| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2008 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

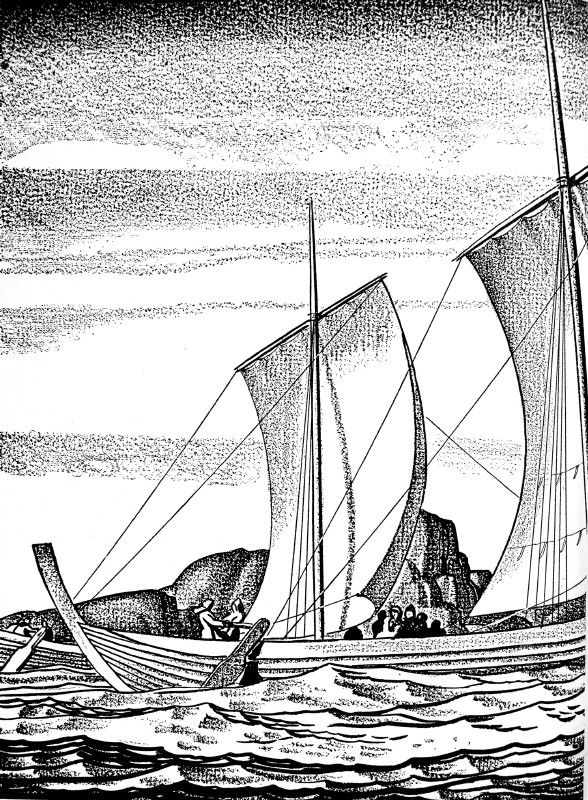

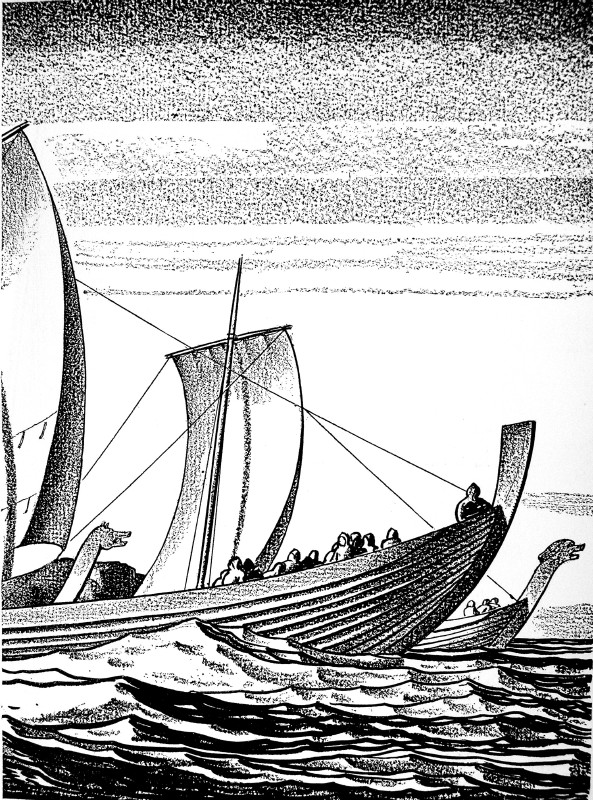

| CHAPTER III WHEN spring was come, the brothers-in-law, Thorgrim and Thorkel,

made ready the ship which the Eastmen had owned. These Norsemen had

been great men of tumult in Norway and had had some uneasiness there. The

kinsmen now took their ship and fared abroad. And that summer also went Vestan and Gisli away to Skeljavik in Steingrimsfirth, and both of them put to sea.   Onund from Medaldale was left in charge of the home of Thorkel

and Gisli; and Saka-Stein with Thordis, of that at Sabol. Now when these things are told, Harold Greyfell was ruling

over Norway. Thorgrim and Thorkel came in their ship to land far to the

north in Norway, and chanced upon the king suddenly and went before him and

spoke him well. The king took to them, and they were made his men and got much

money and honor. Gisli and Vestan were out at sea more than a hundred days,

and about the beginning of winter put into. Hordaland [in western Norway] at

night in a driving snowstorm and raging gale. They had their ship broken into

pieces but saved their goods and men. There was a man named Skegg-Bjalfi. He owned a trading-ship and

intended to go southward to Denmark. Gisli and Vestan wanted to buy half

interest in his ship. He said he had learned that they were good, fearless men,

so that he gave them the half, and they paid over forthwith more than full

worth. Then they all went south to Denmark to the tradingstead called Vebjorg,

[in Jutland] and they stayed there the winter with a man by the name of Sigrad.

