| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2015 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER

XVI NATIVE CULTURE IN PRE-CHRISTIAN TIMES (continued) Religion — Position of the Miru Clan — The Script — The Bird Cult — Wooden Carvings. RELIGION The

religion of the Islanders, employing the word in our sense, seems

always to

have been somewhat hazy,1 and the difficulty in grasping it

now is

increased by the fact that since becoming Roman Catholics they dislike

giving

the name of "atua," or god, to their old deities; it only drops out

occasionally. They term them "aku-aku," which means spirits, or more

frequently "tatane," a word of which the derivation is obvious. The

confusion of ideas was crystallised by a native, who gravely remarked

that they

were uncertain whether one of these beings was God or the Devil, so

they "wrote

to Tahiti, and Tahiti wrote to Rome, and Rome said he was not the

Devil, he was

God"; a modern view being apparently taken at headquarters of the

evolution of religious ideas. Both these words, tatane and aku-aku,

will be employed

for supernatural beings, without prejudice to their original character,

or

claims to divinity; some of them were certainly the spirits of the

dead, but

had probably become deified; the ancestors of Hotu-matua were reported

to have

come with him to the island. They existed in large numbers, being both

male and

female, and were connected with different parts of the island; a list

of about

ninety was given, with their places of residence. No worship was paid,

and the

only notice taken of these supernatural persons was to mention before

meals the

names of those to whom a man owed special duty, and invite them to

partake; it

was etiquette to mention with your own the patron of any guest who was

present.

There was no sacrifice; the invitation to the supernatural power was

purely

formal, or restricted to the essence of the food only. Nevertheless,

the

aku-aku, in this at least being human, were amiable or the reverse

according to

whether or not they were well fed. If they were hungry, they ate women

and

children, and one was reported as having a proclivity for stealing

potatoes;

if, on the contrary, they were well-disposed to a man, they would do

work for

him, and he would wake in the morning to find his potato field dug,

which, as

our informant truly remarked, was "no like Kanaka." The

aku-aku appeared in human form, in which they were indistinguishable

from

ordinary persons. One known as Ukao-hoheru looked like a very beautiful

woman,

and was the wife of a young Tupahotu who had no idea she was really a

tatane.

She lived with him at Mahatua on the north coast, and bore him a child.

One

very wet day she was obliged to leave the house to take fresh fire to

the

cooking-place where it had gone out. When she returned, her husband was

angry

that she had no red paint on her face, and, not heeding her explanation

that

the rain had washed it off, took a stick to beat her. She ran away, and

he

followed, till at last she sat down on the edge of the eastern

headland, where

there is now an ahu known by her name. When by and by he came up, she

told him

to go back and look after the child, and fled away like a rushing

whirlwind

over the sea and was no more seen. Two other

female tatane are reported to have lived together in a cave on the

cliff-side

of Paréhé,2 whose names were Kava-ara and Kava-tua. They

heard all

men tell of the beauty of a certain Uré-a-hohove, a young man who lived

near

Hanga Roa; so they went down to see him, put him to sleep, and carried

him on

his mat up to their cave, where they left him. Before going away they

told an

old woman, also an aku-aku, that she was not to go and look into the

cave. This

she naturally proceeded to do, and, finding Uré, warned him to eat

nothing the

two tatane might give to him, supplying him herself with some chicken.

When therefore

his captors came back and offered him food, he only pretended to take

it, and

ate the chicken instead. They then went away again. The old woman came

back,

and said, “If cockroaches come, kill them; if flies come, kill them;

but if a

crab comes, do not kill it." Uré did as he was told, and killed the

cockroaches and flies, which were other tatane; but the crab he did not

kill,

it was the old woman. Meanwhile for many days the father of Uré wept

for him,

till some men sailing under the cliff while fishing, heard a song, and

looking

up saw the missing man; but they would not go and fetch him, though the

father

gave them much food, for the cliff was steep and the cave difficult to

reach.

At last a woman volunteered for the task, and was lowered over the

cliff in a

net, and by this means succeeded in fetching Uré safely to the top. The

history

ends with his return to his home, and does not mention if, in correct

fashion,

he married his fair deliverer. Aku-aku

were not immortal. A man called Raraku, after whom the mountain is said

to have

been named, caught a big "heke," which seems to have been an octopus,

in the sea near Tongariki and ate it, with the result that he went mad,

and all

people gave chase to him. He caught up a wooden lizard (fig. 117), and,

using

it as a club, ran amok among tatane across the north shore and down the

west

coast, killing them right and left; the names of twenty-three were

given who

thus met their fate. Human

beings, on the other hand, were liable to be attacked by tatane, more

particularly at night, when there was risk, not only to their bodies,

but also

to their own spirits,3 which were at large while they slept.

It is

still firmly believed that in dreams the soul visits any locality

present to

the thought. On one of the ahu is a rough erection of slabs, said to be

the

house of the aku-aku Mata-wara-wara, or "Strong-Rain." He had as a

partner another aku-aku called Papai-a-taki-vera, and they arranged

between

them that Mata should bring on rain, while Papai constructed a house of

reeds

which was only there at night; then when the spirits of sleeping

people, which

were wandering abroad, became cold with the rain, they went into the

house and

the tatane killed them. The unfortunate sleeper waked in the morning

feeling

distinctly unwell, he lingered on for two or three days, and then died.

It was

not essential to life to have a soul, but you could not really get on

comfortably without it. No knowledge survives of any belief or ideas

with

regard to a future state. The spirit, it was said, appeared

occasionally for

five or ten years after a man's death and then vanished. Pan in

the shape of tatane is by no means dead. Not only do such beings haunt

the

crater of Rano Raraku, but tales are told of weird apparitions at dusk

which

vanish mysteriously into space. There

were no priests, but certain men, known as "koromaké," practised

spells which would secure the death of an enemy, and there was also the

class

known as "ivi-atua," which included both men and women. The most

important of these ivi-atua, of whom it was said there might be perhaps

ten in

the island, held commune with the aku-aku, others were able to

prophesy, and

could foresee the whereabouts of fish or turtle, while some had the

gift of

seeing hidden things, and would demand contributions from a secreted

store of

bananas or potatoes, in a way which was very disconcerting to the

owner. There was

practically only one religious function of a general nature; it was

very

popular and had a surprising origin. Attention was attracted on the

south coast

by a particularly long stoep of rounded pebbles measuring 139 feet, and

obviously connected with a thatched house now disappeared. That, our

guides

said in answer to a question, “is a haré-a-té-atua, where they praised

the

gods." "What gods?” "The men who came from far away in ships.

They saw they had pink cheeks, and they said they were gods." The early

voyagers, for the cult went back at least three generations, were

therefore

taken for deities in the same way as Cook was at Hawaii. The simplest

form of

this celebration took place on long mounds of earth known as

"miro-o-orne,"

or earth-ships, of which there are several in the island, one of them

with a

small mound near it to represent a boat. Here the natives used to

gather

together and act the part of a European crew, one taking the lead and

giving

orders to the others. A more formal ceremony was held in a large house.

This

had three doors on each side by which the singers entered, who were up

to a

hundred in number, and ranged themselves in lines within; in one house,

of

which a diagram was drawn, a deep hole was dug in the middle, at the

bottom of

which was a gourd covered with a stone to act as a drum. On the top of

this a

man danced, being hidden out of sight in the hole. In other

cases, two, or perhaps three, boats were constructed inside the house,

the

masts of which went through the roof; these boats were manned with

crews clad

in the garments of European sailors, the gifts from passing vessels

being kept

as stage properties. Fresh music was composed for every occasion, and

in one

song, which was quoted, much reference is made to the "red face of the

captain from over the seas." The position of chief performer was one of

great honour, being analogous, on a glorified scale, to the leader of a

cotillon of our own day. It was stated by an old man that his

great-grandfather

had so acted, and even the words sung were still remembered. Te Haha, a

Miru

(fig. 83), gave us to understand that he had been a great social

success in his

youth, and counted up three koro, and seven hare-ate-atua at which he

had been

present. As he was a handsome old man, and was connected with the court

of the

chief Ngaara, his pride of recollection was very probably justified.

