| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2021 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

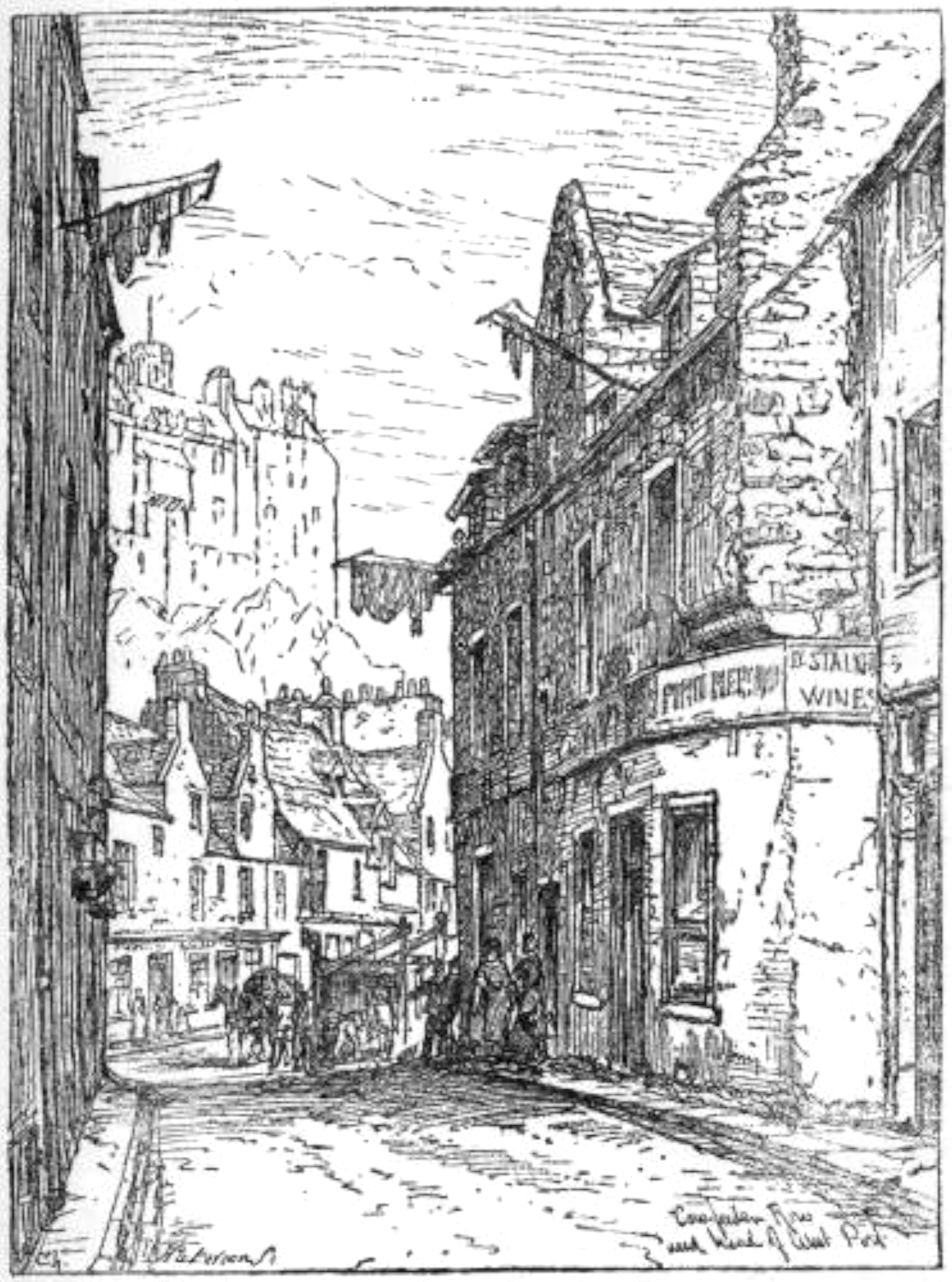

| CHAPTER II. OLD TOWN - THE LANDS. THE Old Town, it is pretended,

is the chief

characteristic, and, from a picturesque point of view, the liver-wing

of

Edinburgh. It is one of the most

common forms of depreciation to throw cold water on the whole by adroit

over-commendation of a part, since everything worth judging, whether it

be a

man, a work of art, or only a fine city, must be judged upon its merits

as a

whole. The Old Town depends for

much of its effect on the new quarters that lie around it, on the

sufficiency of

its situation, and on the hills that back it up.

