| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2018 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Little Journeys To the Homes of Great Scientists Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

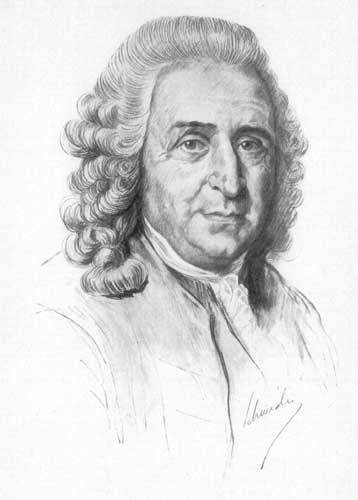

LINNĈUS

When a man of

genius is in full

swing, never contradict him, set him straight or try to reason with

him. Give

him a free field. A listener is sure to get a greater quantity of good,

no

matter how mixed, than if the man is thwarted. Let Pegasus bolt he

will bring

you up in a place you know nothing about! Linnĉus LINNĈUS  ut of the mist

and fog of time, the name of

Aristotle looms up large. It was more than twenty-three hundred years

ago that

Aristotle lived. He might have lived yesterday, so distinctively modern

was he

in his method and manner of thought. Aristotle was the world's first

scientist.

He sought to sift the false from the true to arrange, classify and

systematize. ut of the mist

and fog of time, the name of

Aristotle looms up large. It was more than twenty-three hundred years

ago that

Aristotle lived. He might have lived yesterday, so distinctively modern

was he

in his method and manner of thought. Aristotle was the world's first

scientist.

He sought to sift the false from the true to arrange, classify and

systematize.Aristotle

instituted the first

zoological garden that history mentions, barring that of Noah. He

formed the

first herbarium, and made a geological collection that prophesied for

Hugh

Miller the testimony of the rocks. Very much of our scientific

terminology goes

back to Aristotle. Aristotle was

born in the mountains

of Macedonia. His father was a doctor and belonged to the retinue of

King

Amyntas. The King had a son named Philip, who was about the same age as

Aristotle. Some years

later, Philip had a

son named Alexander, who was somewhat unruly, and Philip sent a

Macedonian cry

over to Aristotle, and Aristotle harkened to the call for help and went

over

and took charge of the education of Alexander. The science of

medicine in

Aristotle's boyhood was the science of simples. In surgery the world

has

progressed, but in medicine, doctors have progressed most, by

consigning to the

grave, that tells no tales, the deadly materia medica. In Aristotle's

childhood, when

his father was both guide and physician to the king, on hunting trips

through

the mountains, the doctor taught the boys to recognize sarsaparilla,

stramonium, hemlock, hellebore, sassafras and mandrake. Then Aristotle

made a

list of all the plants he knew and wrote down the supposed properties

of each. Before

Aristotle was half-grown,

both his father and mother died, and he was cared for by a Mr. and Mrs.

Proxenus. This worthy couple would never have been known to the world

were it

not for the fact that they ministered to this orphan boy. Long years

afterward

he wrote a poem to their memory, and paid them such a tender, human

compliment

that their names have been woven into the very fabric of letters. "They

loved each other, and still had love enough left for me," he says. And

we

can only guess whether this man and his wife with hearts illumined by

divine

passion, the only thing that yet gladdens the world, ever imagined that

they

were supplying an atmosphere in which would bud and blossom one of the

greatest

intellects the world has ever known. It was through

the help of

Proxenus that Aristotle was enabled to go to Athens and attend the

School of

Oratory, of which Plato was dean. The fine,

receptive spirit of

this slender youth evidently brought out from Plato's heart the best

that was

packed away there. Aristotle was

soon the star

scholar. To get much out of school you have to take much with you when

you go

there. In one particular, especially, Aristotle, the country boy from

Macedonia, brought much to Plato and this was the scientific spirit.

Plato's

bent was philosophy, poetry, rhetoric he was an artist in expression. "Know thyself,"

said

Socrates, the teacher of Plato. "Be thyself,"

said

Plato. "Know the world of Nature, of which you are a part," said

Aristotle; "and you will be yourself and know yourself without thought

or

effort. The things you see, you are." Twenty-three

years Aristotle and

Plato were together, and when they separated it was on the relative

value of

science and poetry. "Science is vital," said Aristotle; "but

poetry and rhetoric are incidental." It was a little like the classic

argument still carried on in all publishing-houses, as to which is the

greater:

the man who writes the text or the man who illustrates it. One is almost

tempted to think

that Plato's finest product was Aristotle, just as Sir Humphry Davy's

greatest

discovery was Michael Faraday. One fine, earnest, receptive pupil is

about all

any teacher should expect in a lifetime, but Plato had at least two,

Aristotle

and Theophrastus. And Theophrastus dated his birth from the day he met

Aristotle. Theo-Phrastus

means God's speech,

or one who speaks divinely. The boy's real name was Ferguson. But the

name

given by Aristotle, who always had a passion for naming things, stuck,

and the

world knows this superbly great man as Theophrastus. Botany dates

from Theophrastus.

And Theophrastus it was who wrote that greatest of acknowledgments,

when, in

dedicating one of his books, he expressed his indebtedness in these

words:

"To Aristotle, the inspirer of all I am or hope to be."  fter

Theophrastus' death the science of botany slept for three hundred

years. During this interval was played in Palestine that immortal drama

which

so profoundly influenced the world. Twenty-three years after the birth

of

Christ, Pliny, the Naturalist, was born. fter

Theophrastus' death the science of botany slept for three hundred

years. During this interval was played in Palestine that immortal drama

which

so profoundly influenced the world. Twenty-three years after the birth

of

Christ, Pliny, the Naturalist, was born.He was the

uncle of his nephew,

and it is probable that the younger man would have been swallowed in

oblivion,

just as the body of the older one was covered by the eager ashes of

Vesuvius,

were it not for the fact that Pliny the Elder had made the name

deathless. Pliny the

Younger was about such

a man as Richard Le Gallienne; Pliny the Elder was like Thomas A.

