PREHISTORIC

REIMAINS

STATUES

AND CROWNS

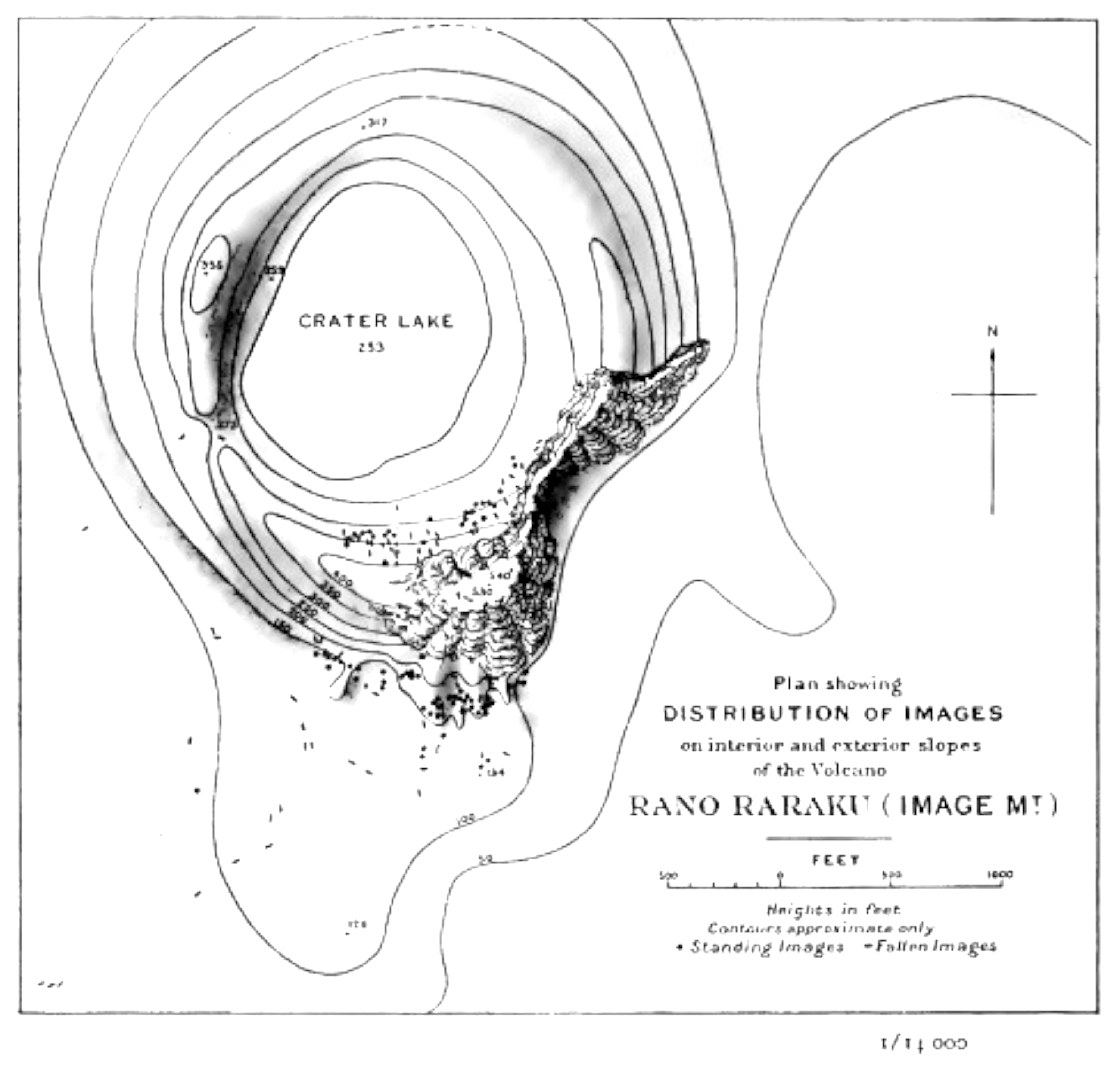

FIG 44.

FIG 44.

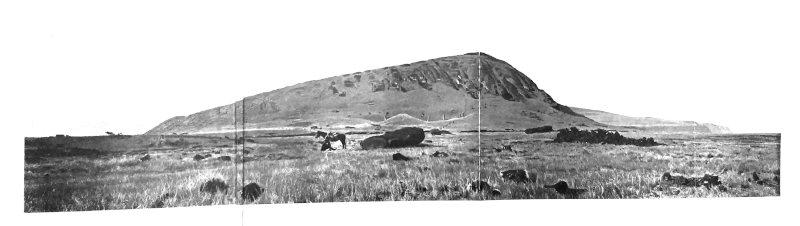

FIG 45. — RANO

RARAKU FROM THE SEA

FIG 45. — RANO

RARAKU FROM THE SEA

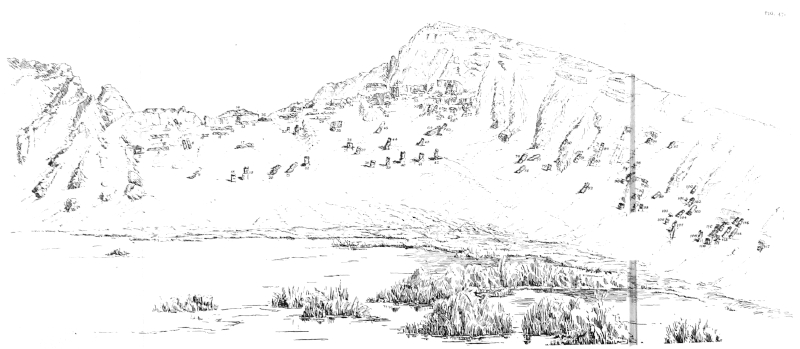

FIG 46. — RANO RARAKU

FROM THE SOUTH-WEST

Images prostrate in foreground and erect on slope; quarries above.

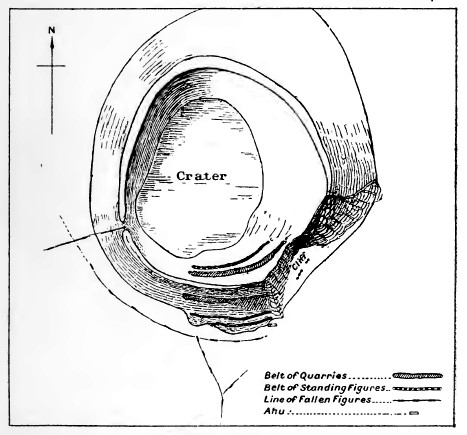

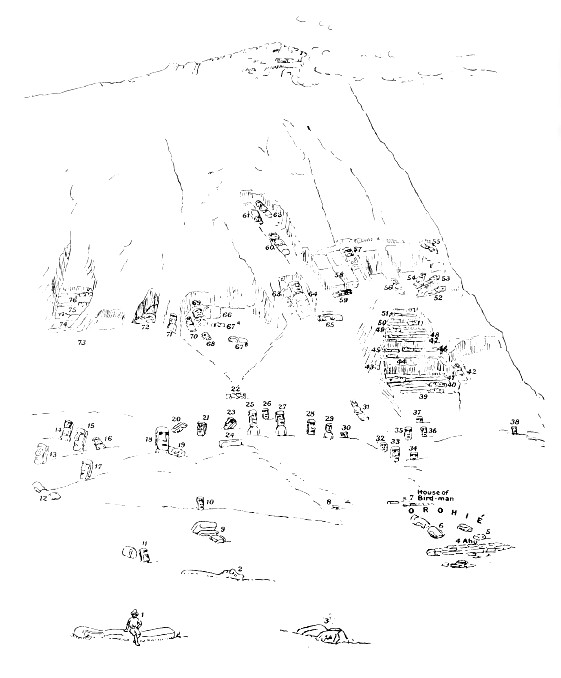

FIG. 47. — RANO RARAKU INTERIOR OF

CRATER

Diagrammatic sketch showing position of statues on slope and in quarry.

CHAPTER

XIV

PREHISTORIC

REIMAINS [continued)

STATUES

AND CROWNS

Rano

Raraku, its Quarries and Standing Statues — the South-east Face of the

Mountain

— Isolated Statues — Roads — Stone Crowns of the Images.

