| Web

and Book

design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2015 (Return

to Web

Text-ures)

|

(HOME)

|

|

PART I

THE VOYAGE TO EASTER ISLAND

Charua Bay, Patagonian Channels THE START Why we went to Easter Island — The Building and Equipping of the Yacht — The Start from Southampton — Dartmouth — Falmouth. "All

the seashore is lined with numbers of stone idols, with their backs

turned

towards the sea, which caused us no little wonder, because we saw no

tool of

any kind for working these figures." So wrote, a century and a half

ago,

one of the earliest navigators to visit the Island of Easter in the

South-east

Pacific. Ever since that day passing ships have found it

incomprehensible that

a few hundred natives should have been able to make, move, and erect

numbers of

great stone monuments, some of which are over thirty feet in height;

they have

marvelled and passed on. As the world's traffic has increased Easter

Island has

still stood outside its routes, quiet and remote, with its story

undeciphered.

What were these statues of which the present inhabitants know nothing?

Were

they made by their ancestors in forgotten times or by an earlier race?

Whence

came the people who reached this remote spot? Did they arrive from

South

America, 2,000 miles to the eastward? Or did they sail against the

prevailing

wind from the distant islands to the west? It has even been conjectured

that

Easter Island is all that remains of a sunken continent. Fifty years

ago the

problem was increased by the discovery on this mysterious land of

wooden

tablets bearing an unknown script; they too have refused to yield their

secret. When,

therefore, we decided to see the Pacific before we died, and asked the

anthropological authorities at the British Museum what work there

remained to

be done, the answer was, "Easter Island." It was a much larger

undertaking than had been contemplated; we had doubts of our capacity

for so

important a venture; and at first the decision was against it, but we

hesitated

and were lost. Then followed the problem how to reach the goal. The

island

belongs to Chile, and the only regular communication, if regular it can

be

called, was a small sailing vessel sent out by the Chilean Company, who

use the

island as a ranch; she went sometimes once a year, sometimes not so

often, and

only remained there sufficient time to bring off the wool crop. We felt

that

the work on Easter ought to be accompanied with the possibility of

following up

clues elsewhere in the islands, and that to charter any such vessel as

could be

obtained on the Pacific coast, for the length of time we required her,

would be

unsatisfactory, both from the pecuniary standpoint and from that of

comfort. It

was therefore decided, as Scoresby is a keen yachtsman, that it was

worth while

to procure in England a little ship of our own, adapted to the purpose,

and to

sail out in her. As the Panama Canal was not open, and the route by

Suez would

be longer, the way would lie through the Magellan Straits. Search

for a suitable vessel in England was fruitless, and it became clear

that to get

what we wanted we must build. The question of general size and

arrangement had

first to be settled, and then matters of detail. It is unfortunate that

the precise

knowledge which was acquired of the exact number of inches necessary to

sleep

on, to sit on, and to walk along is not again likely to be useful. The

winter

of 1910-11 was spent over this work, but the professional assistance

obtained

proved to be incompetent, and we had to begin again; the final

architect of the

little yacht was Mr. Charles Nicholson, of Gosport, and the plans were

completed the following summer. They were for a vessel of schooner rig

and

auxiliary motor power The length over all was 90 feet, and the

water-line 72

feet; her beam was 20 feet. The gross tonnage was 91 and the yacht

tonnage was

126. The

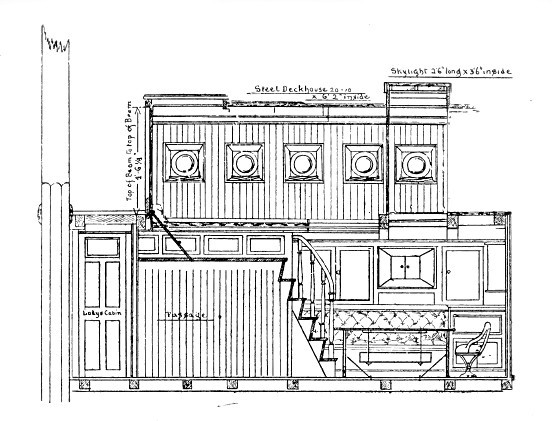

vessel was designed in four compartments, with a steel bulkhead between

each of

the divisions, so that in case of accident it would be possible to keep

her

afloat. Aft was the little chart-room, which was the pride of the ship.