Edison. At twenty-two,

Pliny the Elder

was a Captain in the Roman Army doing service in Germany. Here he made

memoranda of the trees, shrubs and flowers he saw, and compared them

with

similar objects he knew at home. "Animal and vegetable life change as

you

go North and South; from this I assume that life is largely a matter of

temperature and moisture." Thus wrote this barbaric Roman soldier, who

thereby proved he was not so much of a barbarian after all. When he was

twenty-five, his command was transferred to Africa, and here, in the

moments

stolen from sleep, he wrote a work in three volumes on education,

entitled,

"Studiosus." In writing the

book he got an

education to find out about a thing, write a book on it. Pliny

returned to

Rome and began the practise of law, and developed into a special

pleader of

marked power. He still held his commission in the army, and was sent on

various

diplomatic errands to Spain, Africa, Germany, Gaul and Greece. If you

want

things done, call on a busy man: the man of leisure has no spare time. Pliny's

jottings on natural

history very soon resolved themselves into the most ambitious plan,

which up to

that time had not been attempted by man he would write out and sum up

all

human knowledge. The next man to

try the same

thing was Alexander von Humboldt. We now have Pliny's "Natural

History" in thirty-seven volumes. His other forty volumes are lost. The

first volume of the "Natural History," which was written last, gives a

list of the authors consulted. Aristotle and Theophrastus take the

places of

honor, and then follow a score of names of men whose works have

perished and

whom we know mostly through what Pliny says about them. So not only

does Pliny

write science as he saw it, but introduces us into a select circle of

authors

whom otherwise we would not know. We have the world of Nature, but we

would not

have this world of thinkers, were it not for Pliny. Pliny even

quotes Sappho, who

loved and sung, and whose poems reached us only through scattered

quotations,

as if Emerson's works should perish and we would revive him through a

file of

"The Philistine" magazine. Pliny and Paul were contemporaries. Pliny

lived at Rome when Paul lived there in his own hired house, but Pliny

never

mentioned him, and probably never heard of him. One man was

interested in this

world, the other in the next. Pliny begins

his great work with

a plagiarism on Lyman Abbott, "There is but one God." The idea that

there were many arose out of the thought that because there were many

things,

there must be special gods to look after them: gods of the harvest,

gods of the

household, gods of the rain, etc. There is but

one God, says Pliny,

and this God manifests Himself in Nature. Nature and Nature's work are

one.

This world and all other worlds we see or can think of are parts of

Nature. If

there are other Universes, they are natural; that is to say, a part of

Nature.

God rules them all according to laws which He Himself can not violate.

It is

vain to supplicate Him, and absurd to worship Him, for to do these

things is to

degrade Him with the thought that He is like us. The assumption that

God is

very much like us is not complimentary to God. God can not do

an unnatural or a

supernatural thing. He can not kill Himself. He can not make the

greater less

than the less. He can not make twice ten anything else than twenty. He can not make

a stick that has

but one end. He can not make the past, future. He can not make one who

has

lived never to have lived. He can not make the mortal, immortal; nor

the

immortal, mortal. He can change the form of things, but He can not

abolish a

thing. Pliny preaches the Unity of the Universe and his religion is the

religion of Humanity. Pliny says: "We can not

injure God, but

we can injure man. And as man is part of Nature or God, the only way to

serve

God is to benefit man. If we love God, the way to reveal that love is

in our

conduct toward our fellows." Pliny was close

upon the Law of

the Correlation of Forces, and he almost got a glimpse of the Law of

Attraction

or Gravitation. He sensed these things, but could not prove them. Pliny

touched

life at an immense number of points. What he saw, he knew, but when he

took

things on the word of Marco Polo and Sir John Mandeville (for these

gentlemen

adventurers have always lived), he fell into curious errors. For

instance, he

tells of horses in Africa that have wings, and when hard pressed, fly

like

birds; of ostriches that give milk, and of elephants that live on land

or sea

equally well; of mines where gold is found in solid masses and the

natives dig

into it for diamonds. But outside of

these little

lapses, Pliny writes sanely and well. Book Two treats of the crust of

the

earth, of earthquakes, meteors, volcanoes (these had a strange

fascination for

him), islands and upheavals. Books Three and

Four relate of

geography and give amusing information about the shape of the

continents and

the form of the earth. Then comes a book on man, his evolution and

physical

qualities, with a history of the races. Next is a book

on Zoology, with a

resume of all that was written by Aristotle, and with many

corroborations of

Thompson-Seton and Rudyard Kipling. Facts from the "Jungle Book" are

here recited at length. Book Nine is on marine life sponges, shells

and coral

insects. Book Ten treats of birds, and carries the subject further than

it had

ever been taken before, even if it does at times contradict John

Burroughs.