Strange

as it may appear, it is by no means easy to obtain a complete view of a

statue

on the island: most of the images which were formerly on the ahu lie on

their

faces, many are broken, and detail has largely been destroyed by

weather.

Happily, we are not dependent for our knowledge of the images on such

information as we can gather from the ruins on the ahu, but are able to

trace

them to their origin, though even here excavation is necessary to see

the

entire figure. Rano Raraku is, as has already been explained, a

volcanic cone

containing a crater-lake. It resembles, to use an unromantic simile,

one of the

china drinking-vessels dedicated to the use of dogs, whose base is

larger than

their brim. Its sides are for the most part smooth and sloping, and

several

carriages could drive abreast on the northern rim of the crater, but

towards

the south-east it rises in height, and from this aspect it looks as if

the

circular mass had been sliced do^\^l with a giant knife forming it into

a

precipitous cliff. The cliff is lowest where the imaginary knife has

come

nearest to the central lake, thus causing the two ends to stand out as

the

peaks already mentioned (fig. 45).

The

mountain is composed of compressed volcanic ash, which has been found

in

certain places to be particularly suitable for quarrying; it has been

worked on

the southern exterior slope, and also inside the crater both on the

south and south-eastern

sides. With perhaps a dozen exceptions, the whole of the images in the

island

have been made from it, and they have been dragged from this point up

hill and

down dale to adorn the terraces round the coast-line of the island;

even the

images on the ahu, which have fallen into the sea on the further

extremity of

the western volcano, are said to have been of the same stone. It is

conspicuous

in being a reddish brown colour, of which the smallest chips can be

easily

recognised. It is composite in character, and embedded in the ash are

numerous

lapilli of metamorphic rock. Owing to the nature of this rock the

earliest

European visitors came to the conclusion that the material was

factitious and

that the statues were built of clay and stones; it was curious to find

that the

marooned prisoners of war of our own time fell into the same mistake of

thinking

that the figures were "made up."

FIG. 48. — Diagram

of Rang Raraku.

FIG. 48. — Diagram

of Rang Raraku.

The

workable belt, generally speaking, forms a horizontal section about

half-way up

the side of the mountain. Below it, both on the exterior and within the

crater,

are banks of detritus, and on these statues have been set up; most of

them are

still in place, but they have been buried in greater or less degree by

the

descent of earth from above (fig. 57). Mr. Ritchie made a survey of the

mountain with the adjacent coast, but it was found impossible to record

the

results of our work without some sort of plan or diagram which was

large enough

to show every individual image. This was accomplished by first studying

each

quarry, note-book in hand, and then, with the aid of field-glasses,

amalgamating the results from below; the standing statues being

inserted in

their relation to the quarries above. It was a lengthy but enjoyable

undertaking.

Part of the diagram of the exterior has been redrawn with the help of

photographs (fig. 60); the plan of the inside of the crater is shown in

what is

practically its original form (fig. 47).

Quarries of Rano Raraku. —

Leaving on one side for the moment the figures on the lower slope, let

us in

imagination scramble up the grassy side, a steep climb of some one or

two

hundred feet to where the rock has been hewn away into a series of

chambers and

ledges. Here images lie by the score in all stages of evolution, just

as they

were left when, for some unknown reason, the workmen laid down their

tools for

the last time and the busy scene was still. Here, as elsewhere, the

wonder of

the place can only be appreciated as the eye becomes trained to see. In

the majority

of cases the statues still form part of the rock, and are frequently

covered

with lichen or overgrown with grass and ferns; and even in the

illustrations,

for which prominent figures have naturally been chosen, the reader may

find

that he has to look more than once in order to recognise the form. A

conspicuous one first strikes the beholder: as he gazes, he finds with

surprise

that the walls on either hand are themselves being wrought into

figures, and that,

resting in a niche above him, is another giant; he looks down, and

realises

with a start that his foot is resting on a mighty face. To the end of

our visit

we occasionally found a figure which had escaped observation. The

workings on

the exterior of Raraku first attract attention; here their size, and

incidentally that of many of the statues, has largely been determined

by

fissures in the hillside, which run vertically and at distances of

perhaps 40

feet. The quarries have been worked differently, and each has a

character of

its own. In some of them the principal figures lie in steps, with their

length

parallel to the hill's horizontal axis; one of this type is reached

through a

narrow opening in the rock, and recalls the side-chapel of some old

cathedral,

save that nature's blue sky forms the only roof (no. 74, fig, 60);

immediately

opposite the doorway there lies, on a base of rock, in quiet majesty, a

great

recumbent figure. So like is it to some ancient effigy that the awed

spectator

involuntarily catches his breath, as if suddenly brought face to face

with a

tomb of the mighty dead. Once, on a visit to this spot, a rather quaint

little

touch of nature supervened: going there early in the morning, with the

sunlight

still sparkling on the floor of dewy grass, a wild-cat, startled by our

approach, rushed away from the rock above, and the natives, clambering

up,

found nestling beneath a statue at a high level a little family of

blind

kittens.

FIG. 49. — STATUE

IN QUARRY, PARTIALLY

SCULPTURED.

[No. 41, Fig. 60]

FIG. 49. — STATUE

IN QUARRY, PARTIALLY

SCULPTURED.

[No. 41, Fig. 60]

In other

instances the images have been carved lying, not horizontally, but

vertically,

with sometimes the head, and sometimes the base, toward the summit of

the hill.

But no exact system has been followed, the figures are found in all

places, and

all positions. When there was a suitable piece of rock it has been

carved into

a statue, without any special regard to surroundings or direction.

Interspersed

with embryo and completed images are empty niches from which others

have

already been removed; and finished statues must, in some cases, have

been

passed out over the top of those still in course of construction. From

all the

outside quarries is seen the same wonderful panorama: immediately

beneath are

the statues which stand on the lower slopes; farther still lie the

prostrate

ones beside the approach; while beyond is the whole stretch of the

southern

plain, with its white line of breaking surf ending in the western

mountain of

Rano Kao (fig. 54).

FIG. 50. — STATUE

IN QUARRY.

Attached to rock by

"keel" only.

Top of head (flat surface) towards spectator. [No. 61. Fig. 60.]

FIG. 50. — STATUE

IN QUARRY.

Attached to rock by

"keel" only.

Top of head (flat surface) towards spectator. [No. 61. Fig. 60.]

The

quarries within the crater are on the same lines as those without, save

that

those on the south-eastern side form a more continuous whole. Here the

most

striking position is on the top of the seaward cliff, in the centre of

which is

a large finished image (no. 16, fig. 47); on one side the ground falls

away

more or less steeply to the crater-lake, on the other a stone thrown

down would

reach the foot of the precipice; the view extends from sea to sea. Over

all the

most absolute stillness reigns.

The

statues in the quarries number altogether over 150. Amongst this mass

of

material there is no difficulty in tracing the course of the work. The

surface

of the rock, which will form the figure, has generally been laid bare

before

work upon it began, but occasionally the image was wrought lying

partially

under a canopy (fig. 49). In a few cases the stone has been roughed out

into

preliminary blocks (no. 58, fig. 60), but this procedure is not

universal, and

seems to have been followed only where there was some doubt as to the

quality

of the material. When this was not the case the face and anterior

aspect of the

statue were first carved, and the block gradually became isolated as

the

material was removed in forming the head, base, and sides. A gutter or

alley-way was thus made round the image (fig. 55) , in which the niches

where

each man has stood or squatted to his work can be clearly seen; it is,

therefore, possible to count how many were at work at each side of a

figure.

FIG. 51. — STATUE

IN QUARRY.

FIG. 51. — STATUE

IN QUARRY.

Ready to be

launched; movement prevented by stone wedges. Base towards spectator.

[No. 57.

Fig. 60.]

