| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2018 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Little Journeys To the Homes of Great Scientists Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

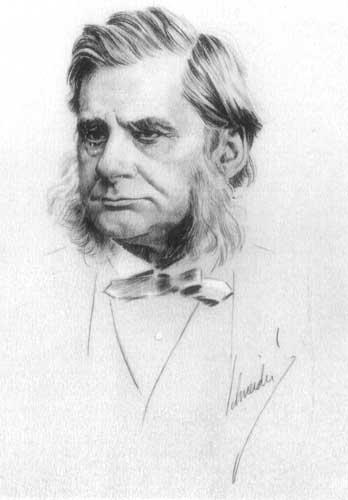

THOMAS H. HUXLEY

That man, I

think, has a liberal

education whose body has been so trained in youth that it is the ready

servant

of his will, and does with ease and pleasure all that, as a mechanism,

it is

capable of; whose intellect is a clear, cold, logic engine, with all

its parts

of equal strength and in smooth running order, ready, like a

steam-engine, to

be turned to any kind of work and to spin the gossamers as well as

forge the

anchors of the mind; whose mind is stored with the knowledge of the

great

fundamental truths of Nature and the laws of her operations; one who,

no

stunted ascetic, is full of life and fire, but whose passions have been

trained

to come to heel by a vigorous will, the servant of a tender conscience;

one who

has learned to love all beauty, whether of Nature or of art, to hate

all

vileness, and to esteem others as himself. Thomas Henry

Huxley

hat was a great

group of thinkers to which Huxley

belonged. hat was a great

group of thinkers to which Huxley

belonged.The Mutual

Admiration Society

forms the sunshine in which souls grow great men come in groups. Sir

Francis

Galton says there were fourteen men in Greece in the time of Pericles

who made

Athens possible. A man alone is only a part of a man. Praxiteles by

himself could have

done nothing. Ictinus might have drawn the plans for the Parthenon, but

without

Pericles the noble building would have remained forever the stuff which

dreams

are made of. And they do say that without Aspasia Pericles would have

been a

mere dreamer of dreams, and Walter Savage Landor overheard enough of

their

conversation to prove it. William Morris

and seven men

working with him formed the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and gave the

workers and

doers of the world an impetus they yet feel. Cambridge and

Concord had seven

men who induced the Muses to come to America and take out papers. These men of

the Barbizon School

tinted the entire art world: Millet, Rousseau, Daubigny, Corot, Diaz.

And the

people who worked a complete revolution in the theological thought of

Christendom were these: Darwin, Spencer, Mill, Tyndall, Wallace, Huxley

and,

yes, George Eliot, who bolstered the brain of Herbert Spencer when he

was

learning to think for himself. When the

victory had become a

rout, there were many others who joined forces with the evolutionists;

but at

first the thinkers named above stood together and received the rather

unsavory

gibes and jeers of those who get their episcopopagy and science from

the same

source. Darwin was the

only man in the

group who was a university graduate, and he once said that he owed

nothing to

his Alma Mater, save the stimulus derived from her disapproval. For the work

these men had to do

there was no precedent: no one had gone before and blazed a trail. Learning, like

capital, is timid;

but ignorance coupled with a desire to know, is bold. Do I then make a

plea for

ignorance? Yes, most assuredly. It is just as well not to know so much,

as to

be a theologian and know so many things that are not true. Learning and

institutions of

learning subdue men into conformity; only the man who belongs to

nothing is

free; and ignorance, as well as a certain indifference to what the

world has said

and done, is a necessary factor in the character of him who would do a

great

work. It was the combined ignorance and boldness of Columbus that made

it

possible for him to give the world a continent. Yet the man who

has not had a

college training often feels he has somehow missed something valuable:

there is

timidity and hesitation when he is in the presence of those who have

had

"advantages." And Huxley felt this loss, more or less, up to his

thirty-fifth year, when Fate had him cross swords with college men, and

then

the truth became his that if he had had the regular university

training, it was

quite probable that he would have accepted the doctrines the

universities

taught, and would then have been in the camp of the "enemy," instead

of with what he called the "blessed minority." Isolation is a

great aid to the

thinker. Some of the best books the world has ever known were written

behind

prison-bars; exile has done much for literature, and a protracted

sea-voyage

has allowed many a good man to roam the universe in imagination. Some

of

Macaulay's best essays were written on board slow-going sailing-ships

that were

blown by vagrant winds from England to India. Darwin, Hooker and

Huxley, all

got their scientific baptism on board of surveying-ships, where time

was

plentiful and anything but fleeting, and most everything else was

scarce. Huxley was only

assistant surgeon

on the "Rattlesnake," and above him was a naturalist who much of his

time lay in his bunk and read treatises on this and also on that. Huxley was the

seventh child of a

plodding schoolteacher, born on the seventh day of the week on a

seventh-floor

back, he used to say. His genius for work came from his mother, a

tireless,

ambitious woman, who got things done while others were discussing them.

"Had

she been a man, she would have been leader of the Opposition in the

House of

Commons," her son used to say. College

education was not for

that goodly brood a living was the first thing, so after a good

drilling in

the three R's, Thomas Huxley was apprenticed to a pharmacist who paid

him six

shillings a week, a sum that the boy conscientiously gave to his mother. Oh, if in our

school teaching we

could only teach this one thing: a great thirst for knowledge! But this

desire

we can not impart: it is trial, difficulty, obstacle, deprivation and

persecution that make souls hunger and thirst after knowledge. Young

Huxley

wanted to know. His thoroughness in the drugstore won the admiration of

the

doctors whose prescriptions he compounded, and several of them loaned

him books

and took him to clinics; and at seventeen we find him with a Free

Scholarship

in Charing Cross Hospital, serving as nurse and assistant surgeon. Then

came

the appointment as assistant surgeon in the Navy, and the appointment

to

"H.M.S. Rattlesnake," bound on a four-year trip to the Antipodes, all

quite as a matter of course. Life is a

sequence: this happened

today because you did that yesterday. Tomorrow will be the result of

today. The general

idea of evolution was

strong in the mind of young Huxley. He realized that Nature was moving,

growing, changing all things. He had studied embryology, and had seen

how the

body of a man begins as a single minute mass of protoplasm, without

organs or

dimensions. Behind the ship

was his dragnet,

and he worked almost constantly recording the different specimens of

animal and

vegetable life that he thus secured. The jellyfish attracted him most. To the ship's

naturalist,

jellyfish were jellyfish, but Huxley saw that there were many kinds,

distinct,

separate, peculiar. He began to dissect them and thus began his book on

jellyfish, just as Darwin wrote his work on barnacles. Huxley vowed to

himself that

before the "Rattlesnake" got back to England he would know more about

jellyfish than any other living man. That his ambition was realized no

one now

disputes. Among his first

discoveries, it

came to him with a thrill that a certain species of jellyfish bears a

very

close resemblance to the human embryo at a certain stage. And he

remembered the dictum of

Goethe, that the growth of the individual mirrors the growth of the

race. And

he paraphrased it thus: "The growth of the individual mirrors the

growth

of the species." So filled was he with the thought that he could not

sleep, so he got up and paced the deck and tried to explain his great

thought

to the second mate. He was getting ready for "The Origin of Species,"

