| Web

and Book

design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2009 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

VI

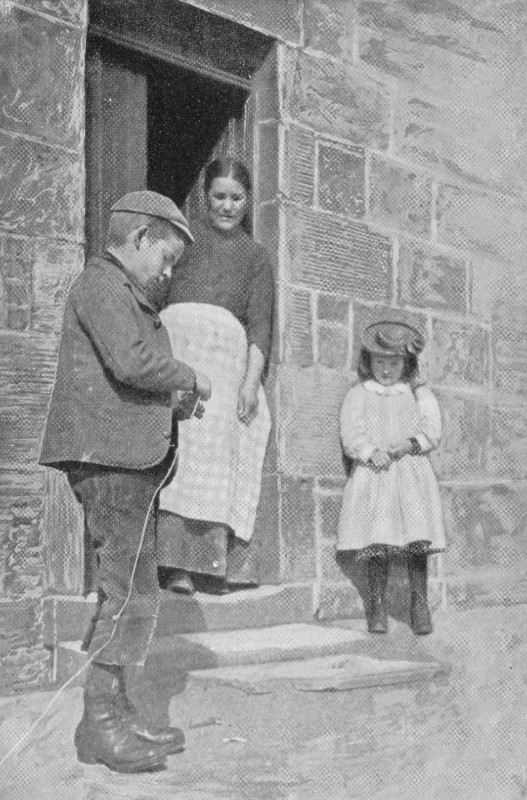

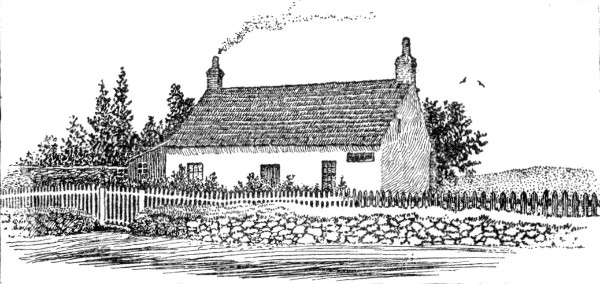

THRUMS  Palaulays IN nearly all the novels with which Mr. J. M. Barrie has charmed the readers of two hemispheres, Thrums is the home of the characters introduced, and is the scene of most of the comedies and tragedies the author delights to depict. As the background of the entertaining mingling of life's lights and shadows which is characteristic of his stories, it is a great satisfaction to find that Thrums is a real place and that it accords in many ways with Mr. Barrie's descriptions. Its name on the maps is Kirriemuir, though the inhabitants commonly shorten this to simply Kirrie; and you will find it about sixty miles north of Edinburgh, at the end of a little branch railroad that leaves the main line at Forfar and climbs half a dozen twisty miles toward the hills. The industry that makes and supports the town is weaving, and in the hollow, where a little stream winds through the village, are two great stone mills that look very substantial and prosperous. They do work which fifty years ago was done wholly in the homes. Then, one would have heard the rattle of the hand-loom from every cottage, but now the mills furnish employment for most of the town inhabitants, and, though there is loss of picturesqueness, the people are undoubtedly better off. A few still cling to the ways of their forefathers, and from an occasional house the old-time clack of weaving even yet comes to the ears of the passer. However, competition with machinery is a losing struggle, and the hand-workers grow fewer every year. As a rule the people appeared neater and thriftier than those of the average Scotch town. There were none of the barefoot women and few of the barefoot children that one finds plentiful in most villages. Making a living is not as oppressive a grind in Kirrie as it might be. If a street musician strays into the place, he is sure to carry away a liberal weight of small coins, and when a circus takes possession of the little square, it is always well patronized. This small paved square, bounded about by the various shops of the tradespeople, with the tiny town hall on one side, is the village centre. From it the houses streak away in the most chancing fashion up the valleys and along the hillsides. No doubt this haphazard character is due to the uncertain and hummocky lay of the land. Wherever you walk you are either going up or down a hill, and the hill is likely to be steep at that. The streets are crooked and have unexpected turns in them, and there are frequent little lanes that have an odd way of jerking around corners and dodging under houses. The dwellings are nearly all of red sandstone from a quarry high on the hillside. In most cases the houses are weather-darkened and battered, though some of the older cottages have walls coated with plaster, and certain others get periodical brightenings of whitewash. To the last class belongs the house that of all others in Thrums is the centre of the Barrie interest. You go down a steep hill from the town square, cross the stone brig that spans the burn, and at once begin the ascent of the famous brae (the Scotch word for a steep roadway or hillside). When you get to the elbow of the brae, there is Hendry's cot before you at the top of the hill. It is a one-story house with a narrow garden in front, and in its gable is a tiny window that you feel sure is Jess's window as soon as you see it. This window looks easterly down the brae and over the town; and it is remarkable when one goes about the village and the surrounding hill-slopes how often the cot at the top of the brae is in sight, and how the little window seems watching you as if the house had an eye. In Mr. Barrie's description the cottage roof is of thatch, with ropes flung over it to keep it on in wind. But now the roof is rudely slated. Thatch is out of date in Kirriemuir. Yet there was one rusty line of cottages on a neighboring hill that still retained its ancient coat of straw, and the straw was secured from the clutches of the gales by strips of board fastened on it.  