Juan,

mixing up, no doubt, recollections of a later date, gave a vivid

representation

on one of these spots of the pseudo-captain striding about and using

very

strong language, while he called upon the engineer to "make more smoke

so

that the ship should go fast." On the

border-line, between religion and magic, wherever, if anywhere, that

line

exists, was the position of the clan known as the Miru. Members of this

group

had, in the opinion of the islanders, the supernatural and valuable

gift of

being able to increase all food supplies, especially that of chickens,

and this

power was particularly in evidence after death. It has been known that

certain

skulls from Easter are marked with designs, such as the outline of a

fish;

these are crania of the Miru, and called "puoko-moa," or fowl-heads,

because they had, in particular, the quality of making hens lay eggs

(fig. 96).

Hotu, the Miru, whose mother, it may be remembered, was the victim of a

cannibal feast, made his own skull an heirloom, as "it was so extremely

good for chickens," that he did not wish it to go out of the family.

His

son gave it to a relative, who was the father of an old man from whom

we managed

to obtain it. When the time came to hand it over to us, the late owner

began to

cling to it affectionately, and say that he "wept much at the thought

of

its going to England"; as, however, the bargain had already been

completed, we remained obdurate, and at the time of writing Hotu

resides with

Ko Tori at the Royal College of Surgeons. The Miru

were unique in other ways; they were the only group which had a headman

or

chief, who was known as the "ariki," or sometimes as the

"ariki-mau," the great chief, to distinguish him from the

"ariki-paka," a term which seems to have been given to all other

members of the clan. The office of ariki-mau was hereditary, and he was

the

only man who was obliged to marry into his own clan.4 It was

customary when he was old and feeble that he should resign in favour of

his

son. There are various lists of the succession of chiefs, counted from

the

first immigrant, Hotu-matua . The oldest lists are those given by

Bishop

Jaussen5 and by Admiral Lapelin,6 which contain

some

thirty names. Thomson gives one with fifty-seven. In our day there was

admittedly much uncertainty about the sequence, but the number was said

to be

thirty,7 and two independent lists were obtained. All these

categories differ, though they contain many of the same names,

particularly at

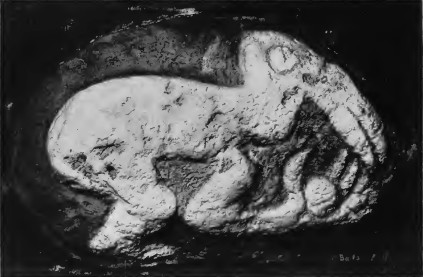

the beginning and end.  [Butterworth] FIG. 96. — A MIRU SKULL WITH INCISED DESIGN. The last

man to fill the post of ariki with its original dignity was Ngaara; he

died

shortly before the Peruvian raid, and becomes a very real personage to

anyone

inquiring into the history of the island. He was short, and very stout,

with

white skin, as had all his family, but so heavily tattooed as to look

black. He

wore feather hats of various descriptions, and was hung round both back

and

front with little wooden ornaments, which jingled as he walked. When

our

authorities can remember him his wife was dead and he lived with his

son

Kaimokoi. It was not permitted to see them eat, and no one but the

servants was

allowed to enter the house. His headquarters were at Anakena, the cove

on the

island where, according to tradition, the first canoe landed. It is

unique in

having a sandy shore, and is surrounded by an amphitheatre of low

hills. Behind

it to the west rises the high central ground of the island, beyond it,

on the

other side, is the eastern plain; it thus approximately terminates the

strip of

land held by the Miru (fig. 97). There are now at Anakena the remains

of six

ahu, a few statues, and the foundations of various houses. Ngaara held

official

position for the whole island, but he was neither a leader in war, nor

the

fount of justice, nor even a priest; he can best be described as the

custodian

of certain customs and traditions. The act most nearly approaching a

religious

ceremony was conducted under his auspices, though not by him

personally. In

time of drought he sent up a younger son and other ariki-paka to a

hill-top to

pray for rain: they were painted on one side red, on the other black

with a

stripe down the centre. These prayers were addressed to Hiro, said to

be the

god of the sky, a supernatural being in whom we seem getting nearer the

idea of

a divinity, as distinct from a spirit of the dead, and of whom we would

gladly

have learnt more than could be discovered.  FIG. 97. — ANAKENA COVE. Hill on left terraced summit. The

ariki-paka had other duties besides praying for rain; they made "mam,"

or strings of white feathers tied on to sticks, which they placed among

the

yams to make them grow. They buried a certain small fish among the

sugar-canes

to bring up the plants, and when a koro was being held, and it was

consequently

particularly desirable that the fowls should thrive, an ariki-paka

painted a

design in red, known as the “rei-miro," below the door of the

chicken-house (fig. 115). Te Haha,

the "social success," who was an ariki-paka in the entourage of

Ngaara, gave graphic descriptions of life at Anakena when he was a boy.

If, he

said, people wanted chickens, they applied to the Ariki-mau, who sent

him with

maru, and his visits were always attended with satisfactory results. Ngaara

never consumed rats, and one day, coming across the boy watching rats

being

cooked, he was extremely angry, for it transpired that, if Te Haha ha(i

eaten

them, his power for producing chickens would have diminished;

presumably

because he would have imbibed ratty nature, which was disastrous to

eggs and

young chickens. The Ariki, however, made himself useful to him on

occasion. The

younger Miru had long hair reaching to his heels, and one day, when he

was

asleep in a cave, some one cut it off. So he went to Ngaara, who told

him to

bring ten coconuts, which he broke and put in pieces of the sacred

tree, “ngau-ngau";

the spell blasted the offender, who promptly died. Ngaara himself

attended the

inauguration of any house of importance. The wooden lizards were put

formally

on each side of the entrance to the porch, and the Ariki and an

ivi-atua, who

"went with him like a tatane," were the first to eat in the new

dwelling: only the houses with stone foundations were thus honoured.

The Ariki

was visited one month in the year by "all people," who brought him

the plant known as pua on the end of sticks, put the pua into his

house, and

retired backwards. He also

held receptions on other occasions, seated on the broken-off head of an

old

image, which was pointed out on a grassy declivity among the hills

behind

Anakena; these were special occasions for criticising the tattoo. Those

who

were well tattooed were sent to stand on one hill slope, whilst those

who were

badly done were sent to another; the Ariki and men behind him laughed

contemptuously at the latter, which, as the process was permanent and

could not

be altered, seems slightly unkind. These receptions were also attended

by men

who had made boats, and by twins, to whom the Ariki gave a "royal

name." Such children were not, as in so many countries, considered

unlucky,

but it was necessary that at birth they should live in a house apart,

otherwise

they would not survive. This superstition still exists. Shortly before

our

arrival a woman in the village had given birth to twins, for whom a

little

grass house was put up; another woman went in and brought them out to

the

mother to nurse. Closely

connected with the subject of the Miru clan is that of the method of

writing.

While we can only catch glimpses of the. image cult through the mists

of antiquity,

the tablets, known as "kohau-rongo-rongo,"8 were an

integral part of life on the island within the memory of men not much

past

middle age (fig. 98). The highest authority on them was the ariki

Ngaara. It

was tantalising to feel how near we were to their translation and yet

how far.