When the

front and sides were completed down to every detail of the hands, the

undercutting commenced. The rock beneath was chipped away by degrees

till the

statue rested only on a narrow strip of stone running along the spine;

those

which have been left at this stage resemble precisely a boat on its

keel, the

back being curved in the same way as a ship's bottom (fig. 50). In the

next

stage shown the figure is completely detached from the rock, and

chocked up by

stones, looking as if an inadvertent touch would send it sliding down

the hill

into the plain below (fig. 51). In one instance the moving has

evidently begun,

the image having been shifted out of the straight. In another very

interesting

case the work has been abandoned when the statue was in the middle of

its

descent; it has been carved in a horizontal position in the highest

part of the

quarry, where its empty niche is visible, it has then been slewed round

and was

being launched, base forward, across some other empty niches at a lower

level.

The bottom now rests on the floor of the quarry, and the figure, which

has

broken in half, is supported in a standing fashion against the outer

edge of

the vacated shelves. The first impression was that it had met with an

accident

in transit, and been abandoned; but it is at least equally possible

that for

the purpose of bringing it down, a bank or causeway of earth had been

built up

to level the inequalities of the descent, and that it was resting on

this when

the work came to an end; the soil would then in time be washed away,

and the

figure fracture through loss of support.

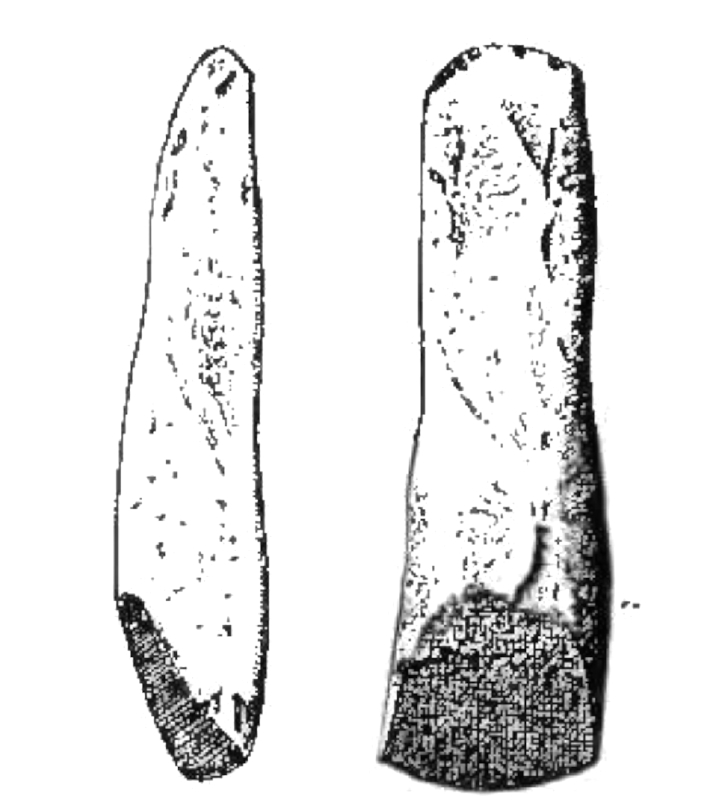

FIG. 52. —

STONE TOOLS (Toki).

FIG. 53. — H.

Balfour del.

FIG. 53. — H.

Balfour del.

In the

quarry which is shown in fig. 54, the finished head can be seen lying

across

the opening, the body is missing, presumably broken off and buried; the

bottom

of the keel on which the figure at one time rested can be clearly

traced in a

projecting line of rock down the middle of its old bed, also the

different

sections where the various men employed have chipped away the stone in

undermining the statue. In the quarry wall the niches occupied by the

sculptors

are also visible, at more than one level, the higher ones being

discarded when

the upper portion of the work was finished and a lower station needed.

The hand

of the standing boy in fig. 51 rests on a small platform similarly

abandoned.

FIG. 54. — HEAD OF

A STATUE AT MOUTH OF

QUARRY FROM WHICH IT HAS BEEN HEWN.

[No. 72. Fig. 60.]

FIG. 54. — HEAD OF

A STATUE AT MOUTH OF

QUARRY FROM WHICH IT HAS BEEN HEWN.

[No. 72. Fig. 60.]

The tools

were found with which the work has been done. One type of these can be

seen

lying about in great abundance (fig. 52). They are of the same material

as the

lapilli in the statues, and made by flaking. Some specimens are pointed

at both

ends, others have one end more or less rounded. It is unlikely that

they were

hafted, and they were probably held in the hand when in use. They were

apparently discarded as soon as the point became damaged. There is

another tool

much more carefully made, an adze blade, with the lower end bevelled

off to

form the cutting edge. In the specimen shown, the top is much abraded

apparently from hammering with a maul or mallet (fig. 53). These are

rarely

found, the probability being that they were too precious to leave and

were

taken home by the workmen. The whole process was not necessarily very

lengthy;

a calculation of the number of men who could work at the stone at the

same

time, and the amount each could accomplish, gave the rather surprising

result

that a statue might be roughed out within the space of fifteen days.

The most

notable part of the work was the skill which kept the figure so perfect

in

design and balance that it was subsequently able to maintain its

equilibrium in

a standing position; to this it is difficult to pay too high a tribute.

FIG. 55. — UPPER

PORTION OF LARGEST IMAGE IN

QUARRY, WITH ALLEY-WAY FOR WORKMEN.

[No. 64. Fig. 50.]

FIG. 55. — UPPER

PORTION OF LARGEST IMAGE IN

QUARRY, WITH ALLEY-WAY FOR WORKMEN.

[No. 64. Fig. 50.]

It

remains to account for the vast number of images to be found in the

quarry. A

certain number have, no doubt, been abandoned prior to the general

cessation of

the work; in some cases a flaw has been found in the rock and the

original plan

has had to be given up — in this case, part of the stone is sometimes

used for

either a smaller image or one cut at a different angle. In other

instances the

sculptors have been unlucky enough to come across at important points

one or

more of the hard nodules with which their tools could not deal, and as

the work

could not go down to posterity with a large wart on its nose or

excrescence on

its chin, it has had to be stopped. But when all these instances have

been

subtracted, the amount of figures remaining in the quarries is still

startlingly large when compared with the number which have been taken

out of

it, and must have necessitated, if they were all in hand at once, a

number of

workers out of all proportion to any population which the island has

ever been

likely to have maintained. The theory naturally suggests itself that

some were

merely rock-carvings and not intended to be removed. It is one which

needs to

be adopted with caution, for more than once, where every appearance has

pointed

to its being correct, a similar neighbour has been found which was

actually

being removed; on the whole, however, there can be little doubt that it

is at

any rate a partial solution of the problem. Some of the images are

little more

than embossed carvings on the face of the rock without surrounding

alley-ways.

In one instance, inside the crater, a piece of rock which has been left

standing on the very summit of the cliff has been utilised in such a

way that

the figure lies on its side, while its back is formed by the outward

precipice

(fig. 56); this is contrary to all usual methods, and it seems

improbable that

it was intended to make it into a standing statue. Perhaps the

strongest

evidence is afforded by the size of some of the statues: the largest

(fig. 55;

no. 64, fig. 60) is 66 feet in length, whereas 36 feet is the extreme

ever

found outside the quarry; tradition, it is true, points out the ahu on

the

south coast for which this monster was designed, but it is difficult to

believe

it was ever intended to move such a mass. If this theory is correct, it

would

be interesting to know whether the stage of carving came first, and

that of

removal followed, as the workmen became more expert; or whether it was

the

result of decadence when labour may have become scarce. It is, of

course,

possible that the two methods proceeded concurrently, rock-carvings

being

within the means of those who could not procure the labour necessary to

move

the statue.

Legendary

lore throws no light on these matters, nor on the reasons which led to

the

desertion of this labyrinth of work; it has invented a story which

entirely

satisfies the native mind and is repeated on every occasion. There was

a

certain old woman who lived at the southern corner of the mountain and

tilled

the position of cook to the image-makers. She was the most important

person of

the establishment, and moved the images by supernatural power (Mana), ordering them about at her will.

One day, when she was away, the workers obtained a fine lobster, which

had been

caught on the west coast, and ate it up, leaving none for her;

unfortunately

they forgot to conceal the remains, and when the cook returned and

found how

she had been treated, she arose in her wrath, told all the images to

fall down,

and thus brought the work to a standstill.