Book Eleven is on insects, bugs and beetles, and tells, among other

things, of

bats that make fires in caves to keep themselves warm. Book Twelve is

on trees,

their varieties, height, age, growth, qualities and distribution. Book

Thirteen

treats of fruits, juices, gums, wax, saps and perfumes. Book Fourteen

is on

grapes and the making of wine, with a description of the process and

the

various kinds of wine, their effects on the human system, with a goodly

temperance lesson backed up by incidents and examples. Book Fifteen

treats of

pomegranates, apples, plums, peaches, figs and various other luscious

fruits,

and shows much intimate and valuable knowledge. And so the list runs

down

through, treating at great length of bees, fishes, woods, iron, lead,

copper,

gold, marble, fluids, gases, rivers, swamps, seas, and a thousand and

one

things that were familiar to this marvelous man. But of all subjects,

Pliny

shows a much greater love for botany than for anything else. Plants,

flowers,

vines, trees and mosses interest him always, and he breaks off other

subjects

to tell of some flower that he has just discovered. Pliny had

command of the Roman

fleet that was anchored in the bay off Pompeii, when that city was

destroyed in

the year Seventy-nine. Bulwer-Lytton tells the story, with probably a

close

regard for the facts. The sailors, obeying Pliny's orders, did their

utmost to

save human life, and rescued hundreds. Pliny himself made various trips

in a

small boat from the ship to the beach. He was safely on board the

flag-ship,

and orders had been given to weigh anchor, when the commander decided

to make one

more visit to the perishing city to see if he could not rescue a few

more, and

also to get a closer view of Nature in a tantrum. He rowed away

into the fog. The

sailors waited for their beloved commander, but waited in vain. He had

ventured

too close to the flowing lava, and was suffocated by the fumes, a

victim to his

love for humanity and his desire for knowledge. So died Pliny the

Elder, aged

but fifty-six years.  ll children are

zoologists, but a botanist appears upon the earth only

at rare intervals. ll children are

zoologists, but a botanist appears upon the earth only

at rare intervals.A Botanist is

born not made.

From the time of Pliny, botany performed the Rip Van Winkle act until

John Ray,

the son of a blacksmith, appeared upon the scene in England. In the

meantime,

Leonardo had classified the rocks, recorded the birds, counted the

animals and

written a book of three thousand pages on the horse. Leonardo dissected

many

plants, but later fell back upon the rose for decorative purposes. John Ray was

born in Sixteen

Hundred Twenty-eight near Braintree in Essex. Now, as to genius no

blacksmith-shop is safe from it. We know where to find ginseng, but

genius is

the secret of God. A blacksmith's

helper by day,

this aproned lad with sooty face dreamed dreams. Evenings he studied

Greek with

the village parson. They read Aristotle and Theophrastus. Have a care

there, you Macedonian

miscreant, dead two thousand years, you are turning this boy's head! John Ray would

be a botanist as

great as Aristotle, and he would speak divinely, just as did

Theophrastus. It

is all a matter of desire! Young Ray became a Minor Fellow of Trinity

College,

Cambridge; then a Major Fellow; then he took the Master's degree; next

he

became lecturer on Greek; and insisted that Aristotle was the greatest

man the

world had ever seen, except none, and the Dean raised an eyebrow. The professor

of mathematics

resigned and Ray took his place; next he became Junior Dean, and then

College

Steward; and according to the custom of the times he used to preach in

the

chapel. One of his sermons was from the text, "Consider the lilies of

the

field." Another sermon that brought him more notoriety than fame was on

the subject, "God in Creation," wherein he argued that to find God we

should look for Him more in the world of Nature and not so much in

books. Matters were

getting strained.

Ray was asked to subscribe to the Act of Uniformity, which was a

promise that

he would never preach anything that was not prescribed by the Church.

Ray

demurred, and begged that he be allowed to go free and preach anything

he

thought was truth new truth might come to him! This shows the

absurdity of

Ray. He was asked to reconsider or resign. He resigned resigned the

year that

Sir Isaac Newton entered. Fortunately,

one particular pupil

followed him, not that he loved college less, but that he loved Ray

more. This

pupil was Francis Willughby. Through the bounty of this pupil we get

the

scientist otherwise, Ray would surely have been starved into

subjection.

Willughby took Ray to the home of his parents, who were rich people. Ray undertook

the education of

young Willughby, very much as Aristotle took charge of Alexander.

Willughby and

Ray traveled, studied, observed and wrote. They went to Spain, took

trips to

France, Italy and Switzerland, and journeyed to Scotland. Willughby

devoted his

life to Ornithology and Ichthyology and won a deathless place in

science. Ray specialized

on botany, and

did a work in classification never done before. He made a catalog of

the flora

of England that wrung even from Cambridge a compliment they offered

him the

degree of LL.D. Ray quietly declined it, saying he was only a simple

countryman, and honors or titles would be a disadvantage, tending to

separate

him from the plain people with whom he worked. However, the Royal

Society

elected him a member, and he accepted the honor, that he might put the

results

of his work on record. His paper on the circulation of sap in trees was

read

before the Royal Society, on the request of Newton. Due credit was

given Harvey

for his discovery of the circulation of the blood; but Ray made the

fine point

that man was brother to the tree, and his life was derived from the

same

Source. When Willughby

died, in Sixteen

Hundred Seventy-two, he left Ray a yearly income of three hundred

dollars.

Doctor Johnson told Boswell that Ray had a collection of twenty

thousand

English bugs. Our botanical terminology comes more from John Ray than

from any

other man. Ray adopted wherever possible the names given by Aristotle,

so

loyal, loving and true was he to the Master. Ray died in Seventeen

Hundred

Five, aged seventy-six.  wo years after

the death of John Ray, in Seventeen Hundred Seven, was

born a baby who was destined to find biology a chaos, and leave it a

cosmos. wo years after

the death of John Ray, in Seventeen Hundred Seven, was

born a baby who was destined to find biology a chaos, and leave it a

cosmos.Linnĉus did for

botany what

Galileo had done for astronomy. John Ray was only a John the Baptist. Carl von Linne,

or Carolus

Linnĉus as he preferred to be called, was born in an obscure village in

the

Province of Smaland, Sweden. His father was a clergyman, passing rich

on forty

pounds a year. His mother was only eighteen years old when she bore

him, and

his father had just turned twenty-one. It was a poor parish, and one of

the

deacons explained that they could not afford a real preacher; so they

hired a

boy. Carl tells in

his journal, of

remembering how, when he was but four years old, his father would lead

his

congregation out through the woods and, all seated on the grass, the

father

would tell the people about the plants and herbs and how to distinguish

them. Back of the

parsonage there was a

goodly garden, where the young pastor and his wife worked many happy

hours.