In the Tenements Hendry's cot had tenants, and they were plainly of a thrifty turn of mind, for a black sign hung on the house walls that labelled the place "A Window in Thrums," and announced that souvenirs and lemonade were for sale. If you choose to go up the short walk through the garden and rap at the door, the dwellers within will readily show you the house interior. There is not much to see — just two small rooms with a bit of a passage between. To the right is the kitchen, with its fireplace, bed, table, and a few other primitive furnishings. To the left is "the room," in which is a second bed, several haircloth chairs, and a spreaded table with an elaborate lamp on it, and a few books laid around the edges in regular order. Upstairs is an unfinished attic that you climb to by a step-ladder through a trap-door, exactly as in the days when the schoolmaster boarded in the house. There is very little save dust and rubbish in the attic now, but it is lighted by the little window that gives the name to Mr. Barrie's book, though, for the sake of realism, this window should be in the kitchen below. The working class in Thrums had but a poor opinion of the novelist's books. Nothing happens in "A Window in Thrums," they informed me deprecatingly, but what they saw every day. The talk was the talk they heard next door — mere "bairn's havers," they said, "juist Kirrie balderdash." They thought it was unquestionably great rubbish, and accounted for its popularity by the theory that chance had made it a fad; after this factitious interest had faded they had no doubt other folks would be as sick of the stuff as they were. Nor were they suited with the author himself. He is not large enough, is too retiring, goes about with his hands behind him, looking straight ahead as if he lived in some dream world of his own — and how could you expect a man of that size and manner to write anything worth while? Among those who thus criticised Mr. Barrie was a woman who told me a long story of how she and her parents and children and grandchildren had all lived in the little Window in Thrums house. They had only recently moved out of it, and she supposed they were the real heroes and heroines of Barrie's tale. Like enough she, herself, was meant for Jess — if she wasn't, she didn't know who was. Then she said she would tell me the true origin of the title of the book. One stormy night some young fellows set out to rob a neighboring orchard and they wanted her son to go out with them. They knew he slept in the attic, and so they took some apples and came into the garden and threw them up at the little window to arouse him. Her son was away, as it happened, and pretty soon she and her sister, sleeping below, heard the apples come rolling down through the trap-door from the vacant apartment overhead. They were scared, and they awakened their father, who found the little window broken, and the rain pouring in. He called down to them how it was — and what should he do? In a corner of the loomshop at the far end of the house were a lot of "thrums" — waste ends of the warp which have to be cut off every time the weaving of a roll of cloth is finished. It was these thrums they used to stop the window and keep the rain out. That made "The Window in Thrums," or, more properly, "the thrums in the window." I fancy this origin of the title would be news to Mr. Barrie himself. The first nine years of his life the novelist lived in "the tenements," a block of old, plastered houses which are the homes of the humblest of the weavers. It was there he picked up his close knowledge of the language and ways of the poor, and his keen feeling for all their traits, from petty pride up to unconscious heroism. In later years his abode was in a substantial stone house just across the road from Hendry's cot at the top of the brae. Curiously enough, Mr. Barrie has never been inside the cottage he has made famous. But his readers and admirers go through it with sufficient care to make up for his delinquency, and they spare no effort to make the little house fit his descriptions in every detail. It is a little remarkable how many places can be identified in the Kirriemuir region as the veritable ones described in the book. First, of course, is the cot and the little window, and the brae with its carts and its people always going up and down. Then, near by, is the steep hillside of the commonty bounded about with hedgerows, and crisscrossed with uncared-for dirt paths. Here the children play, and here the women still come at times to dry their washing. T'nowhead farm and its pigpen are not far away, and at the other side of the town is the auld licht manse that was the home of "The Little Minister." The burying-ground road still climbs to the hillside cemetery with all its old-time straightness, and on the village borders is "The Den," of which so much is made in "Sentimental Tommy." This den, or, to use the English equivalent for the word — this ravine, is a bit of meadow hemmed about with steep, grassy ridges and rocky precipices. The villagers gather in the den every pleasant summer evening and lounge on the grass, or loiter along the walks, or play tames and join in a Highland dance to the music of the village band. One of the people whom I met in Kirriemuir was the dulseman. He was the same whom Hendry used to patronize, and I saw him every evening with his barrow on the square. He was a very stolid, slow sort of person, whom nothing short of an earthquake could have moved to the least excitement. On his barrow he carried a long box that held a bushel or two of the seaweed, and a shorter