They were there, all three together, Vestan, Gisli, and Bjalfi, and good

friendship held among them all, and giving of gifts. But early in the spring Bjalfi

set sail for Iceland. There was a man named Sigurd, partner of Vestan and a

Norwegian by birth. He was at that time west of there in England. He sent word

to Vestan, saying he wished to break off dealings with him and thought he

needed not Vestan's share any longer. Then Vestan begged leave that he might go

to meet him. "This shalt thou promise me," said Gisli, "that

thou wilt never fare away from Iceland, if I now give thee leave and if thou

comest back safe from thy journey." Vestan said yes to it. And one morning Gisli rode up and

went to a smith. He was of all men the handiest and most skilled in all

things. He made a coin which weighed not less than an ounce and welded it

together. There were twenty nails in it, ten in each half, and it seemed as if

it were all of one piece when it was laid together, but it could be taken apart

in two pieces. And of it it is said that Gisli took the coin apart and gave one

half of it to Vestan and told him to keep it as a token--"and we shall

send it from one to the other only in case the life of one of us is at stake.

And so my mind tells me that we might have need to send them between us, though

we ourselves do not meet again." Then Vestan went westward to England, but Gisli and Bjalfi set

sail for Norway13 and afterwards in the summer went out to Iceland.

They were well off in money and good name and ended well their fellowship. Bjalfi

there bought Gisli's half of the ship, and thereafter Gisli fared westward to Dyrafirth

in a merchant ship, he and twelve other men. Now Thorgrim and Thorkel made ready their ship m another

place and came back to Iceland at the mouth of the Hawkdale river in Dyrafirth on

the same day as that on which Gisli had sailed in on the merchant ship. Soon

they ran upon each other, and a joyful meeting it was. Then fared each of them

to his own home. They, too, were well off in goods, Thorgrim and Thorkel. Thorkel was very vain and did no work about their farmstead,

but Gisli toiled night and day on end. One fine day there was when Gisli had

all the men at work making hay, all except Thorkel. He was, alone of all the

men, at home in the house and had lain down in the hall after his day-meal. This

room was a hundred fathoms long and ten wide. Outside and to the south under

the hall stood the women's bower of Aud and Asgerd. They at the time were

seated there, sewing. And when Thorkel awoke, he went to the women's quarters

because he heard voices coming therefrom, and he lay down there near the bower. Soon Asgerd began to speak: "Help me in this, Aud, to

cut a shirt for Thorkel, my husband." "That I cannot do better than thou," said Aud, "and

thou wouldst not ask it of me, if thou hadst a shirt to cut for Vestan, my

brother." "That is something by itself," said Asgerd, "and

so it is like to seem to me for some time." "Long have I known," answered Aud, "how

things stood, but let us speak no more." "That seems to me not a thing to be held worthy of

blame, though Vestan does appear to me to be a good man. It was told me that thou

and Thorgrim met very often, too, before thou wast given to Gisli." "Nothing

wrong followed that," said Aud, "because behind Gisli's back I had

no man to whom any blame attaches. And now we shall break off this talk."

But Thorkel heard every word that the two women had spoken and when they had

finished, he began to speak: "Great things these I've been hearing!