FIG. 56. — STATUE

CARVED ON EDGE OF

PRECIPICE. INTERIOR OF CRATER.

[No. 27. Fig. 47.]

FIG. 56. — STATUE

CARVED ON EDGE OF

PRECIPICE. INTERIOR OF CRATER.

[No. 27. Fig. 47.]

Standing Statues of Rano

Raraku. —

Descending from the quarries, we turn to the figures below. A few at

the foot

of the mountain have obviously been thrown down; one of these (no . 6,

fig. 60)

was wrecked in the same conflict as the one on Ahu Paro, and one is

shown where

an attempt has been made to cut off the head. Another series of images

have

originally stood round the base on level ground (nos. 1, 2, 3, fig.

60),

extending from the exterior of the entrance to the crater to the

southern

corner; these are all prostrate. On the slopes there are a few

horizontal

statues, but the great majority, both inside the crater and without,

are still

erect. Outside, some forty figures stand in an irregular belt, reaching

from

the corner nearest the sea to about half-way to the gap leading into

the

crater. The bottom of the mountain is here diversified by little

hillocks and

depressions; these hillocks would have made commanding situations, but

rather

curiously the statues, while erected quite close to them, and even on

their sides,

are never on the top. Inside the crater, where some twenty statues are

still

erect, the arrangement is rather more regular; but, on the whole, they

are put

up in no apparent order. All stood with their backs to the mountain.

No. 32.

No. 33.

No.

34.

FIG. 57. — STANDING

STATUES ON EXTERIOR OF

RANO RARAKU SHOWING PARTIAL BURIAL

No. 32.

No. 33.

No.

34.

FIG. 57. — STANDING

STATUES ON EXTERIOR OF

RANO RARAKU SHOWING PARTIAL BURIAL

They vary

very considerably in size; the tallest which could be measured from its

base

was 32 feet 3 inches, while others are not much above 11 feet. Every

statue is

buried in greater or less degree, but while some are exposed as far as

the

elbow, in others only a portion of the top of the head can be seen

above the

surface (fig. 57), others no doubt are covered entirely. The number

visible

must vary from time to time, as by the movement of the earth some are

buried

and others disclosed. An old man, whose testimony was generally

reliable,

stated, when speaking of the figures on the outside of the mountain,

that while

those nearer the sea were in the same condition as he always remembered

them,

those farther from it were now more deeply buried than in his youth.

Various

old people were brought out from the village at Hanga Roa to pay visits

to the

camp, but the information forthcoming was never of great extent; one

elderly

gentleman in particular took much more interest in roaming round the

mountain,

recalling various scenes of his youth, than in anything connected with

the

statues. A few names are still remembered in connection with the

individual

figures, and are said to be those of the makers of the images, and some

proof

is afforded of the reality of the tradition by the fact that the clans

of the

persons named are consistently given. Another class of names is,

however,

obviously derived merely from local circumstances; one in the quarry,

under a

drip from above, is known by the equivalent for "Dropping Water,"

while a series inside the crater are called after the birds which

frequent the

cliff-side, “Kia-kia, Flying," "Kia-kia, Sitting," and so forth.

A solitary legend relates to an unique figure, resembling rather a

block than

an image, which lies on the surface on the outside of the mountain (no.

24,

fig. 60). It is the single exception to the rule mentioned above, that

no

evolution can be traced in the statues on the island. The usual

conception is

there, and the hands are shown, but the head seems to melt into the

body and

the ear and arm to have become confused. It is said to have been the

first

image made and is known as Tai-hare-atua, which tradition says was the

name of

the maker. He found himself unable to fashion it properly, and went

over to the

other side of the island to consult with a man who lived near Hanga

Roa, named

Rauwai-ika. He stayed the night there, but the expert remained silent,

and he

was retiring disappointed in the morning, when he was followed by his

host, who

called him back. “Make your image," said he, “like me," — that is, in

form of a man.

On our

first visit to the mountain, overcome by the wonder of the scene, we

turned to

our Fernandez boy and asked him what he thought of the statues. Like

the

classical curate, when the bishop inquired as to the character of his

egg, he

struggled manfully between the desire to please and a sense of truth;

like the

curate, he took refuge in compromise. “Some of them," he said

doubtfully,

he thought "were very nice." If the figures at first strike even the

cultured observer as crude and archaic, it must be remembered that not

only are

they the work of stone tools, but to be rightly seen should not be

scrutinised

near at hand. “Hoa-haka-nanaia," for instance, is wholly and dismally

out

of place under a smoky portico, but on the slopes of a mountain, gazing

in

impenetrable calm over sea and land, the simplicity of outline is soon

found to

be marvellously impressive. The longer the acquaintance the more this

feeling

strengthens; there is always the sense of quiet dignity, of suggestion

and of

mystery.

FIG. 58 — STATUES

ON RANO RARAKU, SHOWING

DISTENSION OF EAR.

LOBE REPRESENTED AS

A ROPE.

[Nos. 27 and 29.

Fig. 60.]

FIG. 58 — STATUES

ON RANO RARAKU, SHOWING

DISTENSION OF EAR.

LOBE REPRESENTED AS

A ROPE.

[Nos. 27 and 29.

Fig. 60.]

FIG. 59. —LOBE

CONTAINING A DISC [No. 23.

Fig. 60.]

FIG. 59. —LOBE

CONTAINING A DISC [No. 23.

Fig. 60.]

FIG. 60A. — KEY TO

DIAGRAMMATIC SKETCH

FIG. 60A. — KEY TO

DIAGRAMMATIC SKETCH

FIG. 60. — EXTERIOR

OF RANO RARAKU. EASTERN

PORTION OF SOUTHERN ASPECT.

Diagrammatic sketch

showing position of

statues.

FIG. 60. — EXTERIOR

OF RANO RARAKU. EASTERN

PORTION OF SOUTHERN ASPECT.

Diagrammatic sketch

showing position of

statues.

FIG. 61. — DIGGING

OUT A STATUE.

For same image

after excavation see fig. 69.

FIG. 61. — DIGGING

OUT A STATUE.

For same image

after excavation see fig. 69.

While the

scene on Raraku always arouses a species of awe, it is particularly

inspiring

at sunset, when, as the light fades, the images gradually become

outlined as

stupendous black figures against the gorgeous colouring of the west.

The most striking

sight witnessed on the island was a fire on the hill-side; in order to

see our

work more clearly we set alight the long dry grass, always a virtuous

act on

Easter Island that the live-stock may have the benefit of fresh shoots;

in a

moment the whole was a blaze, the mountain, wreathed in masses of

driving

smoke, grew to portentous size, the quarries loomed down from above as

dark

giant masses, and in the whirl of flame below the great statues stood

out

calmly, with a quiet smile, like stoical souls in Hades.

The

questions which arise are obvious: do these buried statues differ in

any way

from those in the workings above, from those on the ahu or from one

another?

were they put up on any foundation? and, above all, what is the history

of the

mountain and the raison d’être of the

figures? In the hope of throwing some light on these problems we

started to dig

them out. It had originally been thought that the excavation of one or

two

would give all the information which it was possible to obtain, but

each case

was found to have unique and instructive features, and we finally

unearthed in

this way, wholly or in part, some twenty or thirty statues. It was

usually easy

to trace the stages by which the figures had been gradually covered. On

the top

was a layer of surface soil, from 3 to 8 inches in depth; then came

debris,

which had descended from the quarry above in the form of rubble, it

contained large

numbers of chisels, some forty of which have been found in digging out

one

statue; below this was the substance in which a hole had been dug to

erect the

image, it sometimes consisted of clay and occasionally in part of rock.

Not

unfrequently the successive descents of earth could be traced by the

thin lines

of charcoal which marked the old surfaces, obviously the result of

grass or

brushwood fires. The few statues which are in a horizontal position are

always

on the surface (no. 31, fig. 60), and at first give the impression that

they

have been abandoned in the course of being brought down from the

quarries; as

they are frequently found close to standing images, of which only the

head is

visible, it follows that, if this is the correct solution, the work

must still

have been proceeding when the earlier statues were already largely

submerged.