box that contained a couple of kettles full of buckies (sea-snails) which he had boiled with a flavoring of salt that day. The evening loiterers bought and ate these things much the same as our loiterers buy and eat peanuts. When a Kirrie man approached the dulse-barrow, he turned sidewise to it and said, "Penny's worth o' buckies," and the dulseman scooped up a tin cup full and emptied them into his customer's coat pocket. Then the man helped himself to a pin out of a rusty tray in the bucky box, or pulled one out of the bottom of his vest, and went over to the curbing, where he talked with his friends, and at the same time extracted the morsels from their shells. The shells were dropped on the paving of the square, and it was astonishing what a strewing of them there was by the end of the evening. If a man bought dulse, the vendor picked up his fingers full twice for a bawbee (halfpenny) and stuffed it in the man's pocket for him to nibble at leisure. When a woman bought, she received her seaweed in her apron, while the children usually carried theirs off in their hats. I was told that buckies were not good for one's stomach — they only pleased the palate, but that the dulse was medicinal, and helped digestion. I tried a bit of the seaweed one evening, and, except that it was leathery, and that its peculiar salt-water taste stayed in my mouth for an hour afterward, it was not bad. I did not get up sufficient courage to try the buckies. When twisted out of their shells, they looked too like dark earthworms to be appetizing. The most old-fashioned of all the Thrums dwellings were those that made the line of cottages under the thatched roof. In the far end of this line of cottages lived Jimmie Donaldson and his granddaughter. Jimmie was a telegraph boy, and, in spite of his ninety years, was always ready to run with messages night or day. He thought nothing of a six or eight mile tramp. He was a kindly, talkative slip of an old man, very poor, yet too independent to take a tip for small services. His work brought him only intermittent wages, and this fact often made him so downhearted that he found it necessary to cheer himself up by spending what he earned for occasional drops of liquor. The granddaughter worked in the mill, and it was she who was the mainstay of the household.  Spinning a "Peerie" Jimmie had three rooms, but as one was a rude scullery that looked like a cellar, and another a loft used only for storage, the little kitchen was practically the home and all of it. This kitchen had a tiny fireplace, two small tables, a tall clock, a few chairs that only the greatest care would coax to stand level on the uneven dirt floor, and some other odds and ends. Two box beds filled one side of the room. A great many of the Kirrie kitchens had box beds in them. This type of bed, as its name signifies, is literally in a box, but the box is of enormous size and extends from floor to ceiling, and the lid instead of being on the top is on the side fronting the room, and takes the form of double doors that fold back to give convenient entrance. The idea is that you can step in, pull the doors to, and prepare for bed without its making any difference whether the room is occupied or not. After you are under the clothes you push the door open and get some air to breathe. Old-fashioned people believe that the box bed has special advantages in time of sickness; for if the patient wishes quiet and darkness, it is only necessary to close the doors and the invalid is shut away from the outer world completely, with no trouble at all. In the kitchen that I have described the telegraph boy, Jimmie, and his granddaughter cooked, ate, washed, made their toilets — did everything. But Jimmie was satisfied. He said a doctor had told him that people who slept in a box bed and had a thatch roof overhead and a dirt floor underfoot lived the longest. He was much interested in the "States," and said he had two daughters over there, one in Meriden, Con., and the other in Mish. I don't know what he thought Con. and Mish. were, but I recognized Connecticut and Michigan. My final sight of Jimmie was on the last evening of my stay in Kirriemuir. I was in the stationer's shop on the square when the old man came in and held out a grimy hand for me to shake. His face was red, for he had been having a dram or two, and he was inclined to take a dismal view of life. He'd only had "telegram the week, only a saxpence, and a man could no live on that." The stationer offered him his snuff-box, and Jimmie took a pinch, but it did not revive his spirits, and his farewell to me was full of dubious foreboding. "I shall never see you again," he said. Oh, perhaps you may," I responded, with an attempt at cheerfulness. "You come next year?" he inquired. "But I won't be here if you do," he added. "I'll be in hell then." He shook hands once more, said "Good-by," and went out on the street.  The Window in Thrums House |