| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2013 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

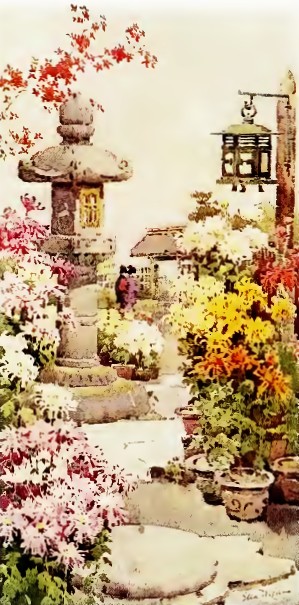

| CHAPTER

XV THE CHRYSANTHEMUM "SEE a kiri leaf fallen on the ground and know that autumn is with us" is a common saying in Japan. The leaves of the kiri (pawlonia) tree are so responsive to the spirit of autumn, which advances steadily till we see no garden flowers, no wild flowers, and have no longer the song of the insects, and one cannot fail to be impressed with some touch of sorrow; but the Japanese take sheer delight in the sadness of autumn, for soon the white frosts will be thick upon the ground and will turn the leaves of the maples on the mountain-side into a blaze of scarlet and gold, and then the kiku or chrysanthemum flowers will open. The chrysanthemum has often been called the national flower of Japan, a rank more properly belonging to the cherry blossom; the mistake arises from the fact that the sixteen-petalled chrysanthemum is the Imperial emblem. The Japanese give a poetical reason for the choice of this especial flower as the Emperor's crest: as in olden days the chrysanthemum used to be called Kukuri hana or "Binding Flower," because as the blossoms tie or gather themselves together at the top, so the Mikado binds himself round the hearts and souls of his people; and it is a coincidence that the present Emperor's birthday falls in the kiku month (November). For a thousand years the chrysanthemum was admired as a retired beauty by the garden fence and under a simple mode of culture; but it became the flower of the rich to a great extent under the Tokugawa feudal regime, and of late years the culture of kiku or chrysanthemum is the greatest luxury. It would probably surprise one to know how much Count Okuma and Count Sakai, the two best known chrysanthemum raisers in Japan, spend annually upon their plants; and many other people have found the reason of their poverty in kiku culture. Though one cannot but admire any advance in horticulture, carried to such an extent it seems to me merely a degeneration, and this "retired nobleman of flowers" (the Japanese call their kiku one of the sikunshi or four floral gentlemen, the other floral gentlemen being the plum, bamboo, and ran or orchid) will grow quite as well, and attain as great perfection, in some little humble dwelling which has only a miniature garden, provided the necessary time and care, not money, is given to the plants.  Chrysanthemums, Kyoto The chrysanthemum has always been much honoured by the Imperial Court, and even in the ninth century garden parties were held in the Palace gardens to do honour to the blossoms, even as in the present day a yearly chrysanthemum party is held in the Imperial grounds. In ancient days the guests sat drinking wine and composing odes to the blossoms, and the courtiers adorned their hair with kiku flowers, at these pastoral feasts. To-day these modern displays of chrysanthemum plants partake of our own conventional flower shows, the plants being arranged somewhat formally in long open rustic sheds; but the variety of colour, every imaginable shade being produced, and the profusion of form, also the immense size of some of the plants, one alone a few years ago bearing 1272 blooms, make a brilliant scene, different from any other flower show in the world; for where else would the plants have such a setting as in these beautiful Asakasa grounds, where the gorgeous colour of the maples rivals that of the chrysanthemums. From an artistic point of view there is nothing to admire in the great chrysanthemum show which opens yearly at Dangozaka in Tokyo, and one cannot but agree with the poet Hoichi Shonin, who says —

Lo! a waxwork chrysanthemum show!

