| Web

and Book

design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2009 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

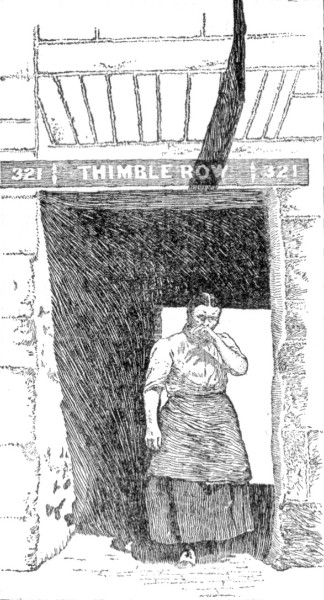

V

HISTORIC GROUND  Entrance to a Close MIDSUMMER had come and passed, and there were hints of autumn in the bare mowing-fields, and in an occasional chill night. The rowan trees in the dens were beginning to get gay with their clusters of scarlet berries, the moors were taking on a pink cast with the first opening of the heather buds, bluebells nodded by every pathside, and the wild rosebushes, whose riotous tangles, when I first came, were profusely adorned with bloom, had dropped their petals and were now dotted over with green hips. So, too, the hawthorn hedges which had been in their fulness of frosty white two months before were now loaded with tiny haws. It was at this time that I took my final leave of Drumtochty, intending to proceed more or less directly to Edinburgh. But I was in no haste, and most of the first day I spent in getting better acquainted with Perth and its vicinity. Like all Scotch towns, Perth is very much crowded in its poorer parts, and many curious little passageways dive in among the shops that front on the chief streets to the huddles of dwellings in behind. These passages are miniature tunnels, and above each narrow entering arch a name is painted — such and such a "close." If I went on through, I soon came on a small paved open, hedged about with old stone houses, though once in a while a close took more public character by having in its semi-seclusion an inn, or two or three small shops. The people swarmed in these humbler neighborhoods, and slovenly women and dirty, half-clad children were everywhere. Among other street scenes I recall a tattered old woman talking with some men and smoking a stub of a pipe. She would take out the pipe every now and then, and spit on the pavement just like a veteran male tobacco-user. Another picturesque remembrance of the city has to do with a park on its borders known as the North Inch. This park was a great expanse of grass with a few rows of young trees started on it. A number of cows were grazing there, and a scattering of strollers and bicyclers were on the paths; but the main feature of the path was the clothes-poles that stretched away in hundreds for a mile or so. This network of lines was hung full of garments, both of white and gayer colors, and the grass was spread with quantities more, and women with barrows were busy in the midst of this mammoth wash, so that taken all together it suggested, as viewed from afar, some gaudy show in full blast. Children were numerous in the neighborhood of the clothes, many of them babies in their mother's arms or in the care of an older sister. But there were plenty of toddlers, too, and others a trifle more mature, who gave their energies to racing and romping, turning summersaults, and making valorous attempts to stand on their heads. After a noon lunch I took a tram for Scone Palace. This tram was of the usual British type — a clumsy, two-story horse-car, plastered all over with a crazy-patchwork of advertisements. A narrow, winding stair at the rear gave access to the roof, and the novice finds the ascent rather awkward, and the downlook from the top impresses him with an exaggerated idea of the height, and makes him fear the vehicle may overturn from topheaviness. Otherwise the roof is an agreeable place in pleasant weather. Scone proved to be less than a half-hour's ride distant. The palace is a gray, castlelike mansion, reposing in the retirement of an attractive park that extends for several miles along the banks of the river Tay. There are many acres of close-clipped lawns, and trees of all kinds, scattered and in groves, not a few of them so lofty and deep-shadowed as to be suggestive of tropical luxuriance. I saw the palace, but the flag floating from the loftiest tower showed. that its noble resident was at home, and I was only allowed to gaze at a distance. On the present palace grounds, not far from the building itself, was once a village where now a heavy wood rises. The market cross still stands to mark the centre of the ancient hamlet, and the people of the region say, "Many a village has lost its cross, but only one cross has lost its village." The burial-place of this olden-time community is just aside from the main avenue to the palace, and that tiny plot within his grounds the Earl does not own, nor can he shut the public from entering his park on their way to it. This is said to be a sore trial to the dweller in the palace, and it is related that in his younger days he spent £40,000 in a vain attempt to get from the courts the right to close this little cemetery. The first mention of Scone in history dates back eleven centuries, at which time a monastery was built there. The most notable treasure that the holy fathers of the institution had in their care was the stone on which the kings of Scotland were inaugurated. This stone is now in Westminster Abbey, immediately beneath the seat of the chair in which the kings of England are crowned. It is a clumsy, oblong block of dull reddish sandstone, with a few small imbedded pebbles. If its legendary story is to be credited, it was originally the pillow of the patriarch