| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2013 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER

XVI THE MAPLE LEAVES

THE Japanese quite rightly give the name of Ko haru or Little Spring to the Indian summer, Keats's season of mists and mellow fruitfulness; for indeed those beautiful weeks in November are incomparable, the heavy damp heat of the summer has lifted, the sky is clear and blue, the atmosphere is light, and the freshness of spring seems to have returned to revive the dying year. They say, "Here is the right end, since we had a right start" These fortunate people who rejoice in the beauty of spring beginning with the plum blossoms born out of the frost, now have the autumn with the momiji or maple leaves to complete the floral season, and the red leaves will be the beauty of the maturing year. Autumn weaves her red and gold brocade and spreads it on mountain and tree, the whole country being alight with the scarlet and gold of the momiji; for not only the maples are called momiji, but any tree whose leaves turn red in their last moment of life. Throughout the land there are favourite places where the holiday-maker holds his maple-viewing feast. The trees at Nikko are probably the first to turn, and by the middle of October this little mountain village will be visited by a throng of sight-seers, all bent on viewing the red leaves; and here truly not only the maples, but every tree seems to wear its mantle of autumn brocade, making a splendid contrast to the bronze green of the cryptomerias. The first touch of frost will have made the trees blush, so the  The Scarlet Maple Japanese say — it being a favourite expression of theirs, when a blush of modesty spreads over a girl's cheeks, to say that "she scatters red leaves on her face," — and then will come the first light fall of snow or a rude wind storm and scatter all the silent beauty of the valley. If you would continue your maple feast, you must go farther south, say to Oji near Tokyo, where you will find a whole glen filled with nothing but maples. No other momiji will dispute their fiery splendour; and there, in a little rustic tea-shed, you can sit and gaze at the gorgeous scene below, and wonder whether it is more beautiful to see the leaves like lace-work against the sky, or to look down on the great spreading branches shading the stream below. Here and there will be a tree that does not deserve the name of momiji, for it has no red leaves. Possibly it is a descendant of the celebrated maple-tree of the Shomeiji temple at Mutsuura, which turned a glorious colour when summer had scarcely waned, in order to earn the praise of the poet Chunagon Tamesuke, who went to seek the beauties of the early maple. The tree being fully satisfied with the admiration of the poet, remained green for ever after; for did not the poet say —

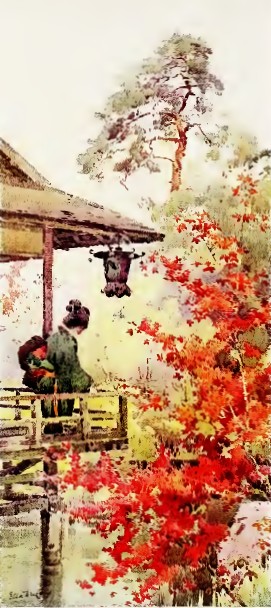

This one garden maple-tree Showing Autumn before the mountain trees!" It is always said that the poetical spirit of Tamesuke moved the responsive heart of the maple-tree. Kyoto, the old capital, with its history of centuries, is celebrated for the numerous places renowned for maple-viewing. All through the early part of November there is feasting, combined possibly with mushroom-gathering, a favourite pastime connected with the viewing of the momiji. Near by there is Tsuten Bridge, where the sound of revelry will greet you as you approach, and there will be the inevitable little tea-stalls, decorated with curtains printed with a few flaunting maple leaves, lanterns ornamented with the same red leaves, and branches of the trees adorned with red and yellow paper leaves; bearing a streamer with the name of the place, or possibly a diminutive paper lantern, to carry away as a souvenir of the day's feasting. If you want a wider field and more extensive view, remember Takao is waiting in all its glory to greet you; there a great stream of colour winds away down the valley following the course of the little mountain torrent. You must rise early for maple-viewing, to see the trees while the sun is on them; when the sun goes it seems as though he takes half the beauty of the momiji away with him, only to return it on the morrow, it is true, if the clear bright days will last through the short season of the momiji. Any night a cruel frost may come, and next day the ground will be covered with a scarlet carpet, reminding one of the story of that great lover of maple leaves, the Emperor Takakura-no-In. He planted the maple-trees at Kita-no-Jin, and called the spot Momiji Yama or Maple-leaf Hill. His great delight was to see the red leaves which carpet the ground with autumn glory. One morning his unpoetical gardeners swept away the fallen leaves, and the officers of the Imperial household were awestruck, as they were sure the Emperor would visit the hill to see the red leaves which might have been cast down by the night wind. He went to the hill, and the officers appealed to him to have pity on the gardeners' ignorance. "It reminds me," said the Emperor, "of the famous verse by Ri Tai Haku which runs —

