| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2018 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Little Journeys To the Homes of Great Scientists Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

|

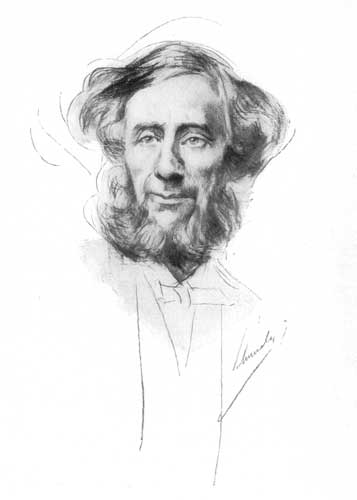

JOHN

TYNDALL

— John Tyndall JOHN

TYNDALL

yndall was of

high descent and lowly birth. His father was a member of

the Irish Constabulary, and there were intervals when the boy's mother

took in

washing. But back of this the constable swore i' faith, when the ale

was right,

that he was descended from an Irish King, and probably this is true,

for most

Irishmen are, and acknowledge it themselves. yndall was of

high descent and lowly birth. His father was a member of

the Irish Constabulary, and there were intervals when the boy's mother

took in

washing. But back of this the constable swore i' faith, when the ale

was right,

that he was descended from an Irish King, and probably this is true,

for most

Irishmen are, and acknowledge it themselves.The father of

our Tyndall spelled

his name Tyndale, and traced a direct relationship to William Tyndale,

who

declared he would place a copy of the English Bible in the hands of

every

plowboy in the British Isles, and pretty nearly made good his vow.

William

Tyndale paid for his privileges, however. He was arrested, given an

opportunity

to run away, but wouldn't; then he was exiled. Finally he was

incarcerated in a

dungeon of the Castle Vilvoorden. His cell was

beneath the level of

the ground, so was cold and damp and dark. He petitioned the governor

of the

prison for a coat to keep him warm and a candle by which he could read.

"We'll give you both light and heat, pretty soon," was the reply. And they did.

They led Tyndale

out under the blue sky and tied him to a stake set in the ground.

Around his

feet they piled brush, and also all of his books and papers that they

could

find. A chain was put

around his neck

and hooked tight to the post. Then the fagots were piled high, and the

fire was

lighted. "He was not

burned to

death," argued one of the priests who was present; "he was not burned

to death. He just drew up his feet and hanged himself in the chain, and

so was

choked: he was that stubborn!" The father of John Tyndall was an

Orangeman

and had in a glass case a bit of the flag carried at the Battle of the

Boyne. It is believed,

with reason, that

the original flag had in it about ten thousand square yards of

material.

Tyndale the Orangeman was of so uncompromising a type that he

occasionally

arrested Catholics on general principles, like the Irishman who beat

the Jew

under the mistaken idea that he had something to do with crucifying

"Our

Savior." "But that was two thousand years ago," protested the

Jew. "Niver moind; I just heard av it — take that and that!" Zeal not wisely

directed is a

true Irish trait. It will not do to say that the Irish have a monopoly

on

stupidity, yet there have been times when I thought they nearly

cornered the

market. I once had charge of a gang of green Irishmen at a lumber-camp. I started a

night-school for

their benefit, as their schooling had stopped at subtraction. One

evening they

got it into their heads that I was an atheist. Things began to come my

way. I

concluded discretion was the better part of valor, and so took to the

woods,

literally. They followed me for a mile, and then gave up the chase. On

the way

home they met a man who spoke ill of me, and they fell upon him and

nearly

pounded his life out. I never had to

lick any of my

gang: they looked after this themselves. On pay-nights they all got

drunk and

fell upon each other — broken noses and black eyes were quite popular.

Father

Driscoll used to come around nearly every month and have them all sign

the

pledge. That story

about the Irishman who

ate the rind of the watermelon "and threw the inside away," is true.

That is just what the Irish do. Very often they are not able to

distinguish

good from bad, kindness from wrong, love from hate. Ireland has all the

freedom

she can use or deserves, just as we all have. What would Ireland do

with

freedom if she had it? Hate for England keeps peace at home. Home rule

would

mean home rough-house — and a most beautiful argument it would be,

enforced

with shillalah logic. The spirit of Donnybrook Fair is there today as

much as

ever, and wherever you see a head, hit it, would be home rule.