Te Haha had begun to learn to write, but found that his hand shook too

much,

besides, as he explained, Ngaara used "to send him to the chickens."

Juan had had the offer of learning one form of such script, but, not

unnaturally, had looked upon it with some contempt, preferring European

accomplishments. The information which could be gathered was,

therefore, with

one exception, which will be noted later, simply that of the layman, or

man in

the street, who had been aware of the existence of the art and seen it

going on

around him, but had no personal knowledge. The

tablets were of all sizes up to 6 feet. It was a picturesque sight to

see an old

man pick up a piece of banana-stem, larger than himself, from among the

grove

in which we were talking, and stagger along with it to show what it

meant to

carry a tablet, though, as he explained, the sides of the tablet were

flat, not

round like the stem. It is said that the original symbols were brought

to the

island by the first-comers, and that they were on "paper," that when

the paper was done, their ancestors made them from the banana plant,

and when

it was found that withered they resorted to wood. Every clan had

professors in

the art who were known as rongo-rongo men ("tangata-rongo-rongo").

They had houses apart, the sites of which are shown in various

localities. Here

they practised their calling, often sitting and working with their

pupils in

the shade of the bananas; their wives had separate establishments. In

writing,

the incision was made with a shark's tooth: the beginners worked on the

outer

sheaths of banana-stems, and later were promoted to use the wood known

as

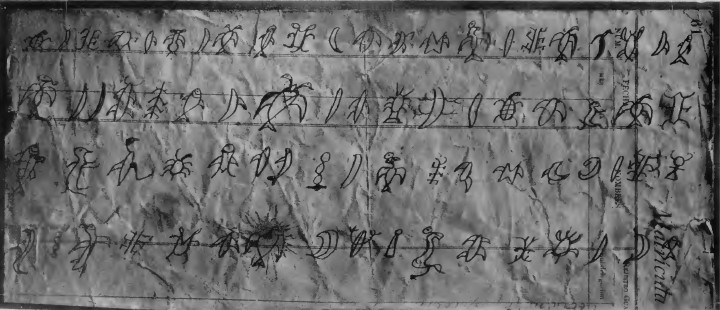

"toro-miro."9  [Brit. Mus.] FIG. 98 — PORTION OF AN INCISED TABLET (Kohau-rongo-rongo) The

glyphs are, as will be seen, so arranged that when the figures of one

row are

right way up, those of the one immediately below it are on their heads;

thus

only alternate rows can, at the same time, be seen in correct position

(fig.

98). The method of reading was, according to Te Haha, to read one row

from left

to right, then come back reading the next from right to left, the

method known

as boustrophedon, from the manner in which an ox ploughs a furrow. The

finished

ones were wrapped in reeds and hung up in the houses. According to two

independent

authorities they could only be touched by the professors or their

servants, and

were taboo to the uninitiated, which, however, does not quite agree

with other

statements, nor with that of the missionaries that they were to be

found in

"every house." They were looked upon as prizes to be carried off in

war, but they were often burnt with the houses in tribal conflict. Ngaara is

said to have had "hundreds of kohau" in his house, and instructed in

the art, which he had learnt from his grandfather. He is described,

with a

vivid personal touch, as teaching the words, holding a tablet in one

hand and

swaying from side to side as he recited. Besides giving instruction, he

inspected the candidates prepared by other professors, who were

generally their

own sons; he looked at their kohau and made them read, on which he

either

passed them, clapping if they did well, or turned them back. Their

sponsors

were made personally responsible. If the pupils acquitted themselves

creditably, presents of kohau were made to the teachers; if the youth

failed,

the tablets of the instructor were taken away. Every

year there was a great gathering of rongo-rongo men at Anakena,

according to Te

Haha, as many as several hundreds of them came together. The younger

and more

energetic of the population assembled from all districts in the island

to look

on. They brought "heu-heu" (feathers on the top of sticks), tied pua

on to them, and stuck the sticks in the ground all round the place. The

inhabitants of the neighbouring districts brought offerings of food to

Ngaara,

that he should be able to supply the multitude, and the oven was "five

yards along." The gathering was near the principal ahu, midway between

the

sandy shore and the background of hills. The Ariki and his son Kaimokoi

sat on

seats made of tablets, and each had a tablet in his hand; they wore

feather

hats, as did all the professors. The rongo-rongo men were arranged in

rows,

with an alley-way down the centre to the Ariki. Some of them had

brought with

them one tablet only; others as many as four. The old ones read in

turn, or

sometimes two together, from the places where they stood, but their

tablets

were not inspected. Te Haha and his comrades stood on the outskirts,

and he and

one other lad held maru in their hands. If a young man failed, he was

called up

and his errors pointed out; but if an old man did not read well, Ngaara

would

beckon to Te Haha, who would go up to the man and take him out by the

ear. Our

informant repeated this part of the story identically months later, and

added

that the Ariki would say to the culprit, “Are you not ashamed to be

taken out

by a child?"; the offender's hat was taken away, but the tablet was not

inspected. The

entire morning was spent in hearing one half of the men read; there was

an

interval at midday for a meal, after which the remainder recited, the

whole

performance lasting till evening. Fights occasionally ensued from

people scoffing

at those who failed. Ngaara would then call Te Haha's attention to it,

and the

boy would go up to the offenders with the maru in his hand and look at

them,

when they would stop and there would be no more noise. "When the

function

was over, the Ariki stood on a platform borne by eight men and

addressed the

rongo-rongo men on their duties, and doing well, and gave them each a

chicken.

Another old man, Jotefa, gave a different account of the great

assembly, by

which the Ariki sat on his stoep and the old men stood before him and

"prayed"; according to this version they either did not bring their

tablets or their doing so was voluntary. In addition to the great day,

there

were minor assemblies at new moon, or the last quarter of the moon,

when the

rongo-rongo men came to Anakena. The Ariki walked up and down reading

the

tablets, while the old men stood in a body and looked on. Ngaara

used also to travel round the island, staying for a week or two in

different

localities with the resident experts. Another savant on the south coast

was

said to be "too big a man to have a school," and also went about

visiting and inspecting learned establishments in the same manner. Ngaara,

before the end, fell on evil days. The Ngaure clan was in the

ascendancy, and

carried off the Miru as slaves; the Ariki was taken to Akahanga on the

south

coast with his son, Kaimokoi, and grandson, Maurata. They were there

five years

in captivity, and the "Miru cried much"; at the end of that time the

clan united with the Tupahotu and rescued the old man. He was then ill,

and

died not long afterwards at Tahai, on the west coast, near Hanga Roa,

while

living with his daughter, who had married a Marama. For six days after

his

death everyone worked at making the sticks with feathers on the top

(heu-heu),

and they were put all round the place. He was buried in the ruined

image ahu at

Tahai, his body being carried on three of the tablets, and followed

through a

lane of spectators by the rongo-rongo men; the tablets were buried with

him.

His head paid the penalty of its greatness, and was subsequently

stolen; its

whereabouts was unknown. Ten or fifteen of his tablets were given to

old men;

the rest went to a servant, Pito, and on his death to Maura ta. When

Maurata

went to Peru, Také, a relative of Te Haha, obtained them, and Salmon

asked Te

Haha to get hold of them for him. Také, however, unfortunately owed Te

Haha a

grudge, because when Te Haha was in Salmon's service, and consequently

well

off, he did not give him as many presents as his relative thought

should have

been forthcoming, and he consequently refused to surrender them. They

were

hidden in a cave whose general locality was surmised, but Také died

without

making known the exact site, and they could never be found. Kaimokoi's

tablets

were burnt in war. The

question remains what were the subjects with which the tablets dealt,

and in

what manner did they record them? Various attempts have been made to

deal with

a problem which will probably never be wholly solved. Twice before our

own day

native assistance has been sought to decipher them. It will be

remembered that

the existence of these glyphs was first reported by the missionaries;

but even

at that time, when volunteers were asked for who could translate them,

none

came forward. Bishop Jaussen, Vicaire Apostolique of Tahiti, managed to

find in

that island a native of Easter among those brought there to work on the

Brander

plantations, who was supposed to understand them, and who read them

after the

boustrophedon method. From the information given by him, the Bishop was

satisfied that the signs represented different things, such as sun,

stars, the

ariki, and so forth, and has given a list of the figures and their

equivalent.