Jacob at Luz, when he dreamed his dream of the ladder to heaven, on which the angels were ascending and descending. Later, about the time of Moses, the stone finds its way into the hands of one Gathelus, son of an Athenian king. This Gathelus became a man of note in Egypt, where he entered the service of Pharaoh. He rose rapidly, and finally married that ruler's daughter Scota. Gathelus was on excellent terms with Moses, who, shortly before the plagues were visited on the land, gave him a friendly hint of what was coming. So impressed was Gathelus with the undesirability of experiencing these plagues, that he took ship and sailed away to Spain. There he acquired a wide kingdom, and there he died. The ancient stone which Jacob had used as a pillow had always been numbered among the dead monarch's most valuable possessions, and he bequeathed it to his son, who took his legacy to Ireland, and by virtue of it established himself as chief ruler of the Isle. He placed the stone on the famous hill of Tara, where it served as the coronation seat of a long succession of Irish kings. Perhaps the most remarkable thing about the stone was that it gave forth a peculiar sound each rime a king sat on it, which intimated its opinion of the new ruler, and this judgment was deemed prophetical of the nature of the reign; but it seems to have lost its power of thus expressing its opinion of fledgling monarchs when it was removed from Tara. The belief was general that wherever was found the stone the Scottish race was certain to rule. Fergus, first king of the Scots in Scotland, carried the stone of mystery with him when he crossed over to that country nearly four hundred years before Christ, and deposited it in the castle of Dunstaffnage, near Oban. In that residence of the early Scotch kings it remained until the year 834, when it was conveyed by Kenneth II to Scone. From then on the history of the stone becomes more authentic. It was placed in the monastery burial-ground. When a coronation took place the stone was covered with cloth of gold, and the king was conducted to it with impressive pomp by the greatest nobles of the realm. Crowds of people gazed on the solemn scene from a near hill known as the Mount of Belief, or vulgarly as "Boot Hill," a title which has a curious legendary explanation. The legend is that when the barons came to be present at a coronation they stood in boots half-filled with earth. Each had brought this soil from his native district that he might take part in the ceremonies standing on his "own land." At the close of the exercises the boots were taken off and emptied, and in process of time these emptyings formed Boot Hill. The "Stone of Destiny" was the visible sign of the Scotch monarchy, and its loss was keenly felt when Edward I of England bore it off to Westminster Abbey. No sooner had Scotland won its freedom, than King Robert Bruce, in concluding the treaty of peace with the English, stipulated that the stone should be restored. But the Londoners rose in a mob to resist the fulfilling of this provision, and the treaty was later abrogated to allow the stone to continue at Westminster. There it was nearly three hundred years afterward, when a purely Scottish prince, James, son of Mary Stuart, ascended the English throne. The two kingdoms then became one, and all parries concerned were as content to have the stone in London as elsewhere. After the day spent at Perth and Scone I travelled eastward to Kinross, on the shores of Loch Leven. I suppose the majority of visitors are drawn to the loch by its fishing, reputed to be the finest in the British Isles, but for me its attraction consisted in the music of its name and its association with Scotch song, story, and history. Of all the nooks and corners into which my rambling in the vicinity of Kinross led me, I liked best a little grove of trees just back from the reedy borders of the lake, not far from the village. It afforded a most agreeable shelter and lounging-place, especially in the cloudy and windy weather that prevailed during my sojourn. The waters were gray and white-capped and the sky was rarely otherwise than dull and threatening, though now and then blue loopholes appeared which let stray patches of sunshine through. Usually a wild duck or two would be in sight, bobbing over the waves with corklike buoyancy. The view was pleasing, but not in any wise striking. Across the lake rose a green, treeless mountain-range, and another fine grassy range lay southward, while the loch itself was dotted with a number of small islands. On the largest of these, five acres in extent, stood the battered ruin of a castle peeping out from among the trees, and imparting a most stirring interest to the scene, for those walls long ago held Mary, Queen of Scots, a prisoner. She was only twenty-five years of age, yet shortly before she had married for the third time. This marriage followed close on the assassination of her second husband, Lord Darnley, in whose death the new consort, the Earl of Bothwell, was believed to be implicated. Civil war resulted, and the queen fell into the hands of her enemies, and was taken to this lonely island in Loch Leven. It was her first real imprisonment, though there had been short periods previously, in her checkered career, when she