If you were to set it somewhere else by itself, it would

look remarkably

like Stirling in a bolder and loftier edition.

The point is to see this embellished Stirling planted in

the midst of a

large, active, and fantastic modern city; for there the two re-act in a

picturesque sense, and the one is the making of the other. The Old Town occupies a sloping

ridge or tail of

diluvial matter, protected, in some subsidence of the waters, by the

Castle

cliffs which fortify it to the west. On

the one side of it and the other the new towns of the south and of the

north

occupy their lower, broader, and more gentle hill-tops.

Thus, the quarter of the Castle over-tops the whole city

and keeps an

open view to sea and land. It

dominates for miles on every side; and people on the decks of ships, or

ploughing in quiet country places over in Fife, can see the banner on

the Castle

battlements, and the smoke of the Old Town blowing abroad over the

subjacent

country. A city that is set upon a hill.

It was, I suppose, from this distant aspect that she got

her nickname of

Auld Reekie. Perhaps it was given

her by people who had never crossed her doors: day after day, from

their various

rustic Pisgahs, they had seen the pile of building on the hill-top, and

the long

plume of smoke over the plain; so it appeared to them; so it had

appeared to

their fathers tilling the same field; and as that was all they knew of

the

place, it could be all expressed in these two words.  Indeed, even on a nearer view,

the Old Town is

properly smoked; and though it is well washed with rain all the year

round, it

has a grim and sooty aspect among its younger suburbs.

It grew, under the law that regulates the growth of walled

cities in

precarious situations, not in extent, but in height and density.

Public buildings were forced, wherever there was room for

them, into the

midst of thoroughfares; thorough - fares were diminished into lanes;

houses

sprang up story after story, neighbour mounting upon neighbour's

shoulder, as in

some Black Hole of Calcutta, until the population slept fourteen or

fifteen deep

in a vertical direction. The

tallest of these lands, as

they are locally termed, have long since been burnt

out; but to this day it is not uncommon to see eight or ten windows at

a flight;

and the cliff of building which hangs imminent over Waverley Bridge

would still

put many natural precipices to shame. The

cellars are already high above the gazer's head, planted on the steep

hill-side;

as for the garret, all the furniture may be in the pawn-shop, but it

commands a

famous prospect to the Highland hills. The

poor man may roost up there in the centre of Edinburgh, and yet have a

peep of

the green country from his window; he shall see the quarters of the

well-to-do

fathoms underneath, with their broad squares and gardens; he shall have

nothing

overhead but a few spires, the stone top-gallants of the city; and

perhaps the

wind may reach him with a rustic pureness, and bring a smack of the sea

or of

flowering lilacs in the spring. It is almost the correct

literary sentiment to

deplore the revolutionary improvements of Mr. Chambers and his

following.

It is easy to be a conservator of the discomforts of

others; indeed, it

is only our good qualities we find it irksome to conserve.

Assuredly, in driving streets through the black labyrinth,

a few curious

old corners have been swept away, and some associations turned out of

house and

home. But what slices of sunlight,

what breaths of clean air, have been let in!

And what a picturesque world remains untouched!

You go under dark arches, and down dark stairs and alleys.

The way is so narrow that you can lay a hand on either

wall; so steep

that, in greasy winter weather, the pavement is almost as treacherous

as ice.

Washing dangles above washing from the windows; the houses

bulge outwards

upon flimsy brackets; you see a bit of sculpture in a dark corner; at

the top of

all, a gable and a few crowsteps are printed on the sky.

Here, you come into a court where the children are at play

and the grown

people sit upon their doorsteps, and perhaps a church spire shows

itself above

the roofs. Here, in the narrowest

of the entry, you find a great old mansion still erect, with some

insignia of

its former state - some scutcheon, some holy or courageous motto, on

the lintel.

The local antiquary points out where famous and well-born

people had

their lodging; and as you look up, out pops the head of a slatternly

woman from

the countess's window. The Bedouins

camp within Pharaoh's palace walls, and the old war-ship is given over

to the

rats. We are already a far way from

the days when powdered heads were plentiful in these alleys, with

jolly,

port-wine faces underneath. Even in

the chief thoroughfares Irish washings flutter at the windows, and the

pavements

are encumbered with loiterers.  These loiterers are a true

character of the scene.

Some shrewd Scotch workmen may have paused on their way to

a job,

debating Church affairs and politics with their tools upon their arm.