Donnybrook is a

condition of mind. If England

really had a grudge

against Ireland and wanted to get even, she could not do better than to

set her

adrift. But then the

Irish impulsiveness

sometimes leads to good, else how could we account for such men as

O'Connor,

Parnell, John Tyndall, Burke, Goldsmith, Sheridan, Arthur Wellesley and

all the

other Irish poets, orators and thinkers who have made us vibrate with

our kind? Transplanted

weeds produce our

finest flowers. The parents of

Tyndall were

intent on giving their boy an education. And to them, the act of

committing

things to memory was education. William Tyndale gave the Bible to the

people;

John Tyndall would force it upon them. The "Book of Martyrs," the

sermons of Jeremy Taylor, and the Bible, little John came to know by

heart. And

he grew to have a fine distaste for all. Once, when nearly a man grown,

he had

the temerity to argue with his father that the Bible might be better

appreciated, if a penalty were not placed upon disbelief in its divine

origin.

A cuff on the ear was the answer, and John was given until sundown to

apologize. He did not apologize. And young

Tyndale then vowed he

would change his name to Tyndall and forever separate himself from a

person

whose religion was so largely mixed with brutality. But yet John

Tyndale was

not a bad man. He had intellect far above the average of his neighbors.

He had

the courage of his convictions. His son had the courage of his lack of

convictions. And the early

drilling in the

Bible was a good thing for young Tyndall. Bible legend and allusion

color the

English language, and any man who does not know his Bible well, can

never hope

to speak or write English with grace and fluency. Tyndall always knew

and

acknowledged his indebtedness to his parents, and he also knew that his

salvation depended upon getting away from and beyond the narrow

confines of

their beliefs and habits. Because a thing helps you in a certain period

of your

education is no reason why you should feed upon it forevermore. This way lies

arrested

development. Life, like

heat, is a mode of

motion, and progress consists in discarding a good thing as soon as you

have

found a better.  ccasionally

Herbert Spencer used to spend a Sunday afternoon with the

Carlyles at their modest home in Chelsea. At such times Jeannie Welsh

would

usually manage to pilot the conversational craft along smooth waters;

but if

she were not present, hot arguments would follow, and finally a point

would be

reached where Carlyle and Spencer would simply sit and glare at each

other. ccasionally

Herbert Spencer used to spend a Sunday afternoon with the

Carlyles at their modest home in Chelsea. At such times Jeannie Welsh

would

usually manage to pilot the conversational craft along smooth waters;

but if

she were not present, hot arguments would follow, and finally a point

would be

reached where Carlyle and Spencer would simply sit and glare at each

other."After such

scenes I always

thought less of two persons, Carlyle and myself," said Spencer; "and

so for many years I very cautiously avoided Cheyne Row." Then there was

another man Spencer avoided, although for a different reason; this

individual

was John Tyndall. On the death of

Tyndall, Spencer

wrote: "There has just

died the

greatest teacher of modern times: a man who stimulated thought in old

and

young, every one he met, as no one else I ever knew did. Once we went

together

for a much-needed rest to the Lake District. Gossip, which has its

advantages

in that it can be carried on with no tax on one's intellectual powers,

had no

part in our conversation. The discussion of great themes began at once

wherever

Tyndall was. "The atmosphere

of the man

was intensely stimulating: everybody seemed to become great and wise

and good

in his presence. "We walked on

the shores of

Windermere, climbed Rydal Mount, rowed across Lake Grasmere (leaving

our names

on the visitors' list), and all the time we dwelt upon high Olympus and

talked. "But, alas!

Tyndall's

vivacity undid me: two days of his company, with two sleepless nights,

and I

fled him as I would a pestilence." But Carlyle

growled out one thing

in Spencer's presence which Spencer often quoted. "If I had my own

way," said Carlyle, "I would send the sons of poor men to college,

and the sons of rich men I would set to work." Manual labor in

right proportion

means mental development. Too much hoe may slant the brow, but hoe in

proper

proportion develops the cerebellum. In the past we

have had one set

of men do all the work, and another set had all the culture: one hoes

and

another thirsts. There are whole areas of brain-cells which are evolved

only

through the efforts of hand and eye, for it is the mind at last that

directs

all our energies. The development of brain and body go together —

manual work

is brain-work. Too much brain-work is just as bad as too much toil; the

misuse

of the pen carries just as severe a penalty as the misuse of the hoe.