However, one must admit the cleverness and some sort of art in these show pieces; and one cannot fail to be interested if only by watching the expectant faces of the thousands or tens of thousands of people who visit these different little shows. How the children's faces beam when they approach the place and see the thousands of flags and lanterns, gaily coloured curtains and stalls decorated with souvenirs in every conceivable form, of the day among the kiku flowers. The people are so enthusiastic over these puppet shows, which may be a scene from an old play, an act from history, or, most interesting of all, the newest occurrences of the day, all represented in chrysanthemums I In order to make the figures pot plants are used, not cut flowers, but splendid plants in full bloom, genuine plants, the roots of which are skilfully hidden or disguised. The colours of the flowers will be combined to represent the dresses, and indeed it is very interesting to see the figures being prepared in October when the plants are in bud, for each separate bud will be tied to the skeleton frame so that when the blossoms are open they form a compact mass of colour; and it is also very striking to notice the harmony of the colours, and then the bold lines made by a contrast of colour. A year or two ago there was nothing more popular than war scenes of the Russian and Japanese campaign. One scene which has remained green in the memory of many a Japanese was the representation of the blocking of the harbour at Port Arthur, with Captain Hiroze, that valiant officer, and his fellow keshitai (determined to die) as the characters. It was composed of two thousand chrysanthemum roots; upon a sea of the royal flowers, dark coloured at the heart and rising to sprays of snow white, to form the crests of the waves and tossing billows, rode the boat manned by the heroes. The second scene was a tribute to the enemy: it represented the stalwart white-bearded Russian Admiral Makaroff, who, standing on the bridge, sword in hand, went down with his ship — a veritable storm of white flowers, dashed with red, and here and there a few sailors groping blindly. There was yet another show which represented the night after the great battle of Lia Yang, when the spirits of the dead soldiers appeared, all flower-clad, with white swords in their hands, with which to salute the sleeping fighters. Every year the showmen find some new subject in order to keep up the people's interest. Besides these dramatic shows, there are splendid specimen plants; and what I always admired about the large plants in Japan was the perfect foliage, the rather dwarfed growth, and the way in which all the blossoms on the plant open together. There is a plant called "Good Luck" bearing a thousand flowers, all from a single root, which is a great favourite, and certainly it is nothing short of a horticultural wonder. Their fancy names seemed very poetical, and I cannot refrain from quoting a few, with their translation, in the words of a Japanese — "Look at the Princesses of the Blood in a long stately row, tall and graceful, their proud flowers resplendent and white as the driven snow; or here is Ake-no-sora, 'the Sky at Dawn,' with a pale pink flower the colour of cherry blossoms; or Asa hi no nami, 'Waves in the Morning Sun,' because it has a pale reddish blossom; also Yu hi kage, 'Shadows of the Evening Sun,' with dull red blooms; and finally the pure white 'Companions of the Moon,' Tsuki-no-tomo" There appeared to be over 150 of these poetical flowers. But do not imagine that it is only in the gardens of the rich or arranged as waxwork puppet shows that you will find chrysanthemums, for surely, if that were the case, little pleasure would be derived from their beloved kiku. It has been said of the Japanese, "It is not the plant he loves, but the effect that the plant enables him to attain." This may be true of plants in relation to the landscape garden, where everything must be according to the rubric or laws of gardening, but surely it is not true of chrysanthemum plants. Many an enthusiast have I known to whom his kiku was his most valued and cherished possession, and daily were the "Plants of the Four Seasons" (a fancy name for chrysanthemums on account of their period of growth extending through all the seasons) tended with loving hands. We are told of a great man in the days of the Min dynasty who, tired of struggling with the world and life, gave up his rank and retired to some forgotten spot, entirely in order to enjoy the sight of the chrysanthemum in his garden and a jug of wine; and the greatest delight of his life was to see the flowers bedewed in the morning light, and to exchange his poet's faith and love with this "nobleman of flowers." Perhaps in these days when the curse of modern civilisation is spreading throughout the land we shall not see many such enthusiasts as Yen Mei; but there are still many chrysanthemum lovers, many to whom the first week in November is the best week of the year. Just as the Japanese admire the flower for its noble bearing, so did I admire the bearing of their owners; however humble the dwelling, however small the collection, the proud possessor seemed always to be one of "Nature's noblemen"; never did I encounter such warm and true hospitality combined with dignity and grace as during the kiku month from my chrysanthemum hosts. One scene especially seems to have remained graven into my memory, in that land of surprises.  A Chrysanthemum Garden A friend offered to take me to see some especially fine chrysanthemums; their owner, he said, was celebrated for their culture; and he led me through the whole length and breadth of the fish market, I imagined only in order to make a short cut to our destination, but no! we stopped in front of a large fish-stall, and at the magic word kiku the owner's face beamed with delight, for surely here was a fellow-enthusiast, even though she is a "foreigner," come to admire his beloved flowers. He signed to me to thread my way past the somewhat unappetising-looking fish, and, as though at the touch of a fairy wand, the scene changed. A paper shutter slid back and the beauty revealed beyond surpassed anything that mortal could imagine — little corners and flashes of loveliness in all directions. At the very entrance were grouped a few splendid plants, each bloom perfection itself, and then with cries of "Irasshai irasshai" (Welcome, welcome) and the regulation greeting of "Please come in, my house is yours" from every side, I entered, crossing the cool matting, past a tiny court filled with the treasured plants and adorned with a hanging iron lantern which filled my soul with envy, through the spotless rooms with the alcove and the regulation kakemono and the tokonoma on which stood a flower arrangement of Baka sakura ("Fool Cherry," because it has come into flower at the wrong season), to the court beyond, where stood the famous collection. The whole scene diffused a feeling of perfect contentment as I sat upon the regulation fukusa in the place of honour, the place corresponding to the "Stone of Contemplation" of every Japanese garden, the one spot from which the whole effect is seen to best advantage. The plants were grouped in front of the family shrine, and to protect them from the autumn storms a light roofing of paper and bamboo had been erected; the little garden contained a few stepping-stones, a bronze water basin, a few lanterns, and to screen off any possible view of anything suggestive of fish was a delicate bamboo screen-fence. The blossoms seemed to