which he once said to Darwin he would himself have written, if Darwin

had been

a little more of a gentleman and had held off for a few years. It was on board

the

"Rattlesnake" that Huxley wrote this great truth: "Nature has no

designs or intentions. All that live exist only because they have

adapted

themselves to the hard lines that Nature has laid down. We progress as

we

comply."  n Australia,

while waiting for his ship to locate

and map a dangerous reef, Huxley went ashore, and as he playfully

expressed it,

"ran upon another." n Australia,

while waiting for his ship to locate

and map a dangerous reef, Huxley went ashore, and as he playfully

expressed it,

"ran upon another."The name of the

most excellent

young woman who was to become his wife was Henrietta Heathorn; and

Julian

Hawthorne has discovered that she belongs to the same good stock from

whence

came our Nathaniel of Salem. It did not take

the young

naturalist and this stranded waif, seven thousand miles from home, long

to see

that they had much in common. Both were eager for truth, both had the

ability

to cut the introduction and reach live issues directly. "I saw you were

a

woman with whom only honesty would answer," he wrote her thirty years

after. He was still in love with her. Yet she was a

proud soul, and no

assistant surgeon on an insignificant sloop would answer her when he

got his

surgeon's commission she would marry him. And it was seven years before

she

journeyed to England alone with that delightful object in view. He had

to serve

for her as Jacob did for Rachel, with this difference: Jacob loved

several, but

Thomas Huxley loved but one. Huxley's wife

was his companion,

confidante, comrade, friend. I can not recall another so blest, in all

the

annals of thinking men, save John Stuart Mill. "I tell her everything I

know, or guess, or imagine, so as to get it straight in my own mind,"

he

said to John Fiske. In that most

interesting work,

"Life and Lessons of Huxley," compiled by his son Leonard, are

constant references and allusions to this most ideal mating. In reply

to the

question, Is marriage a failure? I would say, "No, provided the man

marries a woman like Huxley's wife, and the woman marries a man like

Huxley."  here is a

classic aphorism which runs about this way, "Knock and

the world knocks with you; boost and you boost alone." Like most

popular

sayings this is truth turned wrong side out. here is a

classic aphorism which runs about this way, "Knock and

the world knocks with you; boost and you boost alone." Like most

popular

sayings this is truth turned wrong side out.John Fiske once

called Thomas

Huxley an "appreciative iconoclast." That is to say, Huxley was a

persistent protester (which is different from a protestant), and at the

same

time, he was a friend who never faltered and grew faint in time of

trouble.

Huxley always sniffed the battle from afar and said, Ha! Ha! There be those

who do declare

that the success of Huxley was owing to his taking the tide at the

flood, and

riding into high favor on the Darwinian wave. To say that there would

have been

no Huxley had there been no Darwin would be one of those unkind cuts

the

cruelty of which lies in its truth. It is equally

true that if there

had been no Lincoln there would have been no Grant; but Grant was a

very great

man just the same so why raise the issue! Darwin summed

up and made nebulζ

of the truths which Huxley had, up to that time, held only in gaseous

form. Darwin was born

in the immortal

year Eighteen Hundred Nine. Huxley was born in Eighteen Hundred

Twenty-five.

When "The Origin of Species" was published in Eighteen Hundred

Fifty-nine, Thomas Huxley was thirty-four years old. He had made his

four

years' trip around the world on the surveying-ship "Rattlesnake,"

just as Darwin had made his eventful voyage on the "Beagle." These men in

many ways had

paralleled each other; but Darwin had sixteen years the start, and

during these

years he had steadily and silently worked to prove the great truth that

he had

sensed intuitively years before in the South Seas. "The Origin of

Species"

sheds light in ten thousand ways on the fact that all life has evolved

from

very lowly forms and is still ascending: that species were not created

by fiat,

but that every species was the sure and necessary result of certain

conditions. Until "The

Origin of

Species" was published, and for some years afterward, the Immutability

of

Species was taught in all colleges, and everywhere accepted by the

so-called

learned men. Goethe had

somewhat dimly

prophesied the discovery of the Law of Evolution, but his ideas on

natural

science were regarded by the schools as quite on a par with those of

Dante:

neither was taken seriously. Darwin proved

his hypothesis.