And it is

a great satisfaction to realize that the thinking world has reached a

point

where these propositions do not have to be proven. There was a

time when Spencer

regretted that he had not been sent to college, instead of being set to

work.

But later he came to regard his experience as a practical engineer and

surveyor

as a very precious and necessary part of his education. John Tyndall

and Alfred Russel

Wallace had an experience almost identical. In childhood John attended

the

village school for six months of the year, and the rest of the time

helped his

parents, as children of poor people do. When nineteen he went to work

carrying

a chain in a surveying corps. Steady attention to the business in hand

brought

its sure reward, and in a few years he had charge of the squad, and was

given

the duty of making maps and working out complex calculations in

engineering. In mathematics

he especially

excelled. Five years in the employ of the Irish Ordnance Survey and

three years

in practical railroad-building, and Tyndall got the Socialistic bee in

his

bonnet. He resigned a good position to take part in bringing about the

millennium. That he helped

the old world

along toward the ideal there is no doubt; but Tyndall is dead and

Jerusalem is

not yet. When the rule of the barons was broken, and the stage of

individualism

or competition was ushered in, men said, "Lo! The time is at hand and

now

is." But it was not. Socialism is coming, by slow degrees,

imperceptibly

almost as the growing of Spring flowers that push their way from the

damp, dark

earth into the sunlight. And after Socialism, what? Perhaps the

millennium will

still be a long way off. In Eighteen

Hundred Forty-seven,

when Tyndall was twenty-seven years old, Robert Owen, one of the

greatest

practical men the world has ever seen, cried aloud, "The time is at

hand!" Owen was an

enthusiast: all great

men are. He had risen from the ranks by the absolute force of his great

untiring,

restless and loving spirit. From a day laborer in a cotton-mill he had

become

principal owner of a plant that supported five thousand people. Owen saw the

difference between

joyless labor and joyful work. His mills were cleanly, orderly,

sanitary, and

surrounded with lawns, trees and shrubbery. He was the first man in

England to

establish kindergartens, and this he did at his own expense for the

benefit of

his helpers. He established libraries, clubs, swimming-pools,

night-schools,

lecture-courses. And all this time his business prospered. To the average

man it is a

miracle how any one individual could bear the heaviest business burdens

and

still do what Robert Owen did. Robert Owen had

vitality plus: he

was a gourmet for work. William Morris was just such a man, only with a

bias

for art; but both Owen and Morris had the intensity and impetus which

get the

thing done while common folks are thinking about it. Owen was

familiar with every

detail of his vast business, and he was an expert in finance. Like

Napoleon he

said: "The finances? I will arrange them." Robert Owen

erected schoolhouses,

laid out gardens, built mills, constructed tenements, traveled,

lectured, and

wrote books. His enthusiasm was contagious. He was never sick — he

could not

spare the time — and a doctor once said, "If Robert Owen ever dies, it

will be through too much Robert Owen." Owen went over

to Dublin on one

of his tours, and lectured on the ideal life, which to him was

Socialism,

"each for all and all for each." Fourier, the

dreamer, supplied a

good deal of the argument, but Robert Owen did the thing. Socialism

always

catches these two classes, doers and dreamers, workers and drones,

honest men

and rogues, those with a desire to give and those with a lust to get. Among others

who heard Owen speak

at Dublin was the young Irish engineer, John Tyndall. Tyndall was the

type of

man that must be common before we can have Socialism. There was not a

lazy hair

in his head; aye, nor a selfish one, either. He had a tender heart, a

receptive

brain and the spirit of obedience, the spirit that gives all without

counting

the cost, the spirit that harkens to the God within. And need I say

that the

person who gives all, gets all! The economics of God are very simple:

We

receive only that which we give. The only love we keep is the love we

give

away. These are very

old truths — I did

not discover nor invent them — they are not covered by copyright: "Cast

thy bread upon the waters." John Tyndall

was melted by Owen's

passionate appeal of each for all and all for each. To live for

humanity seemed

the one desirable thing. His loving Irish heart was melted. He sought

Owen out

at his hotel, and they talked, talked till three o'clock in the morning. Owen was a

judge of men; his

success depended upon this one thing, as that of every successful

business

must. He saw that Tyndall was a rare soul and nearly fulfilled his

definition

of a gentleman. Tyndall had hope, faith and splendid courage; but best

of all,

he had that hunger for truth which classes him forever among the sacred

few. During his work

out of doors on

surveying trips he had studied the strata; gotten on good terms with

birds,

bugs and bees; he knew the flowers and weeds, and loved all the animate

things

of Nature, so that he recognized their kinship to himself, and he

hesitated to

kill or destroy. Education is a

matter of desire,

and a man like Tyndall is getting an education wherever he is. All is

grist

that comes to his mill. Robert Owen had

but recently

started "Queenswood College" in Hampshire, and nothing would do but

Tyndall should go there as a teacher of science. "Is he a

skilled and

educated teacher?" some one asked Owen. "Better than that,"

replied Owen; "he is a regular firebrand of enthusiasm." And so Tyndall

resigned his

position with the railroad and moved over to England, taking up his

home at

"Harmony Hall." Harmony Hall

was a beautiful

brick building with the letters C. M. carved on the cornerstone in

recognition

of the Commencement of the Millennium. The pupils were mostly workers

in the

Owen mills who had shown some special aptitude for education. The

pupils and

teachers all worked at manual labor a certain number of hours daily.

There was

a delightful feeling of comradeship about the institution. Tyndall was

happy in

his work. He gave

lectures on everything,

and taught the things that no one else could teach, and of course he

got more

out of the lessons than any of the scholars. But after a few

months'

experience with the ideal life, Tyndall had commonsense enough to see

that

Harmony Hall, instead of being the spontaneous expression of the people

who

shared its blessings, was really a charity maintained by one Robert

Owen. It

was a beneficent autocracy, a sample of one-man power, beautifully

expressed. Robert Owen

planned it, built it,

directed it and made good any financial deficit. Instead of Socialism

it was a

kindly despotism. A few of the scholars did their level best to help

themselves

and help the place, but the rest didn't think and didn't care. They

were

passengers who enjoyed the cushioned seats. A few, while partaking of

the

privileges of the place, denounced it. "You can not

educate people

who do not want to be educated," said Tyndall. The value of an

education

lies in the struggle to get it. Do too much for people, and they will

do

nothing for themselves. Many of the

students at Harmony

Hall had been sent there by Owen, because he, in the greatness of his

heart and

the blindness of his zeal, thought they needed education. They may have

needed

it; but they did not want it: ease was their aim. The

indifference and ingratitude

Robert Owen met with did not discourage him: it only gave him an

occasional

pause. He thought that the bad example of English society was too close

to his

experiments: it vitiated the atmosphere. So he came over

to America and

founded the town of New Harmony, Indiana. The fine solid buildings he

erected

in Posey County, then a wilderness, are still there. As for the most

romantic and

interesting history of New Harmony, Robert Owen and his socialistic

experiments,

I must refer the gentle reader to the Encyclopedia Britannica, a work I

have

found very useful in the course of making my original researches. After a year at

Harmony Hall,

Tyndall saw that he would have to get out or else become a victim of

arrested

development, through too much acceptance of a strong man's bounty. "You

can not afford to accept anything for nothing," he said. Life at

Harmony

Hall to him was very much like life in a monastery, to which stricken

men flee

when the old world seems too much for them. "When all the people live

the

ideal life, I'll live it; but until then I'm only one of the great many

strugglers." Besides, he felt that in missing university training he

had

dropped something out of his life. Now he would go to Germany and see

for

himself what he had missed. While

railroading he had saved up

nearly four hundred pounds. This money he had offered at one time to

invest in

shares in the Owen mills. But Robert Owen said, "Wait two years and

then

see how you feel!" Robert Owen was

not a financial

exploiter. Tyndall may have differed with him in a philosophic way; but

they

never ceased to honor and respect each other. And so John

Tyndall bade the

ideal life good-by, and went out into the stress, strife and struggle,

resolved

to spend his two thousand dollars in bettering his education, and then

to start

life anew.  obert Owen had

been over to America and had met Emerson, and very

naturally caught it. When he returned home he gave young Tyndall a copy

of

Emerson's first book, the "Essay on Nature," published anonymously. obert Owen had