When we

went on board magnificent yachts which could have carried our little

vessel as

a lifeboat, and found the navigation being done in the public rooms, we

smiled with

superiority. Out of the chart-room were the navigator's sleeping

quarters, and

in the overhang of the stern the sail-locker. The next compartment was

given to

the engines, and made into a galvanised iron box in case of fire. It

contained

a motor engine for such work as navigation in and out of harbour and

traversing

belts of calm. This was of 38 h.p. and run on paraffin, as petrol was

disallowed by the insurance; it gave her 5½ knots. In the same

compartment was

the engine for the electric light: in addition the yacht had steam

heating. The

spaces between the walls of the engine-box and those of the ship were

given to

lamps, and to boatswain's stores. Then came

the centre of the ship, containing the quarters of our scientific

party. The

middle portion of this was raised three or four feet for the whole

length,

securing first a deckhouse and then a heightened roof for the saloon

below, an

arrangement which was particularly advantageous, as no portholes were

allowed

below decks, leaving us dependent on skylights and ventilators.

Entering from

without, two or three steps led down into the deck-house, which formed

part of

the saloon, but at a higher level; it was my chief resort throughout

the

voyage. On each side was a settee, which was on the level of the deck,

and thus

commanded a view through port-holes and door of what was passing

outside; one

of these settees served as a berth in hot weather. A small companion

connected

the deck-house with the saloon below: the latter ran across the width

of the

ship; it also had full-length settees both sides, and at the end of

each was a

chiffonier. On the port side was the dinner-table, which swung so

beautifully

that the fiddles were seldom used, and the thermos for the navigating

officer

could be left happily on it all night. Starboard was a smaller table,

fitted

for writing; and a long bookshelf ran along the top of the for'ardside

(fig. 1A). On the

afterside of the saloon a double cabin opened out of it, and a passage

led to

two single cabins and the bathroom. The cabins were rather larger than

the

ordinary staterooms of a mail steamer, and the arrangements of course

more

ample; every available cranny was utilised for drawers and lockers, and

in

going ashore it was positive pain to see the waste of room under beds

and sofas

and behind washing-stands. My personal accommodation was a chest of

drawers and

hanging wardrobe, besides the drawers under the berth and various

lockers.

Returning to the saloon, a door for'ard opened into the pantry, which

communicated with the galley above, situated on deck for the sake of

coolness.

For'ard again was a whole section given to stores, and beyond, in the

bows, a

roomy forecastle. The yacht had three boats — a lifeboat which

contained a

small motor engine, a cutter, and a dinghy; when we were at sea the two

former

were placed on deck, but the dinghy, except on one occasion only, was

always

carried in the davits, where she triumphantly survived all

eventualities, a

visible witness to the buoyancy of the ship. While the

plans were being completed, search was being made for a place where the

vessel

should be built; for though nominally a yacht, the finish and build of

the

Solent would have been out of place. It had been decided that she

should be of

wood, as easier to repair in case of accident where coral reefs and

other

unseen dangers abound; but the building of wooden ships is nearly

extinct. The

west country was visited, and an expedition made to Dundee and

Aberdeen, but

even there, the old home of whalers, ships are now built of steel;

finally we

fixed on Whitstable, from which place such vessels still ply round the

coast.