Doubtless, very many schoolmen would have accepted the theory, but to

admit that

man was not created outright, complete, and in his present form, or

superior to

it, seemed to evolve a contradiction of the Mosaic account of Creation,

and the

breaking up of Christianity. And these things done, many thought, would

entail

moral chaos, destruction of private interests and moral confusion being

one and

the same thing to those whose interests are involved. And so for

conscience'

sake, Darwin was bitterly assailed and opposed. Opportunity,

which knocks many

times at each man's door, rapped hard at Huxley's door in Eighteen

Hundred

Sixty. It was at Oxford, at a meeting of the British Association for

the

Advancement of Science: "A big society with a slightly ironical

name," once said Huxley. The audience was large and fashionable,

delegates

being present from all parts of the British Empire. "The Origin of

Species"

had been published the year before, and tongues were wagging. Darwin

was not

present; but Huxley, who was known to be a personal friend of Darwin,

was in

his seat. The intent of the chairman was to keep Darwin and his

pestiferous

book out of all the discussions: Darwin was a good man to smother with

silence. But Samuel

Wilberforce, Bishop of

Oxford, in the course of a speech on another subject began to run short

of

material, and so switched off upon a theme which he had already

exploited from

the pulpit with marked effect. All public speakers carry this

boiler-plate

matter for use in time of stress. The Bishop

began to denounce

"those enemies of the Church and Society who make covert attacks upon

the

Bible in the name of Science." He warmed to his theme, and by a

specious

series of misstatements and various appeals to the prejudices of his

audience

worked the assemblage up to a high pitch of hilarity and enthusiasm.

Toward the

close of his speech he happened to spy Huxley seated near, and pointing

a pudgy

finger at him, "begged to be informed if the learned gentleman was

really

willing to be regarded as a descendant of a monkey?" As the Bishop

sat down, there was

a wild burst of applause and much laughter, but amid the din were

calls,

"Huxley! Huxley!" These shouts increased as it came over the people

that while the Bishop had made a great speech, he had gone a trifle too

far in

ridiculing a member who up to this time had been silent. The good

English

spirit of fair play was at work. Still Huxley sat silent. Then the

enemy,

thinking he was completely vanquished, took up the cry with intent to

add to

his discomfiture: "Huxley! Huxley!" Slowly Huxley

arose. He stood

still until the last buzzing whisper had died away. When he spoke it

was in so

low a tone that people leaned forward to catch his words. Huxley knew his

business: his

slowness to speak created an atmosphere. There was no jest in his voice

or

manner. The air grew tense. His quiet

reserve played itself

off against the florid exuberance of the Bishop. The Bishop was not a

man given

to exact statements: his knowledge of science was general, not specific. Huxley

demolished his card house

point by point, correcting the gross misstatements, and ending by

saying that

since a question of personal preferences had been brought into the

discussion

of a great scientific theme, he would confess that if the alternatives

were a

descent on the one hand from a respectable monkey, or on the other from

a

Bishop of the Church of England who could stoop to misrepresentation

and

sophistry and who had attempted in that presence to throw discredit

upon a man

who had given his life to the cause of science, then if forced to

decide he

would declare in favor of the monkey. When Huxley

took his seat, there

was a silence that could be felt. Several ladies fainted. There were

fears that

the Bishop would reply, and to keep down such a possible unpleasant

move the

audience now applauded Huxley roundly, and amid the din the chairman

declared

the meeting adjourned. From that time forward Huxley was famous throughout England as a man to let alone in public debate.  t is a fine

thing to be a great scientist, but it

is a yet finer thing to be a great man. The one element in Huxley's

life that

makes his character stand out clear, sharp and well defined was his

steadfast

devotion to truth. The only thing he feared was self-deception. When he

uttered

his classic cry in defense of Darwin, there was no ulterior motive in

it; no

thought that he was attaching himself to a popular success; no idea

that he was

linking his name with greatness. t is a fine

thing to be a great scientist, but it

is a yet finer thing to be a great man. The one element in Huxley's

life that

makes his character stand out clear, sharp and well defined was his

steadfast

devotion to truth. The only thing he feared was self-deception. When he

uttered

his classic cry in defense of Darwin, there was no ulterior motive in

it; no

thought that he was attaching himself to a popular success; no idea

that he was

linking his name with greatness.What he felt

was true, he

uttered; and the strongest desire of his soul was that he might never

compromise with the error for the sake of mental ease, or accept a

belief

simply because it was pleasant. Huxley once

wrote this terse

sentence of Gladstone: "It is to me a serious thing that the destinies

of

this great country should at present be to a great extent in the hands

of a man

who, whatever he may be in the affairs of which I am no judge, is

nothing but a

copious shuffler in those that I do understand." Gladstone crossed

swords

with Huxley, Spencer and Robert Ingersoll, and in each case his

blundering

intellect looked like a raft of logs compared with a steamboat that

responds to

the helm. Gladstone was a man of action, and silence to such is most

becoming. He had a

belief, that was enough;