At the same time he held that each one was only a peg on which to hang

much

longer matter which was committed to memory. The other attempt to

obtain a

translation was that of Paymaster Thomson, of U.S.S. Mohican,

in 1886. There was then living an old man, Ure-vae-iko by

name, who was said to be the last to understand the form of writing; he

declined to assist in deciphering them on the ground that his religious

teachers had said it would imperil his soul. Photographs, however, were

shown,

and, by the aid of stimulants, he was induced to give a version of

their

meaning, the words of which were taken down by Salmon. It was, however,

remarked that when the photographs were changed, the words proceeded

just the

same. Inquiries

were made by the Expedition about this old man, and it was agreed by

the

islanders that he had never possessed any tablets nor could he make

them, but

that he had been a servant of Ngaara and had learnt to repeat them.

Before

leaving the island we went with the old men through the five

translations given

by Thomson. Of three nothing was known; one which describes the process

of

creation was recognised as that of a kohau, but looked at a little

askance, as

there were Tahitian words in it. The last was laughed out of court as

being

merely a love-song which everyone knew. Our own

early experiences had resembled those of the Americans. Photographs of

tablets,

which were produced merely to elicit general information, were to our

surprise

promptly read, certain words being assigned to each figure; but after a

great

deal of trouble had been taken, in drawing the signs and writing down

the

particular matter, it was found that any figure did equally well. The

natives

were like children pretending to read and only reciting. It was noted,

however,

with interest, that in perhaps half a dozen cases different persons

recited

words approximately the same, beginning, “He timo te ako-ako, he

ako-ako

tena," and on inquiry it was said that they were derived from one of

the

earliest tablets and were generally known. It was "like the alphabet

learned first"; Uré-vai-iko had stated that they were the "great old

words," all others being only "little ones." To get any sort of

translation was a difficult matter, to ask for it was much the same as

for a

stranger solemnly to inquire the meaning of some of our own old nursery

rhymes,

such as "Hey diddle diddle, the cat and the fiddle" — some words

could be explained, others could not, the whole meaning was unknown. It

seems

safe, however, to assume that at least we have here the contents of one

of the

old tablets. With

regard to other kohau, a list was obtained of the subjects with which

they were

believed to deal. These amounted to thirteen in all, most of the names

being

given by several different persons. We have seen that there was a kohau

of the

"Ika," the murdered men; this was known to only one professor, who

taught it to a pupil, and the two divided the island between them, the

master

taking the west and north coast to Anakena and the pupil the remainder.

A

connected, or possibly the same, tablet was made at the instance of the

relatives of the victim and helped to secure vengeance. Certain kohau

were said

to be lists of wars: some dealt with ceremonies, and others formed part

of

ceremonies themselves. They were in evidence at koro, where Ngaara and

the

professors used to come and "pray for the father," and a woman went

on to the roof of the house holding the "Kohau-o-te-pure" (prayer

tablet). In another case, a woman who wished to honour her

father-in-law, and

at the same time secure fertility, set up a pole round which she walked

holding

a child and a tablet, given her by Ngaara, while he and other

rongo-rongo men

who brought their kohau at his order stood by and sang. Perhaps

the most interesting tablet was one known as the "Kohauo-te-ranga."

The story was told to us sitting on the foundation of a house on the

east side

of Raraku, the aspect which is not quarried. This house, it was said,

had been

the abode of two men, who were old when the informant was a boy, and

who taught

the rongo-rongo; some days ten students would come, other days fifteen.

The

wives and children of the old men lived in another house lower down the

mountain. One of the experts, Arohio by name, was a Tupahotu, and had

as a

friend another member of the same clan called Kaara. Kaara was servant

to the

Ariki, and had been taught rongo-rongo by him, and Ngaara, trusting him

entirely, gave into his care this most valuable kohau known as "ranga."

It was the only one of the kind in existence, and was reported to have

been

brought by the first immigrants; it had the notable property of

securing

victory to its holders, in such a manner that they were able to get

hold of the

enemy for the "ranga" — that is, as captives or slaves for manual

labour. Kaara, anxious to obtain the talisman for his own clan, stole

the kohau

and gave it to Arohio, who kept it in this house. When Ngaara asked for

it, the

man said that it was at Raraku, but before the Ariki could get hold of

it,

Arohio sent it back to Kaara, and these two thus sent it backwards and

forwards

to one another, lying to Ngaara when needful. The Ariki seems to have

taken a

somewhat feeble line, and, instead of punishing his servant, merely

tried to

bribe him, with the result that he never again saw his kohau. The son

of Arohio

sold it to one of the missionaries, and it is presumably one of those

which

went to Tahiti. The matters with which it would naturally have been

supposed

that the rongo-rongo would deal, such as genealogies, lists of ariki,

or the

wanderings of the people, were never mentioned. We were

fortunately just in time to come across a man who had been able to make

one

species of glyphs, though he was no longer, alas! in the hey-day of his

powers.

We were shown one day in the village a piece of paper taken from a

Chilean

manuscript book, on which were somewhat roughly drawn a number of

signs, some

of them similar to those already known, others different from any we

had seen

(fig. 99). They were found to have been derived from an old man known

as

Tomenika. He was, by report, the last man acquainted with an inferior

kind of

rongo-rongo known as the "tau," but was now ill and confined to the

leper colony. We paid a visit to him armed with a copy of the signs,

but found

him inside his doorway, which it was obviously undesirable to enter,

and

disinclined to give help; he acknowledged the figures as his work,

recited

"He timo te ako-ako," and explained some of the signs as having to do

with "Jesus Christ." The outlook was not promising. Another

visit, however, was paid, this time with Juan's assistance, and though

the old

man appeared childish, and the natives frankly said that "he had lost

his

memory," things went better. He was

seated on a blanket outside his grass-hut, bare-legged, wearing a long

coat and

felt hat; he had piercing brown eyes, and in younger days must have

been both

good-looking and intelligent. He asked if we wanted the tau, and

requested a

paper and pencil. The former he put on the ground in front of him

between his

legs, and took hold of the pencil with his thumb above and first finger

below;

he made three vertical lines, first of noughts then of ticks, gave a

name to

each line, and proceeded to recite. There was no doubt about the

genuineness of

the recitation, but he gabbled fast, and when asked to go slowly so

that it

could be taken down, was put out and had to begin again; he obviously

used the

marks simply to keep count of the different phrases. At the end of the

visit he

offered to write something for next time. We left some paper with him,

and on

our return two or three days later he had drawn five lines

horizontally, of

which four were in the form of the glyphs, but the same figure was

constantly

repeated, and there were not more than a dozen different symbols in

all. It was

said by the escort to be "lazy writing." Tomenika complained that the

paper was not "big enough," so another sheet was given, which was put

by the side of the first and the lines continued in turn horizontally.