The keel was laid in the autumn of 1911; the following spring we took

up our

abode there to watch over her, and there in May 1912 she first took the

water,

being christened by the writer in approved fashion. “I name this ship Mana, and may the blessing of God go

with her and all who sail in her" — a ceremony not to be performed

without

a lump in the throat. The choice of a name had been difficult; we had

wished to

give her one borne by some ship of Dr. Scoresby, the Arctic explorer, a

friend

of my husband's family whose name he received, but none of them proved

to be

suitable. The object was to find something which was both simple and

uncommon;

all appellations that were easy to grasp seemed to have been already

adopted,

while those that were unique lent themselves to error. “How would it do

in a

cable?” was the regulation test. Finally we hit on Mana,

which is a word well known to anthropologists, and has the

advantage of being familiar throughout the South Seas. We generally

translated

it somewhat freely as "good luck." It means, more strictly,

supernatural power: a Polynesian would, for instance, describe the

common idea

of the effect of a horseshoe by saying that the shoe had "Mana."

From a scientific standpoint Mana is probably the

simplest form of

religious conception. The yacht flew the burgee of the Royal Cruising

Club.

From the

time the prospective expedition became public we received a

considerable amount

of correspondence from strangers: some of it was from those who had

special

knowledge of the subject, and was highly valued; other letters had a

comic

element, being from various young men, who appeared to think that our

few

berths might be at the disposal of anyone who wanted to see the world.

One

letter, dated from a newspaper office, stated that its writer had no

scientific

attainments, but would be glad to get up any subject required in the

time

before sailing; the qualification of another for the post of steward

was that

he would be able to print the menus and ball programmes. The most

quaint

experience was in connection with a correspondent who gave a good name

and

address, and offered to put at our disposal some special knowledge on

the

subject of native lore, which he had collected as Governor of one of

the South

Sea islands. On learning our country address, he wrote that he was

about to

become the guest of some of our neighbours and would call upon us. It

subsequently transpired that they knew nothing of him, but that he had

written

to them, giving our name. He did, in fact, turn up at our cottage

during our

absence, and obtained an excellent tea at the expense of the caretaker.

The next

we heard of him was from the keeper of a small hotel in the

neighbourhood of

Whitstable, where he had run up a large bill on the strength of a

statement

that he was one of our expedition, and we found later that he had shown

a

friend over the yacht while she was building, giving out he was a

partner of my

husband. We understand that after we started he appeared in the county

court at

the instance of the unfortunate innkeeper. After

much trouble we ultimately selected two colleagues from the older

universities.

The arrangement with one of these, an anthropologist, was,

unfortunately, a

failure, and ended at the Cape Verde Islands. The other, a geologist,

Mr.

Frederick Lowry-Corry, took up intermediate work in India, and

subsequently

joined us in South America. The Admiralty was good enough to place at

our

disposal a lieutenant on full pay for navigation, survey, and tidal

observation. This post was ultimately filled by Lieutenant D. R.

Ritchie, R.N. With

regard to the important matter of the crew, it was felt that neither

merchant

seamen nor yacht hands would be suitable, and a number of men were

chosen from

the Lowestoft fishing fleet. Subsequent delays, however, proved

deleterious,

the prospective "dangers" grew in size, and the only one who

ultimately sailed with us was a boy, Charles C. Jeffery, who was

throughout a

loyal and valued member of the expedition. The places of the other men

were

supplied by a similar class from Brixham, who justified the selection.

The

mate, Preston, gave much valuable service, and one burly seaman in

particular.

Light by name, by his good-humour and intelligent criticism added

largely to

the amenity of the voyage. An engineer, who was also a photographer,

was

obtained from Glasgow. We were particularly fortunate in our sailing

master,

Mr. H. J. Gillam. He had seen, while in Japan, a notice of the

expedition in a

paper, and applied with keenness for the post; to his professional

knowledge,

loyalty, and pleasant companionship the successful achievement of the

voyage is

very largely due. The full complement of the yacht, in addition to the

scientific members, consisted of the navigator, engineer, cook-steward,

under-steward, and three men for each watch, making ten in all. S. was

official

master, and I received on the books the by no means honorary rank of

stewardess. Whitstable

proved to be an unsuitable place for painting, so Mana

made her first voyage round to Southampton Water, where she

lay for a while in the Hamble River, and later at a yacht-builder's in

Southampton. The steward on this trip took to his bed with seasickness;

but as

he was subsequently found surreptitiously eating the dinner which S.

