| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2008 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER VIII THE VERSATILE PAUL REVERE SINCE

Fourth Reader days we have known of the midnight ride of Paul Revere.

As a patriot and a soldier he made a place for his name in American

Revolutionary history. But the collector and the student of early

American crafts finds him no less interesting as an engraver and as

the designer and maker of some of the most exquisite old silverware

that has come down to us from Revolutionary times.

In the recently awakened enthusiasm for Americana, old silver naturally has its place, and in that department of craftsmanship the interest is strongly focused upon Revere, partly because of his character and exploits, partly because of the exquisite quality of his workmanship, and partly because there is so much of it, comparatively speaking, to be found in private and public collections. But Revere's activities did not stop even here. He was a goldsmith and an engraver and a publisher of historical and political cartoons. He was a manufacturer of gunpowder, Church bells, and rolled copper. He even kept a hardware store in Boston, where he sold jewelry, picture frames, and false teeth. He was a high Mason and an industrial organizer, a Son of Liberty and a colonel in the army. Paul Revere was born in Boston January 1, 1735 (December 21, 1734, old style), and lived in Boston all his life. He was the third of twelve children and was named after his father, a Frenchman, who was christened Apollos Revoire, but changed his name to Paul Revere after coming to America. Paul Revere the elder was born at Riancaud, France, the son of Huguenot parents. In 1715, at the age of thirteen, he was sent to a brother in the Island of Guernsey to learn the trade of goldsmith. He came to America in 1723 and settled in Boston, being apprenticed here for a short time to John Cony. On June 19, 1729, he married Deborah Hichborn. He was successful in his calling, for a large part of American wealth in his day was centered in and about Boston and there was a growing demand for the silverware which it was part of the goldsmith's business to produce. He died in 1754 and his wife in 1777. Paul the son — the man known to history as Paul Revere — went to school in Boston to the famous Master Tileston at the North Grammar School. While still a youth he entered his father's shop to learn his trade, which included the designing as well as the making of silver pitchers, ewers, tankards, cans, teapots, spoons, porringers, etc. It also included chasing and engraving, and at this young Paul became an expert. On his father's death, when he was nineteen years old, he took charge of the shop. He joined a local artillery company, of which he became second lieutenant, and in 1756, when he was twenty-one years of age, he was sent on the expedition against the French at Crown Point. He served for six months at Fort William Henry on Lake George, but saw no action. Returning to Boston he devoted himself wholeheartedly to his trade and began turning out creditable silverware of his own designing. On August 17, 1757, he married Sarah Orne. She died May 3, 1773, after bearing eight children, and five months after her death Revere married Rachel Walker. The silver engraving interested Revere so much that he began experimenting on copper plate also, drawing some of his own subjects. By 1765 he had become known as a clever if somewhat crude caricaturist as well as a skilled engraver. Although we are at present interested in Paul Revere chiefly as a craftsman, no sketch of his life can well be presented without some account of his patriotic activities in the early days of our national struggle for independence. He belonged to that group of young and ardent patriots who kept affairs in Boston pretty well stirred up for a dozen years before the Revolution. He was a member of several patriotic Committees and on December 16, 1773, he took part in the famous Boston Tea Party. He was an accomplished horseman and often acted as messenger for the Committee of Safety. Twice in 1774 he rode to New York and Philadelphia to secure support and cooperation among the Colonies, once carrying with him the Suffolk Resolves — the forerunner of the Declaration of Independence. On December 13, 1774, he carried to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, the news of the embargo on munitions of war and the British plan of sending a strong garrison to Fort William and Mary at New Castle. As a result of his warning, the New Hampshire Sons of Liberty armed and surprised the fort on the night of December 14, capturing one hundred pounds of powder and fifteen cannon, which were later used with effect at Bunker Hill. This was the first organized, armed resistance to British rule. Most of us know of Revere's famous midnight ride from the poetic version, which is not entirely accurate. His own narrative is given in a letter to Jeremy Belknap, published in the Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