He drew

from left to right rapidly and easily. Unfortunately, it did not seem

wise to

touch the paper, but the writing was copied, by looking over it as he

went on,

with the sincere hope that his blanket did not contain too many

inhabitants of

some infectious variety. The recitation was partly the same as on the

previous

occasion, the signs taking the place of ticks; anything from three or

four to

ten words were said to each sign. If he made a variation when asked to

repeat,

it was in transposing the order of two phrases; evidently the signs

themselves

were not to him, now at any rate, connected with particular words. When we

subsequently went with our escort into the meaning of the words, it was

found

that the latter half of each phrase generally consisted of one of the

lower numericals

preceded by the word “tau," or year — thus, “the year four," "the

year five," etc.; the numbers, roughly speaking, ran in order of

sequence

up to ten, recommencing with each line. The first part of the phrase

was

generally said to be the name of a man, but of this it was difficult to

judge,

as children were called after any object or place; thus "flowering

grass" might be the name of a thing, or of a place, or of a man called

after either the object or the locality. Happily,

one of the most reliable old men, Kapiera by name, had at one time

lived with

Tomenika, who was said to have been in those days always busy writing;

and he

was able to explain the general bearing of the tau. When a koro was

made in

honour of a father, an expert was called in to commemorate the old

man's deeds,

“how many men he had killed, how many chickens he had stolen," and a

tablet was made accordingly. There was, in addition, a larger tablet

containing

a list of these lesser ones, and giving merely the name of each hero

and the

year of his koro. It would read somewhat thus, “James the year four,

Charles

the year five," and so forth, going up to the year ten, when the

numbers

began again. If there were two koro in a year, they came under the same

numeral. It was this general summary which had been recited by

Tomenika, and,

though there was a certain amount of confusion, each line seems to have

represented a decade. In addition, as will be seen, “James" and

"Charles

" each had a kohau of their own. Kapiera

was able to give a specimen of the lesser tau; it illustrates

interestingly the

general method of condensation in which, even in the recitations, a few

words

assume or implicate extended knowledge. It ran thus, “Of Kao the year

nine," "Ngakurariha the eldest"; then come five men's names

followed by the name of a fish; then a doubtful word; then "that side

island my place." "I see Ngakurariha at the koro." The story, as

explained, was that Kao, a man of Vinapu on the south coast, and

Ngakurariha,

his eldest son, went to Mahatua on the north side and stayed with the

five men

whose names are given, who were brothers, and learnt from them the tau.

Having

done this, they proceeded to murder them, and went and took a fish,

then returned

to Rano Kao, made a koro and the tau. The tau

was, it was said, originally made by an ancestor of the first immigrant

chief,

Hotu-matua; it was not taboo in the same way as the other rongo-rongo,

and was

not known to Ngaara. There were, about the beginning of last century,

only

three personages acquainted with it. One was Omatohi, a Tupahotu, whose

son,

Tea-a-tea, was Tomenika's foster-father and instructor in the art. It

was said

by Tomenika himself and by others that he "only knew part," and there

were other signs with which he was not acquainted, for his

foster-father had

died before he knew all. A great

effort was subsequently made to get further information from Tomenika,

more

particularly as to the exact method of writing, but he was back in his

hut very

ill, and all conversation had once more to be done through the doorway.

Every

way that could be thought of was tried to elicit information, but

without real

success. He did draw two fresh symbols, saying first they were "new"

and then "old," and stating they represented the man who gave the

koro, but "there was no sign meaning a man." "He did not know

that for ariki, the old men did," "the words were new, but the

letters were old," "each line represented a koro." An attempt to

get him to reproduce any tau made by himself was a failure. The

answers, on the

whole, were so wandering and contradictory, that after a second visit

under

those conditions, making five in all, the prospect of getting anything

further

of material value did not seem sufficient to justify the risks

toothers,

however slight. As the last interview drew to a close, I left the hut

for a

moment, and leant against the wall outside, racking my brains to see if

there

was any question left unasked, any possible way of getting at the

information;

but most of what the old man knew he had forgotten, and what he dimly

remembered he was incapable of explaining. I made one more futile

effort, then

bade him good-bye and turned away. It was late afternoon on a day of

unusual

calm, everything in the lonely spot was perfectly still, the sea lay

below like

a sheet of glass, the sun as a globe of fire was nearing the horizon,

while

close at hand lay the old man gradually sinking, and carrying in his

tired

brain the last remnants of a once-prized knowledge. In a fortnight he

was dead.  FIG. 99. — TOMENIKA’S SCRIPT. No

detailed systematic study of the tablets has as yet been possible from

the

point of view of the Expedition, but it seems at present probable that

the

system was one of memory, and that the signs were simply aids to

recollection,

or for keeping count like the beads of a rosary. To what extent the

figures

were used at will, or how far each was associated with a definite idea

it is

impossible to say. Possibly there was no unvarying method; certain ones

may

conveniently have been kept for an ever-recurrent factor, as the host

in the

tau, and in well-known documents, such as "he timo te ako-ako," they

would doubtless be reproduced in orthodox succession. But in the

tablets which

we possess the same figures are continually repeated, and the fact that

equivalents were always having to be found for new names, as in that of

the

fish-man, or ika, suggest that they may have been largely selected by

the

expert haphazard from a known number. As Tomenika said, “the words were

new,

but the letters were old," or to quote Kapiera to the same effect, they

were "the same picture, but other words." It will be noted how few

men are reported to have known each variety of rongo-rongo, and that

while

Ngaara looked at the tablets of the boys, apparently to see if they

were

properly cut, it was in the recitation only of the older men that

accuracy was

insisted on. The names which Bishop Jaussen's informant assigned to

some five

hundred figures may or may not be accurate, but whether the native or

anyone

else could have stated what the signs conveyed is another matter. It is

easy to

give the term for a knot in a pocket-handkerchief, but no one save the

owner

can say whether he wishes to remember to pay his life insurance or the

date of

a tea-party. In trying

to enter into the state of society and of mind which evolved the

tablets there

are two points worth noticing. Firstly, the Islanders are distinctly

clever

with their hands and fond of representing forms. Setting aside the

large

images, the carving of the small wooden ones is very good, and the

accuracy of

the tablet designs is wonderful. Then they have real enjoyment in

reciting

categories of words; for example, in recounting folktales, opportunity

was

always gleefully taken of any mention of feasting to go through the

whole of

the food products of the island. In the same way, if a hero went from

one

locality to another, the name of every place en route

would be rolled out without any further object than the

mere pleasure of giving a string of names. This form of recitation

appears to

affect them aesthetically, and the mere continuation of sound to be a

pleasure.