But the most part are of a different order - skulking

jail-birds;

unkempt, bare-foot children; big-mouthed, robust women, in a sort of

uniform of

striped flannel petticoat and short tartan shawl; among these, a few

surpervising constables and a dismal sprinkling of mutineers and broken

men from

higher ranks in society, with some mark of better days upon them, like

a brand.

In a place no larger than Edinburgh, and where the traffic

is mostly

centred in five or six chief streets, the same face comes often under

the notice

of an idle stroller. In fact, from this

point of view, Edinburgh is not so much a

small city as the largest of small towns. It

is scarce possible to avoid observing your neighbours; and I never yet

heard of

any one who tried. It has been my

fortune, in this anonymous accidental way, to watch more than one of

these

downward travellers for some stages on the road to ruin.

One man must have been upwards of sixty before I first

observed him, and

he made then a decent, personable figure in broad-cloth of the best.

For three years he kept falling -- grease coming and

buttons going from

the square-skirted coat, the face puffing and pimpling, the shoulders

growing

bowed, the hair falling scant and grey upon his head; and the last that

ever I

saw of him, he was standing at the mouth of an entry with several men

in

moleskin, three parts drunk, and his old black raiment daubed with mud. I fancy that I still can hear him laugh.

There was something heart-breaking in this gradual

declension at so

advanced an age; you would have thought a man of sixty out of the reach

of these

calamities; you would have thought that he was niched by that time into

a safe

place in life, whence he could pass quietly and honourably into the

grave. One of the earliest marks of

these degringolades is,

that the victim begins to disappear from the New Town thoroughfares,

and takes

to the High Street, like a wounded animal to the woods.

And such an one is the type of the quarter.

It also has fallen socially. A

scutcheon over the door somewhat jars in sentiment where there is a

washing at

every window. The old man, when I saw him

last, wore the coat in which he

had played the gentleman three years before; and that was just what

gave him so

pre-eminent an air of wretchedness.

One night I went along the

Cowgate after every one

was a-bed but the policeman, and stopped by hazard before a tall land.

The moon touched upon its chimneys, and shone blankly on

the upper

windows; there was no light anywhere in the great bulk of building; but

as I

stood there it seemed to me that I could hear quite a body of quiet

sounds from

the interior; doubtless there were many clocks ticking, and people

snoring on

their backs. And thus, as I

fancied, the dense life within made itself faintly audible in my ears,

family

after family contributing its quota to the general hum, and the whole

pile

beating in tune to its timepieces, like a great disordered heart.

Perhaps it was little more than a fancy altogether, but it

was strangely

impressive at the time, and gave me an imaginative measure of the

disproportion

between the quantity of living flesh and the trifling walls that

separated and

contained it. There was nothing fanciful, at least, but every circumstance of terror and reality, in the fall of the LAND in the High Street. The building had grown rotten to the core; the entry underneath had suddenly closed up so that the scavenger's barrow could not pass; cracks and reverberations sounded through the house at night; the inhabitants of the huge old human bee-hive discussed their peril when they encountered on the stair; some had even left their dwellings in a panic of fear, and returned to them again in a fit of economy or self-respect; when, in the black hours of a Sunday morning, the whole structure ran together with a hideous uproar and tumbled story upon story to the ground. The physical shock was felt far and near; and the moral shock travelled with the morning milkmaid into all the suburbs. The church-bells never sounded more dismally over Edinburgh than that grey forenoon. Death had made a brave harvest, and, like Samson, by pulling down one roof, destroyed many a home. None who saw it can have forgotten the aspect of the gable; here it was plastered, there papered, according to the rooms; here the kettle still stood on the hob, high overhead; and there a cheap picture of the Queen was pasted over the chimney. So, by this disaster, you had a glimpse into the life of thirty families, all suddenly cut off from the revolving years. The land had fallen; and with the land how much! Far in the country, people saw a gap in the city ranks, and the sun looked through between the chimneys in an unwonted place. And all over the world, in London, in Canada, in New Zealand, fancy what a multitude of people could exclaim with truth: 'The house that I was born in fell last night!' |

It is true that the over-population was at least as

dense in the epoch of lords and ladies, and that now-a-days some

customs which

made Edinburgh notorious of yore have been fortunately pretermitted.

It is true that the over-population was at least as

dense in the epoch of lords and ladies, and that now-a-days some

customs which

made Edinburgh notorious of yore have been fortunately pretermitted.