When Carl was eight years of age, a corner of this garden was set apart

for his

very own. He pressed into

his service

several children of the neighborhood, and they carried flat stones from

the

near-by brook to wall in this miniature farm this botanical garden. The child that

hasn't a flowerbed

or a garden of its ownest own is being cheated out of its birthright. The evolution

of the child

mirrors the evolution of the race. And as the race has passed through

the

savage, pastoral and agricultural stages, so should the child. As a

people we

are now in the commercial or competitive stage, but we are slowly

emerging out

of this into the age of co-operation or enlightened self-interest. It is only a

very great man one

with a prophetic vision who can see beyond the stage in which he is. The stage we

are in seems the

best and the final one otherwise, we would not be in it. But to skip

any of

these stages in the education or evolution of the individual seems a

sore

mistake. Children hedged and protected from digging in the dirt develop

into

"third rounders," as our theosophic friends would say, that is,

educated non-comps vast top-head and small cerebellum people who

can

explain the unknowable, but who do not pay cash. Third rounders all

fit only

for the melting-pot! A tramp is one

who has fallen a

victim of arrested development and never emerged from the nomadic

stage; an

artistic dilettante is one who has jumped the round where boys dig in

the dirt

and has evolved into a missnancy. Young Carl

Linnĉus skipped no

round in his evolution. He began as a savage, robbing birds' nests,

chasing

butterflies, capturing bees, bugs and beetles. He trained goats to

drive,

hitched up a calf, fenced his little farm, and planted it with strange

and

curious crops. Clergymen once

were the only

schoolteachers, and in Sweden, when Linnĉus was a boy, there was a plan

of

farming children out among preachers that they might be educated.

Possibly this

plan of having some one besides the parents teach the lessons is good

I can

not say. But young Carl did not succeed save in disturbing the peace

among

the households of the half-dozen clergymen who in turn had him. The boy

evidently was a handsome

fellow, a typical Swede, with hair as fair as the sunshine, blue eyes,

and a

pink face that set off the fair hair and made him look like a

Circassian. He had energy

plus, and the way

he cluttered up the parsonages where he lodged was a distraction to

good

housewives: birds' nests, feathers, skins, claws, fungi, leaves,

flowers,

roots, stalks, rocks, sticks and stones and when one meddled with his

treasures, there was trouble. And there was always trouble; for the boy

possessed a temper, and usually had it right with him. The intent of

the parents was

that Carl should become a clergyman, but his distaste for theology did

not go

unexpressed. So perverse and persistent were his inclinations that they

preyed

on the mind of his father, who quoted King Lear and said, "How sharper

than a serpent's tooth it is to have a thankless child!" His troubles

weighed so upon the

good clergyman that his nerves became affected and he went to the

neighboring

town of Wexio to consult Doctor Rothman, a famed medical expert. The good

clergyman, in the course

of his conversation with the doctor, told of his mortification on

account of

the dulness and perversity of his son. Doctor Rothman

listened in

patience and came to the conclusion that young Mr. Linnĉus was a good

boy who

did the wrong thing. All energy is God's, but it may be misdirected. A

boy not

good enough for a preacher might make a good doctor an excess of

virtue is

not required in the recipe for a physician. "I'll cure you,

by taking

charge of your boy," said Rothman; "you want to make a clergyman of

the youth: I'll let him be just what he wants to be, a naturalist and a

physician." And it was so.  he year spent

by Linnĉus under the roof of Doctor Rothman was a pivotal

point in his life. He was eighteen years old. The contempt of Rothman

for the

refinements of education appealed to the young man. Rothman was blunt,

direct,

and to the point: he had a theory that people grew by doing what they

wanted to

do, not by resisting their impulses. he year spent

by Linnĉus under the roof of Doctor Rothman was a pivotal

point in his life. He was eighteen years old. The contempt of Rothman

for the

refinements of education appealed to the young man. Rothman was blunt,

direct,

and to the point: he had a theory that people grew by doing what they

wanted to

do, not by resisting their impulses.He was both

friend and comrade to

the boy. They rode together, dissected animals and plants, and the

young man

assisted in operations. Linnĉus had the run of the Doctor's library,

and

without knowing it, was mastering physiology. "I would adopt

him as my

son," said Rothman; "but I love him so much that I am going to

separate him from me. My roots have struck deep in the soil: I am like

the

human trees told of by Dante; but the boy can go on!" And so Rothman

sent him along to

the University of Lund, with letters to another doctor still more

cranky than

himself. This man was Doctor Kilian Stobĉus, a medical professor,

physician to

the king, and a naturalist of note. Stobĉus had a mixed-up museum of

minerals,

birds, fishes and plants. Everybody for a

hundred miles who

had a curious thing in the way of natural history sent it to Stobĉus.