Revere was at this time a vigorous man of forty, an active member of the Sons of Liberty, and one of thirty volunteer night watchmen whose duty it was to keep in touch with the British movements in Boston, both military and political. They were well aware of the British plan to raid the stores at Con cord and Lexington and on April 18, 1775, reported that the time had arrived. There was also a price on the heads of Hancock and Adams, who were at Lexington, and on the night of the 18th Dr. Warren sent William Dawes and Paul Revere by different routes to warn them and the patriots at Concord. Dawes started first, but arrived later than Revere at the home of Rev. Mr. Clarke in Lexington, where Adams and Hancock were housed. It is hardly fair, however, that all the credit should be given to Revere. Revere set out from Charlestown at about eleven P. M., riding Deacon Larkin's horse. The incident of the lanterns in the church steeple was a matter of minor importance. Not far outside of Charlestown he was surprised and pursued by British horsemen, but escaped through Medford, arousing the minute-men along the way. He arrived at Lexington with his message about midnight. About an hour later Revere, with Dawes and Dr. Prescott, started out for Concord. They had not gone far before they were surrounded by British soldiers. Prescott promptly turned his horse, and leaping a stone wall, escaped, but Dawes and Revere were captured. They started back toward Boston, but before long the soldiers became alarmed by signs of gathering minute-men and relaxed their vigilance. Dawes started up his horse and dashed down the road, hotly pursued by three troopers. The story has it that as he approached a darkened farmhouse, he called loudly, "Hello, boys, I've got three of 'em," whereat his pursuers turned without further ado and fled. Revere was not so lucky. His horse was taken from him; but later, in the confusion, he man aged to slip away. On the following day, the 19th, occurred the skirmishes at Concord and Lexington and "the shot heard 'round the world." Most of the stores, thanks to the timely warning, had been safely hidden. Revolution having become more important than business to Revere, he arranged to have his affairs in Boston cared for while he moved to Charlestown and devoted himself largely to public activities. There were more important journeys on horseback to New York and Philadelphia and there was military service. In November, 1775, Revere was instructed, while in Philadelphia, to inspect the powder mill there, as Massachusetts badly needed one. The owner of the factory, jealous of his rights, would not give the emissary any information or permit him to make any drawings, though he allowed him to walk through the plant. Revere kept his eyes and ears open. He possessed a working knowledge of chemistry and of manufacturing processes in general, and when he re turned he was fully prepared to engage in the manufacture of gun powder for the Continental Army. The rebuilding of an old powder mill at Canton, Massachusetts, was begun in February, 1776, and was completed in May, and Revere took charge. He was able soon to supply tons of powder for the army. In 1776 he was also employed to repair the cannon left spiked at Castle William by the British on the evacuation of Boston. In July of that year he was made a major in a regiment organized for local defense, and in November became lieutenant-colonel of a regiment of state artillery, in which his son Paul, a lad of sixteen, became a lieutenant. The regiment saw some service in both Massachusetts and Rhode Island, but was stationed at Castle William the greater part of the time. Revere was in command of the fort during most of 1778 and 1779. In 1779 he took part in the ill-fated and mismanaged expedition to Maine, having charge of the artillery train. Commodore Saltonstall failed to cooperate, discipline among the state troops was weak, and the expedition was broken up by the British garrison at Penobscot. Very likely Revere became in subordinate under these trying conditions, but it is not to be believed that he was cowardly. However, serious charges were preferred against him and he was removed from his post at Castle William. He was arrested on September 6 and held a prisoner in his own home for two or three days, and then released.