he should have hugged it close, and never stood up to explain it. Let

us vary a

simile just used: Lincoln once referred to an opponent as being "like a

certain steamboat that ran on the Sangamon. This boat had so big a

whistle that

when she blew it, there wasn't steam enough to make her run, and when

she ran

she couldn't whistle." Huxley, Spencer

and Robert

Ingersoll, all made Gladstone cut for the woods and cover his retreat

in a

cloud of words. Ingersoll once said that in replying to Gladstone he

felt like

a man who had been guilty of cruelty to children. If one wants to

see how pitifully

weak Gladstone could be in an argument, let him refer to the "North

American Review" for Eighteen Hundred Eighty-two. Yet Ingersoll

was surely lacking

in the passion for truth that characterized Huxley. Ingersoll was

always a

prosecutor or a defender: the lawyer habit was strong upon him. Just a

little

more bias in his clay and he would have made a model bishop. His stock of

science was almost

as meager as was that of Samuel Wilberforce, and he seldom hesitated to

turn

the laugh on an adversary, even at the expense of truth. When brought

to book

for his indictment of Moses without giving that great man any credit

for the

sublime things he did do, or making allowances for the barbaric horde

with

which he had to deal, Bob evaded the proposition by saying, "I am not

the

attorney of Moses: he has more than three million men looking after his

case." Again, in that

most charming

lecture on Shakespeare, Ingersoll proves that Bacon did not write the

plays, by

picking out various detached passages of Bacon, which no one for a

moment ever

claimed revealed the genius of the man. With equal

plausibility we could

prove that the author of Hamlet was a weakling, by selecting all the

obscure

and stupid passages, and parading these with the unexplained fact that

the play

opens with the spirit of a dead man coming back to earth, and a little

later in

the same play Shakespeare has the man who interviewed the ghost tell of

"that bourne from whence no traveler returns." Even Shakespeare was

not a genius all the time. And Ingersoll, the searcher for truth,

borrowed from

his friends, the priests, the cheerful habit of secreting the

particular thing

that would not help the cause in hand. But one of the best things in

Ingersoll's character was that he realized his lapses and in private

acknowledged them. On reading the

smooth, florid and

plausible sophistry of Wilberforce, Ingersoll once said: "Be easy on

Soapy

Sam! A few years ago, a little shifting of base on the part of my

ancestors,

and I would probably have had Soapy Sam's job." This resemblance of opposites makes a person think of that remark applied to Voltaire. "He was the father of all those who wear shovel-hats."  hen Thomas

Huxley and his wife arrived in New York

in Eighteen Hundred Seventy-six, on a visit to the Centennial

Exhibition, this

interesting item was flashed over the country, "Huxley and his titled

bride have arrived in New York on their wedding-journey." hen Thomas

Huxley and his wife arrived in New York

in Eighteen Hundred Seventy-six, on a visit to the Centennial

Exhibition, this

interesting item was flashed over the country, "Huxley and his titled

bride have arrived in New York on their wedding-journey."This item

caused Mr. and Mrs.

Huxley both of them royal democrats more joy than did the most

complimentary interview. At home they had left a charming little brood

of seven

children, three of them nearly grown-ups. Huxley sent

Tyndall, who a few

months before had married a daughter of Lord Hamilton, the clipping and

this

note: "You see how that once I am in a democratic country I am pulling

all

the honors I can in my own direction." The next letter the Huxleys

received from Tyndall was addressed, "Sir Thomas and Lady Huxley."