Into this

medley of strange and curious things Linnĉus was plunged with orders to

"straighten it up." There was a German student also living with the

doctor, working for his board. Linnĉus took the lead and soon had the

young

German helping him catalog the curios. The spirit of

Ray had gotten

abroad in Germany, and Ray's books had been translated and were being

used in

many of the German schools. Linnĉus made a bargain with the German

student that

they should speak only German he wanted to find what was locked up in

those

German books on botany. Stobĉus was

lame and had but one

eye, so he used to call on the boys to help him, not only to hitch up

his

horse, but to write his prescriptions. Linnĉus wrote very badly, and

was chided

because he did not improve his penmanship, for it seems that in the

olden times

physicians wrote legibly. Linnĉus resented the rebuke, and was shown

the door.

He was gone a week, when Stobĉus sent for him, much to his relief. This

little

comedy was played several times during the year, through what Linnĉus

afterward

acknowledged as his fault. One would hardly think that the man who on

first

seeing the English gorse in full bloom fell on his knees, burst into

tears of

joy, and thanked God that he had lived to see this day, would have had

a fiery temper.

Then further, the gentle, spiritual qualities that Linnĉus in his later

life

developed give one the idea that he was always of a gentle nature. In indexing the

museum of Doctor

Stobĉus, Linnĉus found his bent. "I will never be a doctor," he said;

"but I can beat the world on making a catalog." And thus it

was: his genius lay

in classification. "He indexed and catalogued the world," a great

writer has said. After a year at

the University of

Lund, with more learned by working for his board than at school, there

was a

visit from Doctor Rothman, who had just dropped in to see his old

friend

Stobĉus. The fact was, Rothman cared a deal more for Linnĉus than he

did for

Stobĉus. "Weeds develop into flowers by transplanting only," said

Rothman to Linnĉus. "You need a different soil get out of here before

you get pot-bound." "But about

Cyclops?"

asked Linnĉus. "Let Cyclops go

to the

devil!" It was no use to ask permission of Stobĉus. Linnĉus was so

valuable that Stobĉus would not spare him. So Linnĉus

packed up and departed

between the dawn and the day, leaving a letter stating he had gone to

Upsala

because it seemed best and begging forgiveness for such seeming

ingratitude. When Linnĉus

got to Upsala he

found a letter from Doctor Cyclops, written in wrath, requesting him

never

again to show his face in Lund. Rothman also lost the friendship of

Stobĉus for

his share in the transaction.  hen Linnĉus

arrived at Upsala he had one marked distinction, according

to his own account he was the poorest student that had ever knocked

at the

gates of the University for admittance. Perhaps this is a mistake, for

even

though the young man had patched his shoes with birch bark, he was not

in debt. hen Linnĉus

arrived at Upsala he had one marked distinction, according

to his own account he was the poorest student that had ever knocked

at the

gates of the University for admittance. Perhaps this is a mistake, for

even

though the young man had patched his shoes with birch bark, he was not

in debt.And the youth

of twenty-one who

has health, hope, ambition and animation is not to be pitied. Poverty

is only

for the people who think poverty. It is five

hundred English miles

from Lund to Upsala. After his long, weary tramp, Linnĉus sat on the

edge of

the hill and looked down at the scattered town of Upsala in the valley

below. A

stranger passing by pointed out the college buildings, where a thousand

young

men were being drilled and disciplined in the mysteries of learning.

"Where is the Botanical Garden?" asked the newcomer. It was pointed

out to him. He

gazed on the site, carefully studied the surrounding landscape, and

mentally

calculated where he would move the Botanical Garden as soon as he had

control

of it. Let us anticipate here just long enough to explain that the

Upsala

Botanical Garden now is where Linnĉus said it should be. It is a most

beautiful

place, lined off with close-growing shrubbery. After traversing the

winding

paths, one reaches the lecture-hall, built after the Greek, with

porches,

peristyle and gently ascending marble steps. On entering the building,

the first

object that attracts the visitor is the life-size statue of Linnĉus. To the left, a

half-mile away, is

the old cathedral a place that never much interested Linnĉus. But

there now

rests his dust, and in windows and also in storied bronze his face,

form and

fame endure. In the meantime, we have left the young man sitting on a

boulder

looking down at the town ere he goes forward to possess it. He adjusts his

shoes with their

gaping wounds, shakes the dust from his cap, and then takes from his

pack a

faded neckscarf, puts it on and he is ready. Descending the

hill he forgets

his lameness, waives the stone-bruises, and walks confidently to the

Botanical

Garden, which he views with a critical eye. Next, he inquires for the

General

Superintendent who lives near. The young man presents his credentials

from

Rothman, who describes the youth as one who knows and loves the

flowers, and

who can be useful in office or garden and is not above spade and hoe.

The

Superintendent looks at the pink face, touched with bronze from days in

the

open air, notes the long yellow hair, beholds the out-of-door look of

fortitude

that comes from hard and plain fare, and inwardly compares these things

with

the lack of them in some of his students. "But this Doctor Doctor

Rothman who wrote this letter I do not have the honor of knowing

him,"

says the Superintendent. "Ah, you are

unfortunate," replies the youth; "he is a very great man, and I

myself will vouch for him in every way." Oh! this

glowing confidence of

youth before there comes a surplus of lime in the bones, or the touch

of

winter in the heart! The Superintendent smiled. Knock in faith and the

door

shall be opened there are those whom no one can turn away. A stray

bed was

found in the garret for the stranger, and the next morning he was

earnestly at

work cataloguing the dried plants in the herbarium, a task long delayed

because

there was no one to do it.  he study of

Natural History in the University of Upsala was, at this

time, at a low ebb. It was like the Art Department in many of the

American

colleges: its existence largely confined to the school catalog. There

were many

weeks of biting poverty and neglect for Linnĉus, but he worked away in

obscurity and silence and endured, saying all the time, "The sun will

come

out, the sun will come out!" Doctor Olaf Rudbeck had charge of the

chair

of Botany, but seldom sat in it. His business was medicine. He gave no

lectures, but the report was that he made his students toil at

cultivating in

his garden this to open up their intellectual pores. In the course of

his

work, Linnĉus devised a sex plan of classification, instead of the

so-called

natural method. He wrote out his ideas and submitted them to Rudbeck. he study of