The juxtaposition, however, occurs so often that it seems, on the

whole, more

probable that the rush of earth which covered some, upset the

foundations of

others, and either threw them down where they stood or carried them

with it on

top of the flood. These various landslips allow of no approximate

deductions as

to the date, in the manner which is possible with successively

deposited layers

of earth.

To get

absolutely below the base of an image was not altogether easy. The

first we

attempted to dig out was one of the farther ones within the crater (no.

19,

fig. 47); it was found that, while the back of the hole into which it

had been

dropped was excavated in the soft volcanic ash, the front and remaining

sides

were of hard rock. This rock was cut to the curvature of the figure at

a

distance of some 3 inches from it, and as the chisel marks were

horizontal,

from right to left, the workmen must have stood in the cup while

preparing it:

in clearing out the alluvium between the wall of the cup and the

figure, six

stone implements were found. The hands, which were about 1 foot below

the level

of the rim, were perfectly formed. The next statue chosen for

excavation was

also inside the crater (no. 107, fig. 47); it was most easily attacked

from the

side, and this time it was possible to get low enough to see that it

stood on

no foundation, and that the base instead of expanding, as with those

which

stood on the ahu, contracted in such a manner as to give a peg-shaped

appearance; this confirmed the impression made by the previous

excavation, that

the image was intended to remain in its hole and was not, as some have

stated,

merely awaiting removal to an ahu (fig. 62).

EXCAVATED

IMAGES.

FIG. 62. — Showing

effect of weathering and

peg-shaped base.

[No. 107. Fig. 47.]

FIG. 62. — Showing

effect of weathering and

peg-shaped base.

[No. 107. Fig. 47.]

FIG. 63. — Showing

scamped work in lower part

of figure, no right hand carved, and surface only coarsely chiselled.

[No. 36. Fig. 47.]

DESIGNS

ON BACKS OF IMAGES.

FIG. 63. — Showing

scamped work in lower part

of figure, no right hand carved, and surface only coarsely chiselled.

[No. 36. Fig. 47.]

DESIGNS

ON BACKS OF IMAGES.

FIG. 64. —

BACK OF AN EXCAVATED STATUE.

Showing

{a) typical raised rings and girdle; (6) exceptional incised carvings.

[No. 109.

Fig. 47.]

FIG. 64. —

BACK OF AN EXCAVATED STATUE.

Showing

{a) typical raised rings and girdle; (6) exceptional incised carvings.

[No. 109.

Fig. 47.]

P.

Edmunds.

FIG. 65. — STATUE

ON AN AHU AT ANAKENA. Rings

on centre and lower portion of back.

P.

Edmunds.

FIG. 65. — STATUE

ON AN AHU AT ANAKENA. Rings

on centre and lower portion of back.

The story

was shown not only in the sections of the excavation, but in the

degrees of

weathering on the figure itself: the lowest part of the image to above

the

elbow exhibited, by the sharpness of its outlines and frequently of the

chisel

cuts also, that it had never been exposed, the other portions being

worn in

relative degrees. Traces of the smoothness of the original surface can

still be

seen above-ground in the more protected portions of some of the

statues, such

as in the orbit and under the chin (see frontispiece); but a much

clearer

impression is of course gained of the finish and detail of the image

when the

unweathered surface is exposed. The polish is often very beautiful, and

pieces

of pumice, called "punga," are found, with which the figures are said

to have been rubbed down. The fingers taper, and the excessive length

of the

thumb-joint and nail are remarkable (fig. 72). The nipples are in some

cases so

pronounced that the natives often characterised them as feminine, but

in no

case which we came across did the statues represent other than the nude

male

figure1; the navel is indicated by a raised disc. On the

statue with

the contracting base, which is one of the best, the surface modelling

of the

elbowjoint is clearly shown. The orbital cavity in the figures on

Raraku is

rather differently modelled from those on the ahu; in the statues on

the

mountain the position of the eyeball is always indicated by a straight

line

below the brow, the orbit has no lower border (fig. 72). On the

terraces the

socket is constantly hollowed out as in the figure at the British

Museum (fig.

31).

The eye

is the only point in which the two sets vary, with the important

exception that

some on the mountain have a type of back which never appears on the

ahu. This

question of back proved to be of special interest: in some images it

remained

exactly as when the figure left the quarry, the whole was convex,

giving it a

thick and archaic appearance, particularly as regards the neck; in

other

instances, the posterior was beautifully modelled after the same

fashion as

those on the terraces, the stone had been carefully chipped away till

the ears

stood out from the back of the head, the neck assumed definite form,

and the

spine, instead of standing out as a sharp ridge, was represented by an

incised

line. This second type, when excavated, proved, to our surprise, to

possess a

well-carved design in the form of a girdle shown by three raised bands,

this

was surmounted by one or sometimes by two rings, and immediately

beneath it was

another design somewhat in the shape of an M (figs. 64 and 106). The

whole was

new, not only to us, but to the natives, who greatly admired it. Later,

when we

knew what to look for, traces of the girdle could be seen also on the

figures

on the ahu where the arm had protected it from the weather. It was

afterwards

realised with amusement that the discovery of this design might have

been made

before leaving England by merely passing the barrier and walking behind

the

statues in the Bloomsbury portico. One case was found, a statue at

Anakena,

where a ring was visible, not only on the back but also on each of the

buttocks, and in view of subsequent information these lower rings

became of

special importance. The girdle in this case consisted of one line only;

the

detail of the carving had doubtless been preserved by being, buried in

the sand

(fig. 65) . The two forms of back, unmodelled and modelled, stand side

by side

on the mountain (figs. 66, 67).

The next

step was to discover where and when the modelling was done. Certainly

not in

the original place in the quarry, where it would be impossible from the

position in which the image was evolved; generally speaking there was

no trace

of such work, and it was not until many months later that new light was

thrown

on the matter. Then it was remarked that in one of the standing statues

on the

outside of the hill, which was buried up to the neck (fig. 59), while

the right

ear was most •carefully modelled, showing a disc, the left ear was as

yet quite

plain, and that the back of the head also was not symmetrical.

Excavations made

clear that the whole back was in course of transformation from the

boat-shaped

to the modelled type, each workman apparently chipping away where it

seemed to

him good (fig. 68). Two or three similar cases were then found on which

work

was proceeding; but on the other hand, some of the simpler backs were

excavated

to the foot, and others a considerable distance, and there was no

indication

that any alteration was intended. There are three possible explanations

for these-erect

and partially moulded statues: Firstly, it may have been the regular

method for

the back to be completed after the statue was set up, in which case

some kind

of staging must have been used; one of our guides had made a remark,

noted, but

not taken very seriously at the moment, that "the statues were set up

to

be finished"; some knowledge or tradition of such work, therefore,

appeared to linger. Secondly, the convex back may be the older form,

and those

on which work was being done were being modelled to bring them up to

date.

Alteration did at times take place; a certain small image presented a

very

curious appearance both from the proportion of the body, which was

singularly

narrow from back to front, and because it was difficult to see how it

remained

in place as it was apparently exposed to the base; it turned out that

the

figure had been carved out of the head of an older statue, of which the

body

was buried below (no. 14, fig. 60). Thirdly, these particular figures

may have

been erected and left in an unfinished condition; if so, their

deficiencies

were high up and would be obvious

BACKS OF STANDING

STATUES, RANO RARAKU

FIG. 66. —Unmodelled

FIG. 66. —Unmodelled

FIG. 67. —Modelled

EXCAVATED

STATUES

FIG. 67. —Modelled

EXCAVATED

STATUES

FIG. 68. — Showing

back in process of being

modelled.

[No.

23. Fig. 50]

FIG. 68. — Showing

back in process of being

modelled.

[No.