had been held in restraint scarcely less harassing. The southeastern tower of the castle was set apart for her lodgings, and Lady Douglas was appointed her jailer. Though the queen's followers had been beaten and dispersed in the recent strife, her party was by no means extinct, and the leaders were continually plotting, while they awaited a favorable opportunity to effect her release and restore her to power. Neither the prison walls nor the isolation sufficed to prevent her from keeping in constant secret communication with her friends. She was ably aided in this by her faithful servant, John Beaton, who hovered in disguise near Loch Leven, and never failed to find means of carrying messages to and fro. At length George Douglas, son of the royal prisoner's jailer, became interested in her behalf, and assisted her in arranging a plan of escape with an association of loyal gentlemen who had pledged themselves to break her chains. But before the project could be carried out it was betrayed, and George Douglas was expelled from the castle in disgrace, and forbidden ever to set foot on the island again. Restraints were redoubled; yet it was only a few days later that the queen nearly succeeded in getting away. A laundress was employed who came across the water frequently from Kinross to fetch and carry the linen belonging to her Majesty and her ladies. This laundress consented to assist the queen to regain her freedom. George Douglas, who, though expelled from the castle, remained concealed in the house of a friend at Kinross, was to help also. Until the plans were perfected, Mary pretended to be ill, and passed her mornings in bed, apparently indifferent to everything. But one day, when the laundress came as usual, and went to the queen's room to deliver the clothes she had washed, and tie up and carry away another bundle, Mary slipped out of bed and disguised herself in the woman's humble garments. Then she drew a muffler over her face, took the soiled clothes in her arms, and passed out of the castle to the boat unsuspected. All went well until, midway between the fortress and the shore, one of the rowers, fancying there was something peculiar about the bearing of their passenger, said jokingly to his assistant, Come, let us see what manner of dame this is." Suiting the action to the word he endeavored to pull aside the lady's muffler. She put up her hands to resist, and their whiteness and delicacy made known her identity. She ordered the rowers to go on and take her to the shore, and threatened to punish them if they refused; but they were aware how powerless she was, and instead they rowed back to the island, agreeing, however, not to inform any one of her attempted flight. Soon after this Mary found an effective ally in a boy of sixteen, who acted as page to the lady of the castle. This lad went by the name of Willie Douglas, though among the inmates of the fortress he was oftener spoken of as "Orphan Willie," or "Foundling Willie," from the fact that he had been discovered lying near the castle entrance when an infant, abandoned to the good-will of those within. Willie became a most ardent votary of the captive queen, and he told her that below her tower was a postern gate, through which they sometimes went out in one of the boats on the lake; he would get the boat ready and bring the key of the gate. The boy got word to George Douglas, and a company of armed horsemen concealed themselves in a glen across the water, ready to become an escort for the queen the moment she was liberated. The guards who kept watch night and day at the gates of her Majesty's tower were accustomed to quit their post at half-past seven each evening, long enough to sup with the castle household in the great hall. Meanwhile the five large keys attached to an iron chain were placed beside Sir William Douglas on the table at which he and his mother sat in state. While waiting on the knight and the lady Orphan Willie contrived to drop a napkin over the keys and get them off the table without being detected. Much elated, he ran with them to the queen's tower. Mary knew his plans, and was ready to start as soon as he appeared. She was attired in the clothes of one of her maids, who stayed behind to personate her royal mistress. The queen hurried to the boat, and Willie locked all the gates behind them and threw the keys into the water. Then with all his might he rowed for the opposite shore. The loyal horsemen met them, and they were off into the night. After fourteen months' imprisonment Mary Queen of Scots was free, yet in nearly all the days following she was a fugitive, even until she fell into the hands of Elizabeth of England, and once more was behind prison walls, no more to have liberty save as death on the scaffold released her and ended her troubled, fateful life. From Kinross I went to Edinburgh, the most picturesque and interesting large town in Britain. The ground on which it is built is much wrinkled into hills and valleys, and on a crag that overtops all the rest is the castle. The town's origin is lost in dim antiquity, but no doubt its founders were attracted to the spot by the defensive advantages of the steep isolated castle rock. There they built their clay fort, and then they began tilling the land in the valleys and on the hills