been over to America and had met Emerson, and very

naturally caught it. When he returned home he gave young Tyndall a copy

of

Emerson's first book, the "Essay on Nature," published anonymously.Tyndall read

and re-read the

book, and read it aloud to others and spoke of it as a "message from

the

gods." He also read

every word that

Carlyle put in print. It was Carlyle who introduced him to German

philosophy

and German literature, and fired him with a desire to see for himself

what

Germany was doing. Germany had

still another mystic

tie that drew him thitherward. It was at Marburg, Germany, that his

illustrious

namesake had published his translation of the Bible. At Marburg

there was a

University, small, 't was true, but its simplicity and the cheapness of

living

there were recommendations. So to Marburg he went. Tyndall found

lodgings in a

little street called "Heretics' Row." Possibly there be people who

think that Tyndall's taking a room in such a street was chance, too.

Chance is

natural law not understood. Marburg is a

very lovely little

town that clings amid a forest of trees to the rocky hillside

overlooking the

River Lahn. Tyndall was very happy at Marburg, and at times very

miserable. The

beauty of the place appealed to him. He was a climber by nature, and

the hills

were a continual temptation. But the

language was new; and

before this his work had all been of a practical kind. College seems

small and

trivial after you have been in the actual world of affairs. But Tyndall

did not

give up. He rose every morning at six, took his cold bath, dressed and

ran up

the hill half a mile and back. He breakfasted with the family, that he

might

talk German. Then he dived into differential calculus and philosophical

abstrusities. He was not sent to college: he went. And he made college

give up

all it had. On the wall of his room, as a sort of ornamental frieze in

charcoal, he wrote this from Emerson: "High knowledge and great

strength

are within the reach of every man who unflinchingly enacts his best." Down in the

town was a bronze

bust of a man who wrote for it the following inscription: "This is the

face of a man who has struggled energetically." One might

almost imagine that

Hawthorne had received from Tyndall the hint which evolved itself into

that

fine story, "The Great Stone Face." The bust just

mentioned,

attracted John Tyndall for another reason: Carlyle had written of the

man it

symboled: "Reader, to thee, thyself, even now, he has one counsel to

give,

the secret of his whole poetic alchemy. Think of living! Thy life, wert

thou

the pitifullest of all the sons of earth, is no idle dream, but a

solemn

reality. It is thine own; it is all thou hast with which to front

eternity.

Work, then, even as he has done — like a star, unhasting and unresting."  t Marburg,