23. Fig. 50]

FIG. 69. — Showing

image wedged by boulders

FIG. 69. — Showing

image wedged by boulders

Scamping

did not often occur, and when it did so it was in the concealed

portions. In

one case the left hand was correctly modelled, but the right was not

even

indicated beyond the wrist (fig. 63). The statue shown in the

frontispiece,

which rejoices in the name of Piro-piro, meaning "bad odour,"2

stands at the foot of the slope, and appears to remain as it was set up

without

further burial. It is a well-made figure, probably one of the most

recent, and

the upper part of the back is carefully moulded, but on digging it out

it was

found that the bottom had not been finished, but left in the form of a

rough

excrescence of stone; there was no ring, but a girdle had been carved

on the

protruding portion, so that this was not intended to be removed. In

another

instance a large head had fallen on a slope at such an angle that it

was

impossible to locate the position of the body; curiosity led to

investigation,

when it was found that the thing was a fraud, the magnificent head

being

attached to a little dwarf trunk, which must have been buried

originally nearly

to the neck to keep the top upright. These instances of "jerrybuilding"

confirm our impression that at any rate a large number of the statues

were

intended to remain in situ.

Indications

were found of two different methods of erection, and the mode may have

been

determined by the nature of the ground. By the first procedure the

statue seems

to have been placed on its face in the desired spot, and a hole to have

been

dug beneath the base. The other method was to undermine the base, with

the

statue lying face uppermost; in several instances a number of large

stones were

found behind the back of the figure, evidently having been used to

wedge it while

it was dragged to the vertical. The upright position had sometimes been

only

partially attained; one statue was still in a slanting attitude,

corresponding

exactly to the slope of a hard clay wall behind it; the interval

between the

two, varying from three yards to eighteen inches, had been packed with

sub-angular boulders which weighed about one hundredweight, or as much

as a man

could lift (fig. 69) .

A few of

the figures bear incised markings rudely, and apparently promiscuously,

carved.

This was first noted in the case of one of two statues which stand

together

nearest to the entrance of the crater; here it has been found possible

to work

the rock at a low level, and in the empty quarry, from which they no

doubt have

been taken, two images have been set up, one slightly in front of the

other;

six still unfinished figures lie in close proximity (figs. 70 and 71).

The

standing figure, nearest to the lake, bore a rough design on the face,

and when

it was dug out the back was found to be covered with similar incised

marks. The

natives were much excited, and convinced that we should receive a large

sum of

money in England when the photograph of these was produced, for nothing

ever

dispelled the illusion that the expedition was a financial speculation.

It was

these carvings more especially that we ourselves hastily endeavoured to

cover

up when, on the arrival of Admiral von Spec's Squadron, we daily

expected a

visit from the officers on board. The markings have certainly not been

made by

the same practised hand as the raised girdle and rings, and appear to

be

comparatively recent (fig. 64). Other statues were excavated, where

similar

marks were noticed, but, except in this case, digging led practically

always to

disappointment. It was the part above the surface only which had been

used as a

block on which to scrawl design, from the same impulse presumably as

impels the

school-boy of to-day to make marks with chalk on a hoarding. On one ahu

the top

of the head of a statue has been decorated with rough faces, the

carving

evidently having been done after the statue had fallen.

In

digging out the image with the tattooed back, we came across the one

and only

burial which was found in connection with these figures; it was close

to it and

at the level of the rings. The long bones, the patella, and base of the

skull

were identified; they lay in wet soil, crushed and intermixed with

large

stones, so the attitude could not be determined beyond the fact that

the head

was to the right of the image and the long bones to the left. These

bones had

become of the consistency of moist clay, and could only be identified

by making

transverse sections of them with a knife, after first cleaning portions

longitudinally by careful scraping.

FIG. 70. — TWO

IMAGES ERECTED IN QUARRY.

FRONT VIEW.

Prior to excavation.

[Nos.

108-109. Fig

47]

FIG. 70. — TWO

IMAGES ERECTED IN QUARRY.

FRONT VIEW.

Prior to excavation.

[Nos.

108-109. Fig

47]

FIG. 71. — TWO

IMAGES ERECTED IN QUARRY.

BACK VIEW.

After excavation.

[Nos. 109-108. Fig

47. See also Fig. 64.]

FIG. 71. — TWO

IMAGES ERECTED IN QUARRY.

BACK VIEW.

After excavation.

[Nos. 109-108. Fig

47. See also Fig. 64.]

In

several other instances human bones were discovered near the statues,

but, like

the carvings, they appeared to be of later date than the images. One

skull was

found beneath a figure which was lying face downwards on the surface;

another

fragment must have been placed behind the base after the statue had

fallen

forward. The natives stated that in the epidemics which

ravaged the island the statues afforded a

natural mark for depositing remains. In the same way a head near an

ahu, which

was at first thought to be that of a standing statue, turned out to be

broken

from the trunk and put up pathetically to mark the grave of a little

child.

There is a roughly constructed ahu on the outside of Rano Raraku at the

corner

nearest to the sea, of which more will be said hereafter, and a

quarried block

of rock on the very top of the westerly peak was also said to be used

for the

exposure of the dead (no. 75, fig. 47). Close to this block there are

some very

curious circular pits cut in the rock; one examined was 5 feet 6 inches

in

depth and 3 feet 6 inches in diameter (no. 74, fig. 47). It is possible

they

were used as vaults, but, if so, the shape is quite different from

those of the

ahu. The conclusion arrived at was that the statues themselves were not

directly connected with burials. There seems also no reason to believe

that

they are put up in any order or method; they appear to have been

erected on any

spot handy to the quarries where there was sufficient earth, or even,

as has

been seen, in the quarry itself when circumstances permitted.

The South-Eastern Side of

Rano Raraku is a

problem in itself. The great wall formed by the cliff is like the

ramparts of

some giant castle rent by vertical fissures. The greatest height, the

top of

the peak, is about five hundred feet, of which the cliff forms perhaps

half,

the lower part being a steep but comparatively smooth bank of detritus.

Over

the grassy surface of this bank are scattered numerous fragments of

rock,

weighing from a few pounds to many tons, which have fallen down from

above. The

kitchen tent in our camp at the foot had a narrow escape from being

demolished

by one of these stones, which nearly carried it away in the impetus of

its

descent. It has never been suggested that this face of the mountain was

being

worked, nevertheless, it was subsequently difficult to understand how

we lived

so long below it, gazing at it daily, before we appreciated the fact

that here

also, although in much lesser degree, were both finished and embryo

images. At

last one stone was definitely seen to be in the form of a head, and

excavation

showed it to be an erected and buried statue. A few other figures were

found

standing and prostrate, and some unfinished images; these last,

however, were

in no case being hewn out of solid rock, but wrought into shape out of

detached

stones. On the whole, it is not probable that this portion was ever a

quarry,

in the same way as the western side and the interior of the crater. It

is, of

course, impossible to say what may be hidden beneath the detritus, but

the

lower part of the cliff is too soft a rock to be satisfactorily hewn,

and the

workmen appear simply to have seized on fragments which have fallen

from above.

“Here," they seem to have said, “is a good stone; let us turn it into a

statue."

One day,

when making a more thorough examination of the slope, our attention was

excited

by a small level plateau, about half-way up, from which protruded two

similar

pieces of stone next to one another. They were obviously giant noses of

which

the nostrils faced the cliff. Digging was bound to follow, but it

proved a long

business, as the figures it revealed were particularly massive and

corpulent.

Their position was horizontal, side by side, and the effect, more

particularly

when looking down at them from the cliff above, was of two great bodies

lying

in their graves (fig. 73). The thing was a mystery; they were certainly

not in

a quarry, but if they had once been erect, why had they faced the

mountain,

instead of conforming to the rule of having their back to it?

Orientation could

not account for it, as other statues on the same slope were differently

placed.

Then again, if they had once stood and then fallen, and in proof of

this one

head was broken off from the trunk, how did it come about that they

were lying

horizontally on a sloping hill-side? The upper part of the bodies had

suffered somewhat

from weather, and a small round basin, such as natives use for domestic

purposes, had been hollowed out in one abdomen, but the hands were

quite sharp

and unweathered. We used to scramble up at off moments, and stand

gazing down

at them trying to read their history.

It became

at last obvious they had once been set up with the lower part inserted

in the

ground to the usual level, and later been intentionally thrown down.

For this

purpose a level trench must have been cut through the sloping side of

the hill

at a depth corresponding to the base of the standing images, and into

this the

figures had fallen. While they lay in the trench with the upper part of

the

bodies exposed, one had been found a nice smooth stone for household

use. A

charcoal soil level showed clearly where the surface had been at this

epoch,

which must have been comparatively recent, as an iron nail was found in

it.