represent every colour, shape, and size that it was possible for a chrysanthemum to assume, all perfectly grown plants. Some varieties were quite new to me — tall, slender-growing stems crowned with little fluffy blossoms not suggesting the usual form of a chrysanthemum; another, which when fully developed would form a complete pyramid of closely packed petals of a dark crimson hue, was awarded the place of honour, as there were only two other plants of the same kind in all Japan. I noticed some plants bearing a label which differed from any others, and then I was told that each year a special messenger is sent by the Emperor to choose a few plants from this humble fishmonger's garden to be added to the Imperial collection. The labelled plants formed this year's offering to his Mikado, and small wonder they were the pride of the house; and I too was impressed by the feeling that in the floral kingdom, as in a Higher Kingdom, all men are equal, as the kiku flowers had grown as well, if not better, in this lowly dwelling as in the Emperor's vast domains. I cannot recall any incident during all my stay in Japan which gave me more pleasure than my visit to this humble home, and as I left, laden with little kiku cakes and with the prescribed compliments, obeisances, and sincere admiring exclamations over the flowers, I had every intention of availing myself of the repeated invitations to "Please come again." The plants one day were in their full glory, the great heads of perfect blossom had only just attained perfection, when I was told that this was to be their last day of life, on the morrow every plant would be cut down. I exclaimed in horror at this apparent slaughter of the innocents in their prime of life, but it was explained to me that the sacrifice was necessary in order to secure the cuttings for the next year's plants. I could not help thinking that if I had nursed the cherished plants all through the year, shading them from the intense heat of summer on the house-top, never allowing them to know the want of water, I could not have spared the blossoms in their prime even for the sake of the next year's growth. Many another peaceful little garden I can recall where I was welcomed with all the grace and hospitality suggestive of Old Japan, and to this day apparently inseparable from the lovers of chrysanthemums. Two neighbours vied with each other in kiku culture, their houses only separated by a few yards. In one, an old man, whose bearing and manners suggested the Daimyo of olden days, sat as if he too, tired of the world, had retired with the sole companionship of his plants. Very lovely was his tiny garden, with the plants just grouped in front of the two rooms which constituted his entire house, and there he sat in quiet contemplation, or bowing low to meet some new-comer who had come to admire his flowers, and all seemed welcome, strangers and friends alike, as long as they loved the blossoms. Here might be seen the great sun-like Nihon lchi ("First in Japan"), white and yellow; and there is Haruna Kasumi, like its name, suggesting spring haze, or Natsu gumo ("Summer Clouds"); but with all this infinite variety I noticed that, like in China, where by "the yellow flower" is meant the chrysanthemum of that country, so here in Japan, the yellow blossoms seemed the most prized, though the pure white is a close rival for popularity, their blooms thick with the morning dew reminding us of the fairy who lived only by sipping the dews upon the kiku flowers. How beautiful, too, are these white blossoms in death when the frost has made their petals turn slowly to a crimson colour.  Chrysanthemums Across the road I found another little sanctuary, another home for the flowers. Here a tiny tea-room was the point of vantage, and from there I gazed, sipping tea from the daintiest of tiny cups. What an ideal place to sit and meditate and wonder over the goodness of things 1 Below was the rocky bed of a stream, but it was a dry river-bed, only white pebbles represented the stream, and on the banks were grouped the plants, forming a sheet of colour — great gorgeous blossoms, not of such mammoth and unnatural proportions as our show blooms, but every kind were here, single, loose, or double; stiff, flopping, or erect; borne in a veritable harvest. Yet another humble dwelling I remember where the plants were grouped with consummate art. In every garden there should be a keynote in the scheme, and here the keynote was the view of Hieisan: framed between the blossoms, which grew in a great foaming mass, rose the great mountain, as though it were the guardian of the garden. The plants had brilliantly rewarded a loyal devotion, and as I turned away I realised the manner in which Japanese love their flowers. As I sat admiring their gardens, my Mends told me many fairy stories and legends connected with the kiku. Perhaps one of the prettiest is called "The Chrysanthemum Promise." Samon Hase, a scholar and samurai, offered a night's lodging to a gentleman from the western country, and his guest suddenly fell ill. Samon promised the sick man to give him every help: "Be easy in your thought. Above all, be not discouraged!" The sick man was Soemon Akana, who had been with a friend on a mission which failed, and his friend was killed, and he was on his way home when he fell ill. Samon and Soemon quickly became friends, and finally they promised to be as brothers to each other. The latter stayed until he grew well; and then he said he must go back to his native province of Izume, but promised that he would return again and stay with Samon for the rest of his days. He said firmly that the day of the chrysanthemum feast (ninth of September in the old calendar) would be the day of his return. September came, and on the ninth Samon rose early to make preparations for his returning brother. The sun began slowly to set, but Soemon did not come. Samon thought he would retire to bed, but as he looked out once more into the night he noticed that the moon was hiding behind the hill, and he saw a curious black shadow coming towards him with the wind. It was Soemon Akana. Samon made his brother sit by the chrysanthemum vase in the place of honour, and Akana said, "I have no word to express my thanks for your kindness. But pray listen, and do not doubt me: I am not a living person but only a shadow"; and he told how he had been put in prison, but finding no other means of escape he killed himself. "As I was told," he said, "that a spirit could travel a thousand miles a day, so I killed myself; and rode on the wind to see you on this day of my chrysanthemum promise." I felt if this legend were taught in the schools of to-day a moral might be pointed with advantage on the subject of keeping appointments and promises, which is not a strong point with the modern Japanese. There is another pretty story of two brothers who had always lived together in the north of Japan. The time came for them to separate, and when the younger one was about to start on his journey south, they wept bitterly, and said that each would keep the half of a chrysanthemum plant in memory of the other, and thereby recall the happy days they had spent together. The brothers afterwards planted the halves in two gardens, one in the north, the other in the south; but the blossoms, it is said, kept the original shape of the half of a chrysanthemum for ever. The chrysanthemum is so associated with the story of O Kiku, the little maid of Himeji, in the province of Banshu, that I feel I cannot do better than tell it in the words of Lafcadio Hearn —