Tyndall was on good terms with the great Bunsen, and used to

act as his assistant in making practical chemical experiments before

his

classes. t Marburg,

Tyndall was on good terms with the great Bunsen, and used to

act as his assistant in making practical chemical experiments before

his

classes.These amazing

things done by

chemists in public are seldom of much value beyond giving a thrill to

visitors

who would otherwise drowse; it is like humor in an oration: it opens up

the

mental pores. Alexander

Humboldt once attended

a Bunsen lecture at Marburg and complimented Tyndall by saying, "When I

take up sleight-of-hand work, consider yourself engaged as my first

helper." Tyndall's way of standing with his back to the audience,

shutting

off the view of Bunsen's hands while he was getting ready to make an

artificial

peal of thunder, made Humboldt laugh heartily. Humboldt

thought so well of the

young man who spoke German with an Irish accent, that he presented him

with an

inscribed copy of one of his books. The volume was a most valuable one,

for

Humboldt published only in deluxe, limited editions, and Tyndall was so

overcome that all he could say was, "I'll do as much for you some

day." Not long after this, through loaning money to a fellow student,

Tyndall found himself sadly in need of funds, and borrowed two pounds

on the

book from an 'Ebrew Jew. That night, he

dreamed that

Humboldt found the volume in a secondhand store. In the morning,

Tyndall was

waiting for the pawnbroker to open his shop to get the book back ere

the

offense was discovered. Heinrich Heine

once inscribed a

volume of his poems to a friend, and afterward discovered the volume on

the

counter of a secondhand dealer. He thereupon haggled with the bookman,

bought

the book and beneath his first inscription wrote, "With the renewed

regards of H. Heine." He then sent the volume for the second time to

his

friend. 'T is possible that Tyndall had heard of this. In Eighteen

Hundred Fifty, when

Tyndall was thirty years of age, he visited London, and of course went

to the

British Institution. There he met Faraday for the first time and was

welcomed

by him. The British

Institution consists

of a laboratory, a museum and a lecture-hall, and its object is

scientific

research. It began in a very simple way in one room and now occupies

several

buildings. It was founded

by Benjamin

Thompson, an American, and so it was but proper that its sister

concern, the

Smithsonian Institution, should have been founded by an Englishman. Sir Humphry

Davy on being asked,

"What is your greatest discovery?" replied, "Michael

Faraday." But this was a mere pleasantry, the truth being that it was

Michael Faraday who discovered Sir Humphry Davy. Faraday was a

bookbinder's

apprentice, a fact that should interest all good Roycrofters. Evenings, when

Sir Humphry Davy

lectured at the British Institution, the young bookbinder was there.

After the

lecture he would go home and write out what he had heard, with a few

ideas of

his own added. For be it known, taking notes at a lecture is a bad

habit — good

reporters carry no notebooks. After a year

Faraday sent a

bundle of his impressions and criticisms to Sir Humphry Davy

anonymously. Great

men seldom read manuscript that is sent to them unless it refers to

themselves.

At the next lecture, Sir Humphry began by reading from Faraday's notes,

and

begged that if the writer were present, he would make himself known at

the

close of the address. From this was

to ripen a love

like that of father and son. Every man who builds up such a work as did

Sir

Humphry Davy is appalled, when he finds Time furrowing his face and

whitening

his hair, to think how few indeed there are who can step in and carry

his work

on after he is gone. The love of

Davy for the young

bookbinder was almost feverish: he clutched at this bright,

impressionable and

intent young man who entered so into the heart and soul of science;

nothing

would do but he must become his assistant. "Give up all and follow

me!" And Faraday did. Something of

the same feeling

must have swept over Faraday after his work of twenty-five years as

director of

the British Institution, when John Tyndall appeared, tall, thin,

bronzed,

animated, quoting Bunsen and Humboldt with an Irish accent. And so in time Tyndall became assistant to Faraday, then lecturer in natural history; and when Faraday died, Tyndall, by popular acclaim, was made Fullerian Lecturer and took Faraday's place. This was to be his life-work, and it so placed him before the world that all he said or did had a wide significance and an extended influence.  yndall was

always a most intrepid mountain-climber.

The Alps lured him like the song of the Lorelei, and the wonder was

that his

body was not left in some mountain crevasse, "the most beautiful and

poetic of all burials," he once said. yndall was

always a most intrepid mountain-climber.

The Alps lured him like the song of the Lorelei, and the wonder was

that his

body was not left in some mountain crevasse, "the most beautiful and

poetic of all burials," he once said.But for him

this was not to be,

for Fate is fond of irony. The only man who ever braved the full

dangers of the

Grand Canyon of the Colorado was killed by a suburban train in Chicago

while on

his wedding-tour. Most bad men die in bed, tenderly cared for by

trained nurses

in white caps and big aprons. Tyndall climbed

to the summit of

the Matterhorn, ascended the so-called inaccessible peak of the

Weisshorn,

scaled Mont Blanc three times, and once was caught in an avalanche,

riding

toward death at the rate of a mile a minute. Yet he passed away from an

overdose, or a wrong dose, of medicine given him through mistake, by

the hands

of the woman he loved most. At one time

Tyndall attempted to

swim a mountain-torrent; the stream, as if angry at his Irish

assurance, tossed

him against the rocks, brought him back in fierce eddies, and again and

again

threw him against a solid face of stone. When he was rescued he was a

mass of

bruises, but fortunately no bones were broken. It was some days before

he could

get out, and in his sorry plight, bandaged so his face was scarcely

visible,

Spencer found him. "Herbert, do you believe in the actuality of

matter?" was John's first question. Both Tyndall

and Huxley made

application to the University of Toronto for positions as teachers of

science;

but Toronto looked askance, as all pioneer people do, at men whose

college

careers have been mostly confined to giving college absent treatment. Herbert Spencer