Huxley never stood in much awe of the nobility; he evidently felt that

there

was another kind of which he himself in degree was heir. Huxley never

had a

better friend than Sir Joseph Hooker, and we see in his letters such

postscripts as this: "Dear Sir

Joseph: Do come

and dine with us; it is a month since we have seen your homely old

phiz."

And Sir Joseph replies that he will be on hand the next Sunday evening

and

offers this mild suggestion, "Scientific gents as has countenances as

curdles milk should not cast aspersions on men made in image of Maker."  he wordy duel

between Huxley and Gladstone prompted Toole, the great

comedian, to send a box of grease-paints to Huxley with a note saying,

"These are for you and Gladstone to use when you make up." It was a

joke so subtle and choice that the Huxleys, always dear friends of

Toole,

laughed for a week. he wordy duel

between Huxley and Gladstone prompted Toole, the great

comedian, to send a box of grease-paints to Huxley with a note saying,

"These are for you and Gladstone to use when you make up." It was a

joke so subtle and choice that the Huxleys, always dear friends of

Toole,

laughed for a week.Poor Gladstone

required a diagram

when he heard of the procedure; and then, not being trepanned for the

pleasantry, remarked that if Toole and Huxley collaborated on the

stage, it

would be eminently the proper thing, and in his mind there was little

choice

between them, both being fine actors. Later, we hear

of Huxley saying

he thought of sending the box of grease-paints to Gladstone, so the

Premier

could use them in making up with God; as for himself, he was like

Thoreau and

had never quarreled with Him. Huxley had many

friendships with

people seemingly outside of his own particular line of work. Henry

Irving, the

Reverend Doctor Parker, John Fiske and Hall Caine once met at one of

Huxley's

"Tall Teas," and Doctor Parker explained that he personally had no

objection to visiting with sinners. For Parker,

Huxley had a great

admiration and often attended the Thursday noon meeting at the Temple,

"to

see and hear the greatest actor in England," a compliment which Parker

much appreciated, otherwise he would not have repeated it. "If I ever

take

to the stage, I will play the part of Jacques or Touchstone," said

Huxley. John Fiske in

his delightful

essay on Huxley said that in the Huxley home there was more jest, joke

and

banter than in any other place in London. The air was surcharged with

mirth,

and puns, often very bad ones, were tossed back and forth with great

recklessness. At one time

John Fiske was at the

Huxleys and the dual or multiple nature of man came up for discussion.

Huxley

spoke of how very often men who were gentle and charming in their homes

were

capable of great crimes, and of how, on the other hand, a man might

pass in the

world as a philanthropist, and yet in his household be a veritable

autocrat and

tyrant. Fiske then

incidentally mentioned

the case of Doctors Parker and Webster of Harvard men of intellect

and worth.

These men brooded over a misunderstanding that grew into a grudge and

eventually hatched murder. One worthy professor killed the other, cut

up the

body, and tried to burn it in a chemist's retort. Only the great

difficulty of

reducing the human body to ashes caused the murder to out, and brought

about

the hanging of a scientist of note. "Yes, I have

thought of the

difficulty of disposing of a dead body," said Huxley, solemnly; "and

often when on the point of committing murder this was the only thing

that made

me hesitate!" "Oh, Pater, we

are ashamed

of you," said his three lovely daughters in concert. Huxley's ability

to

joke and his appreciation of the ludicrous marked him, in the mind of

John

Fiske, as the greatest thinker of his time. The humorist knows values,

and that

is why he laughs. Sensibility is, in fact, the basic element of wit.  uxley's duties

on the "Rattlesnake" were not in the line of

science. His rank was assistant surgeon; but as sure-enough surgeons

were only

sent out on bigger craft, he was this ship's doctor. uxley's duties

on the "Rattlesnake" were not in the line of

science. His rank was assistant surgeon; but as sure-enough surgeons

were only

sent out on bigger craft, he was this ship's doctor.With the

captain's help the men

were kept busy, but not too busy, and the food and regulations were

such that

about all Huxley had to do was to look upon his work and pronounce it

good. As a physician,

Huxley practised

throughout his life the science of prevention. "With a

prophetic vision,

quite unconscious, my parents named me after that particular apostle I

was to

admire most," once said Huxley. He was a doubter by instinct, and

approached the world of Nature as if nothing were known about it. His work on the