neighboring, and when danger threatened, they drove their cattle to the rock. On three sides the eminence drops away almost perpendicularly, but on the fourth side it slopes gently eastward in the form of a narrow ridge, along the top and sides of which a town gradually formed. I had not been long in Edinburgh before I turned my steps castleward, crossed the drawbridge that spans the ancient moat, and dodged along through the guides who blocked the way with offers of their services until I passed under the portcullis-guarded arch of the entrance. As I went in a squad of Scotch soldiers marched jauntily out with their pipes jigging merrily on ahead. The soldiers with their bare knees, their kilts, high black hats, and other fancy fixings, looked more as if they were gotten up for a circus parade than for war, but they were tall, brawny fellows, and I do not question their effectiveness. The castle is to-day mainly composed of heavy, gray stone barracks of no great antiquity, but among the rest is a tiny chapel erected about eight hundred years ago, which claims to date back farther than any other building in Scotland. The sole occupant of the chapel, as I saw it, was an old woman who sat behind an array of guide-books for sale, like a venerable spider in its lair, hopeful of enticing unwary flies. In a room near by one can look through some iron bars at the ancient Scottish crown, sceptre, and other gewgaws of this sort; but there was to me much more charm in the view from the fortification parapets off over the smoky city. The castle stands at the far end of the ridge, where the rock rises highest, and you cannot but think the situation must have possessed almost impregnable strength in the days before the invention of heavy siege pieces. Nothing, too, would seem more unlikely than escape from the dungeon prisons hewn in the solid rock; yet the castle has been often taken, and prisoners have frequently found means to get free. Even the almost vertical cliffs have been scaled on occasions, and it is one of the pleasures of the present-day little boys of Edinburgh to risk their necks in trying to climb the crags.  Edinburgh Close under the base of the hill to the north is a narrow glen. Through the centre of this runs the railway, but the rest is laid out in lawns and flower-beds, with a mingling of shrubbery and trees. Formerly a body of water known as the North Loch filled the hollow. The loch was a great help in affording protection from that direction. To gain something of the same security on the other side a wall was erected. For many centuries the inhabitants huddled their dwellings along the ridge immediately east of the castle, and they were all loath to build outside the city wall, because a house thus exposed was nearly certain to be rifled and burned. Nor was a house inside the walls wholly safe. The town was within easy access from the English borders, and again and again the southern raiders gained entrance and robbed and wrecked the houses as they willed, while the people fled to the castle and to the shelter of the surrounding forests. Edinburgh became the recognized capital of the kingdom after the murder of James I at Perth in 1437. No other city in the realm afforded as great security to the royal household against the designs of the nobles, and thenceforth it was their place of residence. There parliament met, and there were located the mint and various other government offices. Its importance was in this way greatly increased, and it grew more and more densely populated. But the days of feudalism were not yet past, and wars, plottings, and lawlessness abounded. Edinburgh was a centre of this ferment, for which reason the inhabitants were as reluctant as ever to live outside the walls. To gain room they expanded their houses skyward. The town at this period consisted of the original chief thoroughfare called the High Street and a parallel way on the south, narrow and confined, that was known as the Cowgate, and not until the middle of the eighteenth century did the citizens begin to build beyond the limits. The High Street and the Cowgate were connected by scores of narrow cross alleys, or closes. The dwellings seldom contained less than six floors. Often there were ten or twelve floors, and the great height to which the houses towered was the more imposing because they were built on an eminence. "Auld Reekie" is the term applied to this section of the city, and it is grimy enough with the stains of smoke and age to amply merit the name. The sanitary conditions are in many respects those of the fourteenth century, and scores of families are crowded in some of the tall structures. Probably no other city in the kingdom, not even London, has such grewsome rookeries.  