avowed again and

again that Tyndall was the greatest teacher he ever knew or heard of,

inspiring

the pupil to discover for himself, to do, to become, rather than

imparting

prosy facts of doubtful pith and moment. But Herbert Spencer, not being

eligible to join a university club himself, was possibly not competent

to

judge. Anyway, England

was not so

finical as Canada, and so she gained what Canada lost.  yndall paid a

visit to the United States in the year Eighteen Hundred

Seventy-two, and lectured in most of the principal cities, and at all

the great

colleges. He was a most fascinating speaker, fluent, direct, easy, and

his

whole discourse was well seasoned with humor. yndall paid a

visit to the United States in the year Eighteen Hundred

Seventy-two, and lectured in most of the principal cities, and at all

the great

colleges. He was a most fascinating speaker, fluent, direct, easy, and

his

whole discourse was well seasoned with humor.Whenever he

spoke, the auditorium

was taxed to its utmost, and his reception was very cordial, even in

colleges

that were considered exceedingly orthodox. Possibly, some

good people who

invited him to speak did not know it was loaded; and so his earnest

words in

praise of Darwin and the doctrine of evolution, occasionally came like

unto a

rumble of his own artificial thunder. "I speak what I think is truth;

but

of course, when I express ungracious facts I try to do so in what will

be

regarded as not a nasty manner," said Tyndall, thus using that pet

English

word in a rather pleasing way. In his

statement that the prayer

of persistent effort is the only prayer that is ever answered, he met

with a

direct challenge at Oberlin. This gave rise to what, at the time,

created quite

a dust in the theological road, and evolved "The Tyndall Prayer

Test." Tyndall

proposed that one hundred

clergymen be delegated to pray for the patients in any certain ward of

Bellevue

Hospital. If, after a year's trial, there was a marked decrease in

mortality in

that ward, as compared with previous records, we might then conclude

that

prayer was efficacious, otherwise not. One good

clergyman in Pittsburgh

offered publicly to debate "Darwinism" with Tyndall, but beyond a

little scattered shrapnel of this sort, the lecture-tour was a great

success.

It netted just thirteen thousand dollars, the whole amount of which

Tyndall

generously donated as a fund to be used for the advancement of natural

science

in America. In Eighteen

Hundred Eighty-five,

this fund had increased to thirty-two thousand dollars, and was divided

into

three equal parts and presented to Columbia, Harvard and the University

of

Pennsylvania. The fund was still further increased by others who

followed

Professor Tyndall's example, and Columbia, from her share of the

Tyndall fund,

I am told now supports two foreign scholarships for the benefit of

students who

show a special aptitude in scientific research. Professor James of

Harvard once

said: "The impetus to popular scientific study caused by Professor

Tyndall's lectures in the United States was most helpful and fortunate.

Speaking but for myself, I know I am a different man and a better man,

for

having heard and known John Tyndall."  hen John

Tyndall died, in the year Eighteen Hundred Ninety-three,

Spencer wrote: hen John

Tyndall died, in the year Eighteen Hundred Ninety-three,

Spencer wrote:"It never

occurred to

Tyndall to ask what it was politic to say, but simply to ask what was

true. The

like has of late years been shown in his utterances concerning

political

matters — shown, it may be, with too great frankness. This extreme

frankness

was displayed also in private, and sometimes, perhaps, too much

displayed; but

every one must have the defects of his qualities. Where absolute

sincerity

exists, it is certain now and then to cause an expression of a feeling

or

opinion not adequately restrained. "But the

contrast in

genuineness between him and the average citizen was very conspicuous.