had been

obliged to cook, we felt that he was not likely to prove a desirable

shipmate,

and he did not proceed further. We had hoped to sail in the autumn, but

we had

our full share of the troubles and delays which seem inevitably

associated with

yacht-building: the engine was months late in the installation, and

then had to

be rectified; the painting took twice as long as had been promised; and

when we

put out for trial trips there was trouble with the anchor which

necessitated a

return to harbour. The friends who had kindly assembled in July at the

Hans

Crescent Hotel to bid us good speed began to ask if we were ever really

going to

depart. We spent the winter practically living on board, attending to

these

affairs and to the complicated matter of stowage. The

general question of space had of course been very carefully considered

in the

original designs. The allowance for water was unusually large, the

tanks

containing sufficient for two, or with strict economy for three months;

the

object in this was not only safety in long or delayed passages, but to

avoid

taking in supplies in doubtful harbours. Portions of the hold had to be

reserved

of course for coal, and also for the welded steel tanks which contained

the

oil. When these essentials had been disposed of, still more intricate

questions

arose with regard to the allotment of room; it turned out to be greater

than we

had ventured to hope, but this in no way helped, as every department

hastened

to claim additional accommodation and to add something more to its

stock.

Nothing was more surprising all through the voyage than the yacht's

elasticity:

however much we took on board we got everything in, and however much we

took

out she was always quite full. The

outfit for the ship had of course been taken into consideration, but as

departure drew near it seemed, from the standpoint of below decks, to

surpass

all reason; there were sails for fine weather and sails for stormy

weather, and

spare sails, anchors, and sea-anchors, one-third of a mile of cable,

and ropes

of every size and description. As

commissariat officer, the Stewardess naturally felt that domestic

stores were

of the first importance. Many and intricate calculations had been made

as to

the amount a man ate in a month, and the cubic space to be allowed for

the

same. It had been also a study in itself to find out what must come

from

England and what could be obtained elsewhere; kind correspondents in

Buenos

Aires and Valparaiso had helped with advice, and we arranged for fresh

consignments from home to meet us in those ports, of such articles as

were not

to be procured there or were inordinately expensive. The general amount

of provisions

on board was calculated for six months, but smaller articles, such as

tea, were

taken in sufficient quantities for the two years which it was at the

time

assumed would be the duration of the trip. We brought back on our

return a

considerable amount of biscuits, for it was found possible to bake on

board

much oftener than we had dared to hope. As a yacht we were not obliged

to

conform to the merchant service scale of provisions, our ship's

articles

guaranteeing "sufficiency and no waste." The merchant scale was

constantly referred to, but it is, by universal agreement, excessive,

and leads

to much waste, as the men are liable to claim what they consider their

right,

whether they consume the ration or not; the result is that a harbour

may not

unfrequently be seen covered with floating pieces of bread, or even

whole

loaves. The quantity asked for by our men of any staple foods was

always given,

and there were the usual additions, but we subsisted on about

three-fourths of

the legal ration. We had only one case of illness requiring a doctor,

and then

it was diagnosed as "the result of over-eating." It was a source of

satisfaction that we never throughout the voyage ran short of any

essential

commodity. There

were other matters in the household department for which it was even

more

difficult to estimate than for the actual food — how many cups and

saucers, for

example, should we break per month, and how many reams of paper and

quarts of

ink ought we to take. Our books had of course to be largely scientific,

a

sovereign's worth of cheap novels was a boon, but we often yearned

unutterably

for a new book. Will those who have friends at the ends of the earth

remember

the godsend to them of a few shillings so invested, as a means of

bringing

fresh thoughts and a sense of civilised companionship? For a library

for the

crew we were greatly indebted to the kindness of Lord Radstock and the

Passmore

Edwards Ocean Library. We were subsequently met at every available port

by a

supply of newspapers, comprising the weekly editions of the Times

and Daily Graphic, the Spectator;