Melrose Abbey Frequently the old houses with their thick walls and narrow entrances have the strength of fortresses. They were indeed originally the houses of the aristocracy of the town, who were noted for their intrigues and violence, and with whom a house capable of defence was a matter of some importance. As the city grew and the social conditions of the country became more stable, the gentry abandoned Auld Reekie and built houses in the newer sections of the city, while their former domiciles fell into the hands of the most desperate of the poor. Yet the finer and more modern portion of the town is prosaic and commonplace, while in Auld Reekie you cannot but feel a marvellous attraction in the ancient gray walls and crooked, deep-worn stairways, and the picturesque outthrust of poles from the windows with a few rags of washing fluttering on them, and in the heaps of chimney-pots with their blue curlings of smoke. These old buildings have a sentiment that is never found in new ones — a something akin to human that comes from their long connection with life and its daily labor, its aspirations and its troubles. What stories the old stones could tell if they had speech! What tragedies and dark deeds they must have witnessed! In the summer weather when I wandered among the tall houses, most of the windows were open, and some occupant leaning out over the sill was rarely lacking. The doorways likewise had their loiterers, and the sidewalks and narrow wynds and closes were thickly populated. There were some dreadful-looking creatures to be seen on Auld Reekie's byways. Once I was startled in turning the corner of an alley to find two women fighting. They were barefoot, bareheaded, dishevelled, and hideous. One was old and black-faced, and had some sort of burden gathered up in her apron. The other, who was younger, but hardly less ill-favored, was brandishing her fists in her companion's face and talking hysterically and crying. Finally she knocked the old woman down. But that ancient got up nimbly, and the two indulged in further loud-voiced abuse. Then they separated, and the gathering crowd dispersed. The High Street as it descends the hill from the castle at length merges into the Canongate, and the latter thoroughfare continues the gentle downward course for about a mile to the big, dark-looking pile of Holyrood Palace. A little to one side of the palace is a roofless ruin, all that is left of an abbey built in the year 1128 by King David I and named in honor of the holy cross or rood brought to Scotland a few years previously by St. Margaret. Two centuries later this "black rood of Scotland," as it was called, fell into English hands, and no more is known of it. Thrice the abbey was burned by the southern foe, and a fourth time it was plundered and burned by the mob at the revolution of 1688. For seventy years after that it remained neglected, and when it was finally repaired the roof proved too heavy, and fell in. The abbey has continued a ruin ever since that disaster. The foundations of a palace apart from the abbey were laid in 1503, and Holyrood became the chief seat of the Scottish sovereigns. It is as the residence of the ill-starred Queen Mary that it most stirs the interest of the average visitor. You can see her rooms, and her alleged furniture, including the bed in which she slept, a curious affair with immensely tall posts that hold a canopy aloft high toward the ceiling. Its quilts and draperies are faded now and dropping to pieces, and it is a question whether the bed in its better days was rich and beautiful or overcolored and tawdry. The impression the rooms made on me was that the household comforts of the old kings and queens were not such as to stir much modern envy. When I departed from Edinburgh, it was to go to Stirling, a town curiously like the one I had left, in its physical characteristics, for it is overlooked in the same way by a great castle on the heights of a mountainous crag. The situation, by reason of its defensive strength and its position in the narrowest part of the northern kingdom, makes it the natural key to the Highlands, and it was often assaulted in the quarrels of the clans or besieged in turn by Scotch and English. Across the valley to the northeast is a tall monument erected to the greatest of Scotch heroes, William Wallace. It stands on a rocky cliff and is visible for miles around, and it commands the scene of Wallace's most famous encounter with the English. He was posted on the north bank of the Firth of Forth, which here has the breadth of a moderate river and was spanned at that rime by a single narrow wooden bridge. The enemy, fifty thousand strong, lay on the opposite side, but after some days' delay began to file over. Until half the English had crossed the bridge, Wallace held his followers in check and gave no sign. Then he fell on the invaders with such determination that they were thrown into confusion and a headlong rout ensued. Thousands were slain, and many more were drowned in the river, and Wallace for the time being had "set his country free," as he had declared was his intention. Barely three miles from Stirling is a still more notable battleground — the field of Bannockburn. I found conveyance thither in a public omnibus which left me right in the centre of the ancient scene of conflict on a broad hilltop. From here Bruce is said to have directed the battle, and a heavy stone embedded in the earth is pointed out as having served him as a seat and a support for his flagstaff. The stone was flat and had a hole in the middle, and looked very like a common grindstone; but lest any one should be tempted to carry it off for such use it has been slatted over with iron rods — or was this to preserve it from the desecration of the relic hunters? I followed the rustic road down the hill and stopped