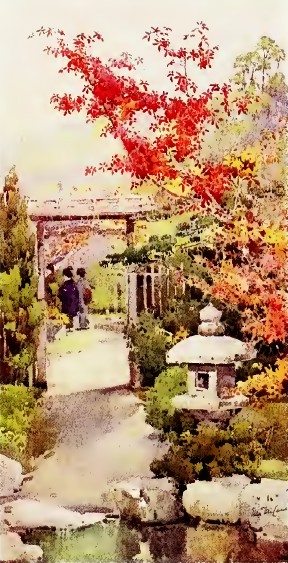

"We will burn up the maple leaves." Such is the song of autumn: "how lovely the gardeners' hearts in gathering the leaves to warm their hearts and wine." So not only was the stupidity of the gardeners excused, but happily their action was approved. Had the gardeners such poetical hearts? I doubt it; rather, how forgiving was the heart of the Emperor. Arashi Yama must not be omitted from the maple-viewing feast. Here the beauties of Nature summon us twice a year — in spring to visit the cherry blossoms, in  Viewing the Maples autumn to view the momiji. At the latter season the trees are dressed in red, and the water will be red too, so thickly is it carpeted with the fallen leaves. If one takes a boat to cross the water one feels ashamed to see the rent it makes in the "autumn brocade," for the boat will cut a track right through the thin carpet of leaves, of which the poet says —

Over the mountain river, Is nothing but the maple leaves Not run down the stream.

At Mino there are nothing but maples as far as the eye can reach, on and on down the glen, an incredible blaze of colour. But it was not in these great masses, though no one can deny their gorgeous splendour, that the maple gave me most pleasure; it was rather in some quiet garden away from the sound of feasting that a few trees of the choicer and therefore even more brilliant coloured varieties afforded me most enjoyment. I am thinking now of a warm November day when I had been bidden to take part in a tea ceremony, with all its quaint ceremonial and code of rules. Sitting in the little simple open tea-room — for does not the law forbid any elaborate decoration in the room set apart for tea ceremonies, and must not the room always be open on one, if not two sides? — while trying to conform to the rigid etiquette of this pretty ceremony of drinking tea in a preternaturally slow manner, when it was no longer my turn to admire in regulation words one of the articles used in the tea-making, my eye wandered to the scene outside, where, hanging over a miniature cascade, adding effect to the tiny rushing torrent, stood the maple-trees, surely the brightest I had ever seen. Maple-trees are most necessary for the Japanese landscape garden, especially when, as is usually the case, the style of the garden is to reproduce natural scenery. The Japanese have a saying that autumn comes from the west, therefore the maple-tree, the true representative of autumn, should be planted on a hill towards the west, so that it will welcome autumn promptly, and also in order that the reddening leaves may receive additional splendour from the setting sun. Here, in the glow of the western sun, it seemed incredible that the little trees were only clad in leaves, not in flowers, for their colour was as bright as, if not brighter than, the brilliant azaleas which had been the pride of the garden in the flower month of May. The nursery gardens are gay with splendid specimens of the much-prized dwarf maple-trees, and every lover of these little trees will have a few plants of momiji in his collection. Some there may be which had, as it were, been born with scarlet leaves — in spring the leaves having opened a fiery red, their colour waning as the year wanes; others which had only green leaves in the spring will, like true momiji, have got more and more fiery in colour until the shadow of death comes over them. Innumerable varieties there appeared to be, distinguished by the shape of their leaves and the tone of their colour. The changing life of the maple, Miss Scidmore tells us, has been made use of by "the Japanese coquette, who sends her lover a leaf or branch of maple to signify that, like it, her love has changed." If you call a Japanese baby and it opens its tiny hand, they call it "a hand of maple leaf." Throughout November the whole land is redolent of momiji; not only will the red leaves on the trees greet you at every turn, but you will be offered tea out of little cups painted with just one red leaf, the cakes represent maple leaves, the Geishas will all have soft crępe kimonos decked with a pattern of the flaunting leaves, or their stiff silk obis will represent Nature's "autumn brocade." In the theatres the romantic play called Momiji gari, or Maple-leaf Viewing, is played, the stage being gorgeously decorated with maple trees. Possibly because it is the last flower-viewing feast of the year, the momiji-viewing is almost the most popular, and when the last leaf falls the feasters will have to rest until the plum blossoms are opening, as Nature even in this land of flowers must take her winter's rest. |