Medusa won him

the recognition of the British Society, and this secured him the

coveted

surgeon's commission. Two tragedies confront man on his journey through

life one

when he wants a thing and can not get it; the other when he gets the

thing and

finds he does not want it. Having secured

his surgeon's

commission, Huxley felt a strong repulsion toward devoting his life to

the

abnormal. "I am a

scientist by nature,

and my business is to teach," he wrote to his affianced wife. These

were

wise words which he had learned from her, but which he repeated,

seemingly

quite innocent of their source. We take our own wherever we find it. Miss Heathorn

admired a surgeon,

but loved a scientist, and Huxley being a man was making a heroic

struggle to

be what the young woman most wished. Love supplies an ideal and that

is the

very best thing love does, with possibly an exception or two. So behold

a

ship's surgeon in London, full-fledged, refusing offers of position,

and even

declining to take a choice of ships, for such is the perversity of

things

animate and inanimate that, when we do not want things, Fate brings

them to us

on silver platters and begs us to accept. We win by indifference as

much as by

desire. "I have

declined to ship on

board the 'Cormorant' as head surgeon, and have applied to the

University of

Toronto for a position as Professor of Natural History." And so America

had Huxley flung

at her head. Toronto considered, and the Canadians sat on the case, and

after

considerable correspondence, the vacant chair was given to Professor

Baldini of

the Whitby Ladies College. It was a close call for Canada! Huxley had

imagined

that the New World offered special advantages to a rising young person

of

scientific bent, but now he secured a marriage-license and settled down

as

lecturer at the School of Mines. A little later he began to teach at

the Royal

College of Surgeons, with which institution he was to be connected the

rest of

his life, and fill almost any chair that happened to be vacant. From the time

he was twenty-seven

Huxley never had to look for work. He was known as a writer of worth,

and as a

lecturer his services were in demand. He became

President of the

Geological and Ethnological Society; was appointed Royal Commissioner

for the

Advancement of Science; was a member of the London School Board;

Secretary of

the Royal Society; Lord Rector of the University of Aberdeen; President

of the

Royal Society; and refused an offer to become Custodian of the British

Museum,

a life position, and where he had once applied for a clerkship. In letters to

Darwin he

occasionally signed his name with all titles added, thus, "Thomas Henry

Huxley, M.B., M.D., Ph.D., LL.D., F.R.S. of Her Majesty's Navy." Huxley was a

forceful and

epigrammatic writer, and had a command of English second to no

scientist that

England has ever produced. He was the only one of his group who had a

distinct

literary style. As a speaker he was quiet, deliberate, decisive, sure;

and he

carried enough reserve caloric so that he made his presence felt in any

assemblage before he said a word. In oratory it is personality that

gives

ballast. Of his forty or

so published

books, "Man's Place in Nature," "Elementary Physiology" and

"Classification of Animals" have been translated into many languages,

and now serve as textbooks in various schools and colleges. Huxley is the

founder of the

so-called Agnostic School, which has the peculiarity of not being a

school. The

word "agnostic" was given its vogue by Huxley. To superficial people

it was quite often used synonymously with "infidel" and

"freethinker," both words of reproach. To Huxley it meant simply one

who did not know, but wished to learn. The controlling

impulse of Huxley's

life was his absolute honesty. To pretend to believe a thing against

which

one's reason revolts, in order to better one's place in society, was to

him the

sum of all that was intellectually base. He regarded man

as an undeveloped

creature, and for this creature to lay the flattering unction to his

soul that

he was in special communication with the Infinite, and in possession of

the

secrets of the Creator, was something that in itself proved that man

was as yet

in the barbaric stage. Said Huxley: "As to the final truths of Creation and Destiny, I am an agnostic. I do not know, hence I neither affirm nor deny."  umor and