In a

community of Tyndalls (to make a rather wild supposition), there would

be none

of that flabbiness characterizing current thought and action — no

throwing

overboard of principles elaborated by painful experience in the past,

and

adoption of a hand-to-mouth policy unguided by any principle. He was

not the

kind of man who would have voted for a bill or a clause which he

secretly

believed would be injurious, out of what is euphemistically called

'party

loyalty,' or would have endeavored to bribe each section of the

electorate by

'ad captandum' measures, or would have hesitated to protect life and

property

for fear of losing votes. What he saw right to do he would have done,

regardless of proximate consequences. "The ordinary

tests of

generosity are very defective. As rightly measured, generosity is great

in

proportion to the amount of self-denial entailed; and where ample means

are

possessed, large gifts often entail no self-denial. Far more

self-denial may be

involved in the performance, on another's behalf, of some act that

requires

time and labor. In addition to generosity under its ordinary form,

which

Professor Tyndall displayed in unusual degree, he displayed it under a

less

common form. "He was ready

to take much

trouble to help friends. I have had personal experience of this. Though

he had

always in hand some investigation of great interest to him, and though,

as I

have heard him say, when he bent his mind to the subject he could not

with any

facility break off and resume it again, yet, when I have sought

scientific aid,

information or critical opinion, I never found the slightest reluctance

to give

me his undivided attention. Much more markedly, however, was this kind

of

generosity shown in another direction. Many men, while they are eager

for

appreciation, manifest little or no appreciation of others, and still

less go

out of their way to express it. "With Tyndall

it was not

thus; he was eager to recognize achievement. Notably in the case of

Michael

Faraday, and less notably, though still conspicuously in many cases, he

has

bestowed much labor and sacrificed many weeks in setting forth the

merits of

others. It was evidently a pleasure to him to dilate on the claims of

fellow

workers. "But there was

a derivative

form of this generosity calling for still greater eulogy. He was not

content

with expressing appreciation of those whose merits were recognized, but

he used

energy unsparingly in drawing the attention of the public to those

whose merits

were unrecognized; time after time in championing the cause of such, he

was

regardless of the antagonism he aroused and the evil he brought upon

himself.

This chivalrous defense of the neglected and ill-used has been, I think

by few,

if any, so often repeated. I have myself more than once benefited by

his

determination, quite spontaneously shown, that justice should be done

in the

apportionment of credit; and I have with admiration watched like

actions of his

in other cases: cases in which no consideration of nationality or of

creed

interfered in the least with his insistence on equitable distribution

of

honors. "In this

undertaking to

fight for those who were unfairly dealt with, he displayed in another

direction

that very conspicuous trait which, as displayed in his Alpine feats,

has made

him to many persons chiefly known: I mean courage, passing very often

into

daring. And here let me, in closing this little sketch, indicate

certain

mischiefs which this trait brought upon him. Courage grows by success.

The

demonstrated ability to deal with dangers produces readiness to meet

more

dangers, and is self-justifying where the muscular power and the nerve

habitually prove adequate. But the resulting habit of mind is apt to

influence

conduct in other spheres, where muscular power and nerve are of no

avail — is

apt to cause the daring of dangers which are not to be met by strength

of limb

or by skill. Nature as externally presented by precipice ice-slopes and

crevasses may be dared by one who is adequately endowed; but Nature, as

internally represented in the form of physical constitution, may not be

thus

dared with impunity. Prompted by high motives, John Tyndall tended too

much to

disregard the protests of his body. "Over-application

in Germany

caused absolute sleeplessness, at one time, I think he told me, for

more than a

week; and this, with kindred transgressions, brought on that insomnia

by which

his after-life was troubled, and by which his power for work was

diminished;

for, as I have heard him say, a sound night's sleep was followed by a

marked

exaltation of faculty. "And then, in

later life,

came the daring which, by its results, brought his active career to a

close. He

conscientiously desired to fulfil an engagement to lecture at the

British

Institution, and was not deterred by fear of consequences. "He gave the

lecture, notwithstanding

the protest which for days before his system had been making. The

result was a

serious illness, threatening, as he thought at one time, a fatal

result; and

notwithstanding a year's furlough for the recovery of health, he was

eventually

obliged to resign his position. But for this defiance of Nature, there

might

have been many more years of scientific exploration, pleasurable to

himself and

beneficial to others; and he might have escaped that invalid life which

for a

long time he had to bear. In his case, however, the penalties of

invalid life

had great mitigations — mitigations such as fall to the lot of few. "It is

conceivable that the

physical discomforts and mental weariness which ill-health brings may

be

almost, if not quite, compensated by the pleasurable emotions caused by

unflagging attentions and sympathetic companionship. If this ever

happens, it

happened in his case. All who have known the household during these

years of

nursing are aware of the unmeasured kindness he has received without

ceasing. I

happen to have had special evidence of this devotion on the one side

and

gratitude on the other, which I do not think I am called upon to keep

to

myself, but rather to do the contrary. In a letter I received from him

some

half-dozen years ago, referring, among other things, to Mrs. Tyndall's

self-sacrificing care of him, occurred this sentence: 'She has raised

my ideal

of the possibilities of human nature.'" |