modest home in the parsonage of the Lutheran Church at Brickerville, of which he had once been a munificent benefactor. Here, at the age of forty-eight, "a thin, bent old man," he settled down to a quiet life, gaining a scanty living by means of preaching, teaching school, giving music lessons, and surveying. In 1780 he moved back to Schaefferstown and in 1781 to Charming Forge, where he taught school and kept books for the factory. In 1782 his wife died while on a visit in Philadelphia, and on January 10, 1785, the day after the death of his brother Anthony at Schaefferstown, Heinrich Wilhelm Stiegel breathed his last and was presumably buried in an unmarked grave at Brickerville. Romantic as is the half-legendary story of Baron Stiegel's career, the thing which has kept his memory green outside his own section of the country is the well deserved fame of his glassware. Fortunately, the output of his factory was so great that a moderate amount of it is still in existence, not only in Pennsylvania but in Boston, New York, and else where, and it is coming to be more and more highly prized by collectors.

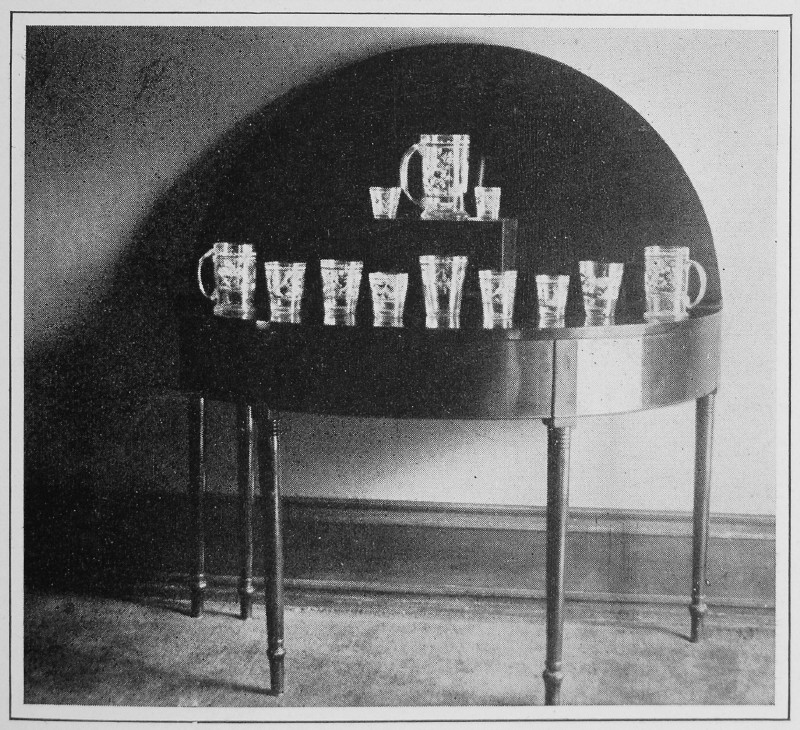

Glassmaking was one of the early industrial enterprises of the American Colonies, and Stiegel was by no means the first to engage in it. But to him remains the credit of having made the most notable and probably the first fine flint glass in America. His product included both utilitarian and art wares. For the table he made cream jugs, pitchers, sugar bowls, tumblers, wine glasses, large flip glasses, rummers with and without covers, salt cups, pepper cruets, dishes and plates, vinegar cruets, champagne glasses, mugs, finger bowls, other bowls, molasses jugs, caraffes, and egg glasses, all of better quality than any hitherto attempted in this country. These were made chiefly in four colors — white or clear glass, blue, purple, and green, beside the enameled ware. The blues predominate and show a wonderful depth, variety, and clearness of coloring. They range from a light sapphire to the deepest shades, and exhibit undertones of green or purple when held to the light. At least four shades of green are to be found and occasionally pieces were made in olive or amethyst. Much of the clear ware is beautifully engraved, and some of Stiegel's "cotton-stem" wine glasses rival the famous examples from Bristol. There were also made a few flint-glass articles flashed with a thin coating of white, and various two-colored pieces — blue and transparent, blue and opaque white, amethyst and transparent, etc. Stiegel also made window glass, sheet glass, bottles, flasks, chemists' tubes and retorts, measuring glasses, funnels, jars, jug stands, etc., as well as vases, scent bottles, and toys. The relief designs found in much of the Stiegel glass were made by blowing it in figured molds. Often the pattern was impressed in a small pattern mold and the article then blown in the open air by hand, giving such pieces a distended, asymmetrical appearance that is far from displeasing and that gives a wide variety of form among individual specimens. The commonest design is a diamond-shaped or diaper pattern, and many pieces are found with straight or twisted fluting. The quality of the glass is such as to render it remarkably vibrant. A bowl, struck sharply with the finger, will produce a clear, rich tone for fifteen or twenty seconds. Stiegel's enameled ware is particularly quaint and interesting. He was the first American manufacturer to attempt enameling on glass, and he imported skilled workmen for this purpose. Four patterns used to decorate tumblers and other pieces in bright colors are the most common, though these were varied considerably and others were occasionally used. Enameled mugs, steins, glasses, and cordial bottles were produced, as well as engraved bottles, tumblers, and flips. The most noteworthy collection of Stiegel glass is that of Mr. Frederick W. Hunter of New York, who has presented it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where it is now on exhibition. There are nearly three hundred pieces, altogether, including at least fifty of the remarkable blues. The Pennsylvania Museum also owns a good collection, as does Mrs. Albert K. Hostetter of Lancaster, Pennsylvania. The question of present values is always of prime interest to the collector. While it is impossible to be exact, it is safe to say that Stiegel glassware is worth from $5 for one of the smaller, plainer pieces to $20 or $25 for one of the larger, more elaborate examples, while $50 is not an unheard-of price for one of the finer flip glasses. Not long ago an authentic Stiegel tumbler or salt dish could be picked up for a dollar or two, but the interest in this ware suddenly increased less than five years ago, and market values advanced very sharply. A few collectors, indeed, pursued their quest with such zeal that as high as $100 was asked for a single piece. Prof. Edwin A. Barber of the Pennsylvania Museum writes : "Pieces which I could buy for $ 1.50 until a year or so ago are now quoted at $50 and up wards, which is ridiculous. I have, however, within the past few months, bought quite a number of pieces at reasonable prices, ranging from $5 to $20 each." There has been little or no attempt made thus far to fake Stiegel ware, though it has not been uncommon for similar products of a later period to be attributed to Stiegel by dealers and collectors. Stiegel glassware is distinguished by its brittleness and its bell-like resonance, by its light weight and thin texture, by its brilliant surface, by the beauty and uniformity of its colorings, by the quality of its relief patterns, by the decorative quaintness of its forms, and by its hand-made appearance. As objects of art Stiegel's best pieces are only beginning to be appreciated. Stiegel was an eccentric character undoubtedly, and he was an able man of business, who owed his downfall in part to an injudicious ambition and in part to his expensive tastes. But above all else he was an artist, a craftsman. True, he employed workmen of the highest skill and training, but they produced only so long as they felt the stimulus of his inspiring personality and enthusiastic direction. He alone was responsible for one of the most distinguished products of pre-Revolutionary America. |