Revere demanded a thorough investigation and would not remain satisfied with semi-acquittals, but it was not until February 19, 1782, that he at last obtained conclusive vindication from a competent court-marshal. His personal reputation seems not to have been seriously impaired, but his chances were spoiled for securing a coveted commission in the Continental Army. The year 1780 found Paul Revere back at his trade in Boston. During the war his business had naturally suffered, though he had profitably con ducted the powder mill at Canton and had been employed by the Government to oversee the casting of brass cannon. Also he had been engaged to supervise the making of our first national paper money. On May 10, 1775, the second Continental Congress in Philadelphia voted to authorize the issuance of two million Spanish dollars in bills of credit. John Adams and Benjamin Franklin were members of the committee which gave Revere the contract for engraving and printing. He constructed his own presses for this work. In December of the same year the Massachusetts Provincial Congress gave him a similar contract. Revere also found time to de sign and engrave a state seal for Massachusetts in 1775, and a second one, for the new State, in 1780. He was now forty-five years old, with a wife and eight children. One son, Paul, had learned the goldsmith's trade and another, Joseph Warren, was associated with him in various business enterprises. In spite of the fact that trade had been dull and a good deal of Revere's money had been tied up by the war, he was fairly well-to-do. For a few years Revere devoted most of his attention to the rehabilitation of his silverware business. In 1783 he opened a sort of jewelry store — called a "hardware shop" in those days — in Essex Street opposite the old Liberty Tree. Here he sold gold necklaces, bracelets, lockets, rings, and medals; dies, seals, etc.; silver pitchers, teapots, spoons, sugar baskets, spectacle bows, knee and shoe buckles, candle sticks, etc. Many of these things Revere made in his own shop. In spite of the hard times, a fairly good business with the wealthier families was developed. He also made frames for Copley's famous portraits. In 1789 he started an iron and brass foundry at the lower end of Foster Street, near Lynn Street, now the Causeway. In 1792 he took his son Joseph into this business. They began the casting of church bells and built up a considerable trade in this line throughout eastern Massachusetts. In 1794 they began the casting of brass cannon and the manufacture of metal fittings for ships. They were the first concern in this country to smelt copper ore and to refine and roll it, and were very successful in the handling of malleable copper. In 1798 they made the bolts, spikes, pumps, etc., for the United States frigate Constitution — "Old Ironsides." In 1801 they purchased the powder mill at Canton and commenced the erection of new buildings there. In 1802 they furnished the metal — over six thousand square feet of it — for recoppering the dome of the State House in Boston. They also made copper bottoms for seventy-four new gunboats for the Government. In October, 1804, the roof was blown off the factory in Boston and they moved the works to Can ton, retaining business headquarters in Boston. In 1809 they made the copper sheets for two boilers for the Livingston and Fulton steamboats on the Hudson River. Joseph Warren Revere continued this business at Canton after his father's death. Paul Revere was one of the best known members of the Masonic fraternity in America. He entered St. Andrew's Lodge in 1760, became Master in 1770, and was Grand Master of the Massachusetts Grand Lodge from 1795 to 1797. In this capacity he assisted Governor Samuel Adams in laying the corner stone of the State House, July 4, 1795. He made jewels and insignia for the Masons and engraved and printed elaborate membership certificates, etc. Revere was largely instrumental in founding the Massachusetts Charitable Mechanics' Association in 1795 and served as its president till 1799. He was also one of the incorporators of the Massachusetts Mutual Fire Insurance Company in 1798. He died at his home in Charter Street, Boston, May 10, 1818, at the age of eighty-three, and was laid to rest in the old, historic Granary Burial Ground. He had been successful in business and left a fortune of $31,000. He was distinctly a man of the times, and was greatly honored in his community. He was a big, virile man, active and in his youth fiery, but possessing also a strong vein of artistic feeling and creative impulse. Apart from his ability as a manufacturer, Paul Revere was a true craftsman, and his craftsmanship was threefold: he was a bell founder, an engraver, and a silversmith of great skill and talent. He learned the art of bell casting from Col. Aaron Hobart. Only a few large bells had been made in this country prior to 1770, including the historic Liberty Bell of Philadelphia. Revere had been a member of the guild in charge of the eight-bell chime in Christ Church and had long been interested in the subject. His first attempt was in recasting the old bell of the New Brick Church, afterward known as the Second Church of Boston, in 1792.