Natural History in the University of Upsala was, at this

time, at a low ebb. It was like the Art Department in many of the

American

colleges: its existence largely confined to the school catalog. There

were many

weeks of biting poverty and neglect for Linnĉus, but he worked away in

obscurity and silence and endured, saying all the time, "The sun will

come

out, the sun will come out!" Doctor Olaf Rudbeck had charge of the

chair

of Botany, but seldom sat in it. His business was medicine. He gave no

lectures, but the report was that he made his students toil at

cultivating in

his garden this to open up their intellectual pores. In the course of

his

work, Linnĉus devised a sex plan of classification, instead of the

so-called

natural method. He wrote out his ideas and submitted them to Rudbeck.The learned

Doctor first

pooh-poohed the plan, then tolerated it, and in a month claimed he had

himself

devised it. On the scheme being explained to others there was

opposition, and

Rudbeck requested Linnĉus to amplify his notes into a thesis, and read

it as a

lecture. This was done, and so pleased was the old man that he

appointed

Linnĉus his adjunctus. In the Spring of Seventeen Hundred Thirty,

Linnĉus began

to give weekly lectures on some topic of Natural History. Linnĉus was now

fairly launched.

His animation, clear thinking, handsome face and graceful ways made his

lectures

very popular. Science in his hands was no longer the dull and turgid

thing it

had before been in the University. He would give a lecture in the hall,

and

then invite the audience to walk with him in the woods. He seemed to

know

everything: birds, beetles, bugs, beasts, trees, weeds, flowers, rocks

and

stones were to him familiar. He showed his

pupils things they

had walked on all their lives and never seen. The old

Botanical Garden that had

degenerated into a kitchen-garden for the Commons was rearranged and

furnished

with many specimens gathered round about. A system of

exchange was carried

on with other schools, and Natural History at Upsala was fast becoming

a

feature. Old Doctor Rudbeck hobbled around with the classes, and when

Linnĉus

lectured sat in a front seat, applauding by rapping his cane on the

floor and

ejaculating words of encouragement. Linnĉus was now

receiving

invitations to lecture at other schools in the vicinity. He made

excursions and

reports on the Natural History of the country around. The Academy of

Science of

Upsala now selected him to go to Lapland and explore the resources of

that

country, which was then little known. The journey was

to be a long and

dangerous one. It meant four thousand miles of travel on foot, by

sledge and on

horseback, over a country that was for the most part mountainous,

without

roads, and peopled with semi-savages. There were two

reasons why

Linnĉus should make the trip: One was he had

the hardihood and

the fortitude to do it. And second, he

was not wanted at

Upsala. He was becoming too popular. One rival professor had gone so

far as to

prefer formal charges of scientific heresy; he also made the telling

point that

Linnĉus was not a college graduate. The rule of the University was that

no

lecturer, teacher or professor should be employed who did not have a

degree

from some foreign University. Inquiry was

made and it was found

that Linnĉus had left the University of Lund under a cloud. Linnĉus was

confronted with the charge, and declined to answer it, thus practically

pleading guilty. So, to get him out of Upsala seemed a desirable thing,

both to

friends and to foes. His friends secured the commission for the Lapland

exploration, and his enemies made no objections, merely whispering,

"Good

riddance!" To be twenty-four, in good health, with hair like that of

General Custer, a heart to appreciate Nature, a good horse under you,

and a

commission from the State to do an important work, in your left-hand

breast-pocket what Heaven more complete! A reception was

tendered the

young naturalist in the great hall, and he addressed the students on

the

necessity of doing your work as well as you can, and being kind. Before

beginning his arduous and dangerous journey, Linnĉus went to Lund to

visit his

old patron, Doctor Stobĉus. Time, the great healer, had cured the

Doctor of his

hate, and he now spoke of Linnĉus as his best pupil. He had left

hastily by the

wan light of the moon, without leaving orders where his mail was to be

forwarded; but now he was received as an honored guest. All the little

misunderstandings they had were laughed over as jokes. From Lund,

Linnĉus went to his

home in Smaland to visit his parents. It is needless

to say that they

were very proud of him, and the villagers turned out in great numbers

to do him

honor, perhaps, in their simplicity, not knowing why.  he account of

the Lapland trip by Linnĉus is to be

found in his book, "Lachesis Lapponica." he account of

the Lapland trip by Linnĉus is to be

found in his book, "Lachesis Lapponica."The journey

covered over four

thousand miles and took from May to November, Seventeen Hundred

Thirty-one. The

volume is in the form of a daily journal, and is as interesting as

"Robinson Crusoe." There is no night there in Summer; but for all

this, Lapland is not a paradise. It is a great

stretch of desert,

vast steppes and lofty mountains, with here and there fertile valleys.

To be

out in the wide open, with no companions but a horse and a dog, filled

Linnĉus'

heart with a wild joy. As he went on, the road grew so rough that he

had to

part with the horse, which he did with a pang, but the dog kept him

company. To be educated

is to liberate the

mind from its trammels and fears to set it free, new-chiseled from

the rock.