and the papers of two Societies for Women's Suffrage. In

addition to the requirements for the voyage the whole equipment for

landing had

to be foreseen and stowed, comprising such things as tents, saddlery,

beds,

buckets, basins, and cooking-pots. We later regretted the space given

to some

of the enamelled iron utensils, as they can be quite well procured in

Chile,

while cotton and other goods which we had counted on procuring there

for barter

were practically unobtainable. Some sacks of old clothes which we took

out for

gifts proved most valuable. Among late arrivals that clamoured for

peculiar

consideration were the scientific outfits, which attained to gigantic

proportions. S., who had studied at one time at University College

Hospital,

was our doctor, and the medical and surgical stores were imposing:

judging from

the quantity of bandages, we were each relied on to break a leg once a

month.

Everybody had photographic gear; the geologist appeared with a huge

pestle and

other goods; there was anthropological material for the preserving of

skulls;

the surveying instruments looked as if they would require a ship to

themselves;

while cases of alarming size arrived from the Admiralty and Royal

Geographical

Society, containing sounding machines and other mysterious articles.

The owners

of all these treasures argued earnestly that they were of the essence

of the

expedition, and must be treated with respect accordingly. Then of

course things

turned up for which everyone had forgotten to allow room, such as spare

electric lamps, also a trammel and seine, each of fifty fathoms, to

secure fish

in port. Before we finally sailed a large consignment appeared of

bonded

tobacco for the crew, and the principal hold was sealed by the Customs,

necessitating a temporary sacrifice of the bathroom for last articles. This

packing of course all took time, especially as nothing could be allowed

to get

wet, and a rainy or stormy day hung up all operations. Finally,

however, on the

afternoon of February 28th, 1913, the anchor was weighed, and we went

down

Southampton Water under power. We were at last off for Easter Island! We had a

good passage down the Channel, stopped awhile at Dartmouth, for the

Brixham men

to say good-bye to their families, and arrived at Falmouth on March

6th. Here

there was experienced a tiresome delay of nearly three weeks. The wind,

which

in March might surely have seen its way to be easterly, and had long

been from

that direction, turned round and blew a strong gale from the

south-west. The

harbour was white with little waves, and crowded with shipping of every

description, from battleships to fishing craft. Occasionally a vessel

would

venture out to try to get round the Lizard, only to return beaten by

the

weather. We had while waiting the sad privilege of rendering a last

tribute to

our friend Dr. Thomas Hodgkin, the author of Italy and her

Invaders, who just before our arrival had passed

where "tempests cease and surges swell no more." He rests among his

own people in the quiet little Quaker burial-ground. It was

not till Lady Day, Tuesday, March 25th, that the wind changed

sufficiently to

allow of departure; then there was a last rush on shore to obtain

sailing

supplies of fresh meat, fruit, and vegetables, and to send off good-bye

telegrams. Everything was triumphantly squeezed in somewhere and

carefully

secured, so that nothing should shift when the roll began. The only

articles

which found no home were two sacks of potatoes, which had to remain on

the

cabin floor, because the space assigned to them below hatches had, in

my

absence on shore, been nefariously appropriated by the Sailing-master

for an

additional supply of coal. It was

dark before all was ready, and we left Falmouth Harbour with the motor;

then

out into the ocean, the sails hoisted, the Lizard Light sighted, and

good-bye

to England! "Two

years," said our friends, "that is a long time to be away."

"Oh no," we had replied; "we shall find when we come back that

everything is just the same; it always is. You will still be talking of

Militants, and Labour Troubles, and Home Rule; there will be a few new

books to

read, the children will be a little taller — that will be all." But the

result was otherwise. |