This early work was rough and unsatisfactory, but the subtleties of the art were soon mastered, and by 1803 the concern had cast sixty church bells. Their advertisement read as follows: "Paul Revere and Son at their Bell and Cannon Foundry at the North part of Boston Cast Bells and Brass Cannon of all Sizes and all kinds of Composition Work. Manufacture Sheets, Bolts, Spikes, Nails, &c., from Malleable Copper and Cold Rolled. N. B. Cash for Old Brass and Copper." In 1804 Revere sent his son, Joseph Warren, to England and the Continent, to study the art, and this expedition, together with their own experience, taught them how to perfect their product. Their masterpiece was the bell cast in 1816 for old King's Chapel to replace the one that was cracked in tolling the Peace of 1814. This bell was paid for at the rate of twenty-five cents per pound. Its strong, mellow reverberation is still to be heard from the massive tower. Between the years of 1792 and 1828, when Joseph Revere ceased casting bells, three hundred and ninety-eight of them were turned out from the factory, of which at least seventy-five are still in use. These were nearly all marked Paul Revere, Paul Revere & Son, or Revere & Co., with the date. Paul, Jr., the eldest son, continued in business with his father until 1801, when he started out for himself. His bells were usually marked Revere, with no date. As a copper-plate engraver, Revere was self-taught, and between 1766 and 1775 he turned out considerable work. In 1765 he engraved the scores for "A Collection of Psalm Tunes," published by Josiah Flagg and himself in Boston. This was followed by other music books, book illustrations, seals and book plates, paper money, portraits, and historical and political cartoons. As a caricaturist he gained a wide reputation, due as much to his cleverness in selecting his subjects, perhaps, as to his style of delineation. This style was crude, somewhere between Hogarth and the comic valentines of a decade ago; but it was not entirely without merit and it deserves our consideration because of its place in the history of the art of engraving as well as in the history of American independence. The most famous of the old prints is the Boston Massacre, published in 1770. With the inscriptions it measures eight and one-half by nine and three-fourths inches, and was somewhat crudely colored by hand.