Linnĉus reveled in the vast loneliness of the steppes and took a hearty

satisfaction in the hard fare. His gun and fishing-rod stood him in

good stead;

there were berries at times, and edible barks and watercress, and when

these

failed he had a little bag of meal and dried reindeer-tongues to fall

back

upon. The simplicity

of his living is

shown best in the fact that the expenses for the entire journey,

occupying

seven months, were only twenty-five pounds, or less than one hundred

twenty-five dollars. The Academy had set aside sixty pounds, and their

surprise

at having most of the money returned to them, instead of a demand being

made

for more, won them, hand and heart. He had hit the sturdy old burghers

in a

sensitive spot the pocketbook and they passed resolutions declaring

him the

world's greatest naturalist, and voted him a medal, to be cast at his

own

expense. Fame is delightful, but as collateral it does not rank high. Linnĉus was

without funds and

without occupation. He gave a course of lectures at the University on

his

explorations, where every seat was taken, and even the stage and

windows were

filled. The sprightliness, grace and intellect Linnĉus brought to bear

illumined his theme. When Linnĉus

lectured, all

classes were dismissed: none could rival him. His very excellence was

his

disadvantage. Jealousy was hot on his trail, for he was disturbing the

balance

of stupidity. A movement grew to force him from the college. Formal

charges

were made, and when the case came to a trial the even tenor of justice

was

disturbed by Linnĉus making an attack on Professor Rosen, his principal

enemy,

with intent to kill him. Dueling has been forbidden in all the

universities of

Sweden since the year Sixteen Hundred Eighty-two, and the diversion

replaced by

quartet singing. So when Linnĉus challenged his enemy to fight, and

warned him

he would kill him if he didn't fight, and also if he did, things were

in a bad

way for Linnĉus. The former

charges were dropped

to take up the more serious just as when a man is believed to be

guilty of

murder, no mention is made of his crime of larceny. Poor Linnĉus

was under the ban.

The enemy had won: Linnĉus must leave. But where should he go what

could he

do? No college would receive him after his being compelled to leave

Upsala for

riot. He decided that if disgrace were to be his on account of revenge,

he

would accept the disgrace. He would kill Rosen on sight and then either

commit

suicide or accept the consequences: it was all one! And so, laying

plans to

waylay his victim, he fell asleep and dreamed he had done the deed. He awoke in a

sweat of horror! He heard the

officers at the

door! He staggered to his feet, and was making wild plans to fight the

pursuers, when it occurred to him that he had only dreamed. He sat

down, faint,

but mightily relieved. Then he

laughed, and it came to

him that opposition was a part of the great game of life. To do a thing

was to

jostle others, and to jostle and be jostled was the fate of every man

of power.

"He that endureth unto the end shall be saved." The world was

before him the

flowers still bloomed, and plants nodded their heads in the meadows;

the summer

winds blew across the fields of wheat, the branches waved. He was

strong he

could plant and plow, or dig ditches, or hew lumber! Some one was

hammering on the

door; they had been knocking for fully five minutes ah! There had

been no

murder, so surely it was not the officers. He arose slowly

and opened the

door, murmuring apologies. A letter for Carolus Linnĉus! The letter was

from

Baron Reuterholm of Dalecarlia. It contained a draft for twenty-five

pounds,

"as a token of good faith," and begged that Linnĉus would accept charge

of an expedition to survey the natural resources of Dalecarlia in the

same way

that he had Lapland, only with greater minuteness. Linnĉus read the

letter

again. The draft fluttered from his fingers to the floor. "Pick that up!"

he

peremptorily ordered of the messenger. He wanted to see if the other

man saw it

too. The other man

did pick it up!

Linnĉus was not dreaming, then, after all!  his second

expedition had two objects: one was the better education of

Baron Reuterholm's two sons, and the other the survey. One of these

sons was at

the University of Upsala, and he had conceived such an admiration for

Linnĉus

that he had written home about him. No man knows what he is doing: we

succeed

by the right oblique. Little did Linnĉus guess that he was preparing

the way

for great good fortune. The second excursion was one of luxury. It

lacked all

the hardships of the first, and involved the management of a party.

Reuterholm

was a rich Jewish banker, and a man in close touch with all Swedish

affairs of

State. This time Linnĉus was provided with ample funds. his second

expedition had two objects: one was the better education of

Baron Reuterholm's two sons, and the other the survey. One of these

sons was at

the University of Upsala, and he had conceived such an admiration for

Linnĉus

that he had written home about him. No man knows what he is doing: we

succeed

by the right oblique. Little did Linnĉus guess that he was preparing

the way

for great good fortune. The second excursion was one of luxury. It

lacked all

the hardships of the first, and involved the management of a party.

Reuterholm

was a rich Jewish banker, and a man in close touch with all Swedish

affairs of

State. This time Linnĉus was provided with ample funds.Linnĉus had a

genius for system

a head for business. He classified men, and systematized his work like

a

general in the field. There were seven young naturalists in the party,

and to

each Linnĉus assigned a special work, with orders to hand in a written

report

of progress each evening. That the "Economist" or steward of the

party was an American lends an especial note of interest for us. After

Dalecarlia it was to be America! In money

matters he was punctilious

and accurate, the result of his early training in making both ends

meet. The

habits of thrift, industry, energy and absolute honesty had made him a

marked

man there is not so much competition along these lines. The maps,

measurements, drawings,

and the exact, short, sharp, military reports turned in at regular

intervals to

the Baron won that worthy absolutely. Linnĉus was a

businessman as well

as a naturalist. It would require a book to tell of the glorious

half-gypsy

life of these eight young men, moving slowly through woods, across

plains, over

mountains and meadows, studying soil, rocks, birds, trees and flowers,

collecting and making records. Camping at

night by flowing

streams, awakening with the dawn and cooking breakfast by the campfire

in a

silence that took up their shouts of laughter in surprise, and echoed

them back

from the neighboring hills! At last the journey was ended. Linnĉus had

proved

his ability to teach his animation, good-cheer and friendly qualities

brought

his pupils very close to him. Reuterholm insisted that he should attach

himself

to the rising little college at Fahlun. There he met Doctor Morĉus, a

man of

much worth in a scientific way. At his house Linnĉus made his home.