Himeji contains the ruins of a great castle of thirty turrets; and a daimyo used to dwell therein, whose revenue was one hundred and fifty-six thousand koku of rice. Now, in the house of one of that daimyo's chief retainers was a maid-servant of good family, whose name was O Kiku; and the Kiku signifies a chrysanthemum flower. Many precious things were entrusted to her charge, and among other things ten costly dishes of gold. One of these was suddenly missed and could not be found; and the girl, being responsible therefor, and knowing not otherwise how to prove her innocence, drowned herself in a well. But ever thereafter her ghost, returning nightly, could be heard counting the dishes slowly, with sobs: Ichi-mai, Ni-mai, San-mai, Yo-mai, Go-mai, Roku-mai, Shichi-mai, Hachi-mai, Ku-mai. Then there would be heard a despairing cry and a loud burst of weeping, and again the girl's voice counting the dishes plaintively: "One, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine." Her spirit passed into the body of a strange little insect, whose head faintly resembled that of a ghost with long dishevelled hair; and it is called O kiku-mushi, or the "fly of O Kiku"; and it is found, they say, nowhere save in Himeji. A famous play was written about 0 Kiku, which is still acted in all the popular theatres, entitled Banshu-O-Kiku-no-Sara-Ya-shiki, or "The Manor of the Dish of O Kiku of Banshu."

But there are people who say that Banshu is Bancho, an ancient quarter of Tokyo (Yedo). The people of Himeji claim, however, that part of their city now called Go-Ken-Yashiki is the site of the ancient manor of the story. And it is deemed unlucky to cultivate chrysanthemums in Go-Ken-Yashiki. |