Given, therefore, that it was desired to remember lists of words,

whether

categories of names or correct forms of prayer, the repetition would be

a

labour of love, and to draw figures as aids to recollection would be

very

natural. Nevertheless,

the signs themselves have no doubt a history, which as such, even apart

from

interpretation, may prove to be signposts in our search for the origin

of this

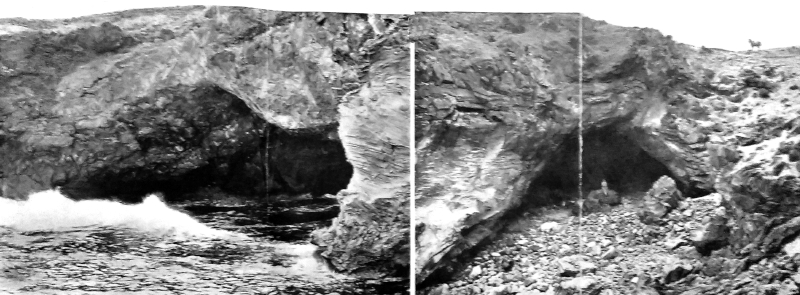

mysterious people. Knowledge of the tablets was confined to a few, and formed a comparatively small element of life in the island; the whole of social existence revolved round the bird cult, and it was the last of the old order to pass away. The main object of the cult was to obtain the first egg of a certain migratory sea-bird, and the rites were connected with the western headland, Rano Kao. Little has yet been said of this volcano, but, from the scenic point of view, it is the most striking portion of the island. Its height is 1,300 feet, and it possesses a crater two-thirds of a mile across, at the bottom of which is a lake largely covered with weeds and plant-life. On the eastward, or landward face, the mountain, as already explained, slopes downward with a smooth and grassy incline, and the other three sides have been worn by the waves into cliffs over 1,000 feet in height. On the outermost side the sea has nearly forced its way into the crater itself; and the ocean is now divided from the lake at this point by only a narrow edge, along which it would be possible but not easy to walk with safety. At some near date, as geological ages reckon, the island will have a magnificent harbour (figs. loo and io8) . Off this part of the coast are three little islets, outlying portions of the original mountain, which have as yet withstood the unceasing blows of the ocean. Their names are Motu Nui, Motu Iti, and Motu Kao-kao, and on them nest the sea-birds which have for unknown centuries played so important a part in the history of the island. On the mainland, immediately opposite these islets, there is on the top of the cliff a deserted stone village; it is known as Orongo, and in it the Islanders awaited the coming of the birds. It consists of nearly fifty dwellings arranged in two rows, both facing the sea, and partly overlapping; the lower row terminates just before the narrowest part of the crater wall is reached. The final houses are built among an outcrop of rocks; they are betwixt two groups of stones, and have in front of them a small natural pavement. The stones nearest the cliff look as if at any moment they might join their brethren in headlong descent to the shore below (fig. 103) . Both the upstanding rocks and pavement are covered with carvings; some of them are partly obliterated by time, and can only be seen in a good light, but the ever-recurrent theme is a figure with the body of a man and the head of a bird; portions of the carvings are covered by the houses, and they therefore antedate them.  FIG. 102. — PAINTINGS ON ROOF OF ANA KAI-TANGATA. Top, a bird superimposed on a European ship. The whole

position is marvellous, surpassing the wildest scenes depicted in

romance.

Immediately at hand are these strange relics of a mysterious past; on

one side

far beneath is the dark crater lake; on the other, a thousand feet

below,

swells and breaks the Pacific Ocean, it girdles the islets with a white

belt of

foam, and extends, in blue unbroken sweep, till it meets the ice-fields

of the

Antarctic. The all-pervading stillness of the island culminates here in

a

silence which may be felt, broken only by the cry of the sea-birds as

they

circle round their lonely habitations.  FIG. 103. — ORONGO, END HOUSES AND CARVED ROCKS. The stone

village formed the scene of some of our earliest work during our first

residence at the manager's house; for some weeks, weather permitting,

we rode

daily up the mountain, an ascent which took about fifty minutes, and

spent the day

on the top studying the remains, and picking the brains of our native

companions. Some of the houses have been destroyed in order to obtain

the

painted slabs within, but most are in fair, and some in perfect,

preservation.

The form of construction suitable to the low ground has perhaps been

tried here

and abandoned, for some of the foundation-stones, pierced with the

holes to

support the superstructure of stick and grass, are built into the

existing

dwellings. The present buildings (fig. 104) are well adapted to such a

wind-swept spot; they are made of stone laminć, with walls about 6 feet

thick;

the inside walls are generally lined with vertical slabs, and

horizontal slabs

form the roof. The greater number are built at the back into rising

ground, and

their sides and top are covered with earth; the natives call them not

"hare," or houses, but "ana," or caves. Where space permits

it, the form is boat-shaped, but some have been adapted to natural

contours.10 The

dwellings vary in shape and size, from 52 feet by 6 feet to 8 feet by 4

feet;

the height within varies from 4 feet to over 6 feet, but it is the

exception to

be able to stand upright. In some cases they open out of one another,

and not

unfrequently there is a hatch between two through which food could be

passed.

The doorway, with its six foot of passage, is just large enough to

admit a man.

Into each of them, armed with ends of candles, we either crawled on

hands and

knees, or wriggled like serpents, according to our respective heights.

The

slabs lining the wall, which are just opposite the doorway, and thus

obtain a

little light, are frequently painted; some of them have bird and others

native

designs, but perhaps the most popular is a European ship, sometimes in

full

sail, and once with a sailor aloft in a red shirt (fig. 105). Inside

the houses

we found the fiat, sea-worn boulders which are used as pillows and

often

incised with rough designs; there were also a few obsidian spear heads,

or

mataa, and once or twice sphagnum from the crater, which was used for

caulking

boats, and also as a sponge to retain fresh water when at sea. Outside

many of

the doors are small stone-lined holes, which we cleared out and

examined. They

measure roughly rather under 2 feet across by some 15 inches in depth.

Our guides

first told us that they were "ovens," but, as no ash was found, it

seems probable that their second thoughts were right, and they were

used to contain

stores. The groups of dwellings have various names, and are associated with the particular clans, who, it is said, built them. One house, which stands near the centre of the village, Taurarenga by name, is particularly interesting as having been the dwelling of the statue Hoa-haka-nanaia, roughly to be translated as "Breaking wave," now resident under the portico of the British Museum (fig. 31). Lying about near by were two large stones, which had originally served as foundations for the thatched type of dwelling, but had apparently been converted into doorposts for the house of the image; on one of them a face had been roughly carved (fig. 107). The statue is not of Raraku stone, and it will be realised how entirely exceptional it is to find a statue under cover and in such a position. The back and face were painted white, with the "tracings" in red. The bottom contracts, and was embedded in the earth, though a stone suspiciously like a pedestal is built into a near wall. The house had to be broken down in order to get the figure out. According to the account of the missionaries, three hundred sailors and two hundred Kanakas were required to convey it down the mountain to H.M.S. Topaze in Cook's Bay. The memory of the incident is fast fading, but our friend Viriamo repeated in a quavering treble the song of the sailors as they hauled down their load.11 The figure is some eight feet high and weighs about four tons.  FIG. 104. — CENTRAL PORTION OF ORONGO VILLAGE. Left, house which contained image; centre, three houses opening on small quadrangle; right, canoe-shaped house with double entrance. Day by

day, as we worked, we gazed down on the islets. The outermost, which,

as its

name Motu Nui signifies, is also the largest, is more particularly

connected

with the bird story, which we were gradually beginning to grasp, and at

last

the call to visit it could no longer be resisted (fig. 109). It was not

an easy

matter, for Mana was away; the boats

of the natives left a good deal to be desired in the way of

seaworthiness, and

it was only possible to make the attempt on a fine day. Finally, on

arrival at

the island, it required not a little agility to jump on to a ledge of

rocks at

the second the boat rose on the crest of the waves, before it again

sank on a

boiling and surging sea till the heads of the crew were many feet below

the

landing-place. We managed, however, between us to get there three times

in all.

Once, when I was there without S., there was an anxious moment on

re-embarking.