Finally, a descent of earth had covered all but the noses, leaving them

in the

condition in which we found them.

This,

though a satisfactory explanation as far as it went, did not account

for the

fact that the figures were facing the mountain, and here for once

tradition

came to our help. These images had, it was said, marked a boundary; the

line of

demarcation led between them, from the fissure in the cliff above right

down to

the middle statue in the great Tongariki terrace. To cross it was

death; but as

to what the boundary connoted no information was forthcoming; there

seemed no

great tribal division — the same clans ranged over the whole of the

district.

When, however, the line is followed through the crevice into the crater

(fig.

47), it is found to form on both sides the boundary where the

image-making

ceased (no. i is a detached figure being brought down, not in a

quarry), and

was probably the line of taboo which preserved the rights of the

image-makers.

I was later given the cheering information that a certain "devil"

frequented the site of my house, which was just on the image side of

the

boundary, who particularly resented the presence of strangers, and was

given to

strangling them in the night. The spirits, who inhabit the crater, are

still so

unpleasant, that my Kanaka maid objected to taking clothes there to

wash, even

in daylight, till assured that our party would be working within call.

FIG. 72. — EXCAVATED

STATUE.

South-east side,

Rano Raraku. Showing form of

hands.

FIG. 72. — EXCAVATED

STATUE.

South-east side,

Rano Raraku. Showing form of

hands.

Isolated Statues. — The

finished statues, as distinct from those in the quarries, have so far

been

spoken of under two heads, those which once adorned the ahu and those

still

standing on the slope of Raraku; there is, however, another class to

consider,

which, for want of a better name, will be termed the Isolated Statues.

It has

already been stated that, as Raraku is approached, a number of figures

lie by

the side of the modern track, others are round the base of the

mountain, and

yet other isolated specimens are scattered about the island. All these

images

are prostrate and lie on the surface of the ground, some on their backs

and

some on their faces. These were the ones which, according to legend,

were being

moved from the quarries to the ahu by the old lady when she stopped the

work in

her wrath; or, according to another account, quoted by a visitor before

our day,

“They walked, and some fell by the way."

FIG. 73 — PROSTRATE

STATUES, SOUTH-EASE SIDE,

RANO RARAKU, AFTER EXCAVATION.

FIG. 73 — PROSTRATE

STATUES, SOUTH-EASE SIDE,

RANO RARAKU, AFTER EXCAVATION.

|

| FIG 74. |

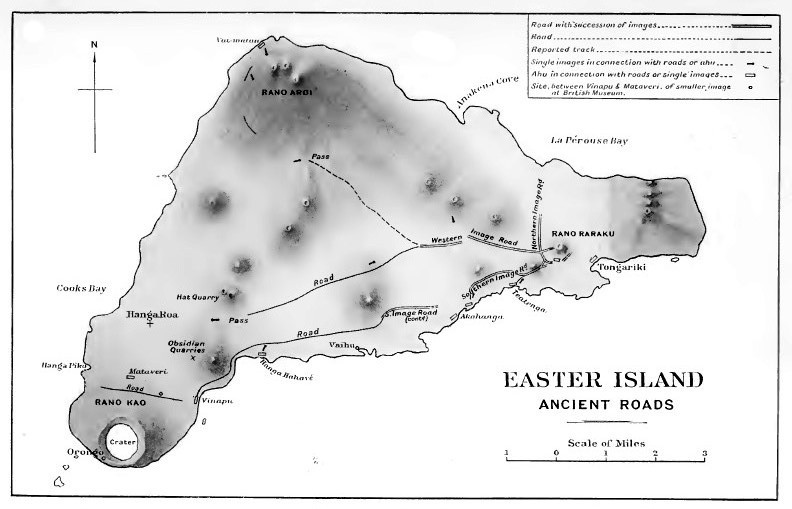

There

must, we felt, have been roads along which they were taken, but for

long we

kept a look-out for such without success. At last a lazy Sunday

afternoon ride,

with no particular object, took one of us to the top of a small hill,

some two

miles to the west of Raraku. The level rays of the sinking sun showed

up the

inequalities of the ground, and, looking towards the sea, along the

level plain

of the south coast, the old track was clearly seen; it was slightly

raised over

lower ground and depressed somewhat through higher, and along it every

few

hundred yards lay

a

statue. Detailed study confirmed this first impression. At times over

hard stony ground the trail was lost, but its main drift was

indisputable; it was about nine feet or ten feet in width, the

embankments were

in places two feet above the surrounding ground, and the cuttings three

feet

deep. The road can be traced from the south-western corner of the

mountain,

with one or two gaps, nearly to the foot of Rano Kao, but the

succession of

statues continues only about half the distance. It generally runs some

few

hundred yards further inland than the present road, but a branch, with

a statue,

leads down to the ahu of Teatenga on the coast, and, another portion,

either a

branch or a detour of the main road, also with a statue, goes to the

cove of

Akahanga with its two large image ahu (fig. 32). There are on this road

twenty-seven statues in all, covering a distance of some four miles,

but

fourteen of them, including two groups of three, are in the first mile.

Their

heights are from fifteen feet to over thirty feet, but generally over

twenty

feet.

As a clue

had now been obtained, it was comparatively simple to trace two other

roads

from Raraku. One leads from the crater, and connects it with the

western

district of the island. It commences at the gap in the mountain wall,

in the

centre of which an image lies on its face with weird effect, as if

descending

head foremost into the plain; and runs for a while roughly parallel to

the

first road but about a mile further inland. It is not quite so regular

as the

south road, and is marked for a somewhat less distance by a sequence of

images,

some fourteen in number, which in the same way grow further apart as

the

distance from the mountain increases. When the succession of statues

ceases,

the road divides; one track turns to the north-west, and reaches the

sea-board

through a small pass in the western line of cones; the other continues

as far

as a more southerly pass in the same succession of heights. In each

pass there

is a statue.

The third

road, which runs from Raraku in a northerly direction, is much shorter

than

those to the south and west. It has only four statues covering a

distance of

perhaps a mile, and it then disappears; if, however, the figures round

the base

of the mountain belonged to it, and they lie in the same direction, it

started

from the southern corner of the mountain, led in front of the standing

statues

and across the trail from the crater, before taking its northward route

up the

eastern plain. The furthest of the images is the largest which has been

moved;

it lies on its back, badly broken, but the total of the fragments gives

a height

of thirty-six feet four inches. In addition to these three avenues,

there are

indications that some of the statues on the south-eastern side of

Raraku may

have been on a fourth road along that side beneath the cliff.

FIG. 75. — AN IMAGE

ON ITS BACK.

Unbroken; if erect,

would face westwards.

FIG. 76. — AN IMAGE

ON ITS FACE.

Showing by cleavage

and only partial fall

that it

has been erect and

faced westwards.

So far

the matter was sufficiently clear, but another problem was still

unsolved: if the

images were really being moved to their respective ahu all round the

coast, how

was it that, with very few exceptions, they were all found in the

neighbourhood

of Raraku? If also they were being moved, what was the method pursued,

for some

lay on their backs and some on their faces? With the hope of

elucidating this

great question of the means of transport, we dug under and near one or

two of

the single figures without achieving our end — nothing was found; but

the close

study which the work necessitated called attention to the fact that on

one of

them the lines of weathering could not have been made with the figure

in its

present horizontal attitude. The rain had evidently collected on the

head and

run down the back; it must therefore have stood for a considerable time

in a

vertical position. It was again a noticeable fact that, though some

single

figures are lying unbroken (fig. 75), others, like the large one on the

north

road, proved to be so shattered that no amount of normal disintegration

or

shifting of soil could account for their condition — they had obviously

fallen.

So wedded, however, were we at this time to the theory that they were

in course

of transport, that it was seriously considered whether they could have

been

moved in an upright position. The point was settled by finding one day

by the

side of the track, some two miles from the mountain, a partially buried

head.

This was excavated, and a statue found that had been originally set up

in a

hole and, later, undermined, causing it to fall forward. This was the

only

instance of an isolated figure where the burial had been to any depth,

but in

various other cases it was then seen that soil had been removed from

the base,

and one or two more of the figures had not quite fallen (fig. 76).