commonsense usually go together. Huxley had a goodly stock of

both. When George Eliot died, there was a very earnest but ill-directed

effort

made to have her body buried in Westminster Abbey. Huxley, being close

to the

Dean, serving with him on several municipal boards, was importuned by

Spencer

to use his influence toward the desired end. Huxley saw the incongruity

of the

situation, and in a letter that reveals the logical mind and the

direct,

literary, Huxley quality, he placed his gentle veto on the proposition

and thus

saved the "enemy" the mortification of having to do so. umor and

commonsense usually go together. Huxley had a goodly stock of

both. When George Eliot died, there was a very earnest but ill-directed

effort

made to have her body buried in Westminster Abbey. Huxley, being close

to the

Dean, serving with him on several municipal boards, was importuned by

Spencer

to use his influence toward the desired end. Huxley saw the incongruity

of the

situation, and in a letter that reveals the logical mind and the

direct,

literary, Huxley quality, he placed his gentle veto on the proposition

and thus

saved the "enemy" the mortification of having to do so.Darwin is

buried in Westminster

Abbey, but this was not to be the final resting-place of the dust of

Mill,

Tyndall, Spencer, George Eliot or Huxley. These had all stood in the

fore of

the fight against superstition and had both given and received blows. The Pantheon of

such

battle-scarred heroes was to be the hearts of those who prize above all

that

earth can bestow the benison of the God within. "Above all else, let me

preserve my integrity of intellect," said Huxley. Here is Huxley's

letter

to Spencer: 4

Marlborough

Place, Dec. 27,

1880 My Dear

Spencer: Your telegram

which reached me on Friday evening caused me great perplexity, inasmuch

as I

had just been talking to Morley, and agreeing with him that the

proposal for a

funeral in Westminster Abbey had a very questionable look to us, who

desired

nothing so much as that peace and honor should attend George Eliot to

her

grave. It can hardly

be doubted that the

proposal will be bitterly opposed, possibly (as happened in Mill's case

with

less provocation) with the raking up of past histories, about which the

opinion

even of those who have least the desire or the right to be pharisaical

is

strongly divided, and which had better be forgotten. With respect to

putting pressure

on the Dean of Westminster, I have to consider that he has some

confidence in

me, and before asking him to do something for which he is pretty sure

to be

violently assailed, I have to ask myself whether I really think it a

right

thing for a man in his position to do. Now I can not

say I do. However

much I may lament the circumstance, Westminster Abbey is a Christian

Church and

not a Pantheon, and the Dean thereof is officially a Christian priest,

and we

ask him to bestow exceptional Christian honors by this burial in the

Abbey.

George Eliot is known not only as a great writer, but as a person whose

life

and opinions were in notorious antagonism to Christian practise in

regard to

marriage, and Christian theory in regard to dogma. How am I to tell the

Dean

that I think he ought to read over the body of a person who did not

repent of

what the Church considers mortal sin, a service not one solitary

proposition of

which she would have accepted for truth while she was alive? How am I

to urge

him to do that which, if I were in his place, I should most

emphatically refuse

to do? You tell me that Mrs. Cross wished for the funeral in the Abbey.

While I

desire to entertain the greatest respect for her wishes, I am very

sorry to

hear it. I do not understand the feeling which could create such a

desire on

any personal grounds, save those of affection, and the natural yearning

to be

near, even in death, those whom we have loved. And on public grounds

the wish

is still less intelligible to me. One can not eat one's cake and have

it too.

Those who elect to be free in thought and deed must not hanker after

the

rewards, if they are to be so called, which the world offers to those

who put

up with its fetters. Thus, however I

look at the

proposal, it seems to me to be a profound mistake, and I can have

nothing to do

with it. I shall be deeply grieved if this resolution is ascribed to

any other

motives than those which I have set forth at greater length than I

intended. Ever

yours very

faithfully, T. H.

HUXLEY |