No one quite knew what happened. Some of the crew said that the gunwale

of the

boat, as she rose on a wave, caught under an overhanging shelf of rock,

others

were of the opinion that the sudden weight of the last man, who at that

moment

leapt into the boat, upset her balance; anyway, this tale was very

nearly never

written. Once landed on the island, the surface is comparatively level

and

presents no difficulties; it is about five acres in extent, the greater

part is

covered with grass, and in every niche and cranny of the rock are

seabirds'

nests. By a large bribe of tobacco one of the most active old men was

induced

to accompany us, and to point out the sites of interest. Later, we

followed up

the story at Raraku, and so little by little at many times, in divers

places,

and from various people was gathered the story of the bird cult which

follows. The

fortunate clan, or clans, for sometimes several combined, left nothing

to

chance; in fact, as soon as one year's egg had been found, the incoming

party

made sure of their right of way by taking up their abode at the foot of

Rano

Kao — namely, at Mataveri. Here there were a number of the large huts

with

stone foundations; in these they resided, with their wives and

families. One of

our old gentlemen friends first saw the light in a Mataveri dwelling,

when his

people were in residence, or, to use the proper phraseology, when his

clan were

"the Ao."13 This name "ao" is also given to a

large paddle, as much as 6 feet in length, used principally, if not

exclusively, in connection with bird rites and dancing at Mataveri. In

some

specimens a face is fully depicted on the handle; in others the

features have

degenerated to a raised line merely indicating the eyebrows and nose.

There are

pictures of it on slabs in the Orongo houses, in which the face is

adorned with

vertical stripes of red and white after the native manner, as described

by the

early voyagers (figs. 105 and 118). Not many

sea-birds frequent this part of the Pacific, but on Motu Nui some seven

species

find an abiding-place. Some stay for the whole year, some come for the

winter,

and yet others for the summer. Among the last is a kind known to the

natives as

manu-tara12; it arrives in September, the spring of the

southern

hemisphere. The great object of life in Easter was to be the first to

obtain

one of the newly laid eggs of this bird. It was too solemn a matter for

there

to be any general scramble. Only those who belonged to the clan in the

ascendancy for the time being could enter on the quest. Sometimes one

group

would  I.  II. FIG. 105. — PAINTED SLABS FROM HOUSES AT ORONGO. I. Two pictorial representations of ao. II. A face adorned with paint. A European ship. [Height of slabs, 3 ft. to 3 ft. 6 in.] keep it

in their hands for years, or they might pass it on to a friendly clan.

This

selection gave rise, as might be expected, to burnings of hearts; the

matter

might be, and probably often was, settled by war. One year the Marama

were

inspired with jealousy because the Miru had chosen the Ngaure as their

successors, and burnt down the house of Ngaara. This was, perhaps, the

beginning of the fray when the old Ariki was carried off captive.  [W. A. M.& Co.] [Brit. Mus.] FIG. 106. — BACK OF STATUE FROM ORONGO. Showing raised ring and girdle, also incised figures of bird-man, ao, and Ko-Mari. (For front of statue, see fig. 31.)  FIG. 107. — CARVED DOOR-POST, ORONGO. Naturally

the months passed at Mataveri were occupied by the residents in

feasting as

well as in dancing, and equally naturally the victims were human. It

was to

grace one of these gatherings, when the Ureohei were the Ao, that the

mother of

Hotu, the Miru, was slain in a way which he considered outraged the

decencies

of life, and it was in revenge for another Mataveri victim that the

last

statues were thrown down. It is told that the destined provender for

one meal evaded

that fate by hiding in the extreme end of a hut, which was so long and

dark

that she was never found. Some of these repasts took place in a cave in

the

sea-cliff near at hand. Here the ocean has made great caverns in a wall

of

lava, into which the waves surge and break with booming noise and

dashing

spray. The recess which formed the banqueting-hall is just above

high-water

mark, and is known as "Ana Kai-tangata," or Eat-man Cave (fig. 102).

The roof is adorned with pictures of birds in red and white; one of

these birds

is drawn over a sketch of a European ship, showing that they are not of

very

ancient date (fig. 103). When July

approached, the company, or some of them, wound their way up the

western side

of the hill, along the ever-narrowing summit to the village of Orongo;

the path

can just be traced in certain lights, and is known as the "Road of the

Ao." They spent their time while awaiting the birds in dancing each day

in

front of the houses; food was brought up by the women, of whom Viriamo

was one.

The group of houses at the end among the carved rocks was taboo during

the

festival, for they were inhabited by the rongo-rongo men, the western

half

being apportioned to the experts from Hotu Iti, the eastern to those

from

Kotuu. "They chanted all day; they stopped an hour to eat, that was

all." They came at the command of Ngaara, but it is noteworthy that he

himself .never appeared at Orongo, though he sometimes paid a friendly

call at

Mataveri. A short

way down the cliff immediately below Orongo is a cave known as

"Haka-rongo-manu," or "listening for the birds"; here men

kept watch day and night for news from the islet below. The

privilege of obtaining the first egg was a matter of competition

between

members of the Ao, but the right to be one of the competitors was

secured only

by supernatural means. An "ivi-atua," a divinely gifted individual,

of the kind who had the gift of prophecy, dreamed that a certain man

was

favoured by the gods, so that if he entered for the race he would be a

winner,

or, in technical parlance, become a bird-man, or "tangata-manu." The

victor, on being successful, was ordered to take a new name, which

formed part

of the revelation, and this bird-name was given to the year in which

victory

was achieved, thus forming an easily remembered system of chronology.

The

nomination might be taken up at once or not for many years; if not used

by the

original nominee, it might descend to his son or grandson. If a man did

not

win, he might try again, or say that "theivi-atua was a liar," and

retire from the contest. Women were never nominated, but the ivi-atua

might be

male or female, and, needless to say, was rewarded with presents of

food. There

were four "gods" connected with the eggs — Hawa-tuu-take-take, who

was "chief of the eggs," and Make-make, both of whom were males;

there were also two females. Vie Hoa, the wife of Hawa, and Vie

Kenatea. Each

of these four had a servant, whose names were given, and who were also

supernatural beings. Those going to take the eggs recited the names of

the gods

before meat, inviting them to partake.  FIG. 108 — RANO KAO FROM MOTU NUI.  FIG. 109. — MOTU NUI AND MOTU ITI. The

actual competitors were men of importance, and spent their time with

the

remainder of the Ao in the stone houses of the village of Orongo; they

selected

servants to represent them and await the coming of the birds in less

comfortable quarters in the islet below. These men, who were known as

"hopu,"

went to the islet when the Ao went up to Orongo, or possibly rather

later. Each

made up his provisions into a "pora," or securely bound bundle of

reeds; he then swam on the top of the packet, holding it with one arm

and

propelling himself with the remaining arm and both legs. An

incantation, which

was recited to us, was said by him before starting. In one instance,

the

ivi-atua, at the same time that he gave the nomination, prophesied that

the

year that it was taken up a man should be eaten by a large fish. The

original

recipient never availed himself of it, but on his death-bed told his

son of the

prophecy. The son, Kilimuti, undeterred by it, entered for the race and

sent

two men to the islet; one of them started to swim there with his pora,

but was

never heard of again, and it was naturally said that the prophecy had

been

fulfilled. Kilimuti wasted no regret over the misfortune, obtained

another

servant, and secured the egg; he died while the Expedition was on the

island. The hopu

lived together in a large cave of which the entrance is nearly

concealed by

grass. The inside, however, is light and airy; it measures 19 feet by

13, with

a height of over 5 feet, and conspicuous among other carvings in the

centre of

the wall is a large ao more than 7 feet in length. A line dividing the

islet

between Kotuu and Hotu Iti passed through the centre of the cave, and

also

through another cave nearer the edge of the islet; in this latter there

was at

one time a statue about 2 feet high known as Titahanga-o-te-henua, or

The

Boundary of the Land.14 As bad weather might prevent fresh

consignments of food during the weeks of waiting, the men carefully

dried on

the rocks the skins of the bananas and potatoes which they had brought

with

them, to be consumed in case of necessity. It was added with a touch

appreciated by those acquainted with Easter Island, that, if the man

who thus

practised foresight was not careful, others who had no food would steal

it when

he was not looking. The

approach of the manu-tara can be heard for miles, for their cry is

their marked

peculiarity, and the noise during nesting is said to be deafening; one

incised

drawing of the bird shows it with open beak, from which a series of

lines

spreads out fanwise, obviously representing the volume of sound; names

in

imitation of these sounds were given to children, such as "Piruru,"

"Wero-wero," "Ka-ara-ara." It is worth noting that the

coming of the tara inaugurates the deep-sea fishing season; till their

arrival

all fish living in twenty or thirty fathoms were considered poisonous.