There was a

daughter in the household, Sara Elizabeth, tall, slender, appreciative

and

studious. One of the Reuterholms had courted her, but in vain. There were the

usual results, and

when Carolus and Sara Elizabeth came to Doctor Morĉus hand in hand for

his

blessing, he granted it as good men always do. Then the Doctor gave

Linnĉus

some good advice go to Holland or somewhere and get a doctor's

degree. The

enemies at Upsala called Linnĉus "the gypsy scientist." Silence them

Linnĉus was now a great man, and the world would yet acknowledge it.

Sara

Elizabeth agreed in all of the propositions. Love, they say,

is blind, but

sometimes love is a regular telescope. This time love saw things that

the

learned men of Upsala failed to discover their diagnosis was wrong.

Linnĉus

had prepared a thesis on intermittent fever, and he was assured that if

he

presented this thesis at the medical school at Harderwijk, Holland,

with

letters from Baron Reuterholm and Doctor Morĉus, it would secure him

the much

desired M.D. A few months,

at most, would

suffice. He could then return to Fahlun and take his place as a

practising

physician and a professor in the college, marry the lady of his choice

and live

happy ever afterward. So he started

away southward. In

due time, he arrived at Harderwijk and read his thesis to the faculty.

Instead

of the callow youth, such as they usually dealt with, they found a

practised

speaker who defended his points with grace and confidence. The degree

was at

once voted, and a "cum laude" thrown in for good measure. Linnĉus was

asked to remain there and give a course of lectures on natural history.

This he

did. Before going home he thought he would take a little look in on

Leyden, at

that time the bookmaking and literary center of the world. At Leyden he

met

Gronovius, the naturalist, who asked him to remain and give lectures at

the

University. He did so, and incidentally showed Gronovius the manuscript

of his

book on the new system of botanic classification. Gronovius was

so delighted that

he insisted on having the book printed by the Plantins at his own

expense. Here

was a piece of good fortune Linnĉus had not anticipated. Linnĉus now

settled down to read

the proofs and help the work through the presses. But he never idled an

hour. He studied,

wrote and lectured,

and made little excursions with his friends through the fields. The

book

finished, he hastened to send copies back to Fahlun to Sara Elizabeth,

saying

he must see Amsterdam and then go to Antwerp to visit his new-found

printer-friends there, and then go home! At Amsterdam he

remained a whole

year, living at the house of Burman, the naturalist. The wealthy

banker, Cliffort,

first among amateur botanists of his day, invited Linnĉus to visit him

at his

country-house at Hartecamp. Here he saw the finest garden he had ever

looked

upon. Cliffort had copies of Linnĉus' book and he now insisted that the

author

should remain, catalog his collection and issue the book with the help

of the

Plantins, all without regard to cost. It took a year to get the work

out, but

it yet remains one of the finest things ever attempted in a bookmaking

way on

the subject of botany. About the same

time, with the

help of Cliffort, Linnĉus published another big book of his own called,

"Fundamenta Botanica." This book was taken up at Oxford and used as a

textbook, in preference to Ray. Linnĉus

received invitations from

England and was persuaded to take a trip across to that country. He

visited

Oxford and London, and was received by scientific men as a conquering

hero. He

saw Garrick act and heard George Frederick Handel, where the crowd was

so great

that a notice was posted requesting gentlemen to come without swords

and ladies

without hoops. Handel composed an aria in his honor. Returning to

Leyden, Linnĉus was

urged by the municipality to remain and rearrange the public

flower-gardens and

catalog the rare plants at the University. This took a year, in which

three

more books were issued under his skilful care. He now started

for home in

earnest, by way of Paris, with what a contemporary calls "a trunkful of

medals." Paris, too, had

honors and

employment for the great botanist, but he escaped and at last reached

Fahlun.

He had been gone nearly four years, and during the interval had

established his

place in the scientific world as the first botanist of the time. "It was love

that sent me

out of Sweden, and but for love I would never have returned," he wrote. Linnĉus and

Sara Elizabeth were

married June Twenty-six, Seventeen Hundred Thirty-nine. Now the

unexpected happened:

Upsala petitioned Linnĉus to return, and the man who headed the

petition was

the one who had driven him away and who came near being killed for his

pains.

Linnĉus and his wife went to Upsala, rich, honored, beloved. Linnĉus shifted

the scientific

center of gravity of all Europe to a town, practically to them obscure,

a thing

they themselves scarcely realized. Henceforth, the

life of Linnĉus

flowed forward like a great and mighty river everything made way for

him. He

was invited by the King of Spain to come to that country and found a

School of

Science, and so lavish were the promises that they surely would have

turned the

head of a lesser man. Universities in many civilized countries honored

themselves by giving him degrees. In Seventeen

Hundred Sixty-one,

the King of Sweden issued a patent of nobility in his honor, and

thereafter he

was Carl von Linne. In England he was known as Sir Charles Linn. Sainte-Beuve,

the eminent French

critic, says that the world has produced only about half a dozen men

who

deserve to be placed in the first class. The elements that make up this

super-superior man are high intellect, which abandons itself to the

purpose in

hand, careless of form and precedent; indifference to obstacles and

opposition;

and a joyous, sympathetic, loving spirit that runs over and inundates

everything it touches, all with no special thought of personal

pleasure,

gratification or gain. Linnĉus seems

in every way to

fill the formula. |