When the

whole number of the statues on the roads were in imagination

re-erected, it was

found that they had all originally stood with their backs to the hill.

Rano

Raraku was, therefore, approached by at least three magnificent

avenues, on

each of which the pilgrim was greeted at intervals by a stone giant

guarding

the way to the sacred mountain (map of roads). One of the ahu on the

south

coast, Hanga Paukura, has been approached by a similar avenue of five

statues

facing the visitor. These five images when first seen were a great

puzzle, as

some of them are so embedded in the earth that their backs are even

with the

levelled sward in front of the ahu; later there seemed little doubt

that, like

the two giants on the southeast side of Raraku, trenches had been dug

into

which they had fallen. Subsequently, a sixth statue was discovered, the

other

side of a modern

wall, weathered and worn away, but of Raraku stone and still upright.

This is

the only instance of an erect figure to be found elsewhere than on the

mountain

(fig. 77).

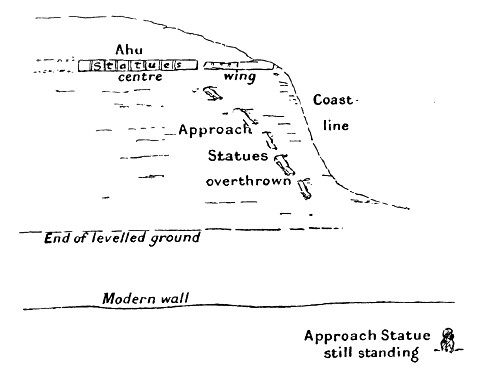

FIG. 77. — DIAGRAM

SHOWING CEREMONIAL AVENUE

OF AHU HANGA PAUKURA.

FIG. 78. — AHU PARO,

With image which

was the last to be

overthrown.

Foreground. —

Hillock, traditionally utilised

for placing the crown in position.

Distance. — Eastern Headland, with three

cones, from which Spanish sovereignty was proclaimed in 1770.

In

addition to the images which have stood in these processional roads,

there are,

excluding one or two figures near the mountain whose raison

d’être is somewhat doubtful, fourteen isolated statues in

various parts of the island, for whose position no certain reason could

be

found. Some of these may have belonged to inland ahu which have

disappeared, or

they may be solitary memorials to mark some particular spots, but the

greater

number appear to have stood near tracks of some sort. Some of these

last may

have been boundary stones, and in this class may perhaps fall the

smaller

statue now at the British Museum, which is a very inferior specimen.

According

to local information it stood almost half-way on the track leading from

Vinapu

to Mataveri along the bottom of Rano Kao; the hole from which it was

dug was

pointed out, and our informant declared that he remembered it standing,

and

that the people used to dance round it. The larger figure at the

British Museum

was in a unique position, which will be spoken of later.

No

statues were, therefore, found of which it could be said that they were

in

process of being removed, and the mode of transport remains a mystery.

An image

could be moved down from the quarry by means of banks of earth, and

though

requiring labour and skill, the process is not inconceivable.

Similarly, the

figures may have been, and probably were, erected on the terraces in

the same

way, being hauled up on an embankment of earth made higher than the

pedestals

and then dropped on them. Near Paro, the ahu where the last statue was

overthrown, there is a hillock, and tradition says that a causeway was

made

from it to the head of the tall figure which stood upon the ahu, and

along this

the hat was rolled (fig. 78) — a piece of lore which seems hardly

likely to

have been invented by a race having no connection with the statues. But

the

problem remains, how was the transport carried out along the level? The

weight

of some amounted to as much as 40 or 50 tons. It would simplify matters

very

much if there were any reason to suppose that the images were moved, as

was the

case with the hats, before being wrought, merely as cylinders of stone,

in

which case it would be possible to pass a rope under and over it, thus

parbuckling the stone or rolling it along, but the evidence is all to

the

contrary. There is no trace whatever of an unfinished image on or near

an ahu,

while, as we have seen, they are found at all stages in the quarry.

Presumably

rollers were employed, but there appears never to have been much wood,

or

material for cordage, in the island, and it is not easy to see how

sufficient

men could bring strength to bear on the block. Even if the ceremonial

roads

were used when possible, these fragile figures have been taken to many

distant

ahu, up hill and down dale, over rough and stony ground, where there is

no

trace of any road at all.

The

natives are sometimes prepared to state that the statues were thrown

down by

human means, they never have any doubt that they were moved by

supernatural

power. We were once inspecting an ahu built on a natural eminence, one

side was

sheer cliff, the other was a slope of 29 feet, as steep as a house

roof, near

the top a statue was lying. The most intelligent of our guides turned

to me

significantly. “Do you mean to tell me," he said, “that that was not

done

by mana?” The darkness is not

rendered less tantalising by the reflection that could centuries roll

away and

the old scenes be again enacted before us, the workers would doubtless

exclaim

in bewildered surprise at our ignorance, “But how could you do it any

other way?”

Besides

the ceremonial roads and their continuations, there are traces of an

altogether

different track which is said to run round the whole seaboard of the

island. It

is considered to be supernatural work, and is known as Ara Mahiva,

"ara" meaning road and "Mahiva" being the name of the

spirit or deity who made it. On the southern side it has been

obliterated in

making the present track — it was there termed the "path for carrying

fish";

but on the northern and western coasts, where for much of the way it

runs on

the top of high cliffs, such a use is out of the question. It can be

frequently

seen there like a long persistent furrow, and where its course has been

interrupted by erosion, no fresh track had been made further inland; it

terminates suddenly on the broken edge, and resumes its course on the

other

side. It is best seen in certain lights running up both the western and

southern edges of Rano Kao. Its extent and regularity appeared to

preclude the

idea of landslip. There is no reason to suppose that it is due to the

imported

livestock, and it has no connection with ahu, or the old native centres

of

population, yet to have been so worn by naked feet it must constantly

have been

used. This silent witness to a forgotten past is one of the most

mysterious and

impressive things on the island.

FIG 79. THE CRATER FROM WHICH THE HATS OF THE IMAGES

WERE HEWN, ON THE SIDE OF THE HILL PUNAPAU.

Rano Kao in the

distance.

FIG. 80. AN UNFINISHED HAT NEAR THE QUARRY.

FIG. 81. A FINISHED HAT AT AHU HANGA O-ORNU; OTHERS IN

THE DISTANCE.

STONE CROWNS

OF THE IMAGES

Mention

must finally be made of the crowns or hats which adorned the figures on

the

ahu. Their full designation is said to be "Hau (hats) hiterau moai,"

but they are always alluded to merely as "hiterau" or "hitirau."

These

coverings for the head were cylindrical in form, the bottom being

slightly

hollowed out into an oval depression in order to fit on to the head of

the

image; the depression was not in the centre, but left a larger margin

in front,

so that the brim projected over the eyes of the figure, a fashion

common in

native head-dresses. They are said by the present inhabitants to have

been kept

in place by being wedged with white stones. The top was worked into a

boss or

knot. The material is a red volcanic tuff found in a small crater on

the side

of a larger volcano, generally known as Punapau, not far from Cook's

Bay (fig.

79). In the crater itself are the old quarries. A few half-buried hats

may be

seen there, and the path up to it, and for some hundreds of yards from

the foot

of the mountain, is strewn with them. They are at this stage simply

large cylinders,

from 4 feet to 8 feet high, from 6 feet to 9 feet across (fig. 80), and

they

were obviously conveyed to the ahu in this form and there carved into

shape

(fig. 81). An unwrought cylinder is still lying at a hundred yards from

the ahu

of Anakena. The finished hats are not more than 3 feet 10 inches to 6

feet in

height, with addition of 6 inches to 2 feet for the knob; the

measurement

across the crown is from about 5 feet 6 inches to 8 feet. The stone is

more

easily broken and cut than that of the statues, and while many crowns

survive,

many more have been smashed in falling or used as building materials.

It is a

noteworthy fact that the images on Raraku never had hats, nor have any

of the

isolated statues; they were confined to those on the ahu.

1 The sole

possible exception was probably due to some flaw in the stone.

2 The

farthest outstanding figure to the left in fig. 46

|