The

birds on first alighting tarried only a short time; immediately on

their

departure the hopu rushed out to find the egg, or, according to another

account, the rushing out of the hopu frightened away the birds. The

gods

intervened in the hunt, so that the man who was not destined to win

went past

the egg even when it lay right in his path. The first finder rushed up

to the

highest point of the islet, calling to his employer by his new name,

“Shave

your head, you have got the egg." The cry was taken up by the watchers

in

the cave on the mainland, and the fortunate victor, beside himself with

joy,

proceeded to shave his head and paint it red, while the losers showed

their

grief by cutting themselves with mataa. The

defeated hopu started at once to swim from the island to the shore,

while the

winner, who was obliged to fast while the egg was in his possession,

put it in

a little basket, and, going down to the landing-rock, dipped it into

the sea.

One meaning of the word hopu is "wash." He then tied the basket round

his forehead and was able to swim quickly, as the gods were with him.

At this

stage sometimes accidents occurred, for if the sea was rough, an

unlucky

swimmer might be dashed on the rocks and killed. In one instance, it

was said,

only one man escaped with his life, owing, as he reported, to his

having been

warned by Maké-maké not to make the attempt. When the hopu arrived on

the

mainland, he handed over the egg to his employer, and a

tangata-rongo-rongo

tied round the arm which had taken it a fragment of red tapa and also a

piece

of the tree known as "ngau-ngau," reciting meanwhile the appropriate

words. The finding was announced by a fire being lit on the landward

side of

the summit of Rano Kao on one of two sites, according to whether the Ao

came

from the west or east side of the island. It will be remembered that on the rocks which terminate the settlement of Orongo the most numerous of the carvings is the figure of a man with the head of a bird: it is in a crouching attitude with the hands held up, and is carved at every size and angle according to the surface of the rock (fig. 110). It can still be counted one hundred and eleven times, and many specimens must have disappeared: all knowledge of its meaning is lost. The figure may have represented one of the egg gods, but it seems more probable that each one was a memorial to a birdman; and this presumption is strengthened by the fact that in at least three of the carvings the hand is holding an egg (fig. 112). The history of another figure, a small design which is also very frequent, still survives and corroborates this by analogy; within living memory it was the custom for women of the island to come up here and be immortalised by having one of these small figures ("Ko Mari") cut on the rock by a professional expert. We know, therefore, that conventional forms were used as memorials of certain definite persons.15  FIG. 110 — A ROCK AT ORONGO CARVED WITH FIGURES OF BIRD MEN.  [Pitt Rivers Mus.] FIG. 111 — BOUNDARY STATUE FROM MOTU NUI [Measure shown = 1 ft.]  [Brit. Mus.] FIG. 112 — STONE EXHUMED AT ORONGO, 1914. Bird-man in low relief with egg in hand. length of carving, 36.5 cm. The

bird-man, having obtained the egg, took it in his hand palm upwards,

resting it

on a piece of tapa, and danced with a rejoicing company down the slope

of Rano

Kao and along the south coast, a procedure which is known as "haka

epa," or "make shelf," from the position of the hand with regard

to the egg. If, however, the winner belonged to the western clans, he

generally

went to Anakena for the next stage, very possibly because, as was

explained, he

was afraid to go to Hotu Iti; some victors also went to special houses

in their

own district, otherwise the company went along the southern shore till

they

reached Rano Raraku. Amongst

the statues standing on its exterior slope, there is shown at the

south-west

comer the foundations of a house (no. 7, fig. 60). This is the point

which

would first be approached from the southern coast, and here the

bird-man

remained for a year, five months of which were spent in strict taboo.

The egg,

which was still kept on tapa, was hung up inside the house and blown on

the

third day, a morsel of tapa being put inside. The

victor did not wash, and spent his time in "sleeping all day, only

coming

out to sit in the shade." His correct head-dress was a crown made of

human

hair; it was known as "hau oho," and if it was not worn the aku-aku

would be angry. The house was divided into two, the other half being

occupied

by a man who was called an ivi-atua, but was of an inferior type to the

one

gifted with prophecy, and apparently merely a poor relation of the

hero; there

were two cooking-places, as even he might not share that of the

bird-man. Food

was brought as gifts, especially the first sugar-cane, and these

offerings seem

to have been the sole practical advantage of victory; those who did not

contribute were apt to have their houses burnt. The birdman's wife came

to

Raraku, but dwelt apart, as for the first five months she could not

enter her

husband's house, nor he hers, on pain of death. A few yards below the

bird-man's house is the ahu alluded to on p. 191 (fig. 60); it consists

merely

of a low rough wall built into the mountain, the ground above it being

levelled

and paved. It was reserved for the burial of bird-men; they were the

uncanny

persons whose ghosts might do unpleasant things — they were safer

hidden under

stones. The name Orohie is given to the whole of this comer of the

mountain,

with its houses, its ahu, and its statues. To this point the figures

led which

were round the base of the hill. If they were re-erected, they would

stand with

their backs not to the mountain, but to Orohie.16 As the

bird-man

gazed lazily forth from the shade of his house, above him were the

quarries

with their unfinished work, below him were the bones of his dead

predecessors,

while on every hand giant images stood for ever in stolid calm. It is

difficult

to escape from the question. Were the statues on the mountain those of

bird-men? The ho pu

also retired into private life; if he were of the Ao, he could come to

Orohie,

but he might, if he wished, reside in his own house, which was in that

case

divided by a partition through which food was passed; it might not be

eaten

with his right hand, as that had taken the egg. His wife and children

were also

kept in seclusion and forbidden to associate with others. The new

Ao had meanwhile taken up their abode at Mataveri. From here a few

weeks after

their arrival they went formally to Motu Nui to obtain the young

manu-tara,

known from their cry as "piu." After the brief visit of the birds

when the first egg was laid, they absented themselves from the islet

for a

period varyingly reported as from three days to a month. On their

return they

laid plentifully, and, as soon as the nestlings were hatched, the men

of the celebrating

clan carried them to the mainland, swimming with them in baskets bound

round

the forehead after the manner of the first egg. They were then taken in

procession round the island, or, according to another account, only as

far as

Orohie. It was not until the piu had been obtained that it was

permissible to

eat the eggs, and they were then consumed by the subservient clans

only, not by

the Ao. The first two or three eggs, it was explained, were "given to

God";

to eat them would prove fatal. Some of the young manu tara were kept in

confinement till they were full grown, when a piece of red tapa was

tied round

the wing and leg, and they were told, “Kaho ki te hiva," "Go to the

world outside." There was no objection to eating the young birds. The

tara

departed from Motu Nui about March, but a few stragglers remained; we

saw one

bird and obtained eggs at the beginning of July, but the natives failed

to get

any for us in August. When in the following spring the new bird-man had

achieved his egg, he brought it to Orohie and was given the old one,

which he

buried in a gourd in a cranny of Rano Raraku; sometimes, however, it

was thrown

into the sea, or kept and buried with its original owner. The new man

then took

the place of his predecessor, who returned to ordinary life. The last

year that the Ao went to Orongo, which is known as "Rokunga," appears

to have been 1866 or 1867. The names of twelve subsequent years are

given,

during which the competition for the egg continued, and it was still

taken to

be interred at Raraku. The cult thus survived in a mutilated form the