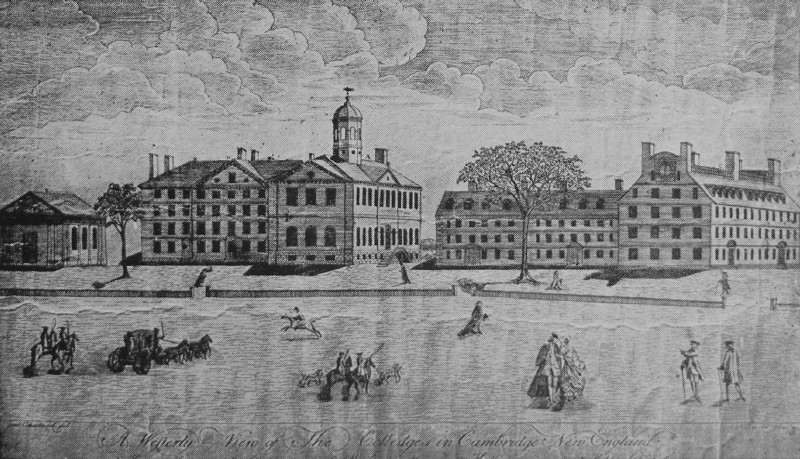

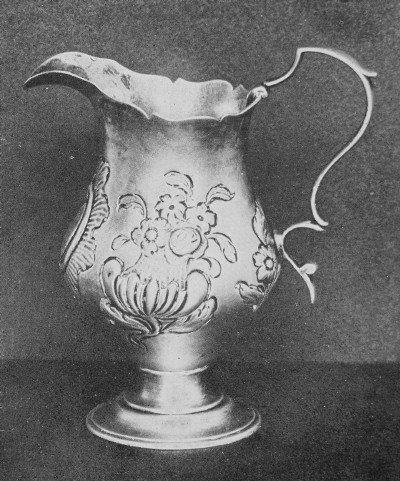

One of the rarest subjects and one of the most popular when published was the Harvard College group, drawn by Joseph Chadwick and engraved by Revere. Others of particular interest are the Repeal of the Stamp Act, published in 1766, a View of Boston Harbor, showing the location of the British ships of war, published in 1770; the Landing of the British, published in 1774. In all, Revere engraved three different views of Boston Harbor. He also engraved portraits and caricatures of prominent men. In 1775, when Revere was commissioned to make our first national paper money, copper plate was so scarce in this country that he took half of the Harvard College view and engraved the new bill on the back of that. This plate is preserved in the archives of the Commonwealth. Other special work by Paul Revere includes the seal of Phillips Andover Academy, still in use; the first state seal of Massachusetts, made in 1775, and the second state seal, 1780. He is also known to have made a number of bookplates, though only a few of these can now be identified. Among those which he signed were bookplates made for Gardiner Chandler, David Greene, Epes Sargent, William Wetmore, and himself. After 1775 the war took up most of Revere's attention, and after 1780 his manufacturing enter prises, so that practically all his engravings are pre- Revolutionary. The illustrations shown herewith are the famous Harvard College and Boston Massacre views, both the property of the Essex Institute, Salem, Massachusetts. The latter has been copied, both honestly and fraudulently, but only three or four authentic originals are known to be in existence, though there must be many others tucked away in storerooms and garrets. Harvard owns one of these originals, for which the university or its benefactor is said to have paid about $700. The interest in Revere silver is indicated by the fact that sixty-five pieces were shown at the splendid exhibition of American silverware at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts in 1906. Nearly every collection boasts its Revere pieces, and it is safe to say that the work of no other American silversmith has attracted so much attention or is valued more highly to-day. Paul Revere's silverware is distinguished by exquisite beauty of design and workmanship. Its great variety of form is shown in the accompanying illustrations. His style was based upon that of the English silversmiths of the eighteenth century, known as the Georgian style, but he added thereto the touch of his own master hand and a superb feeling for grace of line and proportion. His work compares favorably with that of the best English silver smiths of the period.

The decoration of Revere silver is of equal merit. The old Boston families, with their mingling of aristocratic and democratic tastes, were fond of crests, armorial designs, and cartouches enclosing initials, names, or inscriptions. This gave Revere a rare opportunity to exercise his talent for engraving and repoussé work. The fact that there were three silversmiths by the name of Paul Revere has occasioned some slight confusion, but by far the greatest quantity of ware was produced by the patriot. That attributed to his son is practically negligible. Some of the work of his father still exists and shows considerable merit, but it is exceedingly rare. There are no certain rules for distinguishing be tween the wares of father and son. Practically all the pieces bearing the signature P. REVERE were un questionably the work of the father, though this mark appears also on a few pieces that bear evidence of a later craftsmanship than his. It is possible that the patriot may have used his father's mark for a short time after the latter's death. The father's earliest mark consisted of the initials P R in a straight-topped shield, surmounted by a crown. Most of his existing work bears the mark P. REVERE in a narrow impressed rectangle. This mark the son changed slightly, using the name and narrow rectangle, but leaving off the initial of the first name, and substituting a small dot in its place. This mark appears on most of Paul Revere's silver, but occasionally he used a script monogram, PR, in an oval or rectangle, especially on his spoons. Paul Revere's most famous piece, and the premier piece of silverware in this country, is the large punch bowl made for the Sons of Liberty and now owned by Mr. Marsden J. Perry of Providence. There are in existence a few other pieces of historic significance, but for the most part Revere produced the type of domestic ware generally in fashion at that time. The early American silversmiths and their work will be discussed more fully in another chapter. It is impossible to place a correct money value on Revere silver. Perhaps $50 to $100 an ounce comes fairly near to an average estimate, but much of it is practically priceless. |