Deadly things! High talk! I hear in them man's death, one or more!" After

that he went in. Then Aud spoke: "Oft but little good comes from the

chatter of women, and it might be that it will result here in the worst. Let us

now take counsel." "Thought I have of a plan of my own which he will

listen to," said Asgerd. "What is that?" asked Aud. "To put my arms around Thorkel's neck when we two go to

bed; then will he forgive me this and say those things were lies." "Thou wilt scarcely get off with that alone," said

Aud. "What wilt thou do to help?" asked Asgerd. "Tell

Gisli, my husband, everything I find hard to talk about or to settle." In the evening Gisli came home from his work. It usually

happened that Thorkel thanked his brother for the work, but this time he kept

silent and spoke not a word. So Gisli asked whether he was ill. "I have no sickness," answered Thorkel, "though

it is worse than that." "Have I done aught in this," asked Gisli, "wherefore

thou art displeased with me?" "That is not the case," said Thorkel, "and thou

wilt find out about it, though it may be rather late." Now they went, each

of them, his own way, and nothing more was said at the time. Thorkel took

little meat that evening and went, first of the men, to rest. When he had gone

to his bed, Asgerd came there and lifted up the bedclothes, thinking to lie

down, but Thorkel began speaking: "Not at all do I intend that thou

shouldst lie here the night, nor any more hereafter." "Why hast thou changed so quickly? Or what brings thee to

this?" asked Asgerd. Thorkel made answer: "We know, the both of us, the

reason, though I have long been secret about it, and if I speak more freely, thy

praise will not be the greater." She replied, "Thou wilt have to decide in thy afterthoughts

about that. I shall not long have words with thee about the bed. Two choices hast

thou to make. One is that thou take me to thyself and act as if nothing had

been. Otherwise shall I name witnesses forthwith and declare myself parted

from thee; and my father I shall have claim what was given by thee at our

marriage and also what I brought to thee from my home. And this choice will

mean that thou shalt never lack room in thy bed thereafter because of me." Thorkel was silent and after a time spoke out his thoughts:

"This have I decided, that thou mightest do which of the two thou likest; but

I shall not keep thee from the bed at night." She soon made known which seemed to her the better and went

straightway to her bed. They had not both lain together long ere they settled

all between them, as if nothing had been amiss. Aud, too, went to bed with Gisli and told him of her talk

with Asgerd and begged his forgiveness and asked him to think of some good

counsel if there were any he might sow abroad. "No thought am I right here aware of," said he, "such as might be of help, but I shall not hold thee to blame, for someone

worthy is always chosen to speak the words of fate, and that will come about

which is destined to be." Now the season of winter passed, and it was drawing near to

the time of removing days [at the end of May]. Then Thorkel drew Gisli his brother

into talk and spoke to him. "Thus is it decided, brother," said he,

"that to me has come somewhat of a change in condition and mind; wherefore

it has come to pass that I desire that we should share our goods, for I will

try joint-housekeeping with Thorgrim, my brother-in-law." Answered Gisli: "Better it is to see brothers' lands

and goods together. Certain I am, it is to my liking that things be at rest and

that we do not share what is ours." "It may no longer follow," said Thorkel, "that

we have the home together. And because in this there has been great unfairness

to thee, in that thou hast always had the work and toil on the farm, nothing

shall I take away with me which has thrived because of thee." "Take to thyself no blame for that," said Gisli, "as

long as I speak not of it. Now have we two, each of us, found that we have been

good friends, and are so no more." Thorkel answered: "There is nothing behind what has

been spoken, but I shall of a certainty divide the goods. And for the reason,

that I was the one to ask the sharing, thou shalt have the farmstead and what

our father left us, and I shall take what can be moved away." "If nothing else can be but that we make the dividing,

then do thou the one or the other, whichsoever thou wilt, for I care not which

I do, the sharing or the choosing." The end was that Gisli agreed to share and Thorkel chose

the chattels, and Gisli had the land. Then they shared those who could not keep

themselves. There were two young people, a boy and a girl. The boy was named Geirmund and the girl, Gudrid. They were children of Ingiald, their kinsman. Gudnd stayed with Gisli and Geirmund with Thorkel. Thorkel went to Thorgrim, his brother-in-law, and made his home with him. Gisli stayed behind on the farm, and nothing was missed that might make the housekeeping and the home worse than before. NOTES: 13. Bjalfi is mentioned above as having set out for Iceland:

a slip, evidently for his intentions. |