on a quaint old "brig" arching the stream that gave the battlefield its name. In the ravine below me was the Bannockburn, a pretty brook worrying along through the boulders that filled its channel, and wandering away in a crooked course through the peaceful farm fields. I could detect no sign that a great battle had ever been fought here, so slight is the effect on nature of man's turmoils. The seasons as they come and go erase all marks of ravage and devastation, and quickly restore the tranquillity that has been momentarily interrupted. Bannockburn was the climax in the career of that most notable of all Scotch monarchs, Robert Bruce. In the year 1290 we find him one of thirteen pretenders to the throne, and he spent fifteen years thereafter courting the favor of the king of England. At the end of that period he withdrew to Scotland. Immediately afterward he attracted general attention by stabbing a rival claimant at Dumfries, in the church of the Grey Friars. Then he hastened to Scone and assumed the crown. Scotland was at once roused to arms, and war with England began. For a time the Scotch only met disaster, and Bruce had to fly to the Highlands. He found the chiefs there bitterly hostile to his cause, and during several years his experiences were those of a desperate adventurer. But adversity made him a noble leader of a nation's cause. He was hardy and strong, of commanding presence, brave, and genial in temper. The legends tell how he was tracked by bloodhounds into the remote glens, how he on one occasion held a pass single-handed against a crowd of savage clansmen, how sometimes he and his little band of fugitives had nought to eat save what they could get by hunting and fishing, and how Bruce himself had more than once to fling off his shirt of mail and scramble up the crags to escape his pursuers. Little by little, however, his affairs grew brighter, until at length the Black Douglas espoused his cause. From that time Bruce rapidly won adherents and territory, and by 1313 he had retaken nearly all the kingdom, and even invaded the northern counties of England, levying money and gathering such plunder as he could carry away. Only Stirling castle remained to the English, and the governor of that stronghold was so sorely pressed he agreed, unless meanwhile relieved, to surrender on June 24 of the following year. The English, to avoid this catastrophe and to prevent Scotland from slipping wholly out of their hands, collected an enormous army. It numbered not far from one hundred thousand fighting men, though a large proportion consisted of wild marauders from Ireland and Wales whose efficiency was not all it might be. Bruce by his utmost efforts could only muster thirty thousand, yet he prepared to confront the enemy a little to the south of Stirling. The position he selected was on the banks of the Bannockburn, where he was protected in part by the stream, and in part by numerous pits and trenches he directed his soldiers to dig. June 23d the English appeared and attempted unsuccessfully to force an entrance into the castle of Stirling with a body of cavalry. This failure was depressing, and they were still further disheartened by an incident of the evening. An English knight, Henry de Bohun, observing Bruce riding along in front of his army, had made a sudden dash on him, intending to thrust him through with his spear. The king was mounted on a small hackney and held in his hand only a light battle-axe, but he parried his opponent's spear and cleft his skull with so powerful a blow that the handle of the axe was shattered in his grasp. On the day following, the English advanced and assailed the whole line of the Scotch army, wrestling with it in a hand-to-hand combat. But the northern spearmen withstood the southern lancers and archers, and the desperate charges, many times repeated, only resulted in adding fresh heaps to the slain laid low by the valorous Scotch. The air was full of flying arrows and was hideous with the noise of clashing armor, the commingling of war-cries, and the groans of the wounded. Blood everywhere stained the ground, which was strewn with shreds of armor, broken spears, arrows, and pennons torn and soiled. The burn itself was so choked with fallen men and horses that it could be crossed dry-shod. As the day progressed, the attack weakened, and the Scotch began to push forward; and finally the unexpected appearance of a body of the northern camp-followers whom the English mistook for reinforcements to their opponents made the invading host give way along the whole front. Bruce perceived this, and led his troops with redoubled fury against the failing ranks of the enemy. This onset turned the English defeat into a disorderly rout. All encumbrances were thrown away, and they made their way as best they could back to England, and if the Scotch had had sufficient cavalry, scarcely any would have escaped. Even as it was, nearly one-third of the original army was left dead on the field, including two hundred knights and seven hundred squires. The loss of the Scotch was four thousand. By this victory at Bannockburn Bruce was firmly established on his throne and the independence of the kingdom was won, although desultory fighting continued for years.  Queen Mary's Prison on an Isle of Lochleven |